Girls’ Access to Education in Ghana

By Harper Forsgren, Asia Haslam, Shelby Hunt, Andrew Wirkus, and Nathan Heim

Published Fall 2019

Special thanks to Shelby Hunt for editing and research contributions

+ Summary

Lack of access to education negatively impacts a person’s development in a number of ways and leads to fewer opportunities and increased risks for the individual. Females are disproportionately affected by the lack of gender equality in Ghana’s educational system. This inequality comes as a result of practices such as child marriage, child labor, inadequate training of teachers, the inability to accommodate for girls’ menstruation cycles at school, and hidden costs of sending children to school. All of these factors are confounded by social norms that tend to see female education as less valuable and thus more disposable than male education. Lack of access to education for girls leads to negative economic and health consequences, such as increased poverty rates, decreased contraceptive use, increased risk during pregnancy, and threats to the health of children, when their mothers are uneducated. Organizations have worked to fight this issue by increasing girls’ access to sanitary products, creating social support networks to encourage women and girls to continue their educational pursuits, and reducing the costs of education in special schools to make them more accessible. These practices have had varying effects on girls’ access to education in Ghana.

+ Key Takeaways

+ Key Terms

Gender Parity - Equal opportunities for males and females.

Maternal Mortality - “Death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy.”1

Primary Education - Education “focused on establishing the fundamental literacy and numeracy skills of children.”2 Usually children around ages 5-14 attend primary school.

Hemorrhaging - The abnormal flow of blood from a vessel either inside the body or outside the body.

Eclampsia - “A rare but serious condition where high blood pressure results in seizures during pregnancy.”3 Eclampsia is a severe complication of the more common condition preeclampsia.

Context

Education is a vital part of society. It yields important economic developments, higher incomes, and greater equality. Education also promotes individual empowerment and freedom. However, not everyone has access to the benefits that an education provides. In Ghana, a variety of cultural and economic factors make access to education difficult for girls. When it comes to educational reform, Ghana is often considered a role model for the sub-Saharan region in Africa, an area where both education accessibility and education outcomes face many barriers. Over recent decades, the Ghanaian government has implemented many institutional changes in an attempt to improve education accessibility in Ghana. For example, the Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) program, which offers free primary education, was introduced in 1995.4 This program later extended to both junior high schools and senior high schools. Additionally, in an attempt to address the disparity in educational attainment between boys and girls, the Ministry of Education established the Girls’ Education Unit in 1997 as part of the Ghana Education Service.5

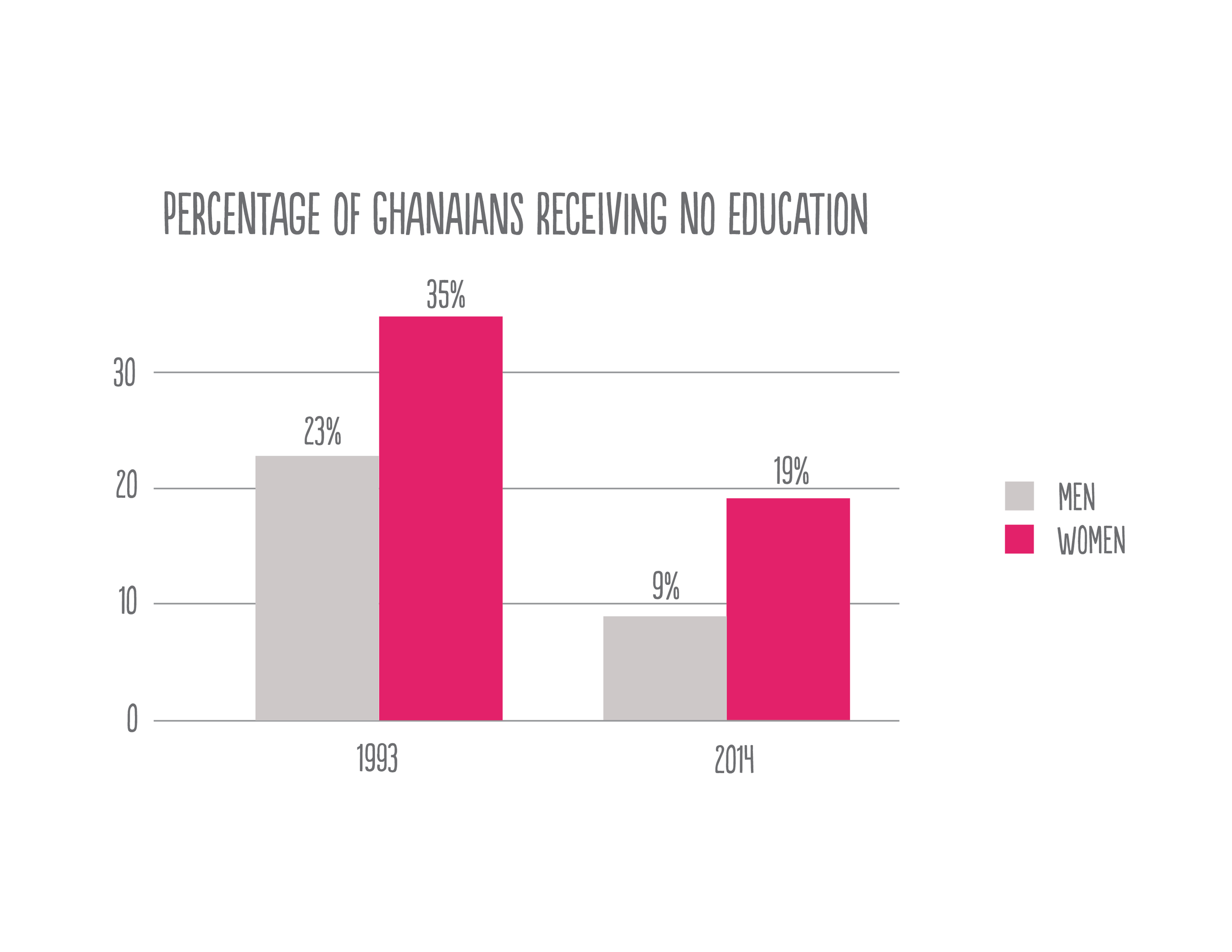

As a result of this widespread education reform, there has been noticeable progress in terms of academic enrollment and achievement. In 1993, 35% of women and 23% of men aged 15-45 reported receiving no education,6 whereas just 19% of women and 9% of men aged 15-45 reported receiving no education in 2014.7 While there appears to be near gender parity according to gender enrollment rates, a deeper look into the true state of education in Ghana reveals that girls still face a disproportionate amount of barriers when it comes to accessing education. The National Development Planning Commission (NDPC) and the United Nations in Ghana suggest that the disparity in completion rates between girls and boys remains, with rates at 89.3% for boys and 84.3% for girls in 2012, though official estimates vary greatly depending on source and data collection methods. This difference in completion rate increases with education level, as attendance rates tend to decrease and dropout rates increase for students as they get older.8

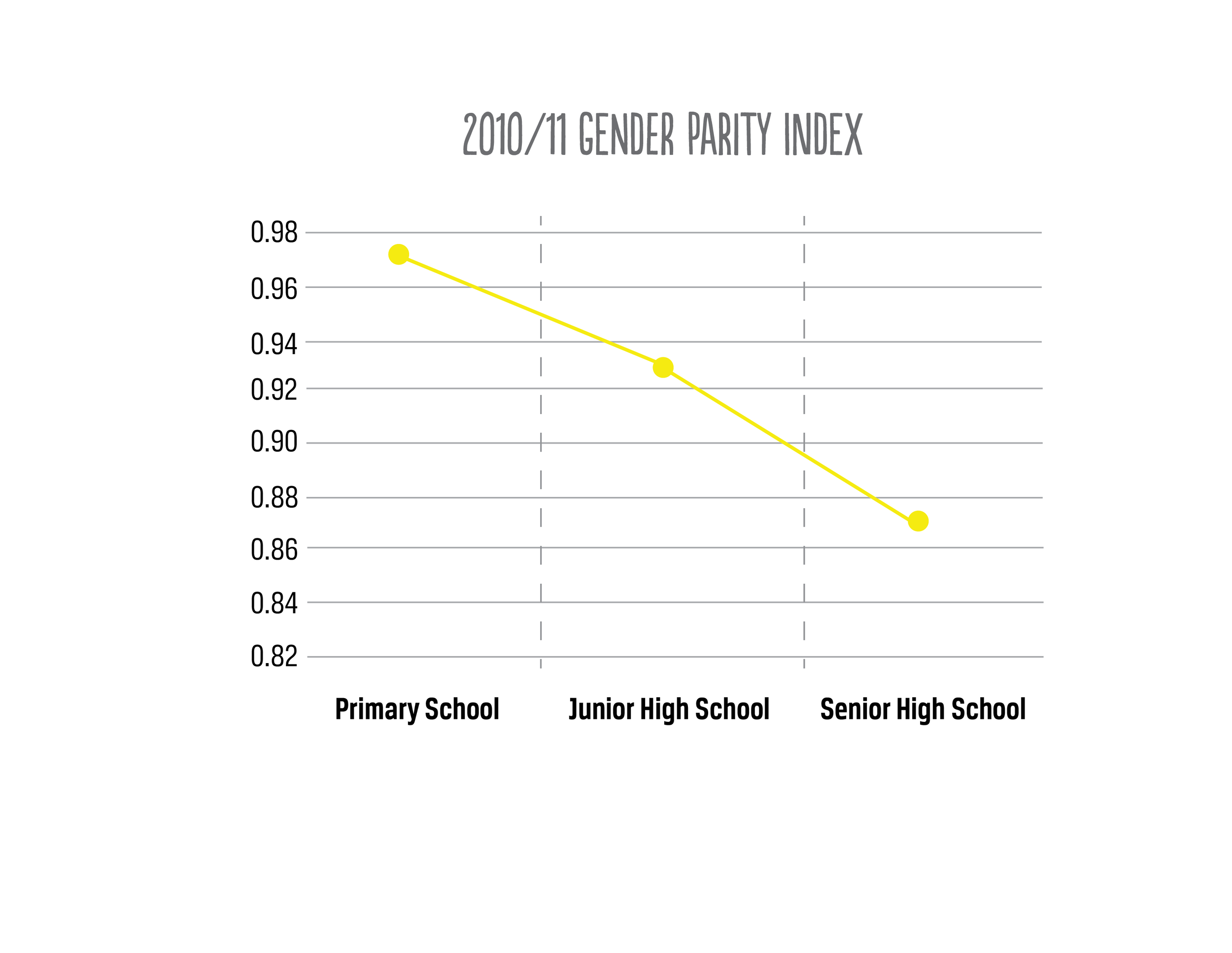

Gender gaps widen as students progress through each stage of school. Enrollment rates in the later stages of schooling better illustrate the gender disparity that exists in Ghana. While enrollment rates in primary and junior high schools appear to have virtual gender parity, the estimated national gender ratio for completion of senior high school is 68 girls to every 100 boys.9 Overall, the probability that children drop out of school increases with age, with the increase being higher for girls than boys.10 As seen in figure 2, gender parity in enrollment decreases as students progress through the later stages of school. This trend is largely attributed to an increase in female dropout rates at a higher rate than those of their male counterparts.11

Additionally, country averages tend to mask the regional disparity that exists between Northern Ghana, which is a predominantly rural area, and Southern Ghana, which has experienced rapid urbanization. On average, girls from rural, more northern regions in Ghana tend to face more barriers to accessing an education than their male or southern-dwelling female counterparts.12 Education attainment for urban men is almost 50% more than for rural women, and in certain parts of the Northern region, the education attainment of men is approximately 0.9 years and for women may be as low as 0.1 years.13 This discrepancy illustrates that there are many factors that influence educational attainment in Ghana, including geographic location and gender. This brief will primarily focus on the role gender plays in access to education in Ghana, but it is important to note that statistics will vary from region to region.

Contributing Factors

Child Marriage

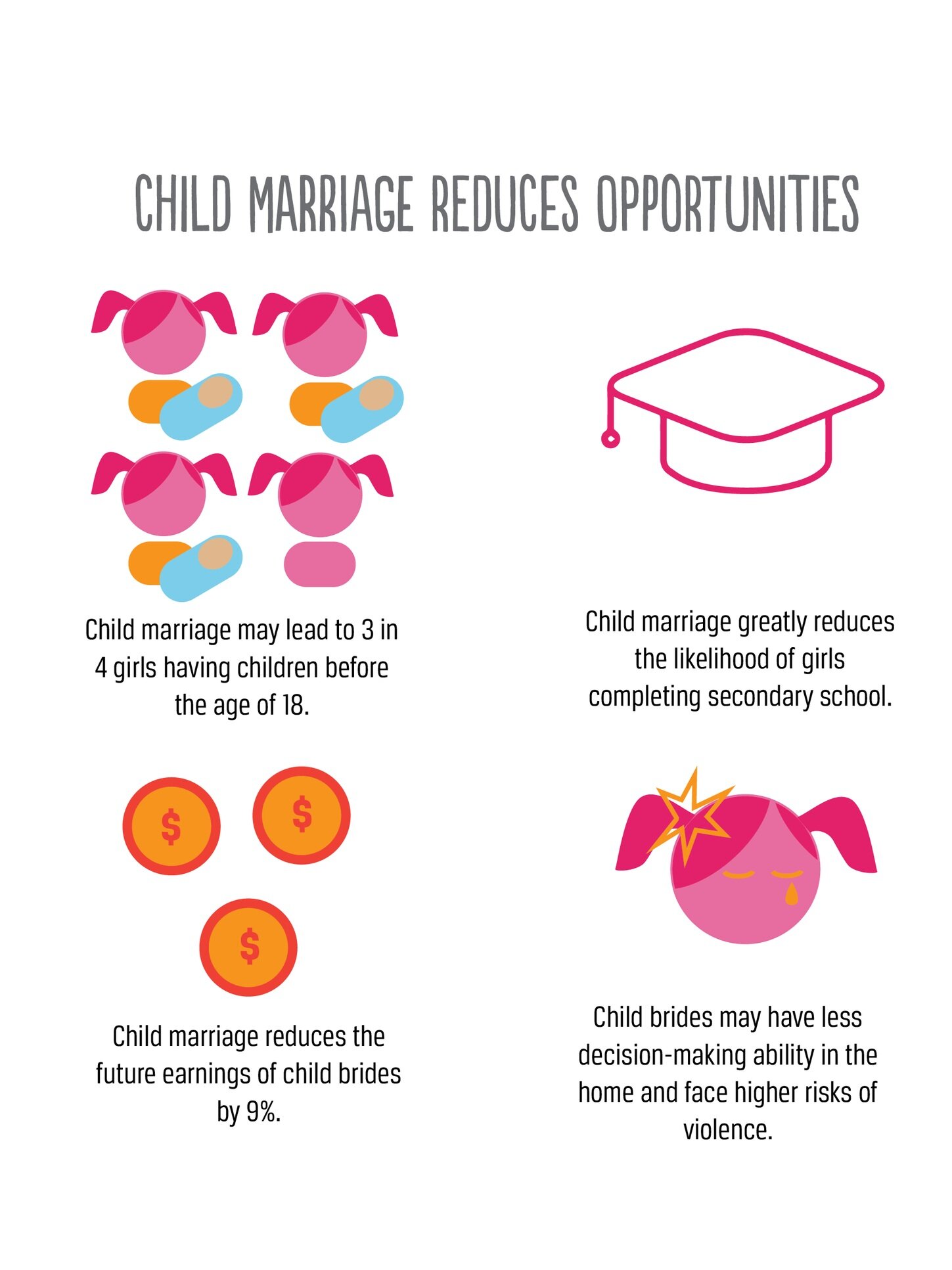

One factor influencing female education in Ghana is the continued practice of child marriage in the country. Child marriage was outlawed in Ghana through the Children’s Act of 1998, which set the legal age of marriage and cohabitation for unmarried couples at 18.14 However, the practice continues to be fairly common, and is linked with a host of negative outcomes affecting children’s physical, mental, social, and emotional development.15 Girls are disproportionately affected by child marriage, with one study reporting that as of 2018, 20% of Ghanaian women were married before the age of 18, compared to 2.3% of Ghanaian men.16

A traditional view of female sexuality is one of the main factors contributing to the high rates of child marriage in girls. In Ghana, as in many African cultures, the honor of a family is greatly influenced by the purity of their daughters. Once a girl begins to mature physically or express interest in boys, she may be seen as a risk to the family, as premarital sex and pregnancy would bring shame to them.17 Child marriage is then seen as a way to eliminate those risks as early as possible or repair the damage to a family’s reputation if a pregnancy occurs out of wedlock. Additionally, child marriage may be implemented as an attempt to protect girls from sexual assault and rape.18 In these cases, families may see this practice as a better option for their child’s future than the alternative.

The decision to marry off a young daughter could be financially motivated as well, as the act frees up resources to help provide for the rest of the family. In many African cultures the groom is expected to pay a bride price, or an offering of money, goods, or services, to the family of the bride. This sum may compel those in need of these goods, specifically those in poverty, to marry their daughters off early. This link between child marriage and poverty is significant, as shown by the fact that girls who are from the poorest 20% of households are 10 times more likely to be married before the age of 18 than girls from the richest 10% of households.19 Though some girls desire the prestige and status of adulthood that come from marrying young, early marriage for those in poverty is more likely to be implemented against the girl’s will as a means of survival.

Child marriage has a profoundly negative impact on a girl’s educational attainment and economic opportunities. One study reported that of those Ghanaian women married before 18, 41.6% had received no education at all, and only 4.7% had reached secondary school.20 In Africa as a whole, literacy is greatly impacted by the age of marriage, with the literacy rate at 53.7% for women married as adults, opposed to only 29.0% for those married as children.21 In Ghana, it has also been found that for every additional year before 18 that a girl is married, the likelihood of her completing secondary school drops by as much as 10%.22 Early marriages also frequently lead to early childbirth, which further reduces the mother’s chances for education and employment.23

Child Labor

Child labor is another practice that limits access to education, again disproportionately affecting girls. Child labor refers to “all children below 12 years of age working in any economic activities” and “those aged between 12 and 14 engaged in more than light work.”24 Though there may be different cultural ideas of what is classified as child labor, these guidelines indicate that there are many types of domestic and industrial labor that must be considered when discussing how child labor impacts girls’ education.

The often unseen and socially accepted nature of child labor in Ghana makes it difficult to measure, though 2016 estimates indicate that about 25% of children aged 5 to 14 participate in economic activity outside the home.25 While some measurements suggest that rates of child labor are fairly equal between boys and girls, such estimates typically do not include household chores and other work outside of the market.26 When these forms of work are taken into account it is assumed that, on average, girls are much more likely to be engaged in child labor.27 This disparity is even greater among child domestic laborers, who live with and perform household work for another family. As is the case with child labor as a whole, domestic labor is difficult to track, though researchers estimate that 90% of all domestic laborers are girls between the ages of 5 and 17.28 Many consider such work acceptable and even beneficial, as it may prepare girls to perform their traditional roles of giving birth, raising children, and performing work around the home.29 As such, school is often considered less important for girls than for boys, and it may be seen as a waste of resources to educate a daughter that will eventually either stay at home or be married off. Multiple studies have concluded that children who participate in child labor are less likely to be in school, either due to dropping out early or never enrolling to begin with.30 The likelihood of a child dropping out to enter the workforce increases with age, as their higher potential earnings are often considered more attractive than continued education.31 In this regard girls are again disproportionately affected, as it is much more likely for older girls to drop out than for older boys.32

Untrained Teachers

Inadequate government planning and policy execution has led to an increase in the number of untrained teachers in classrooms, and high levels of teacher absenteeism has contributed to a poor education quality and diminished access to education in the country. These problems are amplified by Ghana’s rapidly growing population, which has increased from 7.5 million in 1960 to roughly 30 million people in 2018 and is projected to continue growing.33, 34 To be considered a “trained teacher” in Ghana, one must complete a 3 year preservice program and earn a Diploma in Basic Education (DBE).35 The percentage of trained teachers in schools has dropped from 72% in 1999 to 55% in 2017 due to the influx of students coming into schools and an inability for enough teachers to complete the required training in time to match the growing student population.36, 37 To compensate for the lack of trained teachers, volunteers or student teachers are sent into classrooms to teach.

The prevalence of untrained teachers is often greater in poorer, rural, and northern regions, directly contributing to lower student performance. Underperformance of students is often due to multiple intersecting factors, not solely the number of untrained teachers, but it is assumed that this lowering quality of education leads to decreased enrollment and attendance, and increased dropout rates.

Another growing barrier to academic accessibility in Ghana is the high rate of teacher absenteeism, something that directly contributes to higher rates of student absenteeism and dropout rates. On average, teachers in Ghana are absent an estimated 54 days within an academic year of approximately 200 days, averaging 27% annually.38 Additionally, teachers often arrive late or leave early. This absenteeism directly impacts student attendance and student dropout rates because students are less likely to attend school regularly if their teacher is not there.

These factors influence the education and dropout rates of both boys and girls in Ghana. However, though this situation affects both genders, it may be amplified when combined with other female-specific compounding factors, such as societal gender norms or menstrual hygiene management, to create an especially negative impact on girls’ educational attainment and enrollment rates.

Menstrual Hygiene Management

Due to an inadequate distribution of funds and poor government management, many school buildings, especially in rural and northern communities, lack adequate infrastructure to meet the academic and physical needs of their students. One of the greatest infrastructural inadequacies is a lack of proper sanitation facilities and toilets. UNICEF estimates that only 2 of 5 schools in Ghana have toilets or pit latrines and running water. As a result, children often miss classes because they have to leave to find a toilet.39 Girls are disproportionately affected by this issue, specifically during menstruation. The absence of proper facilities makes maintaining proper hygiene impossible, and girls often choose to stay home from school for the duration of their period to avoid embarrassment and infection. As a result, girls in Ghana miss approximately 30 to 50 school days each calendar year, leading many to fall behind and choose to drop out of classes.40 These absences contribute greatly to the dropout rate, which increases for girls as they get older.

Another issue that affects girls’ ability to attend schools is the lack of access to menstrual products. A study of female university students in Ghana found that 36.9% of the participants reported that menstruating negatively impacted their schooling. These students said that the greatest concern when they began menstruating was discomfort, followed by stains on their uniforms, difficulty concentrating in class, and missing school.41 The same students reported that when they first began menstruating, 78.2% of them used sanitary pads, but 19.4% of them used toilet tissue or reusable cloth. The lack of sanitary products may lead some girls to choose to stay at home rather than deal with discomfort or embarrassment that comes from menstruating without proper hygiene products in the school setting. It is important to note that researchers conducted this study using a sample group containing only university students. Therefore, actual rates of sanitary pad usage are likely much lower, considering the fact that university students come from a higher social class than average Ghanaians. In this group, a majority of the students responded that they were in the middle social class at the time of their first menstruation.42 Accurate data on the effects of menstruation on school attendance in Ghana are very difficult to come by, partly due to the fact that menstruation is a very under-researched issue.

The Hidden Cost of Education

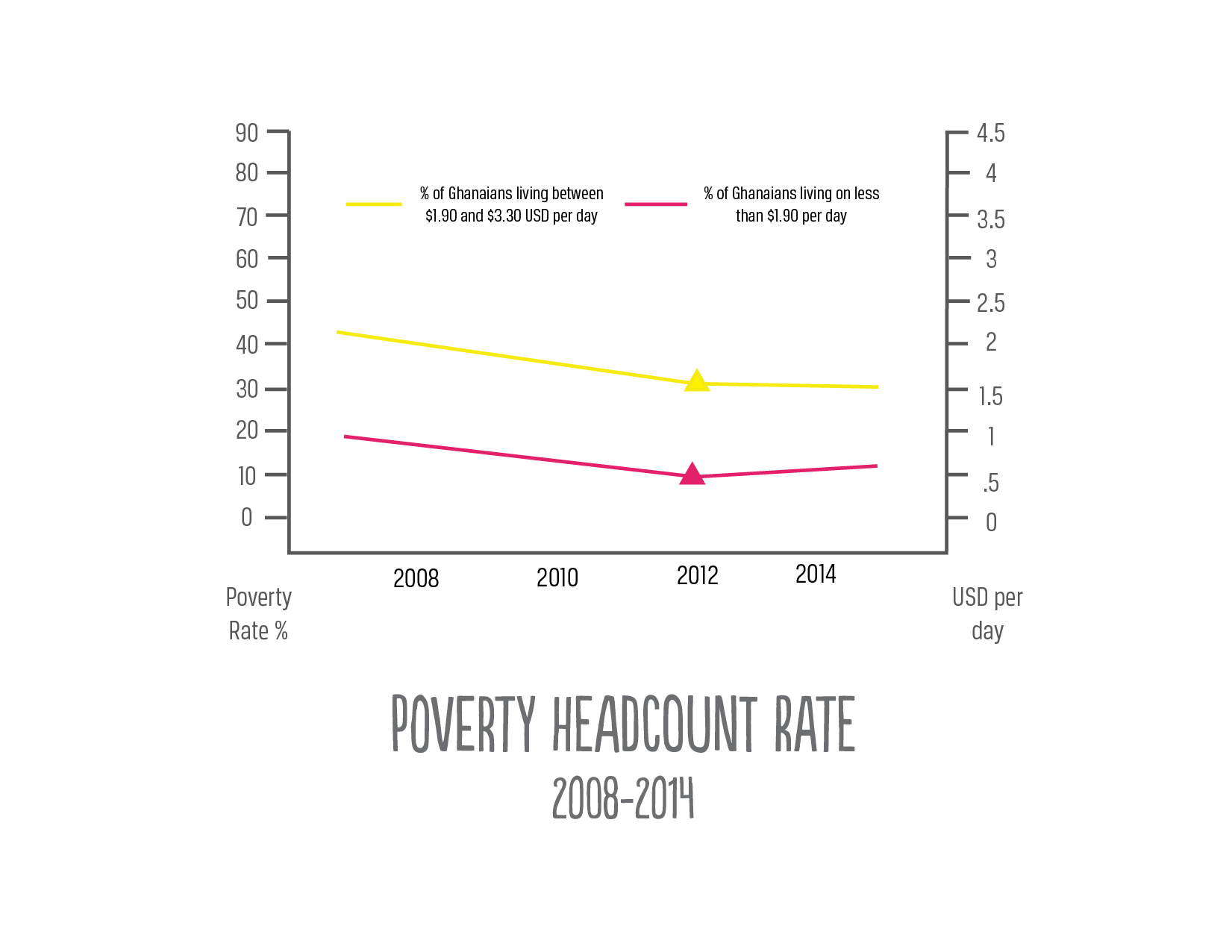

Another factor that contributes to the amount and quality of female education in Ghana is the cost of attending school. This cost is especially prevalent for girls who come from impoverished circumstances, because those in poverty often lack the resources to spend money on anything other than their most basic needs. In 2012, the most recent year of measurement, roughly 12% of Ghanaians lived in extreme poverty (on less than $1.90 USD per day), and 32.5% of Ghanaians lived on an amount between $1.90 and $3.30 USD per day.43

Though the Ghanaian government made a vow to make school attendance free (including uniforms, library fees, books, etc.), insufficient and untimely government funding has made it so many schools, especially those in rural areas, do not have the budgets to provide the free schooling that was promised.44 In 2015, researchers estimated that even in “fee-free” public schools the average household cost per pupil per year is 793GHC, or $168.37 USD.45 Some of the most common hidden fees, besides a payment for tuition, are “food, uniforms/sports clothes, textbooks, exam fees, mandatory extra classes and parent teacher associations.”46 Teachers report additional hidden school costs, noting that some of their poorest students are unable to attend school because of an inability to afford one or more of the following: school uniforms, shoes, transportation, or food.47

Consequences

Economic

Lack of access to education is not only caused by poverty, but it also contributes to and furthers the poverty cycle. Women are more susceptible to poverty and experience it at more severe levels than men do.48 Women’s unique vulnerability to poverty is closely tied with lack of education which, in conjunction with other social and cultural factors, restricts women’s access to capital and reduces the number of marketable skills women can provide. Low literacy in particular limits women’s economic mobility within Ghanaian society and markets. By restricting girls’ access to schooling, women are systematically relegated to the lowest-return areas of the informal economy, making poverty both a cause and effect of gender disparity in education.49

In Ghana’s rural regions, where there are much lower rates of education for girls, women are more likely to experience economic difficulty. Women in these areas have less access to or control over land and capital, which is evidenced by the fact that men own 3.2 times more farms than women do in Ghana.50 In Ghana as a whole, only 9% of employed women earn consistent wages as compared to 28% of employed men.51 This disparity spikes in rural Ghana, where men are a full 5 times more likely to earn a consistent wage than women.52 Within the agricultural sector, women in Ghana are traditionally responsible for food crops rather than cash crops, and according to the Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy, food crops is the category most often affected by severe poverty.53

Health

Lack of access to education for girls results in serious, lifelong health consequences for girls and their future children, should they have them. Women who are educated about safe sex, proper pregnancy practices, and delivery care in schools or other educational facilities have better health outcomes than women who do not have the same levels of education.54 When women are educated both infant and maternal mortality rates tend to decrease.55

Contraceptive Use

Sexual education in Ghana occurs in both primary and secondary schools, which then indicates that those who do not attend these schools may not receive the same quality of sex education.56 Knowledge about contraceptives can protect women from STIs and enable informed choices about family size, but because so many women in Ghana are not currently educated, they cannot make informed decisions regarding family planning. On average, girls with more schooling, especially those with secondary or higher education, tend to seek out better methods of birth control which ultimately gives them the ability to plan their families more purposefully. In a study collected by the Demographic Health Survey for 14 Sub-Saharan countries, all found that “an increase in female education is significantly associated with an increase in current contraceptive use.”57 If girls stay in school longer, they are more likely to be educated about contraceptives and birth control methods and therefore have better health outcomes.

Risk During Pregnancy

A woman’s educational attainment also impacts her risk during pregnancy and childbirth. Women and girls who have more education tend to seek out medical care when pregnant more often than those their age without the same level of education.58 A 2013 study found that 2 of the top 3 causes of maternal mortality in Ghana are hemorrhaging and eclampsia; both of these birth complications are preventable with proper medical attention.59

In 2015, Ghana had an average of 319 maternal deaths to 100,000 births,60 compared to the world average of 216 per 100,000 births,61 and 12 per 100,000 births in the most developed countries of the world.62 The second leading cause of maternal mortality in Ghana is complications with abortions, both medical and private, with much higher rates of mortality among those who did not seek out medical assistance.63 Women without education are much more likely to try to perform abortions on themselves at home, the riskiest type of abortion, than any other sub-group of women.64 Research suggests that if more women had access to education, the maternal mortality rate could be significantly reduced.65

Health of Children

One of the largest factors for predicting health outcomes of a child is the level of education attained by the mother.66 On average, educated mothers are more likely to seek help from skilled birth attendants, which reduces the risk of delivery complications that pose risks to the child.67 There is also a correlation between a mother’s education and her ability to provide basic sanitation and hygiene for her child.68 Ghana’s leading causes of childhood mortality are diarrheal diseases, nutrient deficiencies, and common infectious diseases, all of which are preventable with the proper education of sanitary practices.69 When girls do not receive an education about modern health practices, it perpetuates a cycle in which mortality rates are high among both child and mother.

Practices

Sanitary Interventions

Sanitation is a concern in countries like Ghana, where many girls have difficulty attaining sanitary products once they begin menstruating. Additionally, schools in the peri-urban and rural regions of Ghana still mostly use pit latrines and do not have separate facilities for boys and girls.70 For this reason, it is often impossible for young girls to go to school when they are on their period. There are many organizations who recognize how inadequate sanitation affects girls’ chances of attending schools and are working hard to make changes that will make it easier to purchase menstrual products as well as improve sanitation elsewhere. The Ghana Education Service (GES) created an initiative promoting menstrual hygiene management (MHM) through education on menstruation, providing sanitary products when needed, and promoting personal hygiene.71 The World Bank advocates for the implementation of the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area Sanitation & Water Project that is aimed to improve education on the MHM initiative, provide sanitary menstrual products, and give girls access to clean and private water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) facilities.72 GES has also partnered with the Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection to advocate for a change in policy that will remove the 20 cent tax on menstrual hygiene products,73 and UNICEF has taken action to encourage menstrual hygiene education for young girls in Ghana.74

Impact

Research done in Ghana has shown that, especially in rural schools where absenteeism is the highest for menstrual-related concerns, providing girls with education about their period, as well as sanitary materials, could increase the rates of school attendance significantly (from 80% to 92%).75 In addition to more frequent school attendance, girls who participated in the education aspect of this intervention reported significantly less feelings of shame, lack of confidence, insecurity, and inability to concentrate while at school.76 Simply providing education to a young woman about her period and how to manage it at school greatly increased that girl’s likelihood to attend school on the days during her period.77

Gaps

While sanitary pads and education do help significantly in girls’ ability to access education, single gender bathrooms, the pressure to use unfamiliar products, and cultural stigmas all still inhibit them from achieving full access to the education system.78 Aside from access to sanitary pads, evaluation of improved infrastructure allowing girls to have a place to take care of their menstrual needs has not been performed.79 Most people believe that it could have a serious impact on girl’s education and their decision to attend, and while studies have proven a variety of health benefits, no analysis has been done about the resulting attendance of girls with access to better facilities.80, 81 A lack of bathroom facilities inhibits the effectiveness of pad-related interventions since the girls will often feel self conscious about leaks, the smell, and the mess, because they do not have a proper way to clean themselves or their pad.82 There also have not been any studies determining the effectiveness of menstrual cups, which are a fairly new sanitary intervention. Additionally, research by the World Bank suggests that “girls’ self-efficacy to manage their menstruation and engage in school may be dependent on their attitude about the sanitation interventions provided in the school.”83 In other words, even if interventions are successfully provided by organizations, girls may not take advantage of them because they feel uncomfortable with them.

Social Support and Networking

Some girls are unable to go to school because they lack financial and social support. As stated earlier, girls’ education can be seen by some as less valuable than boys’ education, and therefore more expendable. There are initiatives being implemented in the rural parts of Ghana that provide a sort of “networking” experience, providing links between organizations funding girls’ education and students, families, schools, and services through counsel and support.84 Organizations such as Campaign for Female Education (CAMFED) Ghana work to provide funding and support for at-risk girls and its alumni organization, the Campaign for Female Education Alumnae Association (CAMA) is a networking tool in which those that have graduated due to the CAMFED program stand as “Learner Guides” who act as mentors and support systems for current students.85

Impact

CAMFED and CAMA are organizations that are not only established in Ghana, but in neighboring countries in Africa such as Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Because of their wide range, most of the impacts that can be found span all 5 of these countries and are not completely focused on Ghana. This fact being acknowledged, CAMFED and CAMA’s initiatives have made it so 90% of girls enrolled in the program remain in and complete school.86 Additionally, an estimated 836,120 students have been helped in these 5 countries by CAMFED’s Safety Net Fund, which covers the costs of books, school clothing, and other supplies that students are unable to afford.87 This program minimizes the rates of dropout by students that do so because they cannot afford to go to school.

Gaps

While CAMFED, CAMA, and other similar organizations are able to fund many students on their educational journey, it is also difficult to know if the raised rate of student enrollment and completion of school is directly due to these programs or a mere correlation. Additionally, it is stated that CAMA has trained over 12,000 alumni to be mentors for current students,88 but it is difficult to know whether or not these alumni support systems play any role in keeping the students in schools without quantitative data to back it up.

Low-Cost Private Schools

As stated earlier, a large problem that keeps girls from attending schools is the financial cost, particularly for girls whose families live in poverty. The low-cost private school initiative is supported by the Center for Education Initiatives (CEI), and is aimed to provide cost-effective, quality education for a low cost.89 These schools, known as “Omega Schools,” charge a daily price for attendance which is said to be much more manageable for families than an upfront monthly charge, and extend the school day to 7 hours instead of the 4 hours typical for most schools in Ghana.90 The goal is to lower the upfront costs of education, provide incentives for students to attend school, and then to make the time spent in school as beneficial as possible.

Impact

Omega Schools opened over 20 schools from 2009 to 2013, and enrollment grew from 4,417 students to 11,596 students from 2011 to 2013.91 Currently, there are 38 of these low-cost schools in rural Ghana educating over 20,000 students, and 51% of these students are girls.92 Omega Schools have also been reported to reduce the cost of annual fees for students, with a 2013 report stating that they cost an average of $113 per student per year compared to the $166 average cost of public schools in Ghana.93 CEI is currently tracking internal factors such as enrollments and test scores, but the impact evaluation has not been released due to the fact that the organization is still in the data-collection phase.

Gaps

Omega Schools have been criticized by some who state that the low-cost private school model does not benefit the poorest population due to the fact that there is still a daily charge that many in severe poverty would be unable to pay.94 It is also interesting to note that, though these schools have existed for about 10 years, there is not much impact evaluation concerning whether they have truly benefited the communities they committed to serve. This lack of impact evaluation and criticism from researchers about the program leads many to wonder if this practice is effective at providing students, especially girls, with a quality education.

Preferred Citation: Forsgren, Harper, Asia Haslam, Shelby Hunt, Andrew Wirkus, and Nathan Heim. “Girls’ Access to Education in Ghana.” Ballard Brief. October 2019. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints