Inadequate Resettlement of Refugees in the Southern European Union

By Jenna Vasquez

Published Summer 2021

Special thanks to Lorin Utsch for editing and research contributions

Summary+

The European Union (EU) and specifically the countries in southern Europe have experienced an unprecedented number of refugees entering its countries since the Syrian Civil War began in 2011. The resettlement of these refugees has been inadequate due to a number of factors, and there are many bureaucratic obstacles to refugees applying for asylum in an EU country. Additionally, countries simply lack space, resources, and legal staff to handle the influx of newcomers. These factors lead to a variety of negative consequences for the refugees and the host countries, including violence among refugees and law enforcement and financial insecurities and poor living conditions for refugees. Several organizations have intervened in order to improve the refugee resettlement process in Europe, doing things such as revolutionizing the design of refugee camps, providing refugees with an economic identity and footprint, providing temporary host families for refugees, and providing specialized instruction and skills training to the refugees.

Key Takeaways+

Key Terms+

Asylum—The protection granted by a nation to someone who has left his or her native country as a political refugee.1

European Commission—The European Union's politically independent executive arm. It promotes the general interest of the EU by proposing and enforcing legislation as well as by implementing policies and the EU budget.2

European Union (EU)—An international organization comprising 27 European countries and governing common economic, social, and security policies.

Refugee—According to a definition provided by the European Union (EU), individuals must fit the following criteria to be considered refugees: 1) they are not from the EU country in which they are currently staying nor are they from any other member states of the EU; 2) they have left their country of origin, due to a “well-founded fear of persecution;” and 3) they either cannot or will not go back to their country of origin, due to such fear.3

Refugee Camp—Temporary facilities built to provide immediate protection and assistance to people who have been forced to flee their homes due to war, persecution, or violence. While camps are not established to provide permanent solutions, they offer a safe haven for refugees and meet their most basic needs—such as food, water, shelter, medical treatment and other basic services—during emergencies.4

Resettlement—Transfer from the country where a refugee initially sought protection to a different EU member state where he/she can be granted permanent residence status.5

Southern European Union—In this brief, the countries considered part of the southern EU include Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, the Republic of Cyprus, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain.

Context

In recent years, the European Union (EU) has been a hub of refugee intake and resettlement policy. In the EU, the refugee situation escalated to a “crisis” in 2011, when the Syrian Civil War began.6 This civil war and long-standing violence in nearby countries in the Middle East have been the cause for thousands of people to flee the violence to nearby countries—often passing through Lebanon and Turkey before arriving in Southern Europe, where the EU provides millions of dollars of humanitarian aid in the form of food, shelter, and other resources.7

Refugees come to the southern countries in the EU from a number of places and through a number of routes. Due to the civil war in Syria, over half of Syria’s pre-war population (meaning more than 10 million people out of 21 million)8 were displaced, either within the country or across borders into Lebanon and Turkey. As of 2015, over half of Europe’s refugees traced their origins back to either Syria, Afghanistan, or Iraq.9 Most refugees usually enter the EU through one of three main routes: the Central Mediterranean route (from North Africa to Italy by sea), the Eastern Mediterranean route (from Turkey to Greece, Bulgaria, and Cyprus by land), or the Western Mediterranean route (from North Africa to Spain typically by sea).10

Source: United Nations. “Desperate Journeys. Refugees and Migrants Entering and Crossing Europe via the Mediterranean and Western Balkans Routes.” UNHCR. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.unhcr.org/news/updates/2017/2/58b449f54/desperate-journeys-refugees-migrants-entering-crossing-europe-via-mediterranean.html.

When refugees first arrive in the Southern European Union, they go through a number of steps as outlined by the EU to ensure their safety and rights are maintained as they seek to gain asylum. These steps include registration, fingerprinting, a personal interview, and a medical examination.11 Refugees have the right to free legal assistance in a language they understand during these initial procedures, and member states of the EU must also ensure that refugees have the opportunity to seek legal assistance at their own cost during the asylum-seeking process.12 During these initial processes, member states are required under national law, when possible, to avoid the use of detention centers as a means to house refugees, but there are instances when detention centers are still used to do so,13 as was the case when Greece transferred at least 1,300 new arrivals from its islands to detention sites on the mainland in early 2020.

Border countries in the EU tend to receive higher numbers of refugees. In 2015 alone, 1.8 million migrants crossed the Mediterranean Sea or the Aegean Sea to get to Europe.14 While this number has significantly decreased since 2015 (120,000 in 2017 and just over 60,000 in the first six months of 2018), these lower numbers still exceed the infrastructure in place in southern Europe. Local communities in Italy and Greece respond to urgent needs of refugees who show up on their coasts but ultimately must help many of them relocate to other countries inside or outside the EU.15 The top two countries in Europe that received the most asylum applications in 2015 are Germany (more than 476,000 applications) and Hungary (177,130 applications).16 During this time, the European Commission proposed the relocation of over 100,000 refugees and recommended discussions on a permanent quota system for crisis situations regarding refugees, but this proposal was unsuccessful.17 As the individual EU member states remain fairly divided rather than united in their approach to refugee resettlement, the system remains inadequate and refugees have even been known to turn to self-relocation since no cohesive asylum system exists in the EU.18 For the purposes of this brief, inadequate resettlement is taken to mean that refugees’ process of being resettled is lengthy and inefficient, and that because of this, resettled refugees do not enjoy the same quality of life as their natural-born counterparts in terms of living conditions, employment, and other social factors.

Sources: Timothy Hatton, “Refugees and Asylum Seekers, the Crisis in Europe and the Future of Policy,” Economic Policy 32, no. 91 (January 2017): 447–96, https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eix009.

As refugees have flooded into Europe in unprecedented numbers since 2011, the EU has realized the need for their resettlement, or in other words, their transfer from the country where they initially sought protection (which tends to be the inundated border countries mentioned above) to a different EU member state where they can be granted permanent residence status.19 If and when a refugee is granted this permanent status, he or she is entitled to the following rights: 1) A residence permit valid for three years (and renewable); 2) Documents that enable refugees to travel outside the host country; 3) Access to and equal pay in employment; 4) Education access under the same conditions as nationals; and 5) Social welfare and healthcare.20 While around 10,000 refugees were successfully resettled in the EU by the end of 2014, 1.15 million refugees were still in need of resettlement at that time.21

It should be noted that due to the nature of resettlement being an ongoing and lengthy process, many of the statistics used thus far and that will be used throughout the course of this paper are constantly changing. It is difficult to find exact numbers of refugees/migrants that have actually been permanently resettled in the EU, as they move around, migrate to nations outside the EU, etc. The lack and nature of data contributes to the complexity of this social issue.

Contributing Factors

Administrative Obstacles to Gaining Asylum

The sheer number of refugee applications per year creates administrative complications for the European Union. In 2015, EU countries offered asylum to 292,540 refugees.22 In the same year, more than a million migrants applied for asylum—although many of those who were given refugee status may have applied in previous years because the process often takes more than a year from start to finish.23 This carryover means that less than 30% of refugees who have applied for asylum are actually granted it. Plus, when translation is involved, as is the case in the asylum procedure for many refugees coming to Europe, transcribing what is spoken into a written text can be an especially complex process.24 Each meeting with government or migration officials has the potential to be misunderstood or misrepresented, and sometimes the person creating the transcript omits certain information not deemed necessary,25 which can also slow down the process significantly.

Much of a refugee’s plight to gain asylum is determined by his or her ability to produce the correct documentation; when he or she cannot, the resettlement process is more lengthy and incomplete and can be denied. Refugees may bring photos or letters but do not often bring documentation such as birth certificates or proof of identity in their rush to leave; they also may not bring proof of need for refugee status with them when they unexpectedly leave their country of origin.26 Without such proof in the form of government documents, caseworkers are left with the word of the person as to whether or not they are actually deserving of refugee status.27 This situation can slow down their application process as governments in the EU try to sort through who is there, why they are there, and how to deal with the lack of documentation.

Lack of Adequate Legal Assistance

Refugees often experience inadequate legal assistance when they arrive in a new country, delaying resettlement. Sometimes the lack of legal assistance is due to the fact that there are not enough lawyers available and willing to help the hundreds of thousands of refugees who are in need of help with navigating their documentation, registration, and other legal matters. A protection and advocacy adviser for the Norwegian Refugee Council offers one reason why this is the case: there are almost 3,000 refugees on the Greek island of Chios and only seven lawyers.28 This same adviser is also quoted as saying that “there are very few actors that are supporting the civil documentation process that [refugees] need assistance with.”29 This lack of legal assistance is fairly widespread across the southern countries of the EU—in a 2020 report from the European Asylum Support Office, countries including Spain, Bulgaria, Greece, and Hungary have raised concerns about issues such as lack of adequate facilities for carrying out legal processes to lack of legal aid provided by the government to refugees in detention centers.30 Plus, even if there were enough legal aids to assist refugees, many of these refugees may not even have the means to pay for a lawyer after the initial procedures (where free legal assistance is offered) have passed, as was the case for a refugee’s legal case in 2017 and has been the case for others.31

Lack of Cohesive Asylum Policy

While the EU operates loosely under common regulations, individual countries still maintain their own autonomy, and in the case of refugee resettlement, no standardized asylum policy exists across the EU.32 Each country determines its own willingness to accept refugees, and most have very small, unofficial quotas.33 Although the number of receiving countries in the EU grew from 14 in 2005 to 28 in 2015, most countries only accept between 1,000 and 10,000 refugees, which is less than 10% of the number of refugees who apply every year.34, 35 A number of other factors can determine how many refugees are hosted by each member state, including geographical location, the level of benefits offered in the asylum procedure, and whether or not refugees intend to assimilate to their host country’s culture or remain living in networks of their own ethnicity.36 These factors create a state of disorganization, since each country does it a little differently, that renders the resettlement process inefficient. No cohesive resettlement policy exists in the EU to address this disparity, and without such a policy, countries are left to act on their own accord and decide for themselves how many refugees to accept.37 Some countries such as Germany and Hungary have therefore had to take what they might consider a disproportionate share of refugees.38

Politics among Countries

The ever-changing and often volatile politics among countries, both inside and outside the EU, affect the effectiveness or feasibility of the resettlement process. Especially during times of war or political conflict, some EU countries have restricted their borders to refugees of certain nationalities. For example, the war in Syria intensified in 2015 and ISIS declared war against the West. Because of intense conflict, displacements to Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan surged, and mass movement through Turkey to Greece and on to other EU countries increased as refugees fled violence. This increase was met with border closures and restrictions, initially between Greece and Turkey, and later on between Hungary and Serbia and between Bulgaria and Turkey.39 These closures were likely an effort by EU countries to make sure their own citizens were protected during this volatile time,40 as they navigated their political relationships with Middle Eastern countries. Thus, outside factors that affect a member state’s border policies, procedures, or other political positions also factor into the resettlement process of refugees and often slow it down or render it impossible for a time.

Perhaps one of the most visible policies that contributes to the inadequate refugee resettlement process can be seen in the Dublin Regulation, adopted by the EU in 2003. This regulation allocates refugees and asylum seekers to various European states, “generally placing responsibility [for] resettlement upon the state in which the migrant first entered Europe” (emphasis added).41 This regulation has meant that since around 2015, boatloads of migrants crossing the Mediterranean have stretched resources in border countries Italy and Greece (the main arrival countries for refugees crossing the Mediterranean Sea) to their limits.42 This migratory pattern puts an uneven amount of pressure on countries in the EU that happen to be geographically located where refugees tend to first arrive, usually because they are located on the southern coast or another border of the EU. This uneven weight that southern border countries must carry means that processes toward resettlement are slowed due to capacity limits and other factors mentioned elsewhere in this brief.

Unwillingness of Countries to Accept Refugees

In addition to the obstacles already discussed, refugee resettlement is also hindered by the fact that many countries in the EU simply do not want to accept more refugees. Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia have either refused outright or resisted taking in refugees since the European Commission first pushed through temporary quotas in 2015 as a way to ease the burden on frontline states—mainly Italy and Greece.43 When member states outrightly refuse to take in a share of refugees for resettlement, the number of applications for asylum in other member states increases and therefore, refugees have a harder time getting their applications approved.44 Even France, which has seen at least a 9% increase in refugee acceptance year over year since 2015,45 is still fairly limited in its willingness to accept refugees due to concerns about terrorism and loss of national identity.46 While most countries in the EU have accepted or are accepting refugees to some extent, the countries that do not accept refugees slow down the resettlement process.

Consequences

Poor Living Conditions

Because the process to being fully resettled can often take months or even years, thousands of refugees end up in temporary or permanently inadequate living conditions due to overcrowding or other causes. For example, in France, where over 300,000 refugees were granted asylum in 2017,47 refugees resigned to sleep on the streets in makeshift refugee camps in freezing conditions in Paris.48 A journalist describes one makeshift refugee camp in France as “a sprawling and squalid ‘jungle’ of tents and improvised shelters” where an estimated 5,000–7,000 refugees live. At this makeshift camp, tents are often infested with rats, water sources are contaminated by feces, and the refugees living at the camp have experienced a number of health-related issues such as scabies and tuberculosis.49 This example is not an isolated incident, and similar conditions have been reported in refugee camps in Greece50 and Italy.51 When the Moria refugee camp, one of the biggest refugee camps in Europe, was destroyed by fire in 2020, 13,000 people were left without shelter.52 In the provisional tent camp being used as a temporary replacement to Moria, the living conditions are not sufficient either, and as of October 2020, 8,000 people were living in tents not fit for winter conditions.53 Resettlement camps, whether temporary or permanent, often do not provide adequate living conditions for the hundreds of thousands of refugees in Europe, which inhibits refugees’ abilities to establish a new life in their host country.

Socio-economic Disparities

Refugees in southern Europe, even when physically resettled in their new country, still experience financial insecurity and unemployment at higher rates than other groups; since a refugee is only considered resettled based on the parameters set forth in the context, these disparities indicate that refugees are experiencing inadequate resettlement. For example, it takes roughly 15 years for a refugee in Europe to reach the same employment rate as other migrant groups such as non-refugee immigrants.54 In most countries in the EU, the employment rate is much lower for refugees than it is for EU natives.55 This is especially true for refugee women in the EU, though the rates are still lower for refugee men as well.56

These disparities are not limited to employment rates. In nearly all EU member states, accepted refugees experience a lower standard of living than the native-born population.57 This includes gaps in educational achievements of resettled refugees as well as refugees being at higher risk of social exclusion and poverty.58 For example, in regards to education across Europe in 2015, roughly 3 in 4 native-born students attained the baseline proficiency in science, reading, and mathematics, while only 3 in 5 students from migrant backgrounds achieved these same proficiencies.59 Overall, refugees experience greater levels of socio-economic distress and barriers to achieving a high quality of life, even upon being resettled in a new country. Thus, these refugees’ resettlement process is never quite complete.

Mental Health Struggles

Refugees are subject to a number of factors that put them at more risk of mental health issues than other populations,60 and these risk factors can occur at all stages of the migratory and resettlement process. In fact, even after resettlement, poor socio-economic conditions (another consequence of inadequate resettlement processes) are associated with increased rates of depression among refugees.61 While the range of reported prevalence varies greatly, the prevalence of depression among refugees and migrants in 2018 in Europe ranged from 5% to 44%, while the prevalence among the general European population ranged from 8 to 12%.62 Changes in legal status, residency, and work permit status also make refugees more vulnerable to poor mental health conditions,63 such as post-traumatic stress;64 these changes are all parts of the resettlement process experienced by refugees and thus, mental health issues are more common among refugees due to their already inefficient resettlement process.

Practices

Channel Relevant and Current Information Directly to Refugees

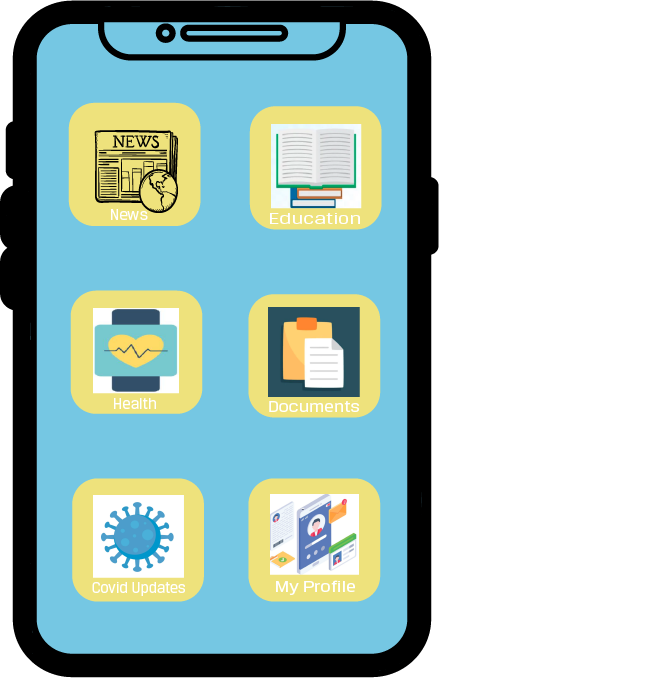

One organization working to provide refugees with the information and resources they need to adequately resettle in Europe is the International Rescue Committee (IRC). This organization uses a website and Facebook page (refugee.info) to provide refugees in Greece and Italy with real-time information and updates in the refugees’ native language about things such as COVID-19 updates and restrictions, documents involved in the asylum process, and education and healthcare options available in the country they are currently in, including mental health institutions that the refugees can access.65 This organization thus addresses a few aspects of the resettlement process all at once, providing resources concerning documentation, mental and physical health care, and real-time updates about COVID-19 which might affect refugees.

Source: “Refugee Info.” refugee.info. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.refugee.info/greece.

Impact

To date, the IRC has assisted over 30,000 refugees in Greece. Its main focuses in the country concern livelihood improvement programs that help refugees learn about and seize self-employment opportunities, as well as receive employment training.66 In Italy, the organization works primarily with education initiatives, both through refugee.info for adults, and through training teachers to provide safe and positive learning environments for refugee children.67 In Germany, the organization also trains teachers working with refugee children and also helps refugees find jobs and start businesses, thus helping them gain financial independence. It also provides mental health support in the form of stress management and coping skills education.68

Gaps

While the IRC provides an overarching number of people help in Greece, we do not know many more specifics about how these refugees’ lives have been impacted. The organization does not even provide such a number for Italy or Germany, so the data from these locations is even more sparse. Since the IRC works all over the world, Europe is not its only focus, and thus, even policies or practices that have been successfully implemented by the IRC elsewhere have not made it to Europe yet.69

Modernize Refugee Camps and Arrival Centers into Functioning “Cities”

As previously mentioned, countries across the European Union simply do not have the space or resources to accept the large numbers of refugees that are seeking asylum. As a result, many refugees spend significant time in refugee camps, which are often not sanitary, sustainable places for healthy living. One intervention to help fix this problem is to modernize refugee camps and turn them into functioning “cities” rather than just temporary gathering places. One group trying to do this is More Than Shelters. The organization’s main goals are to create humane habitations for refugees and displaced people, encourage refugees to shape their own future by providing training and education, and transform refugee camps from short-term shelters to sustainable ecosystems.70

The goal is to design refugee camps and arrival centers for refugees that are based on modern urban design methods. The organization seeks to design camps with the idea in mind that they should be places of dignity, that refugees remember as their first “city.”71 Thus, even if they have to live there a long time, their livelihood while awaiting resettlement is of a higher quality. The organization often uses existing buildings and converts them into shelters for refugees. It applies sustainable business models in order to conserve resources, and test and scale its designs, but does not elaborate on what this means.

Impact

Since its inception, More Than Shelters has worked in camps both inside and outside of Europe, in countries including Jordan, Greece, Nepal, and Germany. These programs have reached over one million participants and developed innovative new technologies used in refugee camps such as solar lamps.72 The effect of these programs is felt most among the refugees themselves, especially women and children, as their places of survival are turned into places of living.73 Refugees who live in cities designed by More Than Shelters can enjoy safety, security, and privacy74—all of which are needed to help them create a new life and be considered adequately resettled.

Gaps

More Than Shelters’ website does not have any impact information. The organization does not clarify what it means by “reaching” one million participants. The organization is also unclear about how many camps it has renovated. This lack of clarity may be due to the fact that the long-term effects of city planning and development can only be measured many years in the future. It is too soon to really know if More Than Shelters’ intervention will really have positive consequences for its beneficiaries in the long term. The lives of refugees are constantly changing, and since something like urban design takes careful planning, jumping through government loopholes, fundraising, and much more, refugees often need more immediate solutions than More Than Shelters can provide. More Than Shelters faces legislative, economic, and social obstacles as it strives to establish tangible consistency for refugees whose lives are constantly changing.75

Preferred Citation: Jenna Vasquez. “Inadequate Resettlement of Refugees in the Southern European Union.” Ballard Brief. August 2021. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints