Corruption in Uganda

By Jared Saxton

Published Spring 2022

Special thanks to Robyn Mortensen for editing and research contributions

Summary+

Corruption in Uganda accounts for 1/5 of government expenditure and mainly benefits the rich and well-connected. Due to weak and unspecific laws, corruption is often not enforced in the nation. Additionally, when there are adequate laws in place, enforcement agencies often benefit from corruption and are therefore unmotivated to take action against it. Cultural factors mean that corruption is socially acceptable in many cases and is common throughout the nation. Foreign aid props up corrupt government expenditure because funding comes from an external source, and thus, the government feels less accountable to its citizens. Corruption results in poor service delivery because money is diverted away from important institutions such as hospitals and schools. It also results in hindered economic growth because it keeps firms from being able to compete fairly in markets. Additionally, corruption diminishes trust between the government and its citizens because it undermines the rule of law. While corruption is a continuing issue in Uganda, there are organizations that combat corruption and strategies that have been effective in curbing corruption levels.

Key Takeaways+

- Corruption in Uganda is mainly caused by a skewed power dynamic, allowing those in power to continue to redirect cash flows unhindered.

- Misuse of public funds accounts for as much as 20% of Uganda’s government revenue.

- Because enforcement agencies such as the police and judiciary are some of the most corrupt in the nation, corruption often goes unpunished.

- Economic development is stifled by political corruption as money intended for development and investment purposes is redirected for private consumption.

- Transparency campaigns seek to improve the availability of information and have been shown to have positive effects by lowering levels of corruption.

Key Terms+

Bribes—The illegitimate allocation of funds with the intent to persuade someone to act a certain way.

Embezzlement—The theft of funds that are placed in one’s trust.

IGG/IG—Inspector General of the Government in Uganda tasked with investigating corruption issues within the government itself.

Money Laundering—Generating income through illegal or illicit activities.

NRM/National Resistance Movement—The political party currently in power in Uganda since 1986.

Nepotism—The practice of those in power favoring family and relatives by giving them jobs.

Patronage—The practice of those in power rewarding friends or family in exchange for support.

Political Corruption—Any misuse of power by government officials for illegitimate personal gain.

Public Procurement—The purchase of public resources by the state.

Regime—A specific political group and its allies.

Rent-Seeking—Any attempt to manipulate policy in order to extract personal economic gain, especially to increase the profits of a firm.

Tax Rebates—Discounted taxes often conditional on meeting specific requirements. In the case of corruption, often for political favors.

Transparency Campaigns—Operations carried out with the purpose of making information more publicly available. Also referred to as information campaigns.

Context

Q: What does corruption look like in Uganda?

A: For the purposes of this brief, corruption refers to actions such as briberyThe illegitimate allocation of funds with the intent to persuade someone to act a certain way., embezzlementThe theft of funds that are placed in one’s trust., rent-seekingAny attempt to manipulate policy in order to extract personal economic gain, especially to increase the profits of a firm., nepotismThe practice of those in power favoring family and relatives by giving them jobs., and other illicit cash flows, all of which are common forms of corruption in Uganda.1 Corruption in Uganda and throughout the world is mainly motivated by a desire of the powerful to maintain power and profit monetarily or politically from corrupt transactions.2 Thus, individuals who hold government positions are often those who have the means to engage in corruption. For instance, in 2005 and 2006, political candidates from the National Resistance Movement (NRMThe National Resistance Movement. The political party currently in power in Uganda since 1986.) used money from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria to finance their political campaigns.3 Actions like these, and others including embezzlement, rent-seeking, and bribery, are evident at all government levels.4, 5, 6, 7, 8

Uganda’s leaders are not the only people who engage in corruption. Common citizens also sometimes collaborate with government officials in corrupt actions.9 For instance, in 2017, Transparency International, an organization that fights corruption across the globe, asked Ugandan citizens about the frequency that they encountered bribe solicitations or initiated bribery themselves when they required service from a Ugandan institution. At educational institutions, Ugandans encountered bribesThe illegitimate allocation of funds with the intent to persuade someone to act a certain way. 22% of the time, but with the police, they encountered bribery 67% of the time. Respondents also indicated that they paid the bribes 5.7% of the time at educational institutions and 39.5% of the time while with the police.10 Additionally, 75% of respondents indicated that they had received money or had heard of others receiving money from political candidates in exchange for their votes in democratic elections.11 Therefore, whether interacting with public institutions or government elections, Ugandan citizens also have opportunities to engage in corruption.

Q: Who is affected?

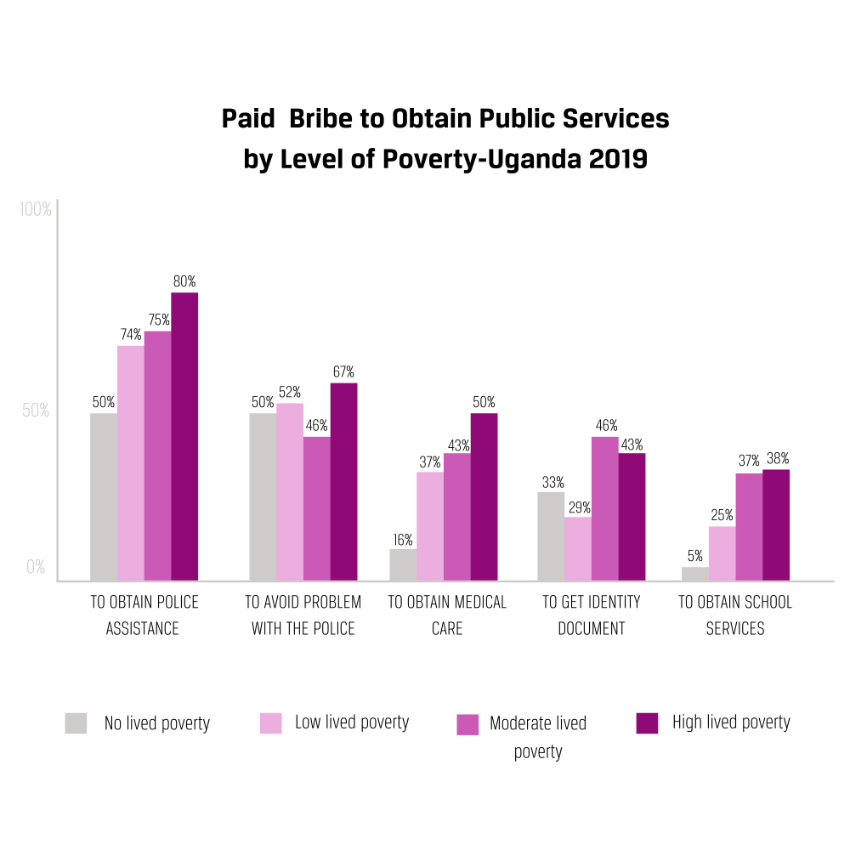

A: Large-scale effects of corruption such as stifled economic growth, poor service delivery, and diminished trust greatly affect Ugandan citizens and businesses.12 Researchers at Makerere University cite ongoing corruption as a large threat to democratic governance and say that it hinders continued development in the nation.13 While these effects are felt at all levels of Ugandan society, corruption has been shown to particularly affect those with low income.14, 15 As of 2020, roughly 25% of the Ugandan population lived below the international poverty line of $1.90 a day.16 Corruption’s disproportionate effect on Uganda’s poor is evidenced because those individuals with the highest poverty levels are those who are most likely to need to pay a bribe to get access to healthcare, obtain school services, and interact with the police.17

Photo by Antoine Plüss on Unsplash

Corruption affects those of low income because corrupt redirection of cash flows away from hospitals and schools underfunds and restricts access to healthcare and education for the poor.18, 19 Furthermore, paying bribesThe illegitimate allocation of funds with the intent to persuade someone to act a certain way. to local authorities or institutions is more burdensome to citizens with less income because paying bribes in order to access local services presents a large financial burden.20, 21 Afrobarometer also states that the percentage of people who report that corruption has worsened in Uganda is higher for other demographics.22 Political opponents of the National Resistance Movement (NRMThe National Resistance Movement. The political party currently in power in Uganda since 1986.) report worsening corruption by 24% more than supporters of the NRM. Those who live in urban areas report worsening corruption 7% more than those in rural areas, and those who live in the central region of Uganda report worsening corruption 4% more than the next highest reporting region. However, whether this means these groups are more affected by corruption is unclear from Afrobarometer’s report.23 Thus, while widespread corruption affects many people in Uganda, it is clear that the poor feel the consequences more acutely.

Q: How is corruption measured in Uganda?

A: Because people who participate in corruption deliberately hide it, corruption often goes unreported, making it difficult to measure.24 For this reason, corruption is often measured by gauging the local people’s perceptions of corruption through questionnaires.25 The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) by Transparency International is the most widely used global corruption measure giving a nation a score from 1 to 100, with higher scores indicating less corruption.26 The CPI for a country is calculated by using questionnaires and data from organizations, such as the World Bank, that are designed to assess public perceptions of corrupt activities.27 The activities that determine the CPI include bribery, diversion of public funds, immunity of public officials, the effectiveness of anti-corruption enforcement, nepotismThe practice of those in power favoring family and relatives by giving them jobs., and public accessibility of information.28

