Gender-Based Violence Against Women in South Africa

By Lacey George

Published Summer 2020

Special thanks to Sam Lofgran for editing and research contributions

+ Summary

Dubbed the "rape capital of the world" by Human Rights Watch, South Africa has some of the highest rates of gender-based violence worldwide, including rape, female homicide, and domestic abuse. The women in South Africa are faced with pronounced challenges, stemming from a historical background of apartheid-era oppression, when it comes to equality. Some of the most significant challenges that contribute to South Africa’s gender-based violence problem include a lack of government action in legal implementation, pervasive patriarchal cultural attitudes, and widespread poverty. Gender-based violence affects everyone in society—the women themselves, their children, and the men who perpetrate the crimes. Gender-based violence is a threat to the mental, physical, and reproductive health of women, increases the incidence of homicide, contributes to the HIV/AIDS crisis, and places families at risk. Leading practices for the mitigation of gender-based violence include educating boys and men in the fight for equality, supporting women who have been victimized, teaching self-defense and empowerment classes, and monitoring the failings of government entities.

+ Key Takeaways

- The female homicide rate in South Africa is roughly 24.6 per 100,000 population—nearly six times the global average.

- Despite enacted legislation and general government action, there has only been a 6% decrease in rape rates in South Africa since 1996.

- Roughly 28% of South African men admitted to raping at least one woman, and 46% of those admitted to being repeat offenders; further, 7.7% admitted to raping ten or more women or girls.

- Patriarchal culture and the historical precedent of inequality have exacerbated the inequality that exists between men and women in South African society.

- When viewed holistically, it is clear that the effects of gender-based violence influence all members of society, not just women.

- Mitigating gender-based violence requires treating it as a societal problem rather than assuming it is a "women’s issue." Engaging men and empowering women in the fight for gender equality produces results—in communities where men are educated about gender-based violence, the status of women improves.

+ Key Terms

Gender-based violence—An act of violence that is committed against a person’s will and stems from gender norms or cultural power inequalities.1

Sexual violence—Any sexual act that occurs against someone’s will, including sexual advances, comments, or efforts to obtain sex by means of threat or coercion.2

Intimate partner violence (IPV)—Physical, sexual, or psychological harm inflicted by a past or current romantic partner or spouse.3

Domestic abuse—Any violence or emotional abuse committed by a family member or intimate partner.4

Context

When Nelson Mandela was elected in 1994, it brought to an end the decades-long struggle against the apartheid regime, which was rooted in the hegemonic European colonization of South Africa. Perhaps for the first time in the country’s history, democracy and equality seemed like tangible realities. Prior to the abolishment of apartheid, violence by the dominant group against the disempowered was legitimized by cultural and legal practices.5 The injustices of apartheid were most clearly manifested in racist policies that gave white South Africans rights and status that their Black peers were deliberately deprived of. However, these inequalities and methods of dominance extended ubiquitously across all social minorities, including women. Under apartheid, citizenship was granted only to men, and women were classified exclusively as dependents. Remnants of this standard persisted in the post-apartheid law that restricted protections for women, particularly in cases of gender-based violence.6

During apartheid, very few legal and social structures existed to protect women against gender-based violence, and the judicial system that did exist was generally detrimental to the protection of victims. Apartheid-contemporary research conducted in 1994 found a high prevalence of rapes against older women using bottles and tin cans as penetrative weapons, as rape was only recognized by the South African government of the time if the perpetrator used his penis to penetrate the victim; the harshest legal charge rapists who utilized objects could recieve was assault.7 The South African Department of Justice had no established sentencing guidelines for rape and other kinds of sexual assault, leaving judges to use their own biases to inform cases. For many years, the "Cautionary Rule" was in effect, which required the courts to use extreme scrutiny when evaluating the validity of women’s rape testimonies that were uncorroborated by physical evidence or eyewitnesses. As a result, many women were discredited, and in 1992 rape cases had a conviction rate of only 53%, while perpetrators of non-sexual assault were convicted at a rate of 86%.8 This created a subjective judicial landscape wherein sexual assault charges varied wildly, and women were not taken seriously when they recounted their lived experience of assault.9 Additionally, the state condoned the corporal punishment of wives by their husbands. At the time, wife-beating was both normalized and legal, creating an environment in which domestic abuse was rampant and virtually unpunishable.10

Despite the social progress that has been made in South Africa since 1994, the lack of effective support offered to victims of gender-based violence and women in general remains problematic. Systemic discrimination against South African women has been addressed by many government and social ventures, but cultural gender inequality persists, clearly evident in the gender-based violence that is prolific throughout South Africa. Gender-based violence is wide in scope and pervasive in its multidimensionality, including such crimes as intimate partner violence, domestic abuse, and sexual violence, such as rape.11 Definitions of rape vary from country to country, and understanding South Africa’s legal definitions inform the statistics and discussions in this brief. The 2020 legal definition of rape in South Africa includes any intentional penetrative intercourse with a woman without her consent. The legally recognized age of consent is 12, and any penetrative intercourse with a girl under the age of 12 is always considered rape.12 Marital rape was not recognized as a criminal offense in South Africa until the creation of the Prevention of Family Violence Act of 1993, which stated that "a husband may be convicted of the rape of his wife."13

Approximately 200,000 South African women per year report some type of violent physical attack against them to the police.14 More than 40% of South African men interviewed disclosed being physically violent towards a partner, and 40%–50% of women interviewed identified as victims of some type of intimate partner violence.15 Data compiled by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2012 reported that approximately 60,000 women and children are victims of domestic abuse in South Africa every month, which is the highest reported rate globally.16 In 2009, female homicide by intimate partners in South Africa was reported at a rate of 24.7 per 100,000 people, more than six times the global average.17 Rates of physical and sexual gender-based violence against female sex workers (FSWs) are especially high, with a sample of FSWs in Soweto, South Africa reporting liftetime rates of gender-based violence as high as 76%.18 Occurrences of gender-based violence are inherently hard to account for, as many go unreported, but factors specific to South Africa make the numbers even more likely to underrepresent the scope and frequency of the violence.

In addition to the high prevalence of gender-based violence against women, South African girls also often become victims of gender-based violence. Approximately 39% of South African girls experience some form of sexual violence as minors.19 Startling cases of "baby rape" came into the spotlight in 2001, when 6 men gang-raped a 9-month-old girl, leading to investigation of past child rape incidents dating back to the 1990s.20 These crimes have continued to occur and gain publicity in South Africa, and the most recently publicized baby rape case happened in 2019.21 As recently as 2006, nurses in some parts of South Africa encouraged mothers to bring their daughters into local clinics to receive contraceptive injections as soon as they started menstruating, given the likelihood that they would be raped more than once as a teenager.22

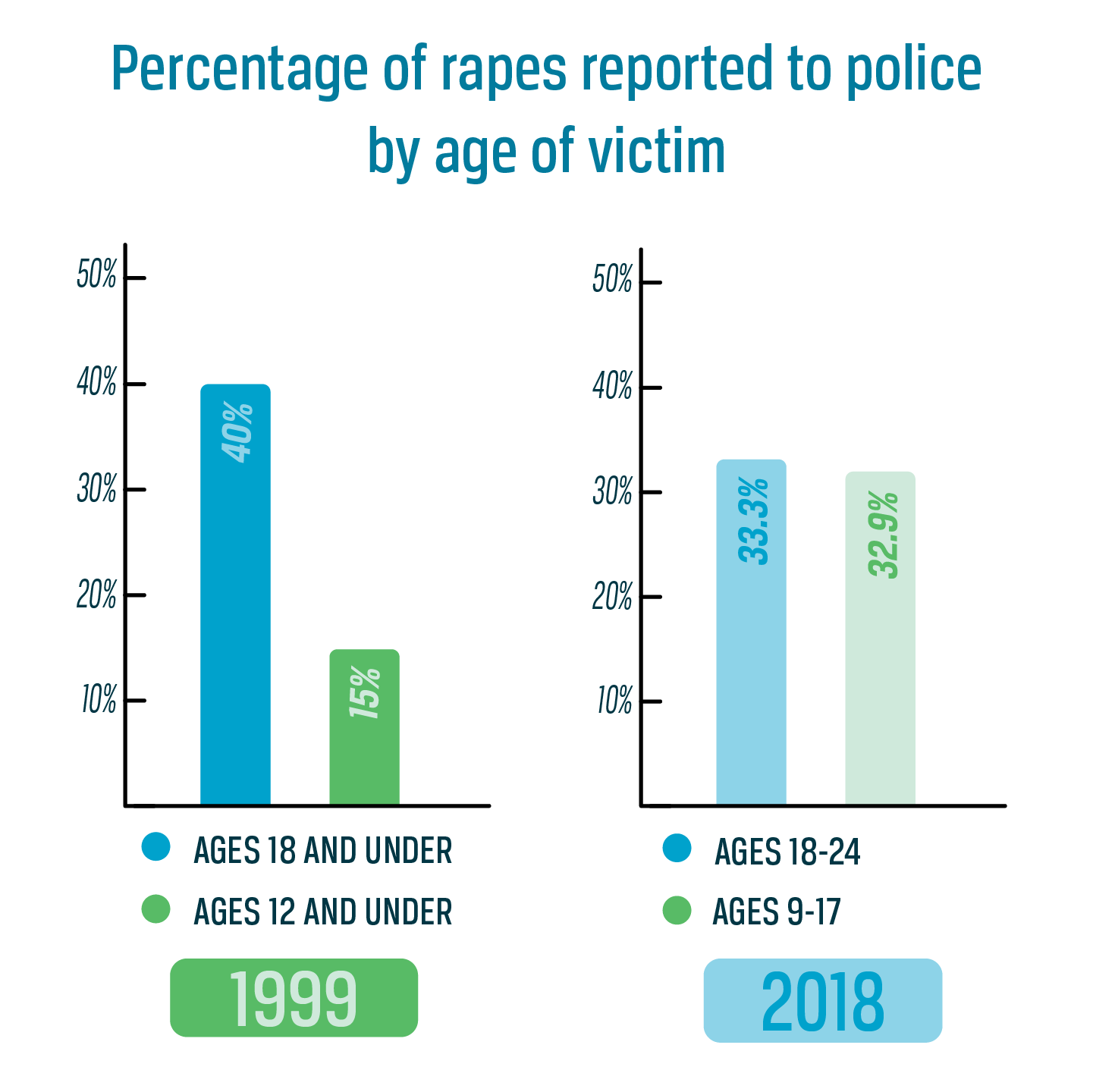

In 1999, 40% of victims who reported rapes to the police were under the age of 18, and 15% were girls under the age of 12.23 Twenty years later, not much has changed; a 2019 analysis by the South African Police Services (SAPS) showed that in 2017 and 2018, 33.3% of rape victims in the Northern cape were between 18 and 28 years old and 32.9% were between 9 and 17 years old.24 According to SAPS, the total 2019 reported rape rate is 90.9 per 100,000 people.25 However, SAPS estimated that only 1 in 36 cases are actually reported to police; by this measure, there could have been more than two million additional rapes that went unreported.26

Present problems with deficient gender-based violence prevention and incorrect reporting can be traced back to apartheid. During apartheid, statistics of rape and other forms of gender-based violence were consistently under-reported, particularly the assaults of Black women.27 Black women were afraid to report any sort of crime to the police, let alone their own experiences of gender-based violence. This was due to inaction by the police and the fear of being perceived as a police informant, which in those days sometimes led to homes being burned down and the informant being killed by other members of the community.28 Due to a system that widely lacked accurate reporting, the reported incidences of gender-based violence during these years are likely far from accurate. In 1994 it was estimated that approximately 1 in 4 women had experienced rape, with the average age of first sexual assault being 14.29 Just as during apartheid, Black women continue to be disproportionately silenced in the realm of gender-based violence today, and while the numerical statistics of unreported rapes are nearly impossible to measure, the culture of impunity that was established under apartheid remains embedded in modernity.30

In a study conducted by the South Africa Medical Research Council (MRC) in 2009, 27.6% of men interviewed admitted to raping a woman or girl. Additionally, 46.3% of those men admitted to repeat offenses, and 7.7% of self-admitted repeat offenders reported raping 10 or more women.31 That same year, the makeup of imprisoned rapists in South Africa was analyzed, and it was revealed that Black men were the most commonly convicted perpetrators of rape.32 This was true during the times of apartheid as well; Black men were commonly hanged for rapes, but only if the victim was a white woman.33 Under apartheid, no white man was sentenced to death for rape. Both of these facts reveal the racism of the legal system at the time—only crimes committed by Black men or against white women were worthy of legal action.34 The fact that Black and mixed-race men are convicted for rape at a higher rate is attributed largely to the fact that Black and mixed-race people make up approximately 90% of the South African population.35 Black and mixed-race men were the perpetrators of 27.1% and 45.7% of rapes, respectively, while white men perpetrate 11.1% of rapes.36 Despite the approximate population proportionality of these statistics, stubborn apartheid-driven beliefs that Black men are more aggressive and violent than white men persist and likely have consequences on conviction and incarceration. For example, in 2016, white South African judge Mabel Janson tweeted that the "rapes of baby, daughter and mother" are a "pleasurable pastime" for Black men, revealing strong modern remnants of apartheid-esque racism in the South African justice system.37

Contributing Factors

Lack of Policy Enforcement

A combination of law enforcement officials’ dismissive attitudes towards sexual assault and a lack of legislative enforcement has lead to the continued propogation of gender-based violence in South Africa. The fact that there has not been any statistically significant reduction in gender-based violence over the past 20 years underscores the difficulty the government has faced when trying to enforce legislation relating to the issue.38 Following the creation of the South African government as it stands today, many government initiatives and committees addressing the betterment of women’s status in South African society have been instituted. However, despite the sweeping nature of policies and the intentional adherence to the national Constitution, high rates of gender-based violence continue to pervade South African society.39 Recent policies and initiatives have been compact and progressive, stemming from the South African Constitutional statement that "every person has the right to freedom from all forms of violence from either public or private sources."40 The policies are also relatively comprehensive, and the preamble to a 2017 bill stated that the purpose of the legislation was the "promotion of gender equality, the prohibition of unfair discrimination against women, and the elimination of gender-based violence."41

A major factor that contributes to the lack of legislative effectiveness is the attitudes of local law enforcement and judicial committees. The South African Department of Justice has openly described its weaknesses with "huge bureaucratic inefficiencies, wastefulness, [and] not obtaining value for money for the resources it has deployed."42 The conviction rate for sexual crimes in South Africa is between only 4% and 8% of reported cases, and since many rapes go unreported, the overall conviction rate of rapists and sexual predators is much lower.43 In addition to the bureaucracy that characterizes South African courts, the personal beliefs of judges and police officers could also contribute to the low rate of conviction.44 In a 2017 study, 54.2% of rape victims who had gone to the police reported that no witnesses involved in the case were interviewed by law enforcement. Additionally, 37.5% of respondents reported that the police did not make any effort to compile evidence about their assault, underscoring the problematic way in which individual law enforcement officers can affect the trajectory of a case.45

Many times, victims of gender-based violence are subject to secondary victimization when they experience additional harassment from law enforcement. Women are forced to give testimonies in public against their will, and during questioning and cross examination it is frequently implied that, due to their wardrobe choices or actions, they deserved the violent treatment from their rapist or offender.46 Secondary victimization has been linked to the withdrawal of charges at all stages, including reporting. Additionally, secondary victimization was correlated with the discouragement of other women, causing them to feel as though reporting to the police would not result in justice being served.47 In a 2017 study, 37.5% of victims who had reported their assault rated the empathy of the police as "bad" or "very bad"; of all the victims in this study, 62.5% said that they would not report future victimizations to the police, as they felt the exercise was pointless.48 Without grassroots enforcement of gender-based violence laws on the local level, top-down governmental action is rendered completely ineffective.

Social and Cultural Views on Gender

Because the constitution of South Africa was written in 1994, more recently than other similarly developed nations’ constitutions, the country “is currently struggling to balance one of the most inclusive and progressive Constitutions in the world with its largely patriarchal and culture driven society."49 Some of the patriarchal undertones within South African society may be associated with the cultural history of indigenous tribes. In traditional South African tribes such as the Valoyi, women would have been ineligible to own property or to become leaders in the tribe because of their gender.50 Even today, some rural laws dictate that if a married man dies, his house and property pass to the nearest living male relative rather than his wife and children.51 Additionally, there is a historical power imbalance that precludes women from having autonomy over their marriages and families or access to political power.52 These male-dominant power structures flourished under the apartheid regime. In 2013, almost 20 years after the abolishment of apartheid, a controversial bill was proposed that gave tribal and traditional leadership even more power.53 The bill was a double-edged sword: while it restored power to tribes that had been colonized and discriminated against under apartheid, it also placed the 47% of South African women who lived in rural areas under traditional leadership at greater risk of being subjected to sexist leadership informed by traditionalist views of gender.54 Traditions of gender inequality are built into the history and culture of South Africa, and the inextricable cultural link between power, dominance, and maleness manifests itself in the gender-based violence that is highly normalized in South African society.

In modern South Africa, the male identity is still strongly tied to ownership of or stewardship over a woman and children. Without a wife and children, an adult man is still considered a boy.55 This cultural prerequisite to manhood conditions men to view women as something to be obtained and controlled rather than autonomous individuals, which emphasizes the idea that women are weaker and should be subordinate. These attitudes about power, however, are not exclusively found in men; in a provincial study about attitudes toward sexual violence, 59% of women agreed that sexually violent men were more powerful, and 9% said that they were more attracted to sexually violent men.56 The conflation of power and violence, particularly gender-based and sexual violence, exacerbates and normalizes the idea that women are inferior to their male counterparts and that there should be no consequences to men exerting physical, emotional, and mental dominance over women. Additionally, the belief that women are at fault for rape is prevalent among both South African women and men: 22% of women interviewed reported that they believed that rape victims brought it upon themselves, and 26% of men interviewed did not think that women hated being raped.57

Rape has become an expected part of life in South Africa and is condoned to the point that perpetrating violence against women has a limited effect on a prominent man’s political career—something that is occuring in other countries as well. South African parliamentary chief whip Mbulelo Goniwe was charged for requesting sexual favors from his intern but was not removed from office for more than a year after his conviction in 2007.58 Jacob Zuma, a prominent politician, was placed on trial for rape in 2006.59 Even after openly admitting that he and the victim had sex, Zuma was ultimately acquitted of the charges.60,61 Zuma later went on to serve as the president of South Africa for almost a decade, from 2009 to 2018. Zuma is not alone; in 2017, Deputy Minister of Higher Education Mduduzi Manana assaulted three women outside of a Johannesburg nightclub. Manana was sentenced to a year in prison, but was allowed to remain a backbencher in the African National Congress despite his conviction.62,63

Poverty

Poverty and the multitude of social problems that are associated with it are risk factors for the victimization of women and the continued propagation of gender-based violence. Generally, measures of violence such as homicides, major assaults, and gender-based violence are correlated with income inequality and lack of economic development. Violence indicators such as homicide, assault, and incarceration rates have been shown to be exaggerated in poverty-stricken areas. Although causation is difficult to establish due to the complexity of the issue, data shows that violence is more likely in nations where a larger proportion of the population is economically deprived.64 South Africa as a case study follows this correlation; in a statistical analysis of five countries with particularly high rates of violence, South Africa was shown to have both the highest homicide rate and the highest rate of economic disparity between the upper and lower classes.65

The circumstances resulting from poverty place women at greater risk of victimization. In 2015, 55.5% of all South Africans were living beneath the poverty line.66 In 2019, the South African poverty line was set at US$74.60 per person per month.67 Just as women are disproportionately affected by gender-based violence, they are also more heavily burdened with the weights of poverty. According to South Africa’s national data agency, in 2015 49.2% of South Africans living beneath the poverty line were Black women.68 Houses headed by females alone are consistently and significantly more poverty-stricken than others.69 Homelessness, housing instability, and distressed urban settings are all risk factors for gender-based violence, placing women who live in poverty in greater danger of experiencing violence.70

Women who live in poverty, as compared to their wealthier counterparts, are compelled to place a higher premium on having a partner who has some type of income. The patriarchal and heteronormative social landscape of South Africa can result in situations wherein poor women are exploited sexually by men in order to obtain money and other essentials.71 For example, in poverty-stricken South African mining regions, large groups of men fuel the sex trade, and as a result, women and girls in desperate financial situations from surrounding areas are trafficked or coerced into sexual slavery by gangs and pimps.72 In addition to a higher threat of sexual exploitation, women living in poor areas such as slums and mining towns have less readily available access to resources such as piped water, electricity, and in-home bathrooms.73 These women face risks of attack going to and from latrines and water sources, particularly at night when they are likely to be alone.74

Women who hold jobs with a steady income report lower rates of IPV.75 Additionally, in a study of young South African men, working a steady job was also found to be protective against IPV perpetration, indicating that an elevated socioeconomic standing of one or both heads of house decreases the risk of gender-based violence in the home.76 Conversely, higher levels of food insecurity are linked to increased levels of IPV. Conflict in the home is more likely when there is a lack of resources, and poor women who depend on their husbands for income are less likely to leave abusive relationships if it jeopardizes their access to necessities.77 Partnered women whose husbands had refused to give them money for household items were 12% more likely to report sexual violence incidences than women in more financially stable households.78

Consequences

Health

Mental Health

Psychological trauma is a hallmark of victims of gender-based violence. In a study conducted by researchers at Stellenbosch University in Cape Town, South Africa, 12.9% of 31 adolescent rape survivors were found to have some type of stress-related disorder, and 16.1% had anxiety specifically. Since the incident of their rape, 22.6% had undergone or were currently undergoing a major depressive episode.79 In 2013, the WHO stated that women who are subjected to non-partner sexual violence are 2.6 times more likely to experience anxiety and depressive episodes than women who have not been victimized.80 Additionally, women who are abused in the home are more likely to be suicidal.81 In addition to anxiety, depression, and suicidality, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is common in women who have experienced violence; the lifetime prevalence of PTSD in women who have experienced sexual assault is 50%82, and 94% of women who experienced sexual assault displayed symptoms of PTSD within two weeks of the incident.83 Without treatment, PTSD has been found to be correlated with substance abuse, psychiatric problems, academic deficits and school dropouts, criminal behavior, and health and relationship problems.84

Unintended Pregnancy

Women who are raped or coerced into sex are more likely to have unwanted pregnancies. Rape victims have little to no power over contraceptive use and may become pregnant as a direct result of their rape. Additionally, women who have experienced sexual coercion in the past are more likely to have risky sexual behaviors, placing them at higher risk for unwanted pregnancy.85 Forced first intercourse is also linked with higher rates of unintended pregnancy under the age of 18.86 In sub-Saharan Africa at large, it is estimated that 28% of all pregnancies are unplanned, and in some areas of South Africa, reports of unplanned pregnancy reached as high as 90%.87 Women with unintended pregnancies face a variety of health risks, often from delaying or foregoing antenatal care visits after they give birth.88 There are several possible explanations as to why these women may delay care, including a lack of education about why it is important, insufficient access to medical facilities, and inability to pay for proper care.89

Mother and Infant Well-Being

Unintended pregnancy is also correlated with instances of domestic abuse and violence in the home during the pregnancy, which place both mother and baby at risk.90 Studies conducted at the University of Pretoria in South Africa have shown that domestic violence against expecting mothers is positively correlated with preterm births and abnormally low birth weights,91 likely due to the fact that mothers who experience high levels of stress during their pregnancies are much more likely to deliver their babies before they are full term.92 Additionally, trauma symptoms in infants correspond with mothers’ trauma symptoms due to limited caregiving behaviors and impaired mental health;93 many infants who are born into homes where domestic abuse is prevalent have increased startle responses, extreme fussiness, and increased likelihood of developing PTSD later in life.94

Homicides

As of 2019, the country has a homicide rate roughly five times the global average.95 In South Africa, homicide accounts for approximately 56% of fatal injuries for people aged 15–34.96 In 2018, 2,771 women were murdered in South Africa—one female homicide victim every three hours.97 In one region of South Africa, a total of 30.61% of the unnatural deaths of women in the years of 1993 to 2015 were homicides.98

In the past, up to 50.3% of South African female homicide cases were reportedly linked to intimate partner violence.99 In reality, this percentage might be much higher, as this statistic only accounts for homicides in which there was evidence of previous IPV. In a series of interviews with men who were incarcerated for murdering their intimate partners, it was found that homicide was viewed as an avenue to a sense of control. Many of the men interviewed experienced economic instability or substance addiction but felt that control over the actions of a female partner was both feasible and socially expected, and if they lost that control over the actions of their wives or girlfriends, the social construct of their manhood was in jeopardy.100 The men interviewed revealed the ideology that the most radical way to control a wayward woman was to end her life. It can be inferred that in many cases of homicide by an intimate partner, South African men valued their societal idea of masculinity more than the lives of their partners.

Coinciding with South Africa’s abnormally high rate of adult female homicide, homicide rates are also particularly high among girls ages 0–4.101 According to the WHO, frequent victimization of infant girls and toddlers is generally associated with cultures that place greater value on sons than daughters.102 Child homicides in South Africa mirror the high rates of adult intimate partner murder. In the case of sexual homicides (homicides involving a sexual element, such as a rape), upwards of 92% of child victims in South Africa were girls, and only 1% of boy child deaths were catgorized as sexual homicides.103 This indicates that young girls are far more likely to experience lethal sexual violence than young boys.

HIV

Although the percentage of sexual abuse victims who contract HIV in South Africa is unknown, high rates of sexual violence are generally correlated with high rates of HIV. Of women living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, 40% live in South Africa specifically, which is consistent with the abnormally high rates of gender-based violence that exist there.104 Women experience a much higher incidence of HIV than men, demonstrated by the fact that within the 15- to 24-year-old age group of South Africans, there are five women living with HIV for every two men.105

Both the physical trauma that happens during gender-based sexual violence and the psychological trauma that follows have been shown to increase the likelihood of HIV contraction.106 HIV directly affects CD4 immune cells, which are recruited by the body to sites of injury. When physical trauma occurs during a violent rape, more CD4 cells move through the body to the trauma site, essentially giving the virus access to a higher volume of CD4 cells and increasing the likelihood of HIV transmission. Psychological trauma is also associated with immune suppression, decreasing the likelihood of the body being able to handle the HIV viral load and exacerbating HIV contraction and symptoms.107

Male perpetrators’ higher rates of risky sexual behaviors, such as increased likelihood of having multiple concurrent sex partners and higher rates of physical violence against those partners, further increase the likelihood that men committing sexual violence are infected with HIV and other STIs.108 Of men that admitted to raping a woman, 46.3% admitted to repeat offenses.109 Due to the probability of victims being attacked multiple times and the likelihood that perpetrators commit more than one rape, victims of gender-based violence are at higher risk of HIV contraction.110

At the intersection of gender-based violence and HIV lies one of the most at-risk populations within South Africa: female sex workers. FSWs are highly likely to experience gender-based violence, and their profession places them at high risk of contracting HIV. In sub-Sarahan Africa at large, the rate of HIV prevalence in female sex workers is 29%.111 In South Africa, however, HIV prevalence in female sex workers ranges from 39.7% in Cape Town to 71.8% in Johannesburg, underscoring the comorbidity of high rates of sexual violence and HIV.112

Risk to Children’s Well-being

The epidemic of violence in South Africa affects children as well as women. Children who grow up in families where domestic violence is commonplace are more likely to be the victims of child abuse.113 Young girls are at high risk of both physical and sexual violence, and victims face consequences both in their youth and later in adulthood. Roughly 34% of South African children experience sexual abuse as opposed to the global average of 23%.114 Child sexual abuse is also a risk factor for later violence, and women who experienced sexual violence in their youth are more likely to be revictimized as adults.115 The corporal punishment of children by their parents is still legal in South Africa, and child-beating has significant links to the cycle of gender-based violence that continues into adulthood.116 Boys who experience or witness domestic violence as children are more likely to hold inequitable gender attitudes as adults. The beating of young girls is linked with a higher prevalence of later victimization at the hands of a partner or family member.117

Physical abuse in the home causes problems for children beyond physical harm and future risks; children who witness violence against their mothers are more likely to struggle with PTSD, poor school performance, and later emotional and behavioral problems.118 One study showed that 35%–45% of South African children had witnessed their mothers being beaten, indicating that nearly half of the nation’s children are at risk for these mental health issues that follow domestic violence.119 In addition to high rates of domestic and physical abuse against children, South Africa’s estimated child homicide rate for 2009 was 5.5 per 100,000 people, roughly two times the global average.120 While young boys made up a higher percentage of the homicides, the murder of girls was three times more likely to be related to child abuse such as infant neglect or sexual assalt.121

Practices

Educating Men

Case studies conducted in Africa by the University of Oxford indicate that men may be motivated to commit violent acts against women to assert their masculinity when they feel as though there is a gap between their personal masculine experience and the social norms of masculine control.122 The propagation of the "boys will be boys" ideology absolves men of the consequences of such crimes as gender-based violence, but recent United Nations (UN) research indicates that educating men about the negative consequences of hegemonic masculine norms can increase their participation in shifting gender relation paradigms.123

Organizations such as Sonke Gender Justice, based in Cape Town and Johannesburg, South Africa,124 believe that the education of men is critical when it comes to creating systemic change in the sphere of gender equity.125 Sonke is a leader in the field of male education and engagement against gender-based violence. Sonke uses targeted workshops called "One Man Can" (OMC) to increase male engagement in gender issues in communities across South Africa. These workshops happen primarily in the Eastern Cape, the Western Cape, Gauteng, and Mpumalanga provinces, in both rural and urban areas.126 The workshops take a multipronged approach to change, not just changing the individual behaviors of men but redefining entirely what it means to be a South African man.127 Sonke has also helped implement the Men as Partners (MAP) workshop framework, which includes curriculum intended to undermine the systemic ideologies that men are superior and women are subordinate to them. Additionally, the Men as Partners model includes discussion of how gender oppression models racism during the Apartheid era, drawing on South Africa’s rich history of political engagement to frame gender-based violence and other gendered issues as a part of the human rights discourse.128

Men participating in the OMC workshops are given the opportunity to discuss and confront the roles that they play in the landscape of gender-based violence in their own communities and families. Participants are taught about the pervasive repercussions of South Africa’s gender-based violence problem, learning not only how it affects all of the women in their lives, but also how it affects them as men. In the areas where workshops are held, the attendees are screened for possible participation in a Community Action Team (CAT). Sonke CATs are formed with the purpose of becoming the "eyes and ears" in their communities, encouraging people to report gender-based crimes and recruiting a larger audience of community members to participate in events and training about gender-based violence.129

Impact

In 2019, 3,338 men participated in Sonke OMC workshops.130 Research conducted by the South African Men As Partners (MAP) network showed that workshops such as OMC and MAP that are focused on changing the role of men in South African society are quite effective; 71% of men who had participated in workshops like Sonke’s believed that women should have the same rights as men, while only 25% of men who had not participated held the same opinion.131 Post-workshop, 82% of men interviewed agreed that it was not normal to beat their wives, as opposed to 38% of non-participants.132

Additional interviews indicated that before the MAP workshop, 57% of men thought that when a woman says "no" to sex, sometimes she does not mean it. In follow-up communication three months post-workshop, only 41% of men thought this. Only 61% of these same men disagreed with the statement that women who dress sexy want to be raped, but after participating in the workshop, 82% of them disagreed strongly with the statement.133

Gaps

Sonke’s model has proven effective in changing the attitudes and behaviors of individual men, but the systemic change that it seeks is difficult to measure. Despite the effectiveness of the program, not all of the men participating in the program change their views. Additionally, there is little data collected on whether or not the men who go through the workshops were perpetrators of gender-based violence prior to the intervention. As a result, it is difficult to measure whether changing the attitudes of men through workshops actually prevents prior offenders from committing gender-based violent crimes in the future. Stats reported are also not exclusive to Sonke, making it difficult to ascertain how effective their specific interventions are.

Supporting Victims

For women who have been victims of gender-based violence, emotional and physical trauma is almost certain. However, South African women are unlikely to seek medical and psychological help after a traumatic violent event; as few as 16% of female victims of sexual assault seek health services after being attacked.134 This has been attributed to a variety of factors, including shame, self or victim blaming,135 and physical barriers such as location and lack of transportation.136 South Africa recently instituted the Integrated Victim Empowerment Policy (VEP), which focuses on a more holistic view of the emotional, social, physical, and financial harm that gender-based violence inflicts on all members of the community, including families, victims, and perpetrators.137 In a study conducted by faculty at the University of Pretoria, it was found that empowering victims and acknowledging the many ways in which sexual violence affects their lives are effective tools to reduce crime, fulfill victim needs, and aid in community involvement.138

One way that victims of gender-based violence can be empowered is through encouraging them to speak up about their lived experiences. Khulisa Social Solutions, a non-profit based in South Africa, provides support group help to women who have experienced gender-based violence or sexual assault. Khulisa’s SHINE group therapy program trains peer mentors and facilitators who have experienced sexual assault themselves to lead groups of women toward sharing their experiences. The ideology of SHINE centers around post-traumatic growth or the personal development can be born of trauma and struggle. Women participating in SHINE are led to create a narrative of their assault through a process of dynamic storytelling, which allows them to process their trauma through a lens of personal growth and change. Women are also given the opportunity to speak to offenders during facilitated impact panels.139

Impact

Fairly little impact data is available from the SHINE program, but outcome data is available. In an assessment of the SHINE program in 2015, the following qualitative results were reported from women who had participated: "a greater appreciation of their lives, changed sense of priorities, warmer and more intimate relationships, a greater sense of personal strength, and recognition of new [opportunities]."140 No quantitative data was collected on the women who participated in the SHINE program, making it very difficult to determine the effectiveness of the program.

Gaps

Encouraging victims of sexual assault byoffering legal services to the women who participate in the SHINE program could be an effective means of strengthening the scope of this intervention. While victim support and aftercare are important, programs like SHINE treat a symptom of gender-based violence and not the actual problem. Rather than focusing on prevention of gender-based violence and systemic change to prevent continued violence, resources are allocated to the empowerment of women who have already experienced the problem. Additionally, this program is only helpful to those who are able to regularly attend meetings and make connections with other victims; financial, geographical, and familial barriers may prevent women in different areas of South Africa from getting help.

Monitoring the Activity and Effectiveness of Government Entities

The government of South Africa has instituted sweeping legislation regarding gender-based violence, but a lack of implementation renders these policies ineffective. There is a commendable effort being made by the Commission for Gender Equality (CGE) to monitor the policies being produced and ensure that they effectively protect women from gender-based violence.141 However, the majority of the policies that have been implemented by government officials have focused on aftercare and other services for women who have already experienced gender-based violence, rather than focusing on the prevention of violence. Although the inherent value of prevention is easy to understand, there are very few efforts made to allocate resources, expand interventions that ensure efficacious practices, or develop multi-pronged best practice approaches in different sectors.142

The Commission for Gender Equality Monitoring Project, headed up by Sonke Gender Justice and The Women’s Legal Centre, is a coalition of women’s rights groups interested in monitoring the CGE in order to determine whether the commission is effectively fulfilling its mandate. In Sonke’s 2012 annual report, the CGE Monitor was summarized as being "committed to making sure that South Africa’s impressive gender equality architecture delivers on its obligation to achieve human rights for all.”143

The CGE Monitor takes significant social routes to create dialogue with the CGE when underperformance of the commission is observed. One of the most widely utilized tools by the Monitor is that of the media. Investigative pieces, radio talk show bites, and television appearances by CGE Monitor members have all been used.144 In addition to the traditional media, social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and mass text messages are also heavily utilized by the CGE Monitor,145 particularly by the Women’s Legal Centre.146 Public dialogue and citizen input are a critical part of the CGE Monitor’s model. Public forums have been held frequently since the creation of the coalition in 2012, and individual citizen complaints and feedback about the CGE are processed and taken into consideration by the Monitor to be used in the case of CGE underperformance.147 The Monitor also writes complaints to the CGE and forms special teams of lawyers to aid victims in their legal cases of gender-based violence.148

Impact

Anecdotally, the CGE Monitor has produced fruitful results through its direct pressure on the CGE, but a lack of available quantitative impact data remains an issue. For example, in 2012, the CGE failed to weigh in on a Traditional Courts Bill (TCB), despite the fact that the bill greatly compromised the autonomy of rural women. Several days after the CGE Monitor took to the media, the CGE made oral submissions about the concerning women’s rights implications of the TCB.149

In 2014, a similar situation occurred when 27-year-old Sandiswa Mhlawuli was brutally murdered by her ex-boyfriend on the same day the protection order she had been seeking for months finally cleared. Mhlawuli’s ex-boyfriend was allowed to be released without bail despite the evidence that he had murdered her. The CGE Monitor filed a formal complaint with the CGE about the event and the injustice of the situation. The CGE then mobilized a special team of prosecuting attorneys to press the case through the courts system and ensure that Mhlawuli’s murderer would stand trial for his crimes.150

Gaps

While the actions of the CGE Monitor are apparent and anecdotally effective at getting the CGE to utilize its government mandated power, there is little impact data available. The multi-pronged approach of the CGE Monitor is likely the most effective way to produce results from the CGE, but measurement of the individual tactics has not been initiated by either Sonke or the Women’s Legal Centre. Additionally, while the CGE Monitor is effective in individual circumstances and higher-profile cases, it may not provide the bottom-up intervention that is also necessary to prevent further gender-based violence. According to Dr. Valerie Hudson, gender studies researcher and author of the book Sex and World Peace, "Some think to pit top down approaches against bottom up approaches, asserting that one is more effacacious than the other . . . both approaches are necessary and must be used together in a pincer movement to effect lasting change."151

Educating and Empowering Youth

Researchers at the University of California Berkeley note that one of the best ways to "reduce the risk of violence is to empower women and maximize their role in society."152 For example, a study conducted in South Africa showed that economic empowerment intervention could decrease IPV prevalence rates by up to 55%.153 According to the UN, reducing the risk of violence to women through empowerment and social participation prevents more than just individual cases of gender-based violence; peace of the nation state as a whole also increases when women are empowered to participate in society and stand up against gender-based injustices.154

No Means No Worldwide (NMNW) is a global organization with the goal of ending sexual violence against women and children. Using a curriculum framework entitled IMpower, NMNW teaches young girls and boys violence prevention and intervention skills. The curriculum for girls focuses on assertiveness, vocalness, and physical self-defense skills.155 Boys who participate are taught to challenge rape culture and are given instruction on how to prevent or intervene if they witness an event of sexual violence. Lee Paiva, founder of NMNW, notes that only focusing on men or women without involving everyone (including youth) underscores the current systems of inequality and separation.156

In collaboration with the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Implementing Partners program, NMNW adapts their curriculum to each new region where IMpower is rolled out. Both male and female instructors are trained and vetted before being given the resources to implement the curriculum with a group of students. NMNW has also created a network referral program, connecting victims of gender-based violence and sexual assault with medical and mental health professionals.157

Impact

NMNW is heavily involved in research on gender-based violence, and the data supporting their model is strong. In a study by the American Academy of Pediatrics, one cohort of Kenyan youth were given a six class curriculum about empowerment, consent, and de-escalation, while another group was given a general life skills class. The annual sexual assault rates decreased from 17.9 per 100,000 to 11.1 per 100,000 in the group of students given the empowerment curriculum, and there was no significant change in the other group.158 Additionally, the rates of disclosure of sexual assault in the empowerment class group increased significantly, from 56% before the class to 75% after the class. There was no change in disclosure rates in the other group.159

Little impact data is available from NMNW’s specific program, but outcome data is clear. In areas and communities where the IMpower program was implemented, incidence of sexual violence decreased by up to 51% in women who had gone through an empowerment training program.160 Additionally, after taking the class, 74% of male participants that were witnesses to sexual violence reported intervening and stopping the rape from occuring. Over half of the girls that took the NMNW self-defense and empowerment class reported having used the skills that they learned in class to prevent or deter sexual assault incidences from happening to them.161 At baseline, the incidence of sexual assault was 24.6%; after girls were trained the incidence dropped to 9.2%.162

Gaps

NMNW has an effective program for empowering young women and men to use their voices against sexual assault, but there may be room for improvement when it comes to taking a multidimensional approach to the issue. Some missing aspects may include the types of legal services and advocacy that Sonke and the Women’s Legal Centre are providing. The impact data provided by NMNW is focused on other studies of similar curricula rather than their specific program. In order to ensure that the program is actually impactful, data would need to be collected on groups of youth that participated specifically in the NMNW program. Additionally, much like the SHINE program, young men and women may be unable to participate in the workshops because of a variety of social and practical barriers.

Preferred Citation: George, Lacey. “Gender-Based Violence against Women in South Africa.” Ballard Brief. July 2020. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints