Educational Funding Inequality in Southern US High Schools

Photo by 1a_photography on Istock

By Emma Madeux

Published Winter 2024

Special thanks to Susan May Watts for editing and research contributions

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Summary+

Educational funding budgets and sources vary from state to state, but in the southern United States, inequality in educational funding is a prevalent issue, especially in rural districts. The South’s economy has been historically behind when compared with other regions of the US; the South’s economic issues carry over into school funding and negatively affect students and teachers. Government policies concerning public school funding, systematic racial inequality, and economic inequality in the southern region contribute excessively to the problem of funding inequality. As a result, students in underfunded schools suffer a lack of access to much-needed mental health resources, higher chances of dropping out and developing behavioral issues. The consequences of educational funding inequality have long-term effects on students and the American economy. Changing government policies that determine the way schools are funded could be instrumental in giving every student a chance at a bright future.

Key Takeaways+

- There is little being done to understand and solve the problem of underfunding in rural areas of the US.1

- Per-pupil spending has become an indicator of the success of students in public schools, and disparities in PPS increase when school districts are separated geographically along racial and socioeconomic lines, these disparities in spending increase.2

- The unique, spread-out geography of the region contributes to the lack of access to resources and quality teachers.

- School budgets are increasing, but not at a fast enough rate to match the inflation that is occurring in the US economy.

Key Terms+

Dropout—A student who does not complete their schooling and therefore does not receive a high school diploma.3

Economic Burden of Racism—Loss of human capital (knowledge, skills, experience, and health that people accumulate throughout their lives) as a result of racial disparity.4,5

Emerging Adult—An individual between their late teens and through their twenties, during a period in their life when they have not yet reached the independence and self-sufficiency associated with adulthood.6

Fair Wage—A wage fairly corresponding with the value of the services rendered.7

Racial Disparity—Disproportion in the way racial groups are treated when it comes to income, education, economic status, and so on.8

Redlining—A discriminatory and illegal practice in the United States where a mortgage lender or insurance provider restricts or denies services to certain applicants in certain communities because of the racial characteristics of their neighborhood.9

Stealth Inequities—Qualities of systems to fund schools that heighten inequities in per-pupil spending.10

Context

Q: What is educational funding inequality, and why is it an issue?

A: Educational funding inequality happens when the systems put in place for funding public schools cause wealth disparities in a community to extend to education systems, thus causing school districts in impoverished communities to receive less funding from state and local governments.11 The current system for school funding relies heavily on which tax bracket one lives in; those who live in a higher tax bracket will have more funding.12 While schools in areas with lower tax brackets receive more federal aid than their wealthy counterparts, this additional help does not make up for the remaining 14.1% gap in funding between high and low-poverty school districts.13 Inequality in educational funding is directly related to achievement gaps and opportunity gaps among students in public schools. These gaps have their roots in racial and economic inequality.14

Photo by Ranplett on Istock

One example of an achievement gap is the fact that black and Hispanic students are far less likely to be enrolled in Advanced Placement (AP) classes in high school than white students. Lower grades and test scores limit the likelihood of these students finishing high school and attending college, therefore limiting their options for the future.15,16 This disparity occurs because, across the United States, school districts with the most black, Latino, and native students receive as much as $2,700 less per student in government revenue than predominantly white school districts.17 Without this money, students of color lack the extra resources and support that their white peers in wealthier school districts have inside and outside of school.18

Funding inequality leads to a lack of key resources and quality curriculums needed by students to succeed and be supported in learning both at home and in school.19 These key resources can be defined as a school resource that contributes to the academic progress of students; for example, mental health services. Mental health services vary from school to school but could include psychologists, social workers, guidance counselors, or even a curriculum that incorporates social and emotional learning.20 While students in higher-income regions of the United States use mental health resources outside of their schools, adolescents who come from low-income households or are from a racial or ethnic minority group tend to access these services in an educational setting.21 Higher demand for these services in low-income school districts requires a higher supply which is not being met in rural areas of the country due to underfunding. Schools with little funding do not have the time and resources to develop new and progressive curriculums that contribute to student success and well-being.

Q: Who does educational funding inequality primarily affect?

A: This issue primarily affects public high school students in impoverished school districts because they are on the cusp of adulthood and financial independence, meaning that educational funding inequality directly impacts their future career and economic prospects. These high school students feel pressure to succeed, whether that be from family, teachers, or themselves, but are not given the tools to do so because the financial disparities of their community carry over and affect their education.22,23 The effect of underfunding is divided by geographic, racial, and social lines. Because of systematic inequality issues that the United States still faces, students of color and students from low-income families are greatly affected by issues of underfunding.24 These demographics also tend to be divided geographically, matching similar divisions in underfunding, making the problem greater in regions such as the southern United States, which has higher populations of people of color and those near the poverty line.25,26 Per-pupil spending has become an indicator of the success of students in public schools. Changes in racial or ethnic segregation are associated with disparities in per-pupil spending among racial and ethnic groups. As school districts are separated geographically along racial and socioeconomic lines, these disparities in spending increase.27 Per-pupil spending in many states has decreased since the recession in 2008.28 The divide between states that increased per-pupil funding versus those that decreased shows that most of the Southern United States decreased their per-pupil funding significantly while many of the northern states with already wealthier school districts increased their funding after 2008. Oklahoma, for example, decreased per-pupil spending by over 23%, while North Dakota increased theirs by over 31%.29 Similarly, Alabama decreased spending by 17.8% while Connecticut increased theirs by 9.1%. These are both significant contrasts because they reflect the economic divide between the North and the South. Oklahoma’s median household income is more than $11,000 below North Dakota’s, while Alabama’s is more than $30,000 below Connecticut’s.30,31,32,33 As the wealthy schools get wealthier, students from schools in impoverished districts struggle to catch up because of the economic divide that carries over into public school funding.

Q: How has funding in rural southern US schools changed over time?

A: Every year, certain amounts of money are allocated to state education agencies under the Rural and Low-Income School Program in which the US Department of Education authorizes grant awards to eligible states and helps their school districts use that funding more effectively.34 The educational statistics reported from the years 2004–2013 the amounts allocated annually fluctuated, but on average, as of 2023, there was a downward trend in the amount of funding that was allocated to rural schools.35 In 2006–2007, school year expenditure in rural public schools was reported to be about $13 million on average; with inflation, that number would have been about $17 million in 2019, and yet in the 2018–2019 school year, there was only $15 million in reported expenditures in rural public schools.36,37

Historically, policies such as the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965 and the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) of 2001 drew attention to disparities in educational funding for school districts with low-income and racial minority groups. ESEA was a Civil Rights Act that provided low-income school districts with federal grants.38 NCLB’s objective was to provide funding to low-income public schools and keep them accountable by establishing standards for education and using standardized test scores as an indicator of success. Even though NCLB succeeded in pointing out the achievement gap, it did little to solve it. In fact, they penalized schools that did not meet performance standards by firing staff and sometimes closing the school altogether.39,40 These requirements put in place by NCLB became increasingly impracticable for public schools, and in 2010 the Obama administration began to meet with educators and families to revise the law.41 By 2015, NCLB was dismantled and replaced by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which focuses on preparing students for college and future careers.42,43 Instead of providing federal funds to underfunded schools, ESSA primarily focuses on identifying the problems that are causing the inequity in funding. ESSA identifies problems by requiring schools to report per-pupil spending and conduct needs assessments, and testing a district-level weighted student funding system that will attempt to distribute funds more equitably.44

Q: What are graduation rates in southern US high schools?

A: In this issue brief, the American South will be defined in terms of its history and culture and will include the following fifteen states: Oklahoma, Texas, Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, West Virginia, Virginia, and North and South Carolina.45 Graduation rates in the southern United States are typically lower or comparable to the national average, which is currently about 91%.46 Only 2 of the 15 southern states, Missouri and Virginia, had a graduation rate above 89%. On average, the graduation rate for the 15 southern states was about 88.76%, while the average rate for all other states, excluding those 15, was around 92%.47

Graduation rates in the US are improving on average. In 10 years, from 2002 to 2012, high school graduation rates climbed from 72.6–80%.48,49 Despite the national increase, the gap in graduation rates between the North and the South did not close. In 2002, the difference in graduation rates between the North and the South was about 2.33%, and the gap was around 3.24% in 2023.50,51 With nationwide graduation rates rising, the gap should be closing, but the fact that it is widening illustrates that public school graduation rates in the South are growing at a much slower rate than in the North.

Q: How does underfunding in the rural US differ from underfunding in urban areas?

A: Public schools are funded by federal, state, and local governments. The formula for funding varies from state to state, but on average in the 2019–2020 school year the federal government accounted for 7.6% of funding, the state for 47.5%, and the local government for 44.9%. Typically, about 81% of local funding comes from property taxes.52 Property tax is made up of the basic rate, a local levy that is voted on, and a board levy. There are more resources that are specifically allocated to schools that are in a higher tax bracket because they pay more in property taxes.53 People who live in urban areas tend to pay more in property taxes because of higher infrastructure costs and property values.54 Out of all the school districts in Alabama, the eight highest-funded districts were in urban public school systems, while the eight lowest-funded districts were all in rural public school systems. Interviews and surveys of the school’s staff conducted in this same study further supported these findings.55

The problem of underfunding in rural areas is significant to the South because nearly half of all people in the US living in rural areas live in the South; this is significant when compared with the Western US, which has a larger amount of rural spaces, but only 10% of its population lives in those rural areas.56 The southern region of the United States pays some of the lowest property taxes in the country, with some residents of Alabama and Louisiana paying less than $200 a year.57 The average cost of property taxes in 2023 of the 15 states defined in this brief was $1498.13, while the average property tax in the state of New Jersey, for example, was $8,797.58 The inadequate school budgets in the southern United States adversely affect public school students because their schools then lack the materials and qualified teachers needed to facilitate learning and encourage completion of high school or continuance to higher education. The shortage of teachers is perpetuated by underfunding that results in low salaries amidst a growing workload.59 As a result, states such as Texas and Alabama hire teachers without certification or with only emergency certification to teach in their schools amidst their funding crisis and teacher shortage.60

Contributing Factors

Government Policies

Government policies reduce funding in southern high schools because they dictate how much money goes into schools. State governments across the US are in charge of providing funding to the public schools. While most of this funding can be used to freely meet student needs, a portion of it is regulated by state governments for specific purposes. Legislators restrict this portion of funding by designating it for certain purposes, such as school maintenance, a new football field, or interest payments, because they believe that they know, based on their interpretation of student progress data, what will produce better test scores and higher graduation rates in public schools.61,62 Forty-eight percent of public school funding comes from various state resources such as sales tax, income tax, and fees. Another 44% of the school’s budget is derived from local districts, mostly from property taxes.63 With most funding coming from property, income, and sales tax, proposed tax increases are often met with public discontent in certain areas of the country; the way that the government funds public schools makes it difficult for budgeters to navigate the complex balance between politics and public values.64

In the South, 40% of eligible voters consider themselves to be Republican; this is almost 2 times the amount of Democrat voters in the South at 21%. 65 Tax cuts are actually a somewhat bipartisan issue; however, Republicans and Democrats approach tax cuts in different ways. Republicans favor tax cuts for the wealthy and for businesses, while Democrats favor increasing taxes for the wealthy and businesses and reducing taxes for lower-income Americans.66 In Republican states, state tax cuts typically favor the wealthy and deplete public school funding.67,68 This is not to say that there are no benefits to tax cuts; tax cuts often boost the American economy and improve income distribution. However, this growth is not enough to offset the loss in revenue for schools.69

In 2006, the Taxpayer Relief Act was passed, which restricted property tax growth. At this same time, the average budgeted amount for state-mandated pension contributions in public schools increased from 0.64–1.09%, taking away funds that could be used for educational purposes. These two acts of government caused school budgets to be severely strained because they reduced the per-pupil spending, especially with the occurrence of the recession from 2007–2009.70 Government entities often overlook education in the competition for more public funds because its economic benefits are not as immediate or clearly seen as those of other publicly funded institutions such as NASA, the US Department of Defense, and many national laboratories.71 In 2008 school budgets were cut due to the recession, and in 2015, 29 states in the US were still providing less per-pupil funding than they were in 2008. Rather than restoring funding, historically, legislators in Mississippi, North Carolina, and Oklahoma cut income tax rates, costing schools millions of dollars in much-needed funding.72 Although these funding cuts occurred more than a decade ago, schools are still having to catch up to current inflation rates.73

Racial Disparity

Racial disparities in the public school system today affect educational and economic outcomes for southern high school students because there is a higher proportion of black students in the South. The average percentage of black students in public schools in the South in 2021 was 23.25% compared to the rest of the United States, which on average housed 10.6% of black students.74 This means the American South holds almost 10% more of America’s black population in its public schools than all other regions of the United States.75 Black and Hispanic students are also more likely to live in school districts that have low educational funding.76

An example of racial disparityDisproportion in the way racial groups are treated when it comes to income, education, economic status, and so on. comes from a rural school district in Louisiana where the graduation rate for black students in 2019 was 61%, almost 30 percentage points less than the rate of white students at 90%. White students often outperform black students in standardized testing such as the ACT or SAT.77 Student retention rates and standardized test scores act as incentives that determine a school’s access to additional funding from the federal government; lower levels of performance result in less financial aid.78

Structural inequality, such as underfunding in schools with high populations of black students, is a result of centuries of discriminatory public policy that has only recently been remedied.79 An example of such a policy is redliningA discriminatory and illegal practice in the United States where a mortgage lender or insurance provider restricts or denies services to certain applicants in certain communities because of the racial characteristics of their neighborhood.. Redlining began in the 1930s and ended in 1968, but it still affects people of color in those 7,148 formerly redlined neighborhoods; economic inequality is more prevalent and carries over into educational funding.80,81 Of the neighborhoods that were redlined many decades ago, 74% are considered low-income, and 64% are minority neighborhoods today.82 People in what were previously redlined neighborhoods now face underdevelopment of infrastructure, high crime rates, and low quality of education. Because of underdevelopment, property taxes decreased along with the property values, which are 4.8% lower than in surrounding areas; lower property taxes result in less money going into public schools.83,84 School districts located in formerly redlinedA discriminatory and illegal practice in the United States where a mortgage lender or insurance provider restricts or denies services to certain applicants in certain communities because of the racial characteristics of their neighborhood. neighborhoods generate less per-pupil revenue, and although they receive more state and federal per-pupil revenue, it is not enough to close the gaps with non-redlined districts. This is because per-pupil expenditures are higher in formerly redlined neighborhoods as a result of their larger shares of low-income students.85 The underlying and historical racism in the laws and institutions of the US has long proved to be a setback for high school students in the Southern United States, where public schools house a large portion of students of color.

Economic Insecurity

The Southern United States is also adversely affected by economic disparity, which negatively impacts school funding as public schools are funded primarily by the public. The average annual wage in the southern United States is $53,199.33 while the average for non-Southern US states was $60,878.86. Mississippi had the lowest average wage of $45,180, and New York had the highest with $74,870; that $29,690 difference is enough money to pay for one full semester of college on average.86 However, the unemployment rate in the South, at 3.2%, is actually lower than all other US regions; the Midwest had a rate of 3.3%, the Northeast region a rate of 3.5%, and the West a rate of 4%. These numbers illustrate that while more people are employed in the South, they are employed in lower-paying jobs.87 Low-paying jobs could be considered in this case as jobs that pay at or below the minimum wage and by the hour. This includes, but is not limited to, restaurant service jobs, retail work, and construction work. South Carolina, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Virginia (all Southern states) are the 5 states with the highest percentage of workers earning at or below the federal minimum wage.88 This disparity is due to a lack of business regulations and labor protections in this region of the United States. This lack of protection contributes to wage theft in the South; as of 2023, the federal minimum wage is $7.25 per hour, while some southern states do not have a minimum wage, and Georgia’s minimum wage is $5.15 per hour.89 Although these states set this as their minimum wage, they are required by the Federal Fair Labor Standards Act to pay workers the federal minimum wage.90 The fact that they follow the federal minimum wage rate shows that businesses in this region will often only accommodate workers up to the bare minimum that the federal government has set rather than being concerned with their economic security; many other states have set their minimum wage higher than the federal minimum to keep pace with inflation rates.91 Even after adjusting for the low cost of living in the South, median wages remain to be some of the lowest in the nation.92

Take the minimum wage in Georgia as an example; if you work full-time for $7.25 per hour, you make $15,080 a year or $1,256 a month before taxes. On average, 34.9% of income is dedicated to housing costs, so that means someone in this position could only be spending about $438.58 per month on housing to meet that national standard.93 To put this in perspective, the average cost per month of a one-bedroom apartment in Atlanta, Georgia is $1,993.94 The economic underdevelopment in the southern US has led to high rates of poverty and the underfunding of public services such as public schools.95

The cycle of low-paying jobs contributes to the underfunding of public high schools in the rural south. Because so few employment opportunities in these communities require a high school diploma or a college degree, priority is not placed on the education of adolescents but rather on job training in blue-collar labor industries such as plumbing, construction, and electrical work.96 As a result, students and their families do not take high school education or its funding seriously and the cycle of economic disparity continues on from generation to generation, perpetuating the lack of funding in schools in rural communities.97 This is not to say that jobs in blue-collar fields are less valuable; jobs in these fields are necessary and accessible. However, having the option to attend college can make a difference in the life of an individual. Among the population with the lowest socioeconomic status in the US, 44.3% never enrolled in college.98 A college degree gives an individual more career options in higher-paying fields; Attainment of higher education increases the chances of employment for 25–34 year olds in the US The employment rate for those with a bachelor's degree or higher was 87% compared to those who had not completed high school at 61%.99 The prevalence of low-paying jobs creates a problem in the South, where state and local taxes that fund public schools are already low; additionally, the lack of fair wagesA wage fairly corresponding with the value of the services rendered. contributes to the region’s tendency to pass policies that do not favor increased funding for already underfunded schools.

Consequences

Dropouts

A negative consequence that comes as a result of the underfunding of public schools is more high school dropoutsA student who does not complete their schooling and therefore does not receive a high school diploma. because underfunded schools will not offer extracurricular activities that appeal to students, and the poor quality of educational resources negatively affects student retention. The National Center for Education Statistics found that in 2016, about 7% or 2.6 million people in the US between the ages of 16–24 were not enrolled in high school or did not have high school credentials.100 High school dropouts are a result of a combination of many things that affect a student’s life, but among those factors are school resources, structures, and processes; each of these factors is affected positively or negatively by school funding and budgeting.101 School resources, influenced by underfunding, include teacher salary and qualifications, class size, and per-student instructional expenditure, meaning how much of the school’s budget is being spent on the instruction of one student.102 Budget cuts typically result in larger class sizes, fewer teachers, and the elimination of extracurricular activities that act as incentives for students to stay in school. Without the resources and staff to help kids who are falling behind and the incentivizing nature of electives and extracurriculars, public schools struggle to retain students until graduation.103 Schools that increased funding by 12% saw graduation rates rise between 6.8–11.5%; this correlation provides strong evidence for the claim that increased funding for school resources results in higher graduation rates.104

Dropping out of high school poses many long-term negative consequences for young individuals and for the US economy. These individuals face a future with fewer job opportunities, lower salaries, higher rates of incarceration, and a lack of high self-esteem and psychological well-being.105 More than 21% of individuals between the ages of 20 and 24 who did not complete high school were unemployed in 2015, compared to about 14% of high school graduates; even if a dropoutA student who does not complete their schooling and therefore does not receive a high school diploma. does find a job, they earn about 25% less than those who graduated.106 Many of these consequences reduce the quality of life and perpetuate economic disparity in the region. Because dropouts are more likely to have poor health and be incarcerated, they require more public assistance, costing governments millions of dollars; it is estimated that if the dropout rate were cut in half, it would save the government more than $45 billion.107 The cycle of low-paying jobs and government expenses caused by dropouts is significant to the issue of underfunding because it perpetuates the lack of school funding, and government funds that could be spent in public schools are instead being spent on these individuals and communities.

Lack of Access to Mental Health Resources

Photo by Galina Zhigalova on Istock

The underfunding of schools in the South also causes public high school students to have less access to mental health resources because they lack the budget to implement them correctly. The Mental Health Technology Transfer Center (MHTTC) conducted an assessment of the needs of state leaders in the southeast in 2019; among the top priorities identified was school mental health.108 Access to mental health resources is particularly a problem in poor, rural school districts of the United States, of which the South has many. Twenty-two percent of southern 5–17-year-olds lived in poverty-stricken families in rural district locales, higher than any other US region.109 Children from low-income households are far more likely to access mental health resources only at school rather than from outside sources that only take private insurance.110

Many assume that because of small populations and lack of density, rural districts in the south have a smaller need for mental health resources; this assumption is flawed. On average, in the US, 20% of school-aged children face serious mental health issues, and few of them receive the care that they need, but mental health issues are even worse in low-income rural areas because of geographic isolation and the lack of resources due to underfunding.111 If a public school is underfunded, it will not have the resources to accommodate the need.

Because of underfunding that creates a lack of mental health resources, severe mental health problems have developed among students in public schools in the South. For example, one study found that depression is especially prevalent among both boys and girls in rural high schools. Differing from other studies from other regions of the US, the adolescent boys in this particular study reported just as many depressive symptoms as the girls. The unique results of this study led researchers to conclude that intervention and prevention from schools were especially needed in this case.112 Because schools in the rural south are severely underfunded, they have little to no funding available to contribute to mental health services for students. The National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) recommended a ratio of 1 school psychologist for every 500–700 students in order to meet the needs. Due to a lack of funding and resources, schools on average, have a ratio of 1 psychologist to 1,408 students.113 An increase in the number of school psychologists to meet the recommended ratio would require a 0.45–0.8% increase in educational funding.114 Statistically, rural public schools have the hardest time providing resources for proper diagnostic assessments and treatment by mental health professionals in schools.115

Behavioral Problems

Public schools that are underfunded tend to have less experienced staff who do not have the capacity to deal with students’ behavioral problems because there is no room in the budget to provide them with the tools and training to find the underlying issues causing them.116 Teachers at underfunded schools are often new to the profession, lack important skills in classroom management, and tend to resign more often. Frequent resignations lead to high teacher turnover, and turnover, combined with a lack of classroom experience, is correlated with behavioral challenges inside and outside of the classroom.117 Some potential behavioral issues that students face are truancy, a lack of classroom engagement, and a lack of emotional self-control; schools in underfunded districts face higher levels of students who pose threats to school or physical safety.118 In 2022, public schools reported a 56% increase in classroom disruptions, a 48% increase in acts of disrespect towards teachers and staff, a 48% increase in rowdiness outside of the classroom, and a 33% increase in chronic absenteeism.119 These behavioral problems are likely due to stress and trauma, but the way that teachers interact with such students has the potential to exacerbate the problem. Teachers in underfunded schools who tend to have fewer skills and less experience may find that they do not have the capacity to use the type of discipline and methods of teaching that students will respond positively to.120

After the COVID-19 pandemic, beginning in 2020, 84% of public schools reported that they saw an increase in behavioral issues among students; these rates are predicted to rise as the long-term effects of the pandemic unfold.121,122 The lack of funding from state and local governments has forced the federal government to step in with temporary relief through the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Act (ESSERA), which has provided public schools with $122 billion to help in their recovery.123 Currently, public schools need funding now more than ever to accommodate more mental health staff, training on student support and classroom management, and more staff in general.124 Teacher turnover and a lack of experienced teachers have a negative impact on public schools and teacher-student relationships as they undermine efforts in school improvement, increase class sizes, and cut the amount and types of class offerings. Turnover rates for teachers are highest in the south, reaching between 14–17%.125 Teacher turnover is detrimental to teacher-student relationships and causes relationships that are conflictual in nature; this conflict is often manifested in the student’s negative outward behavior.126 Not only does the issue of teacher retention cause consequences in the present, but it also negatively affects a student’s life further down the road by perpetuating delinquency, school failure, and substance abuse issues.127

Practices

Organizational Finance Training for Administrators

School administrators are most often former teachers. Almost all principals were teachers before becoming principals, and only about half have previous school administration experience.128 In 2021, public schools saw a decrease in administrators with 20 or more years of experience compared to a decade ago.129 When individuals transition from teaching to administration, it is not a guarantee that they will receive any financial training. Each state has different requirements for becoming an administrator; most states require a master's degree, some teaching experience, and the completion of a preparation program.130 One of the biggest downsides of the current principal certification system is that principals are often not required to complete training in organizational finance. Because each state’s requirements are different, it is hard to say whether administrators in certain schools have the financial and budgeting skills or qualifications to make smart financial decisions when it comes to budget allocation.131

A great example of an organization that has already implemented organizational finance training for administrators is WestEd. WestEd is a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting equity in education.132 One of their initiatives is interactive finance training for school leaders. Their training “[focuses] on internal controls and practices needed to comply with complex federal requirements.”133 They help administrators understand government policies such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), Education Department General Administrative Regulations (EDGAR), and Uniform Grant Guidance (UGG). This helps the school employees in charge of their school’s budget to understand how they can best use federal funds.134 The National Business Officers Association (NBOA) also offers an online course to school administrators to help them make the best use of funds when finances are tight and to work more efficiently with leadership when it comes to finance practices.“135 This program is specifically for administrators who do not have a background in business. It focuses on understanding financial models and terminology as well as finding ways to promote financial sustainability.136

Impact

WestEd does not list any clear measurements of their impact on school underfunding. They do list their learning outcomes, which include: understanding and resolving misunderstandings of federal policy surrounding fiscal requirements, improving the ability of internal controls and procedures to meet federal grant requirements, and removing barriers to innovations that would improve student outcomes. Additionally, this webpage lists who will benefit from their program, including business managers, special education administrators, federal program administrators, superintendents, and other school administrators.137 WestEd does not have any empirical measurements of the program results. NBOA has even less information regarding impact measurements. They briefly explain what their program teaches and give an outline for each week of the course.138 Week 1 focuses on learning to allocate school resources based on the school’s mission and goals, while Week 2 teaches about leveraging the environment that your school operates within. The final week is a culmination of the other 2 weeks and a chance to hear from financial experts.139

Gaps

The primary gap in this practice is the lack of impact evaluation and measurement. Without measurements, there is no way to know if these programs are improving conditions of underfunding in public schools. These two practices are both online courses, making them very accessible and scalable in the sense that anyone in the United States with internet access could participate, but they also cost a lot of money. NBOA’s course costs between $505–750 while WestEd’s costs $360 for the full course.140,141 It is difficult to pinpoint where this money is coming from, as it is unclear whether administrators are to be sponsored by their already underfunded schools to take this course or if they must pay out of pocket. This issue makes the practices less accessible and appealing to administrators who are already struggling to make ends meet.

Changes in Government Policy

Changes in government policy have the ability to reduce underfunding in public schools. Some of these policy changes may include changing how schools are funded from being primarily state-funded to increasing the amount that is funded federally. These changes could also include enacting policies that will change the distribution of funds according to need rather than geography. It is difficult to identify changes in government policy when it comes to educational funding in the US because the practice of funding schools primarily through state and local government tax collection has been in place since the early 19th century.142 Looking outside of the US at some of the world’s top-performing public school systems is helpful in determining some policies that the US might consider adopting.

Photo by Shironosov on Istock

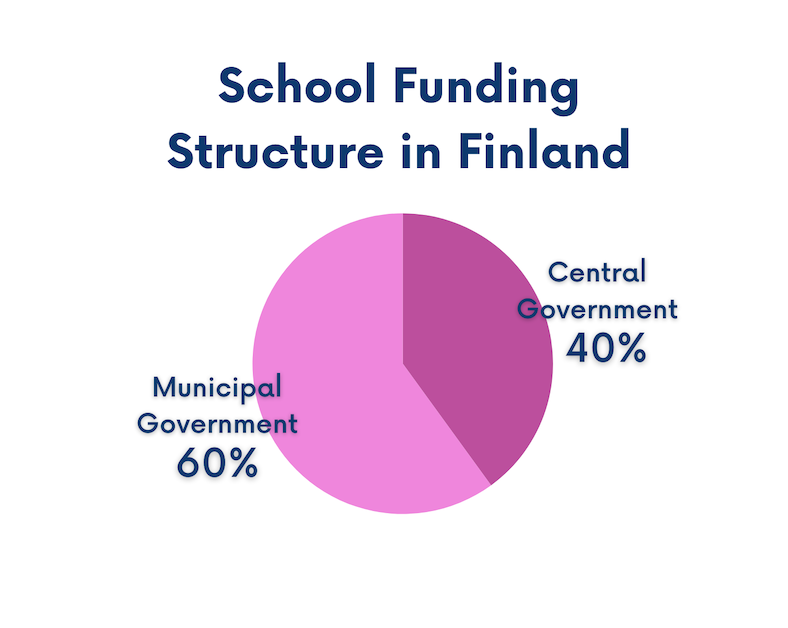

According to the National Center on Education and the Economy, some of the top-performing countries in education were Canada, Estonia, Finland, Hong Kong, Japan, Poland, Shanghai, Singapore, Korea, and Taiwan.143 In Canada, schools are funded primarily at a provincial level; this is comparable to funding at the state level in the US Instead of collecting taxes and distributing them based solely on location, provinces have centralized school funding and collect taxes and distribute them to schools based on number of students, special needs, and location.144 In Finland, about 40% of funding is provided by the central government and 60% by municipal governments and is distributed according to the number of children and the yearly calculated cost per child; this practice helps undermine the inequities of unequal per-pupil spending. The Ministry of Education and Culture provides additional funds to schools with students who may face disadvantages such as being from a low-income family, a single-parent family, or having parents who are unemployed.145

Impact

Research on educational achievement from either Canada or Finland is limited. Some outside evaluations provide a small glimpse at the impact that their educational systems have had on student outcomes. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is a program that measures the skills of students around the world through tests in math, reading, and science; these tests are meant to gauge problem-solving skills rather than memorization of facts.146 Out of the 25 countries that participated in the program the US was #22 with a score of 1,485; Canada and Finland were #6 and #7 with scores of 1,550 and 1,549.147 The US had a PISA score of 478 on the math portion, while Canada had a score of 512 and Finland had a score of 507.148 In Finland, about 93% of students graduate from academic or vocational high schools.149 These differences in student outcomes reflect the gaps in the American educational system, especially in the way that it is funded.

Gaps

One gap in this practice is that changing long-implemented national policy is extremely difficult and would take a long time. The United States system of government requires getting many people with opposing views on the same page, but American politics are far too partisan and transitionary.150 America operates through a federal system in which states have a major impact on policy; Canadian and Finnish governments operate quite differently.151 Another gap involves evaluating the impact data of this practice. It is difficult to attribute the higher test scores or graduation rates in other countries specifically to their funding policies. There are many differences between these schools and US schools that could also account for the impact; all that this proves is that there is a correlation between different systems of educational funding and higher student achievement.