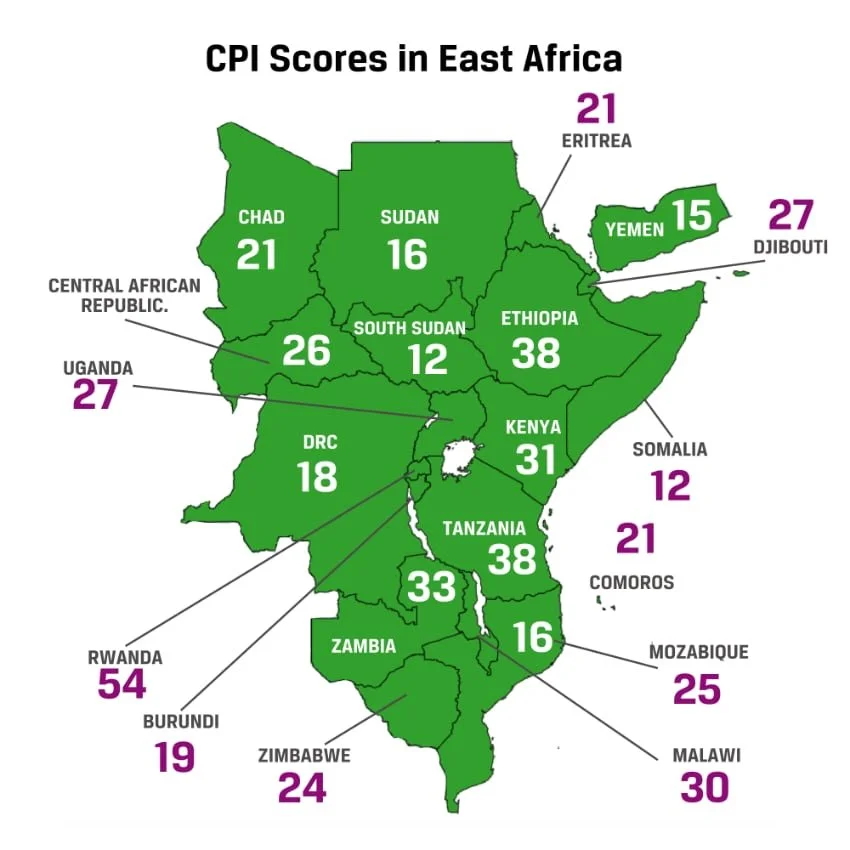

While it is not uncommon for corruption to exist in developing nations, Uganda ranked 142 out of 180 countries on the Corruption Perceptions Index in 2020, with a score of 27.29 Their score puts Uganda below the average for Africa at 32.1 and the world average of 43.2.30 This is not only true for the year 2020; Uganda is regularly ranked as one of the most corrupt countries in Africa and has scored below the world average since at least 2010.31, 32, 33 Additionally, the World Bank ranked Uganda in the 15th percentile for controlling corruption compared to other nations.34, 35 Thus, while it is difficult to directly measure corruption, the available methodologies make it clear that corruption is a problem in Uganda.36

In addition to these measures, Transparency International regularly publishes a report that focuses on a specific type of corruption in Uganda—bribery. This report, called the East African Bribery Index, contains information on bribesThe illegitimate allocation of funds with the intent to persuade someone to act a certain way., including the average size of a bribe and which institutions receive the most bribes. Based on this data, Transparency International reported that 59% of Ugandans believed corruption is growing worse.37

Q: What is the history of corruption in Uganda?

A: Uganda has a long history of corruption that extends back to colonial times and continues into the present. Uganda became a British protectorate in 1894. Under British rule, institutions such as the police, judiciary, and army were established to protect British interests and intimidate indigenous peoples.38 Such intimidation suppressed the people’s courage to oppose their leaders, which fostered the development of a system where leaders were not held accountable by the people for their decisions.39 This system influenced future ideas about corruption, which scholars argue contributes to today’s high levels of corruption.40 In 1962, Uganda became independent from British rule and established its own electoral processes. Under the first post-independence Uganda government, called the Uganda People’s Congress, high-level corruption in government was limited. During this period, government officials were “reputed for their integrity” and made choices that helped to decrease corruption within the country. The research portrays the leaders as inherently moral but provides no other explanation for their integrity, making the reason for the officials’ honesty unclear.41 In 1971, increasing authoritarianism led to a military coup which forced a change of national leadership and resulted in the spread of corruption as a means for the leaders to maintain power.42 Corruption remained a problem through successive changes in leadership in the following years.43

The National Resistance Movement (NRMThe National Resistance Movement. The political party currently in power in Uganda since 1986.) came to power in 1986 through the National Resistance Army (NRA) led by Yoweri Museveni, the current president of Uganda.44 The NRM sought to create legislative reforms in order to curb systemic corruption.45, 46 Although the NRM initially stated that eliminating corruption was one of its top priorities, in subsequent years and into the present, corruption remains an issue. In fact, many members of the party have been involved in corruption scandals themselves.47 This includes former Vice President Gilbert Bukenya, who was accused of stealing money in a transportation deal he made in a Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in 2007.48, 49 As history demonstrates, corruption has developed into a contemporary social issue, and the fact that corruption has not been curbed by the NRM shows that corruption has allowed the party to remain in power over the past four decades.50

Contributing Factors

Inadequate Government Action

Weak Legislation

While some anti-corruption legislation has been passed in Uganda, weak legislation contributes to the prevalence of corruption because the laws are not specific enough and do not present harsh enough consequences for those who break them. Laws such as the Anti-Corruption Act of 2009 seek to dissuade corruption by charging fines and prescribing jail time to those who engage in corrupt practices.51 This law also puts well-defined caps on the amount of money that can be fined.52 Fines for embezzlementThe theft of funds that are placed in one’s trust. in this law are capped at roughly $1,900.00, and fines for false accounting or manipulating financial accounts are capped at roughly $400.00.53 While it is difficult to track exactly how these laws affect the amount of corruption that is actually occurring, researchers believe that these caps do not effectively dissuade individuals from practicing corruption.54, 55 In fact, explicit caps on fines may incentivize government officials to increase the amount of money they are stealing.56 John Muwanga, a previous Ugandan Auditor General who was in charge of monitoring the use of public funds in Uganda, stated in 2013 that when a public official is considering stealing public funds, they will ask themselves, “‘Will it pay?’ If it will, one will steal. If it won’t pay, one won’t steal. It should be too expensive to steal. This is why corruption is happening on a grand scale. They must steal enough to stay out of jail.”57 Here, Muwanga shows that in Uganda, corruption is often a game of calculation.58 If a public official steals more money than they can legally be fined by a court, the perpetrator will be able to pay the fine and still make money.59, 60 Thus, caps on anti-corruption legislation signal to government officials that they should embezzle more money and fail to dissuade them from participating in corruption.

Another problem with current legislation is that anti-corruption fines have not adjusted despite inflation which lowers the value of money. Therefore, when government officials privately consider the risks of participating in corruption, minimum and maximum fines in Ugandan laws are too low with respect to the magnitude of the crime.61 Since 2009, Ugandan inflation has never been below 2% and in 2011 was above 15%. Thus, fines in the Anti-Corruption Act of 2009 have lost between roughly 2–15% of their value each year since the law was passed.62 Therefore, because of inflation, punishments in these laws have been weakened.

Another example of weak legislation that contributes to corruption is ambiguity in mining legislation. For instance, laws do not make it clear whether extreme favoritism in granting government contracts is technically considered illegal.63 A popular Ugandan singer, Jimmy Katumba, used his political connections to obtain mining contracts and sell them for profit.64 Researchers argue that if an action is not clearly defined as illegal, it will likely not be prosecuted, as in Katumba’s case.65 Furthermore, other legal provisions scattered throughout mining legislation, including unchecked power by government authorities and lack of regulation of small-scale miners, create an atmosphere where individuals are more likely to engage in corruption.66

While weak legislation contributes to corruption, some scholars have noted that the anti-corruption legal framework is fairly well-developed in Uganda.67, 68, 69, 70 This is because, compared to other nations, Uganda has set up some agencies that have the potential to combat corruption effectively. For instance, the Inspector General of Government (IGGInspector General of the Government in Uganda tasked with investigating corruption issues within the government itself.) is a government position created to investigate corruption in government. In addition to the IGG, Uganda also has an office of Auditor General who is tasked with checking whether public funds have been used effectively, and the Directorate of Ethics and Integrity is an institution charged with combating corruption across the nation.71, 72 So while specific laws and provisions, such as fines and punishments, are not effective at reducing levels of corruption, the Ugandan government has taken steps to limit corruption.

Enforcement

Scholars who say Uganda’s anti-corruption framework is well-developed credit bad enforcement and lack of political will as the reasons why legal provisions have not been effective.73, 74 Uganda has one of the largest implementation gaps when compared to other world nations.75 An implementation gap is a metric used for measuring the difference between what legislation prescribes and the actual enforcement of that action.76 One reason for this lack of enforcement is that the individuals who hold power to punish corruption are the same ones who benefit most from allowing corrupt practices to continue.77, 78 While there are provisions for punishing corruption, corruption perpetuates because those in power do not enforce the legislation.

The President of Uganda

One prominent example of the lack of enforcement is the case of the presidency. President Museveni, the President of Uganda since 1986, has been accused of letting corruption become a mechanism whereby he can remain in power.79, 80 He has created support among powerful individuals by allowing them to misuse public funds or misusing them himself.81, 82, 83 Some of these individuals include military officers who supported his campaign financially in 2001 and helped him win the election.84 Others are members of parliament; in order to change the law and lift limits on presidential terms in 2004, Museveni offered payments to members of parliament of $4,500.00 to “facilitate” political support.85 Museveni has also created support among some businessmen. For example, In 2004, Museveni ordered the Bank of Uganda to pay $11.5 million to a wealthy businessman, Hassan Bassajabalaba, who in return helped to mobilize support for lifting term limits on the presidency.86 This change allows Museveni to remain in power to this day.87 Museveni also has consolidated support through nepotismThe practice of those in power favoring family and relatives by giving them jobs. by appointing family members to top positions in government. He has appointed his wife as minister of state in Karamoja, his brother as Senior Presidential Advisor, his brother-in-law as minister of foreign affairs, his son as commander of the Special Forces, and his daughter as a private presidential secretary.88 Despite this evidence, Museveni claims that he has never been involved in any form of corruption.89 Although, as the president of the nation, he holds power to mobilize enforcement agencies to stop corruption, Museveni allows corruption to occur and engages in it himself because it has become a method whereby he maintains political support.

Inspector General of Government of Uganda (IGG)

Another example of the lack of enforcement of anti-corruption measures is the case of the Inspector General of Government of Uganda (IGGInspector General of the Government in Uganda tasked with investigating corruption issues within the government itself.). The position of the IGG was created in 1988 to oversee accountability in government, including the detection and prevention of corruption.90 The position also has the power to prosecute high-level government officials in addition to making investigations and reports.91 However, the position is known to investigate mainly low-level cases of corruption in local governments or schools.92 The IGG does not publish the number of complaints that are made to high-level government officials, but in the first 6 months of 2020, the IGG office sanctioned 341 of 669 complaints of corruption and maladministration to be investigated. However, only 23 prosecution cases were closed, and only 8 arrests occurred during that period, and none of the arrests were for high-level government officials.93 Among the arrests were a primary school teacher, a secondary school teacher, and a university secretary.94 Because there are seldom arrests of prominent government officials, the public files fewer corruption reports over time, suggesting that Ugandans do not believe the IGG will take action.95, 96

One reason behind the lack of high-level action by the IGGInspector General of the Government in Uganda tasked with investigating corruption issues within the government itself. is that the position is not sufficiently disconnected from the executive arm of government as the IGG is directly appointed by the president. Jotham Tumwesigye, a former IGG from 1996 to 2004, was a prominent member of the NRMThe National Resistance Movement. The political party currently in power in Uganda since 1986. before he was appointed to be IGG. He attended meetings of the NRM National Conference while he held the position, undermining his impartiality.97, 98 While the position is supposed to be accountable to parliament, taking any action that might go against the will of the current president would risk the IGG losing their position in power. This is evidenced by the fact that one of the former IGGs, Wasswa Lule, was fired by Museveni in 1992 for publishing the names of corrupt officials that the president did not want to be investigated.99, 100, 101 In this way, the motivation of the executive branch of government is closely tied with the motivation of the IGGInspector General of the Government in Uganda tasked with investigating corruption issues within the government itself., and any anti-corruption enforcement that the IGG could take against the executive branch may be ignored. The position has also been used to deflect attention away from high-level individuals by prosecuting scapegoats.102 In these cases, the IGG not only ineffectively deals with high-level corruption but becomes another pawn wherewith the current regimeA specific political group and its allies. perpetuates its own immunity from anti-corruption enforcement.

Other Government Institutions

Other reasons for a large implementation gap come from corruption within enforcement agencies such as the police and judiciary.103 Both institutions are in charge of enforcing much of the anti-corruption legislation in Uganda but are also some of the most corrupt institutions in the nation.104 The East Africa Bribery Index shows that bribery was asked or offered in 67% of interactions between the judiciary and private citizens and in 66% of interactions between the police and private citizens.105 This creates a situation in Uganda where those who are responsible for combating corruption are the same people who are most engaged in it; thus, very little enforcement actually takes place, as evidenced by continued high levels of corruption.106

Furthermore, some enforcement agencies do not possess the necessary resources or information to enforce Ugandan laws. One example of this is in the case of the Financial Intelligence Authority, the government institution in charge of investigating money launderingGenerating income through illegal or illicit activities. in Uganda and enforcing anti-money laundering laws.107 Despite the fact that Uganda has been recognized internationally as a nation with money laundering problems, the government of Uganda has not allotted enough money to the Financial Intelligence Authority to help solve the issue.108 In a 2022 interview, the Executive Director of the Financial Intelligence Authority stated that the head office only employs 43 people due to budget shortages, even though the recommended amount is 83.109 Additionally, they do not have the necessary technology to track money effectively, and, therefore, Uganda loses over $1 billion every year from money laundering and corruption.110 The director stated that the Financial Intelligence Authority needs an additional $9 million from the government to cover these deficiencies in staff and technology, but so far, the request remains unmet.111 Even with more money, however, the institution would still lack relevant skills and experience to be effective.112 Thus, the Financial Intelligence Authority lacks the capacity to curb money launderingGenerating income through illegal or illicit activities. because it does not possess the necessary funds, technology, staff, or skills to convict individuals on money laundering charges.113, 114

Normalization of Corruption

Perpetual, widespread corruption in all levels of government has normalized corrupt practices to a large degree in Uganda.115 In Uganda, close social networks are very important to individuals as direct family and close friends can provide a safety net to citizens and may help to provide for basic needs. Additionally, in 2017 researchers at the Basel Institute on Governance reported that for citizens, loyalty to one’s social network is often seen as more important than obedience to Ugandan laws.116 Because of this, corruption is socially acceptable if it is used as a means to help one’s social network or reciprocate a favor.117 Further evidence from personal interviews suggests that the public does not view stealing government money in Uganda as the selfish enrichment of an individual but for the collective benefit of their family and friends.118 For this reason, a retired public official (who chooses to remain anonymous) said that family and friends encouraged him to practice corruption when he was in office and that other officials expected money in exchange for political favors.119 Another respondent stated that public officials were looked down on if they were seen as poor.120 Evidence suggests this is because the obligation to take care and provide for your family is an “essential and unquestionable premise of social life in [Uganda],” and if they are poor, they are seen as unable to provide.121 Thus misuse of public funds is not only socially acceptable but public officials are sometimes encouraged to steal money so they can appear wealthier and fall in line with the public’s expectations.

Photo by Social Income on Unsplash

Additionally, some interviewees stated that the government could easily be seen as something impersonal and abstract, not as an individual or group of people. This causes theft of government funds to appear like a victimless crime to some Ugandans and therefore be considered not very serious.122 One interviewee said that communities do not know how to react when someone steals from the government because it is not tangible like an individual, and thus the perpetrator is not always punished.123 Therefore, because the Ugandan people do not perceive the theft of public funds as criminal, corruption continues unpunished. Other evidence from interviews builds upon this idea by suggesting that labeling political favors and patronageThe practice of those in power rewarding friends or family in exchange for support. as corruption is an alien concept to some Ugandans and that it is seen as an overtly ‘western’ way of thinking about the allocation of state resources. Therefore, actions that westerners may classify as corrupt may not even be perceived by all as a bad thing in Uganda; thus, they continue virtually unhindered.124

The same interviewees also provide evidence that Ugandan elected officials are sometimes seen as providers of government services that they are not legally responsible for.125 This means that local government candidates will make outrageous promises to the public in order to get elected and then be forced to steal money in order to actually provide the promised services to their constituents.126 Some of these exaggerated promises include helping constituents with school expenses, funeral expenses, and funds for religious facilities.127 This norm is not helped by the fact that the current president himself has defended his own questionable actions of awarding government contracts to gain influence, arguing that by doing so, he has protected the public interest.128

Interviews done in Uganda further suggest that both local election candidates and constituents view their relationship with each other as exploitative, meaning that they are only interested in what they can get out of the other.129 While it is natural for constituents to vote in elections based on what they expect to receive from candidates, sometimes Ugandan citizens will vote depending on which candidate can buy their vote. In a survey conducted in Uganda, 75% of respondents indicated that they had received money or had heard of others receiving money from political candidates in exchange for their votes in democratic elections.130 Candidates will sometimes use personal resources to finance such bribesThe illegitimate allocation of funds with the intent to persuade someone to act a certain way.. In this way, not only is the electoral process corrupt, but once candidates get elected to office, they use their position to embezzleThe theft of funds that are placed in one’s trust. funds and recover what was lost in bribe payments.131

The Ugandan people do not unanimously agree that corruption is socially acceptable in all cases. While many individuals expressed the opinion that corrupt practices can be socially acceptable, practices such as extortive bribery are condemned by many as well.132

Foreign Aid

The international community, despite good intentions, has not always helped corruption in Uganda. In fact, evidence shows that measures taken by the international community have instead contributed to the practice through large amounts of unregulated foreign aid, donor funds, and debt relief. Foreign aid and donor funds are monies given to the Ugandan government from other state governments or from private institutions to help fund education, poverty reduction, healthcare, and infrastructure in the nation.133 Foreign aid is so important to Uganda that in 2006, it made up around 50% of the total government budget.134 However, because aid makes up such a large amount of state resources, it also limits the government’s accountability to the Ugandan people. This was illustrated when aid doubled in 2005, and the Ugandan government increased its public administration budget to $120 million—a budget that is known to be a large source of political patronageThe practice of those in power rewarding friends or family in exchange for support. money.135 Instead of using the money on projects that might benefit the Ugandan people, the government chose to put the money toward “public administration,” where at least a portion of it would be used in bribesThe illegitimate allocation of funds with the intent to persuade someone to act a certain way..136 Thus, when revenue that comes from honest taxation of the people makes up a smaller fraction of the government’s expenditure, Ugandan officials are more likely to engage in corruption because they are not accountable for those funds to the Ugandan people.137

In the 1990s, large donors such as the United States and the United Kingdom focused mainly on economic reform in Uganda and largely ignored governance because they wanted to support economic growth.138 Because donors did not monitor the use of their funds, government officials could use the money irresponsibly with little accountability, although whether the Ugandan government purposely limited monitoring or donors failed to follow up is unclear.139 Thus donor aid relies largely on the willpower of the Ugandan government to operate successfully. Even when evidence of corruption came to light, foreign aid continued to pour in, fueling a culture of high-level corruption and impunity.140 Because the process of foreign aid relies on donors’ trust in the government, the NRMThe National Resistance Movement. The political party currently in power in Uganda since 1986. has been able to misappropriate foreign aid money while maintaining the outward appearance of pursuing an anti-corruption agenda.141 In 2019, President Museveni led a march against corruption in Uganda and was later criticized because his government was to blame for much of it.142 While there have been criticisms by donors and other governments about the misuse of aid funds, foreign aid has continued to increase to $2.1 billion in 2019, up from just $855 million in 2000.143, 144 Threats from Denmark and the United States in 2007 to cut aid have not been carried out.145 Some nations, notably Italy and Norway, have reduced aid, but major funders have not stopped the flow of money for fear that their economic and political agenda in Uganda will be undermined.146 For instance, some claim that Ugandan military forces helped smuggle weapons into Sudan and that they continue to help combat militants in Somalia, both of which are consistent with the US political agenda.147 While, in some cases, donor funds are being scrutinized and withheld if the Ugandan government does not use them correctly, foreign aid has largely continued to prop up corruption in Uganda.

Researchers claim that the misappropriation of government resources in Uganda today is still supported by foreign aid.148 One extreme example of this is that the government has been able to maintain thousands of ghost soldiers on the government’s payroll because foreign aid provides the necessary funds. This means that soldiers who have either died or simply never existed are being paid, but have their salaries go to corrupt government employees. In practice, these monies are largely redirected into the pockets of high-ranking military and state officials instead of helping further economic or anti-corruption reform.149 This is done because military expenditure is outside the scope of relevant international regulations and, as a result, is easier to use for corrupt expenditure in Uganda.150

While there is now some scrutiny with regard to the use of donor funds, foreign aid still perpetuates corrupt practices in Uganda.

Negative Consequences

Poor Service Delivery

Corruption in government unnecessarily diverts government funds away from their intended purpose. In Uganda, estimates suggest that between 10–20% of government revenue is misused.151 Because government funding in Uganda helps to provide a number of important services to the public, such as healthcare, education, and aid programs to the poor, diverting funding away from these areas means that service delivery in such areas suffers.152 Thus, not as many people are able to get access to these services, and the services are lower quality when obtained.153

Photo by bill wegener on Unsplash

As the Ugandan government intentionally disrupts cash flows, programs that rely on government revenue become underfunded. This means government programs such as social programs, development programs, and education do not function at the same capacity as they would have if they were fully funded.154 In Uganda, there is evidence of redirected cash flows, such as when money was anonymously stolen from a fund to fight tuberculosis, AIDS, and Malaria and to provide vaccinations to children in Uganda in 2005 and 2006.155, 156 Additionally, in 2012 and 2013, there were claims that government staff funneled over $12 million from aid programs into private bank accounts and misappropriated around $24.5 million meant for post-conflict reconstruction projects, thus diverting funds that were needed in their respective programs.157 In outrage at this, some donors cut aid money which hurt both the intended recipients of the money and other government programs such as the ministry of health and the ministry of finance that are important for development in Uganda.158

Bribery, in particular, can act as a barrier to citizens having access to important government services. The East African Bribery Index shows that 54% of citizens believed that bribery was the only way to access services they were looking for, including services from the police and judiciary.159 Since these legal institutions are largely utilized only through corruption, it discourages citizens who might need such services from seeking them out. Additionally, in a survey done by Afrobarometer, 42% of respondents indicated that they had to pay bribesThe illegitimate allocation of funds with the intent to persuade someone to act a certain way. to access medical care, raising concerns that corruption significantly bars access to healthcare in Uganda.160 Forty-two percent of Ugandans also report that bribes are needed in order to receive birth certificates, driver’s licenses, permits, or other documentation; 26% report bribes are necessary to access services at public schools.161 Because the United Nations defines education as a basic human right, the fact that bribery bars access to it is of particular note.162

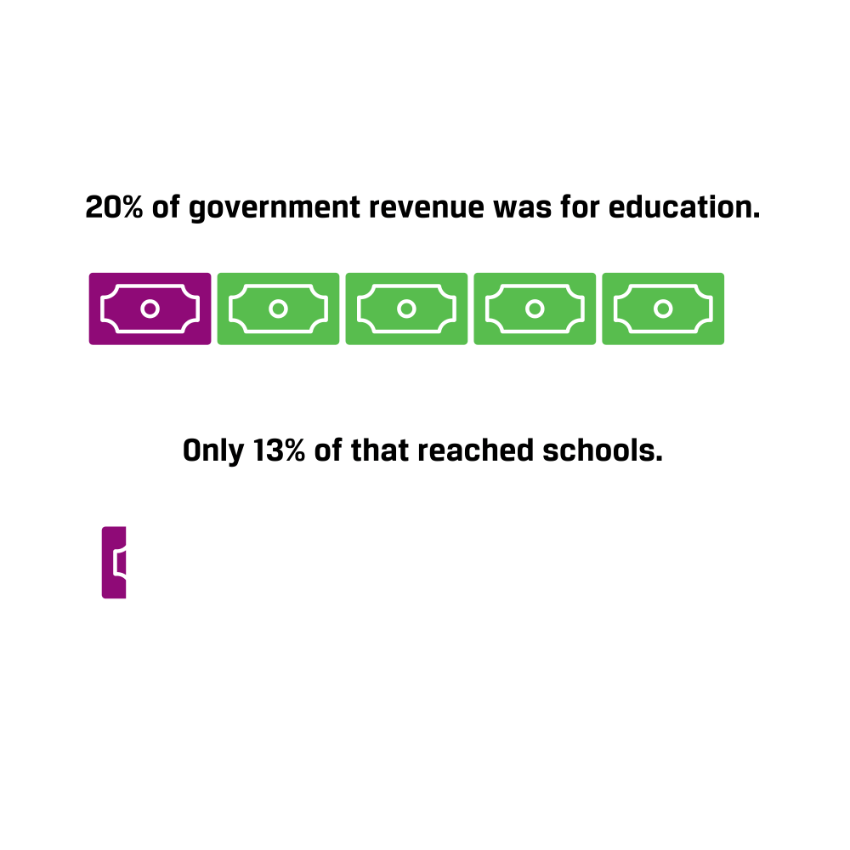

Corruption in Uganda has also been shown to negatively impact Ugandan education. In the 1990s, 20% of Uganda’s government expenditure was seemingly for education, but only 13% of the grants intended for education ever actually reached the schools.163 A large portion of the money disappeared, and—while that fact does not necessarily mean that the money was stolen—the fact that other areas of government had no corresponding increase in spending strongly implies that the funds were simply embezzledThe theft of funds that are placed in one’s trust. by government officials. This resulted in most schools receiving no funding at all.164 Further studies found that when Ugandan schools receive more funding, student enrollment increases. In other words, continued corruption in government diverts funding away from educational programs and keeps Ugandan children out of school.165

Hindered Economic Growth

Corruption in Uganda stifles economic growth because as money is lost, the economy does not operate efficiently.166 Empirical evidence analyzing corruption and development levels across the world shows that corruption is associated with low levels of development, but whether underdevelopment causes corruption or corruption perpetuates underdevelopment is ambiguous in some research.167, 168 Because corruption is especially associated with underdevelopment in countries that experience low government effectiveness and the rule of law—such as Uganda—it implies that corruption indeed causes underdevelopment in these countries.169

In a recent report by the IGGInspector General of the Government in Uganda tasked with investigating corruption issues within the government itself. of Uganda, surveys show that people in Uganda cite increasing and perpetuating poverty as well as underdevelopment as effects of corruption in the government.170 (Because the IGG is closely politically tied with the NRMThe National Resistance Movement. The political party currently in power in Uganda since 1986., this may not be entirely accurate. It is true, however, that since these statistics are not necessarily targeting the NRM, they are likely not tainted with political bias). Ugandan citizens believe that corruption harms the economy because it causes delays in development project implementation and discourages investors from putting money into the country’s economy.171

This underscores evidence from research showing that Ugandan corruption negatively impacts the growth of individual companies; a 1% increase in bribe payments decreases company growth by 3.3%.172 This evidence is consistent with theoretical literature explaining that corruption hinders economic growth because it adds to the cost of participating in economic activity in that nation. These costs include instability, uncertainty, complicating entrepreneurship, diverting talent to illicit activities, and discouraging investment.173, 174 In Uganda specifically, researchers claim that small enterprises are particularly harmed by corruption because they lack social networks, which give large firms a comparative advantage in doing business.175 Corruption keeps companies from growing and sharing profits with citizens, which in turn hinders the efforts of small business owners to escape poverty.

Additionally, corruption can harm the economy by rerouting public funds away from areas that stimulate the economy, such as infrastructure. In Uganda, the national government had stated that oil revenues were to be used for infrastructure and development; however, in 2011, a Ugandan Parliamentary committee found that over $500,000.00 had gone missing in transfers of oil revenue, possibly in the form of bribesThe illegitimate allocation of funds with the intent to persuade someone to act a certain way. to senior government officials.176 The World Bank reports that Ugandan infrastructure is underfunded by roughly $400 million a year, with most of the funds omitted from water, irrigation, and sanitation infrastructure.177 Additional money disappearing from infrastructure budgets can only exacerbate infrastructure problems within the country. Therefore, interrupted cash flows such as this contribute to a weakened Ugandan economy because the money is not used effectively.178

Corruption, by nature, also creates political favoritism, which can lead to economic inefficiencies. For instance, if a company paid bribesThe illegitimate allocation of funds with the intent to persuade someone to act a certain way. in order to secure government contracts, this would violate the natural efficiency of markets because it does not guarantee that the company receiving the contract is the most capable of carrying out the project.179 There is evidence that such political favoritism occurs in Uganda. For instance, in 2008, management of the Jinja oil reserves was given to Heritage Oil—a company with alleged ties to the President.180 There have also been many allegations of bribery and rent-seekingAny attempt to manipulate policy in order to extract personal economic gain, especially to increase the profits of a firm. in the process of contracting companies for the construction of the Karuma hydroelectric dam.181, 182

Trust

Corruption is associated with both low levels of trust between the public and the government and low levels of trust between individuals in a country.183 In Uganda, the majority report that corruption is getting worse, and 73% of Ugandans believe that the government is doing a poor job of combating the problem.184 Furthermore, 77% of Ugandans believe that reporting corruption is ineffective and doing so risks retaliation or other negative consequences.185 Another report states that the public has “no trust” in the office of the president, the Inspectorate of Government, or the police of Uganda.186

Lacking trust in government can be a problem because it has been shown that when there is low trust, people are less likely to use government services. This can be especially detrimental in institutions like criminal justice and the judiciary. When the public doesn’t use these services as intended, it can undermine the authority of such institutions and make them ineffective at performing their respective functions. Additionally, when parents mistrust educational institutions, they may be prompted to pull their children out of school.187 Surveys show that Ugandans perceive high levels of corruption in all these areas.188, 189

Corruption in Uganda affects international trust in the Ugandan government as well. For instance, when the international community found out that Ugandan officials had siphoned over $12 million from aid programs, countries such as Britain, Ireland, Denmark, and Norway suspended aid to the country.190 As a result of the funding cut, the Ugandan government allocated less money to domestic aid and development programs.191 This is consistent with the theoretical model that suggests that corruption creates uncertainty about the honest and well-intentioned use of money, which discourages foreign investors.192 Thus international trust is diminished by corruption.

Best Practices

Transparency International Uganda

Transparency International Uganda (TIU) is an anti-corruption organization that was founded in 1993 to increase transparency and integrity in Uganda. It became an official chapter of Transparency International (TI) in 1996.193 It is also an officially registered NGO in Uganda.194 While the information on funding specific to TIU is unavailable, TI states that 82% of its funding comes from governments and multilateral donors, and the rest is made up of foundations, corporations, and others.195 TI’s policy is not to accept donations from any entity that has engaged in corruption and has not taken measures to stop it.196

TIU’s mission statement is to “promote consciousness about corruption and a society that espouses value systems and principles of transparency and accountability.”197 TIU does this by focusing on three main objectives: promoting transparency and accountability in key socio-economic service delivery sectors, enhancing citizen participation in the governance of natural resources, and strengthening accountability in democratic processes.198 TIU fulfills its objective of transparency and accountability at the national level by partnering with Ugandan ministries and other institutions and seeking change. They work on their objectives of enhancing citizen participation and democratic accountability by helping citizens understand the laws that govern natural resource allocation in Uganda and laws that regulate the electoral process. In practice, this means they lead interventions such as research, awareness campaigns, and capacity building of communities and local governments.199 Often, TIU partners with other organizations for their interventions as well. For instance, in 2018, they reported that they partnered with many organizations, including USAID (a US development agency), CIPESA (an East African communications technology organization), and UMEME (a Ugandan power company).200 They have worked in a variety of districts ranging from the greater Masaka region, Hoima, Buliisa, Moroto, Nakapiripiriti, Lira, Oyam, Apach, Mubende, Nakaseke, Mityana, Nebbi, Ntungamo and Kampala.201 Thus, transparency International Uganda helps to fight corruption with a variety of methods at many levels.

One example of an intervention they took part in is called Land Rights Open Days. In 2016, TIU began this initiative to increase information awareness about land corruption (or corrupt land seizure).202 Land Rights Open Days are community events held in Mukono and Wakiso districts in the Central Region of Uganda, where citizens are provided both information on their land rights and opportunities to access legal services.203 TIU also published a handbook in 2017 called Land and Corruption that provides a summary of laws, norms, and practices for land ownership in Uganda. TIU created the handbook in response to a lack of awareness of these laws with the intent that it helps hold officials accountable for injustices in Ugandan land governance.204 In 2018, TIU also held meetings with Ugandan Chief Justice Bart Katureebe to help promote transparency in the country.205 Furthermore, in 2018 TIU participated in a range of activities such as public procurementThe purchase of public resources by the state. training, paralegal training, social media campaigns, research publications, and 35 talk shows.206

The impact of TIU’s interventions is difficult to assess, although it is generally positive. TIU states in their annual reports what activities they participate in, but they fail to report any change in negative consequences for Ugandan citizens. One source says that because of the Land Rights Open Days intervention, land corruption reported by citizens increased significantly, although the source fails to report by how much.207 Further, a report on an intervention TIU implemented to increase transparency in the health sector simply stated that it helped to bridge a gap between organizations and the Ugandan government. It also reported that information on medical infrastructure spending was disclosed more often and accessed easier due to the intervention but failed to report any quantitative improvement.208 Additionally, it fails to report if the results it does see are permanent changes or if it disappears quickly after TIU shifts focus to other areas or other interventions. If this organization were to collect more data and more specifically evaluate its performance, it might shed light on ways it can improve its interventions. This would help it to more effectively combat corruption in Uganda. Despite this, TIU continues to be an important player as it promotes transparency in the fight against corruption in Uganda.

Preferred Citation: Saxton, Jared. Corruption in Uganda.” Ballard Brief. June 2022. www.ballardbrief.byu.edu.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints