Intimate Partner Violence against Women in Uganda

By Mary Claire Eyre

Published Fall 2021

Special thanks to Jamie LeSueur for editing and research contributions

Summary+

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a major issue in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in the country of Uganda. Three major types of IPV have been identified in Uganda: intimate partner physical violence, intimate partner emotional violence, and intimate partner sexual violence. Sixty-five percent of women in Uganda report experiencing at least one of these types of IPV.1 The major contributing factors to IPV in Uganda include cultural attitudes about violence among both women and men and patriarchal behaviors among men. Bride price, or the exchange of goods for a bride, and male alcohol abuse also raise rates of IPV among women. Victims of IPV suffer a variety of consequences, including physical consequences such as bruising, burns, and broken limbs, and mental health consequences such as depression and PTSD. Increased rates of HIV is perhaps the most dangerous consequence of IPV among women in Uganda. Current IPV interventions are focused on community mobilization and education of both men and women on the dangers of IPV in their relationships and households.

Key Takeaways+

Key Terms+

Bride price—The exchange of goods, including livestock and money, for a bride. The price is paid by the groom’s family to the bride’s family. If the marriage ends, the bride-price must be paid back by the bride’s family.2

Intimate partner violence—Physical, emotional, or sexual violence performed by a current or former partner or spouse.3

Sexual dysfunction—Any problem that causes a lack of desire to participate in sexual behavior. Sexual dysfunction is often caused by issues such as sexual trauma, psychological issues, and alcohol use.4

Battered women syndrome—Refers to the state of women with physical and psychological injuries, whether obvious or not, caused by abuse from partners or spouses.5

Physical violence—Abuse such as hitting, kicking, or burning.6

Sexual violence—Forcing or attempting to force a partner into participating in a sexual act.7

Emotional violence—The use of verbal and nonverbal communication in order to cause harm mentally or emotionally. Examples include blackmailing, threats of other kinds of violence, and humiliation, and others.8

Economic violence—Any activity that causes economic harm to an individual. This can include restricting access to financial materials, destroying property, or restricting access to education.

Context

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as “physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, or psychological harm [perpetrated] by a current or former partner or spouse,” as well as any discriminatory behavior against a partner.9 According to the WHO, discriminatory behavior is defined by a certain list of behaviors, including “isolating a person from family and friends, monitoring their movements, and restricting access to financial resources, employment, education or medical care.”10 Physical violence and emotional violence are highly correlated with each other.11 It is likely that if one is present, the other will be as well.12 Sexual violence is only marginally associated with physical violence and is not associated with emotional violence.13 According to the latest IPV study completed by the World Health Organization, IPV tends to be most common in Africa and in the Pacific Islands.14 Uganda, a country in East Africa, had the tenth highest lifetime prevalence of IPV in the world as of 2018. Forty-five percent of women in Uganda experienced physical violence and sexual violence.15 In comparison, the pacific island of Kirabiti had the highest prevalence of IPV in 2018, with physical and sexual violence rates at 53%.16 On the other side, the eastern European countries of Armenia and Georgia had the world‘s lowest lifetime prevalence of IPV in 2018, with rates at 10%.17

In the context of this brief, a partner is defined as someone who is married to another person or lives with them in a romantic relationship.18 These relationships can be current or noncurrent.19 In intimate partner relationships, it is more common for women in Uganda to experience IPV than it is for men.20 Although very few studies have been done on the prevalence of IPV against men, in 2000 it was reported that 19.8% of men experienced some form of IPV, as opposed to 65% of women.21 About 18.7% of men experienced verbal abuse, which includes shouting and yelling, as opposed to about 40.1% of women.22 Only about 3% of men experienced physical violence, whereas about 39.2% of women experienced physical violence.23 According to these statistics, men experience less than a tenth of the physical violence that women experience.24 While it is important to note that these statistics may be falsely reported due to self-selection bias, they indicate that IPV against women is a more prevalent issue.25 In addition, there is no data on IPV perpetrated by Ugandan women against women or by Ugandan men against men in homosexual relationships, largely due to the small size of the openly gay community in Uganda.26 While this does not mean that IPV against men and IPV in homosexual relationships should not be addressed, this brief will focus on IPV enacted by men against women.

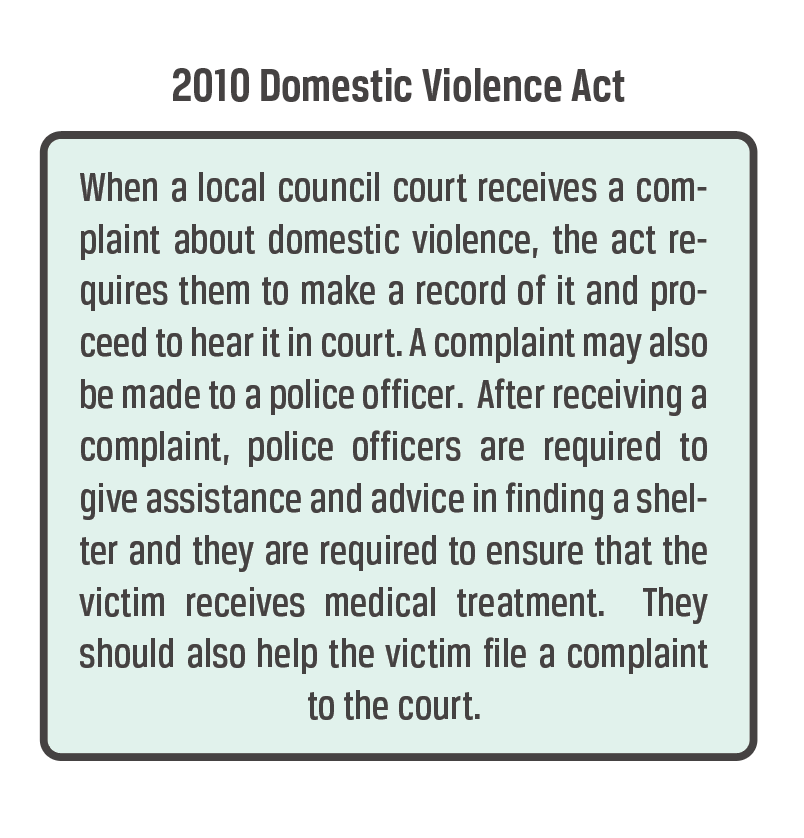

The first laws against IPV first emerged over twenty years after the creation of Uganda’s constitution in 1988.27 Under the 2010 Domestic Violence Act, IPV is now illegal in Uganda.28 This act specifically criminalizes domestic violence as defined as physical, sexual, and emotional violence, as well as economic abuse.29 Perpetrators must pay a maximum fee of the equivalent of $384 or receive up to two years in prison,30 with the exact fees or prison sentences chosen by judges on a case-by-case basis. Yet statistics show that since the 2010 Domestic Violence Act, IPV has become a bigger problem in Uganda. The Universal Peace Federation (UPF) recorded 163 deaths of women in Uganda due to domestic violence in 2016, almost a 50 percent increase from 2010 when the act was passed.31

Contributing Factors

Gender Roles, Patriarchy, and Inequality within the Home

Societal customs and gender expectations in Uganda have led to a culture of patriarchy, which enables IPV against women. Gender norms and roles within Ugandan homes are very traditional, with women handling the household responsibilities and men providing financial support. A study completed in 2015 showed that according to 89.6% of study participants in Uganda, a woman’s most important role is to take care of her home and to cook for her family.32 Although women are the primary homemakers in Uganda, they are less involved than their husbands in making household and family decisions regarding finances, education, and employment. According to a 2016 study that surveyed 960 Ugandan men and women, 73.7% of participants believed the men should have the final word on decisions made in the home.33 For example, only 44% of polled women in Uganda had a say on how their earnings were spent. 34 This belief contributes to IPV because women who reported their husbands as limiting their decision-making power had quadruple the risk of experiencing physical violence.35 Thus, those that do not make decisions with their husbands were more likely to experience violence. Similarly, controlling tendencies between partners are associated with women fearing their male partners.36 These controlling tendencies include physical violence as well as behaviors such as husbands insisting on knowing where their wives are at all times and not allowing them to contact their families.37 When women are afraid of their partners, they are far less likely to be willing to report or discuss the domestic violence they are experiencing to either their partner or a third party.

Not only does Uganda’s history of patriarchy make it likely that women will experience IPV in their relationships, this history also makes it difficult for women to leave violent relationships. In a 2016 study, 67.4% of young male and female Ugandans believed that women need to tolerate violence in order to keep their families together, and these beliefs are at a higher percentage among women than among men.38 Thus, women are even less likely to make efforts to leave abusive relationships. It is also difficult for women to get out of domestic violence situations via divorce. In Uganda, a woman requires more grounds for requesting a divorce than a man does.39 A UN analysis of Ugandan law stated, “While both men and women can apply for divorce, a woman may apply for divorce only if she can prove that the husband is adulterous and abandons her for more than two years or commits other specified acts. Men, however, need only to accuse the woman of adultery in order to file for divorce.”40 Although evidence showing a gender-based discrepancy in divorce rates is unavailable since there are no public statistics on the number of divorces achieved by men and those achieved by women, it can logically be inferred that women in Uganda have less power to divorce than men, and therefore they have less power to get out of bad home situations and escape IPV via divorce.

When young people observe gender inequity in their homes, it is likely that both boys and girls will perpetuate the unequal behaviors in their future relationships and the associated risk for IPV. In a 2016 study, 91.5% of Ugandan girls ages 10 and 14 agreed with the statement that men should have the final word on decisions in the home.41 This high statistic implies that Ugandan women in the rising generation will continue to accept a submissive role in decision-making processes and thus perpetuate the risk of IPV in their future households. Boys are also likely to follow the behaviors they see in their homes. In one study, it was found that when a boy’s father beat his wife, that boy was 11.8% to 13% more likely to perpetrate IPV against his own wife later on.42

Barriers to IPV Law Enforcement

In 2010, the Domestic Violence (DV) Act put laws in place to discourage IPV,43 providing two avenues in which people can report domestic violence—through local council courts and through police officers.44 Despite these laws and processes, the DV Act is not enforced and reports are rarely made. This perpetuates IPV. As of 2014, the date of the most recent report, no one had been prosecuted or convicted under the DV Act.45 There are three main reasons that this is the case: lack of knowledge about the act among law enforcement and legal professionals; a lack of funding for programs; and government corruption.

The first reason that the DV Act is not enforced is a lack of knowledge among officials. Ugandan police and law enforcement officers often do not have the knowledge to enforce the DV Act.46 According to one study, many legal professionals and law enforcement officers do not know about the DV Act. Some judges and magistrates do not even have copies of the act.47

Source: Ugandan Parliament. 2010. “Domestic Violence Act 2010.” (March): 1-20. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---ilo_aids/documents/legaldocument/wcms_172625.pdf

Source: Office on Violence Against Women. 2017. FY 2017 Budget Request At A Glance. https://www.justice.gov/jmd/file/822296/download

The second is a lack of funding for programs. The lack of funding for IPV programs makes it challenging to enforce domestic violence laws. In 2016 and 2017, the equivalent of $450,000 was allocated to Violence Against Women (VAW) programs in Uganda. For comparison, the US spent 480 million dollars on VAW programs in 2016.48 This spending allocated $13 per person in the US for domestic violence issues, whereas Uganda allocates about 1 cent per person for domestic violence issues. This lack of funding means that there is a lack of domestic violence workers. In 2016 and 2017, the cabinet of the government covering gender, labor, and social development problems had only 10 members, and the family protection unit of the police in Uganda had less than 6 police officers assigned to each district of the country.49 There is also a lack of shelters to which the police officers can send abused women.50 As of August 2020, there were 16 government shelters across the country.51 Uganda has a square land mileage of 76,100 miles;52 76,100 miles divided by the 16 shelters is approximately one shelter per 4,756 square miles. Thus, some people would have to travel thousands of miles to reach a shelter.53, 54

The last reason that the DV is not enforced successfully is corruption among police officers and among government workers. In fact, some police officers and government workers actively encourage IPV. One member of parliament illustrated this in a statement he made in 2018. He said, “As a man, you need to discipline your wife. You need to touch her a bit, tackle her, and beat her somehow, to streamline her. If you leave her unpunished, she may become an undisciplined wife and this practice of not beating women has actually made them stubborn.”55 In addition, it is common for law enforcement officers to perpetrate violence themselves. In a study completed in 2020, it was found that about 31.7% of reported violence cases were perpetrated by law enforcement officers.56

Bride Price

Bride price increases IPV in Uganda because it encourages women to be treated like purchases. Bride price is defined as the exchange of goods, including livestock and money, for a bride.57 The price is paid by the groom’s family to the bride’s family.58 Traditionally, if the marriage ends, the bride price must be paid back by the bride’s family,59 making it difficult for wives in abusive marriages to leave and go back to their childhood homes if their family cannot pay back the bride price. 60 In 2015, this refunding aspect of bride price was made illegal. In other words, it is now illegal for a groom’s family to demand a repayment after a divorce occurs. However, this law is rarely enforced.61 Bride price is common in Uganda, especially in rural communities, but it also occurs in urban centers.62 Unfortunately, there is no specific data on the percentage of marriages that involve bride price, but the practice remains common throughout the country.63

Bride price results in the commoditization of women.64 This means that if a woman does not fulfill her traditional role as a childbearing, household-keeping woman or attempts to leave her situation, she is no longer worth the bride price.65 Men often see this as justification for beating their wives.66 Rhetoric reflecting this belief and practice can be seen in many case studies throughout the country of Uganda. For example, Mifumi, a Ugandan organization dedicated to eliminating IPV, has reported cases where men refer to women as cows when abusing them.67 Bride price is practiced all across the country.68 As a result, in a 1996 study, 95% of women believed that bride price was needed in order to make a marriage valid.69 However, in a 2011 study, 65% of the interviewees believed that the impacts of bride price were mainly negative, and 33% thought the impacts were both positive and negative.70 So, although many women believe that bride price is a cultural necessity, this does not translate into a belief that bride price is a positive practice. Only less than 1% of the interviewees believed that the impacts of bride price were always positive.71 The women in the 2011 study who believed that the impacts of bride price were negative mentioned a variety of effects that came as a result of this practice.72 These included being regarded as property, being chastised if they were not seen as valuable enough to make up for their bride price, and subject to beatings if they did not fulfill their traditional duties of having children and running a household.73

Alcohol Abuse

Alcohol abuse among males is tied directly to IPV against women in Uganda. In 2004, Uganda had the highest per-capita alcohol consumption in the world, with a rate of 19.4 liters. This rate has declined by 2020, but Uganda still has the 5th highest rate of alcohol consumption in Africa at 9.5 liters per capita.74, 75 For comparison, the bordering country of Kenya has an alcohol consumption rate of 3.4 liters per capita.76 Approximately 40% to 50% of women from two different studies reported that their partners got drunk “often,” “occasionally,” or “sometimes.”77 One third of women reported that their husbands got drunk everyday or almost every day.78 The frequency of drunkenness makes a big impact on the frequency of IPV. According to one study, women whose partners got drunk often were 6 times more likely to report physical violence than those whose husbands never got drunk, and those whose partners got drunk occasionally were 2.5 times more likely to report physical violence.79 In addition, women whose husbands drank before sex were five times more likely to face IPV than those whose husbands did not drink before sex.80 It is important to note that while drinking alcohol on the men’s part does increase the likelihood of IPV, it is not an automatic predictor of abuse against women.

Negative Consequences

In this section, multiple statistics from other countries are referenced due to a lack of studies on physical health and mental health issues in Uganda specifically. Because of this, not all information will be exactly applicable to Uganda, but the data presented was chosen because it is a good representation of health statistics in Africa in general.

Physical Health Consequences

Physical health problems are a prevalent consequence of IPV in Uganda. About 36% of women in Uganda experience some degree of intimate partner physical violence.81 Physical violence results in a variety of physical injuries. Bruising is the most common consequence of this type of violence. 82 In one particular study, about 23,000 women in Nigeria were surveyed, and 26% of the women who reported a lifetime prevalence of IPV experienced bruising. Other common effects of physical violence in this study were injuries to the eyes and ears, sprains, dislocations, and minor burns. Less common reported effects included severe burns, wounds, broken bones, broken teeth and other serious conditions, which 6% of women experienced. 83 While stabbing, severe burns, and other intense acts of violence are not as common as bruising and smaller injuries, these issues still affect a significant proportion of women in Uganda. Women who are pregnant are particularly susceptible to injury. Pregnant women who experience IPV are far more likely to experience pregnancy complications due to physical violence than pregnant women who do not experience IPV. 84 According to a 2005 study completed in Uganda, Ugandan women who experience IPV are about 4 times more likely to be hospitalized during pregnancy than women who do not experience IPV.85 In addition, women who experience IPV are more likely to deal with conditions such as hypertension, premature rupture of membranes, antepartum hemorrhage and anemia.86

Mental Health Consequences

IPV has implications not only for the body but also for the mind. In a study completed in Egypt, 88% of women who experienced any form of intimate partner physical violence also experienced anxiety, and 69% of them experienced depression. Only 63% and 47% of women who did not experience physical violence experienced anxiety and depression, respectively. 87

Studies show that marital rape victims are at equal risk for a multitude of mental health disorders as victims of stranger rape.88 These disorders include major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, and sexual dysfunction.89 Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is another very prevalent negative mental health consequence of IPV. It is estimated that women in Uganda who experience IPV are 3 times more likely to experience PTSD than those who do not experience IPV.90 PTSD manifests itself in multiple ways among abused women. For example, they may have trouble falling and staying asleep, have nightmares and flashbacks, or become emotionally numb.91 Depression is another common negative mental health consequence of IPV.92 Women in Uganda who experience IPV are 2.04 times more likely to experience severe sadness than those who do not experience IPV.93 IPV is also linked to postpartum maternal depression.94 One study performed in Tanzania, a country that neighbors Uganda, found that women who experienced IPV during pregnancy were over 3 times more likely to experience postpartum depression than those who did not experience IPV.95

Mental health disorders like these sometimes result in suicide for women in Uganda.96 Ugandan women who experience IPV are 3.3 times more likely to experience suicidal ideation than those who do not experience IPV.97

Risk of HIV/AIDS

Experiencing IPV increases the risk of contracting Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS). HIV is a virus that leads to AIDS, an immune system disease where the body is not able to effectively fight off infection.98 HIV/AIDS is the leading cause of death among females of reproductive age worldwide, and 80% of women living with HIV/AIDS are in sub-Saharan Africa.99 If a woman experiences intimate partner violence, she is more likely to experience HIV.100 The most direct pathway from IPV to HIV is infection through an act of sexual assault from a woman’s partner.101 Across a few different study populations in Tanzania, sexual IPV was reported amongst 44% of HIV positive women and amongst 23% of HIV negative women.102 This higher statistic shows that sexual violence is more common in women that have HIV and less common in women that do not have HIV. This tendency is likely because men who are more likely to participate in sexual violence against their wives are also more likely to participate in behaviors that would lead them to acquire an HIV infection, such as concurrent sexual relationships, transactional sex, and substance abuse where unclean needles are used to share drugs.103 In addition, the ways that women have been encouraged to go about HIV prevention often lead to more IPV, increasing their HIV risk. 104 For example, refusing to have sex with their husbands often leads to more violence for Ugandan women.105 To avoid violence, women often choose to put themselves in situations where they could potentially contract HIV from their husbands or partners during sex.106

Sexual violence is not the only path to HIV, however. Physical violence is also associated with increased risk of HIV and other STD infections.107 Genital injuries where blood is exchanged such as vaginal and anal lacerations are more likely to occur during forced, violent sex. These lacerations increase a woman’s likelihood of contracting HIV due to the virus’s direct access to the bloodstream.108

Source: PathLabs, Team Dr Lal. “What Are the Important Effects of HIV on The Body?” Dr Lal PathLabs Blog. Last modified December 10, 2019. Accessed July 14, 2021. https://www.lalpathlabs.com/blog/the-effects-of-hiv-on-the-body/.

About HIV/AIDS.” 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 3. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/whatishiv.html

Because HIV is transmitted through bodily fluids, including semen, sexual violence increases the liklihood of HIV contraction.109, 110 HIV ultimately leads to AIDS after the virus builds up in a victim’s system and begins to destroy immune cells.111 Without proper medication, AIDS can lead to death for many abused women within 3 years of contraction.112 A study done in Rakai, a small city in southern Uganda, found that 73% of all deaths occurred due to complications with HIV and AIDS.113 Since HIV/AIDS compromises the immune system and leads to other infections and diseases, the deaths associated with these secondary conditions are often attributed to HIV/AIDS.114 For women in Uganda, HIV is almost always fatal.115

Practices

The SASA! Program

The SASA! program was created by the organization Raising Voices and is implemented by the Center for Domestic Violence Prevention (CEDOVIP), both of which are based in Kampala, Uganda.116 It is unclear from the website exactly when this program began, but the earliest studies done on it were completed in 2007.117 The program continues to be utilized in Uganda as of 2021.118 Raising Voices uses grants to fund the scaling of the SASA! program, including grants from the UN trust fund, which were given from 2010 to 2012 and from 2015 to 2018.119

SASA! is a series of classes given in communities taught by community activists.120 Community activists are influential members of each community that SASA! employees identified, selected, and trained.121 They are selected in a number of ways: through recommendations from local leaders; recommendations from other violence prevention organizations in the community; and through posting flyers throughout the community.122 The activists are taught about the dangers of intimate partner violence, how to market the program and find students, and how to facilitate activities.123 After being trained, these activists go around the community, asking friends, family, and neighbors if they would be interested in participating in the SASA! program.124

Activists are provided with materials from which they can choose teaching activities that will best fit the needs of their community.125 For example, an activity might be a large group game like life-size chutes and ladders, where violence results in going down chutes and acts of kindness result in climbing ladders.126 Informational classes on different aspects of IPV are also taught for different groups.127 For example, a class that may be utilized during the SASA! program is one that teaches men about the importance of using condoms to avoid HIV.128 Some of these classes are not taught in formal settings but are instead taught in the workplaces of the learners who cannot put down their work to join SASA! activities and classes.129

Impact

There are two ways in which activists evaluate impact after SASA! programs are finished. These include qualitative assessments where activists talk with participants about their experiences and record their answers, and surveys, where quantitative data on outcomes is gathered.130 A study compiling surveys and qualitative assessments taken between 2007 and 2012 shows the impact of the SASA! program on Ugandan community members between ages 18 and 49. According to this study, SASA! achieved many of its desired outcomes. The intervention was significantly associated with lower social acceptance of IPV among both women and men. The percentage of women that believed IPV was acceptable dropped from 57% to 32%, and the percentage of men dropped from 27% to 18%. In addition, there was evidence of a more widespread belief among both men and women that women can refuse sex. The percentage of men that believed women could refuse sex jumped from 53% to 97%, and among women, it jumped from 41% to 90%. Physical violence experienced among women dropped from 25% to 9%. Lastly, reported sexual concurrency among men in the past year was significantly lower than in control communities. It started out at 40% and dropped to 27%.131 Other indicators similarly improved. Condom use increased from 29% to 33%, whereas use decreased in the control group.132 In addition, the percentage of women reporting that their male partner participated in housework increased from 56% to 72%.133

Ultimately, 76% of men and women exposed to the SASA! materials believed that violence against a partner was never acceptable, compared to 26% in control communities.134 The data that SASA! collects is used to evaluate what the successes and challenges of each program were.135 This data can then be used to find out what changes should be made to plan and improve follow-up activities.136

Gaps

Exposure to the program was higher among men than among women. In this study, a random sample of 18- to 49-year-old community members in Kampala, Uganda (where the SASA! program was completed) were surveyed. About 91% of the surveyed men had been exposed to SASA! materials, and about 68% of the women had been exposed. In addition, about 85% of the men had been exposed to all three types of interventions that SASA! uses (materials, activities, and multimedia events), and about 53% of the women had been exposed to all interventions.137 As a result of this exposure, key indicators in the study changed much more for the men than for the women. Out of the 13 survey questions given to women, only 2 of them showed significant improvement: women felt more able to refuse sex with a partner and they made more decisions jointly with their partner.138 Out of the 11 survey questions given to men, however, all 11 of them showed significant improvement.139

In addition, not all of the desired outcomes were achieved. Physical IPV went down from 25% to 9%, but the prevalence of sexual IPV went up from 13% to 14%. This change from 13% to 14% was not statistically significant, so there was no significant change in sexual IPV due to the SASA! program. The researchers did not get information at the beginning of the survey on the community response to women who had experienced IPV in the past year. Thus, there is no available information on the improvement of community response in intervention groups over time.140

Preferred Citation: Mary Claire Eyre. “Intimate Partner Violence against Women in Uganda.” Ballard Brief. October 2021. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints