Lack of Quality Civic Education in Public Schools in the United States

By Sydney Ward

Published Spring 2022

Special thanks to Robyn Mortensen for editing and research contributions

Summary+

A lack of quality civic education affects nearly every K-12 student in the United States. The content and methods of civic education curriculum focus on memorization, lecture, and textbook learning, creating an ineffective learning method for students. Teachers are met with polarized classrooms and communities, creating hesitancy to approach political topics while inequity in funding between states and districts leaves schools without consistent resources or emphasis on civics. Legislative policies and nonprofit organizations have dictated some of civic education’s most recent standards and practices, though this federal approach has not been universally adopted in local classrooms. As a result of this lack of quality civic education, marginalized students are not given the same teacher or curriculum resources their more wealthy or white peers are, which contributes to the gap in the development of civic skills. Political polarization increases among youth and pervades into adulthood. Further, knowledge gaps develop between students who had access to better civic education opportunities and those who did not. Programs like action civics and other frameworks prioritize participatory learning in K-12 schools and are effective at building civic knowledge and lifelong civic skills.

Key Takeaways+

- The lack of quality education in the United States is characterized by an insufficiency of quality curriculum, deficiency of support for teachers, and a lack of legislative action.

- High-quality civic studies courses, which emphasize critical thinking about current political events, increased the rate that students talk about current events with their peers by 15%.1

- Taking a civic education course has been shown to increase a person’s likelihood to vote by 3% to 6%.2

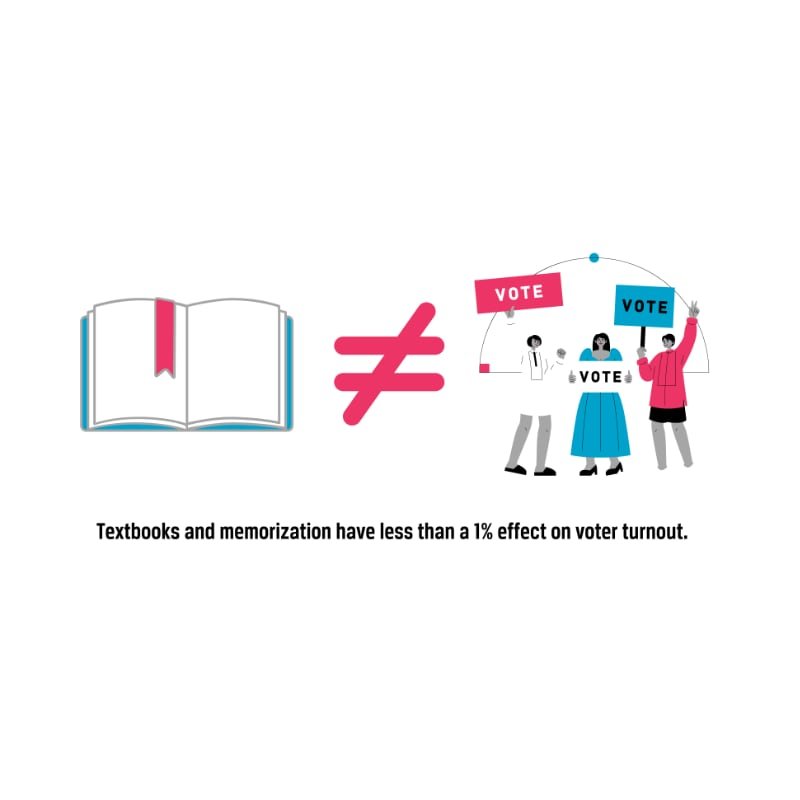

- Textbook-based and memorization-focused civic education has less than a 1% effect on voter turnout.3

- When current issue discussions become contentious, 92% of teachers will “shut down” conversations between students to avoid partisan contention.4

- Federal funding for civics is paid out from the Department of Education through competitive grants, totaling 2.15 million spent in 2021, compared to the 546 million paid out to STEM subjects in 2020.5

Key Terms+

Civics Education Initiative (CEI)—A civics education framework developed by the Joe Foss Institute in 2014 which prioritized the use of a civics test as a requirement for high school graduation.6

Civic self-efficacy—A sense of confidence and competence for a situation, where a person might feel ownership and agency over a task in their community or political arena.7

College, Career, and Civic (C3) Framework—A civic education framework developed by the National Council for Social Studies in 2013. The document focuses on civic education engaged in “(1) developing questions and planning inquiries; (2) applying disciplinary concepts and tools; (3) gathering and evaluating sources to develop claims and use evidence; and (4) communicating conclusions and taking informed action.”8

Critical thinking—Logical, reasonable thinking carried to determine an action or belief. It often incorporates power dynamics to identify who or what might be left out of a situation, and includes ideas of trust and community.9

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)—A 2017 federal law which replaced NCLB. ESSA included provisions that allowed states to determine what curricula best fit their history, demographics, and localities.10 States are required to submit accountability plans to the Department of Education that include descriptions of their goals, standards adoption, and testing plans. Competitive grants incentivize schools to adopt ESSA’s provisions.11

National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP)—A test utilized since the 1960s to measure reading and mathematics nationally, as well as civics and other subjects on a state or local level. The exam is congressionally mandated to report the academic achievement of students, and provides the only state-by-state comparison of learning.12

No Child Left Behind (NCLB)—A 2001 federal law which increased federal oversight and accountability of K-12 school achievement. Special focus was placed on minority and disadvantaged groups of students, and states benefited by receiving funding when implementing provisions of the law. It required all states to report math and reading test scores in the 3rd through 8th grades, among other measures such as yearly progress and teacher qualification.13

The Roadmap for Educating for American Democracy (EAD)—A framework developed by a collaboration of researchers, teachers, and political scientists in 2020 to organize the themes civics education should take. The document outlines seven themes of democratic education and five challenges to overcome with implementation.14

Context

Q: What is civic education, and how are we defining quality civic education in this brief?

A: Civic education is a curriculum centered around developing understanding of US government, constitutional systems, history, and politics. It includes instruction on how to engage with political dialogue, ask critical questions of political systems and histories, and engage with local and national governments.15, 16, 17 Civic education promotes activities such as voting, speaking with legislators, community volunteering and other forms of civic engagement at local and national levels, and it prioritizes skills of deliberation, critical thinking Logical, reasonable thinking carried to determine an action or belief. It often incorporates power dynamics to identify who or what might be left out of a situation, and includes ideas of trust and community., and real world knowledge.18, 19, 20

In this brief, quality civic education is defined as the development of political knowledge and civic skills that leads individuals to participate as an active citizen of the United States.

Q: What is the purpose of civic education?

A: The purpose of civic education is for students to build fundamental knowledge and to develop critical thinking Logical, reasonable thinking carried to determine an action or belief. It often incorporates power dynamics to identify who or what might be left out of a situation, and includes ideas of trust and community. skills about government. Critical thinking is most clearly defined as a practice where students ask questions about and apply content to their own lives or communities.21 Most researchers agree that the development of political knowledge and critical thinking skills are primarily formed throughout civic education in K-12 schooling and strongly indicate civic participation in adulthood.22, 23 High-quality civic studies courses which emphasize critical thinking about current political events increased the rate that students talk about current events with their peers by 15%.24 Taking a civic education course has also been shown to increase a person’s likelihood to vote by 3% to 6%.25 Thus, civic education is a pathway to continued engagement in political processes and a tool to prepare young students to participate as voters and informed citizens in adulthood.26, 27, 28

Q: When and where is civic education taught?

A: Students in 40 states participate in required civic education courses.29 In elementary and middle school, students learn themes of the democratic process in social studies courses, such as learning about local government through field trips and the history of the US in formal history classes.30 These classes might include lessons on American national government, state-specific history courses, or simply general social studies.31 In high school, civics courses might include instruction on the branches of government and their roles, Supreme Court cases, and current events, though exact content varies from state to state.32

Though civic education exists in every school, this brief will focus on civic education in public schools. While charter and private schools also include civic education instruction, curriculum is standardized across public schools to a larger extent and all schools receive some federal funding. Additionally, more research addressing issues of inequality and access to civic education exists for public schools.33

Q: What does civic education look like within the United States?

A: Civic education in the United States typically takes the form of students learning from a textbook, memorizing facts and dates, and taking tests. Teachers typically conduct discussions and engage in lecture learning, and no states have an experiential learning requirement.34 Students may have a lecture-, reading-, or inquiry-based model of instruction, though these vary by grade and school.35 In 32 states, social studies or civic courses include instruction about the Constitution, the different avenues for political participation, the components of democracy, and the setup of governmental systems.36, 37

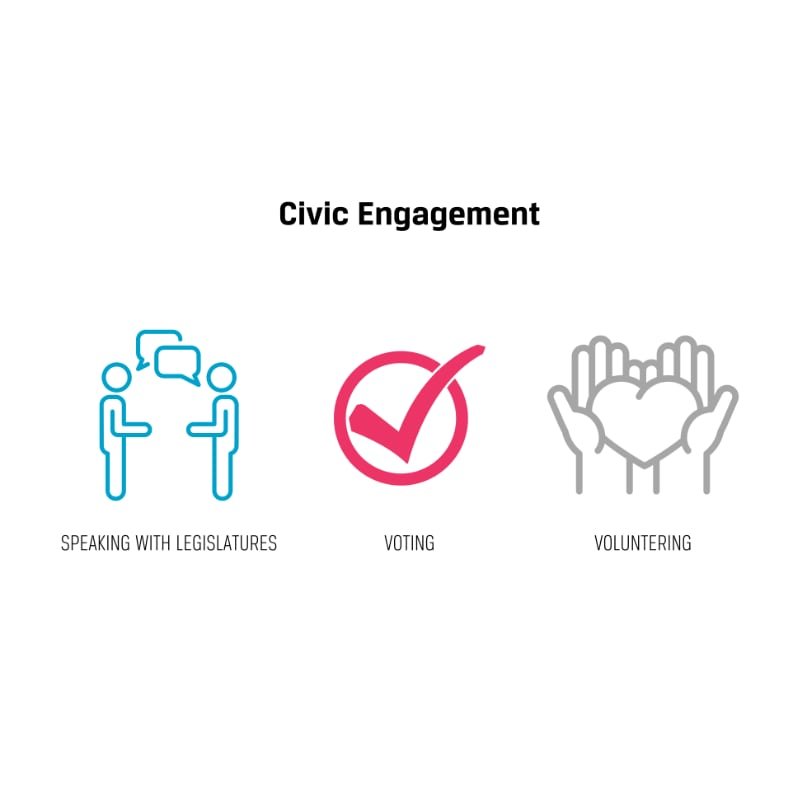

This course design is typical across the US, although states have significant flexibility in implementation of learning measures.38 While each state is different, 17 states require a civics assessment for graduation, 25 states offer service learning opportunities for credit, and 43 require a civics course of some kind.39 These curriculums include instruction on forms of government, political history, and the branches of the US government, though there are variations between states.40, 41 Of those 40 states with a civics requirement, only 9 of those states and the District of Columbia require a one-year civics course for graduation.42

While the United States has specific classes dedicated to civic education curriculums, countries such as Germany and Belgium integrate civic education into all other subjects in school, such as math or science curriculum that includes instruction on civic duties within that field.43 These classes might include an emphasis on climate change globally, or develop competencies in researching a diversity of scientific sources.44 This structure contrasts to the isolated political education US students receive.45, 46 Other countries, such as the UK and Germany, tend to center global citizen education and human rights knowledge in their civic curriculums, whereas the US does not.48, 49

Q: How has civic education developed in the United States?

A: In the 1830s, civic education was integrated in the public school curriculum. The goal was to teach the basic building blocks of government structures and inspire loyalty to the country as part of the “common school” movement. This initiative preceded the development of public schools, when communities opened their own local schools for children.50, 51 When schools received public funding, curriculum developed locally. Since 2000, there have been two instances of federal legislation that have named civic education within the United States. The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB A 2001 federal law which increased federal oversight and accountability of K-12 school achievement. Special focus was placed on minority and disadvantaged groups of students, and states benefited by receiving funding when implementing provisions of the law. It required all states to report math and reading test scores in the 3rd through 8th grades, among other measures such as yearly progress and teacher qualification. ) of 2001 affected students in grades K-12, emphasizing the importance of STEM subjects and standardized testing, and cutting funding and resources away from civic education.52 With the introduction of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) A 2017 federal law which replaced NCLB. ESSA included provisions that allowed states to determine what curricula best fit their history, demographics, and localities. States are required to submit accountability plans to the Department of Education that include descriptions of their goals, standards adoption, and testing plans. Competitive grants incentivize schools to adopt ESSA's provisions. in 2015, civic education was named in federal grant provisions but never had funding allocated for those programs because of a lack of congressional appropriation.53

Q: How does the United States measure the quality of civic education?

A: There are currently no comprehensive standards for civic education across all 50 states because curriculum is left up to states and is not mandated at the federal level. The main measure of civic learning in the United States is the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) A test utilized since the 1960s to measure reading and mathematics nationally, as well as civics and other subjects on a state or local level. The exam is congressionally mandated to report the academic achievement of students, and provides the only state-by-state comparison of learning.. Unlike other standardized tests in K-12 education, the NAEP is a congressionally mandated measure of student progress, carried out by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).54 From 1998 to the most recent scores in 2018, the NAEP has measured civic knowledge (among other topics) through a test given to a random sample of 8th grade students nationwide.55 While a large part of civic education takes place in high schools, students nationwide are introduced to civic education topics in elementary and middle school, making the NAEP a test that measures learning across the board. The test measures “knowledge, intellectual and participatory skills, and civic dispositions”56 and is one of the only standardized exams taken that does not measure performance on state curriculum standards and instead measures and compares student performance across the nation.57 It features questions about political reasoning, theories of political development, and historical reasoning.58 Additionally, the Advanced Placement (AP) US History and AP US Government exams measure understanding of social studies and civic concepts for the purpose of college readiness rather than measurement of existing K-12 learning. These exams are administered by the College Board, a nonprofit organization which measures college readiness through annual exams in 38 subjects.59, 60 The standardized assessments yield measures that show college readiness and are often correlated with NAEP scores.61

State curriculum as a whole is also measured to gauge effectiveness, often with scales created by independent nonprofit organizations. In a recent analysis 32 states were given a “mediocre” or “inadequate” rating of their civic education curricula based on rigor and comprehensive coverage of topics.62 These states generally provided vague, overly organized standards that failed to focus on critical thinking Logical, reasonable thinking carried to determine an action or belief. It often incorporates power dynamics to identify who or what might be left out of a situation, and includes ideas of trust and community. or comprehension of important political and historical events.63

Q: How are students performing on civic education measures?

A: In 2014, results from the NAEP A test utilized since the 1960s to measure reading and mathematics nationally, as well as civics and other subjects on a state or local level. The exam is congressionally mandated to report the academic achievement of students, and provides the only state-by-state comparison of learning. showed that 24% of students were proficient in civics learning. The 2018 NAEP results showed no significant change from the 2014 test period.64 Civic education measures include AP US Government scores, which have decreased on average over the years. From 2019 to 2021, scores on both the AP US History and AP US Government tests have decreased. In 2019, 24% of students scored a 3 (the standard for proficiency) on the AP US History exam, and in 2021, 21% scored in that category. The AP US Government tests had a similar trend, with 30% scoring a 3 in 2019, and 27% in that same category in 2021.65, 66 Unfortunately, no research exists to definitively highlight how civic education quality impacts these civic education measures. Because of a lack of international research presumably due to funding and logistical constraints, comparison of civic education performance to other countries is unavailable for recent years.67

Contributing Factors

Ineffective Civic Curriculum

Ineffective civic school curriculum decreases the overall quality of civic education within an academic setting due to a lack of emphasis on critical thinking Logical, reasonable thinking carried to determine an action or belief. It often incorporates power dynamics to identify who or what might be left out of a situation, and includes ideas of trust and community. (in the form of questioning and personal application), memorization instead of application, and an unbalanced focus on some topics over others. Content that focuses on facts rather than skill building and methods that prioritize memorization contribute to a lack of quality civic education in the United States. Many states emphasize testing and general concepts, rather than engagement with current events or critical thinking skills. This approach leaves students with knowledge that does not necessarily translate to life-long civic skills.

Content

States consistently do not include real-world knowledge or critical thinking Logical, reasonable thinking carried to determine an action or belief. It often incorporates power dynamics to identify who or what might be left out of a situation, and includes ideas of trust and community. skills in their curriculum.68, 69, 70 These civic skills include research, active listening to peers, and critical thinking that are essential to developing the ability to cast informed ballots, engage with elected officials, and voice opinions in one’s political community.71 One example of this inconsistency is the lack of instruction around political parties and elections. An understanding of political party issues and leanings is necessary to participate in current affairs.72 Though many states cover a wide range of political topics, 43 states require curriculum to include instruction about political parties, but only 10 states mandate the study of controversial political party events, and only 8 require study of political parties’ ideological views.73

Across states, curriculum standards are often vague and simple in nature.74 Overall, most states do not put much emphasis on topics such as due process, federalism, equal protection, and comparative government, while overemphasizing mechanics like the three branches of government.75 Standards also spend more time teaching civics in historical rather than present-day contexts. The combination of these content choices leaves students without an understanding of the nuances of Constitutional and civil rights, which matter in both assessments and in civic life.76 With regard to voter education, while 27 state codes include some language that encourages but does not require high school voter registration education or procedures, these measures aren’t consistent.77 States do not prioritize connection to current events when teaching civics, leaving students with a lack of relevant and relatable instruction.

Methods

Current civic education focuses on memorization, standardized testing, and lecture instruction, providing context for the “what” of civic engagement, but not the “how.”78 Existing memorization strategies (of dates, presidents, and key historical events) and a lack of emphasis on quality writing or research standards do not teach students how to engage with real world civic competencies, such as voting or local political participation.79 Researchers have found that textbook-based and memorization-focused civic education has less than a 1% effect on voter turnout.80 Ninth graders who received textbook and lecture instruction without interactive civic activities scored lower on civic competency tests than those with highly interactive instruction.81 Textbook instruction often consists of books that are too long for school year constraints and include a focus on memorization; as a result, textbooks receive reviews of a lack of engagement from teachers 70% to 90% of the time.82 Textbook learning does not contribute to long-term civic skills, but rather reduces the quality of learning.

As for testing, some teachers in an interview analysis viewed civics tests as something they must teach to encourage the memorization of facts and dates rather than applying content to a contemporary context.83 Methods such as a civics test, required by 17 states to graduate from high school, do not take into account the purpose of civic education: to develop civic skills for political participation. Though a civics test is widely used, it often acts as a passing grade of a students’ ability to act as a citizen—not in exercising real-world political skills but rather in acquiring historical and governmental knowledge.84 Testing reinforces memorization but not skills needed to act as a citizen, which contributes to a lack of quality in the lasting effects of civic education.

In a state by state comparative analysis of standards, states that score lower on curriculum tend to overlook research and deliberation skills.85 Scholars who crafted the C3 A civic education framework developed by the National Council for Social Studies in 2013. The document focuses on civic education engaged in “(1) developing questions and planning inquiries; (2) applying disciplinary concepts and tools; (3) gathering and evaluating sources to develop claims and use evidence; and (4) communicating conclusions and taking informed action.” Standards for Civic Education agree that writing and research skills ensure civics lessons last beyond the classroom.86 These standards are a framework developed by the National Council for Social Studies which focus on questioning and application of concepts learned through communication and action.87 While writing and research standards do exist in some states, they often do not connect to current events meaningfully. Schools which do not prioritize active learning through research or deliberation miss a component of learning that can help internalize civic skills.

Lack of Support for Teachers in Political Education

Inadequate support from schools and the community for teachers in civic education leads to reduced education quality because teachers must decide between standard curriculum and external pressure. When teachers do not feel the support of parents, administration, or the school community, it affects the content and topics they feel comfortable teaching, thus affecting the quality of education received and leaving students without a chance to develop deliberative skills such as critical thinking Logical, reasonable thinking carried to determine an action or belief. It often incorporates power dynamics to identify who or what might be left out of a situation, and includes ideas of trust and community. and careful analysis. Teachers are not typically given training on how to address political or controversial events in the classroom. In qualitative analyses, researchers found a lack of consensus among teachers on the role they play as civic educators and the role of the school in the process of political socialization.88

Furthermore, most schools currently do not offer training for teachers to navigate polarization, research on classroom management in such situations is lacking and many find a lack of administrative support.89, 90 Many teachers lack a background in teaching about polarizing subjects as well as teaching to groups of students who may have vastly different political opinions and expressions. As a result, when current issue discussions become contentious, 92% of teachers will “shut down” conversations between students to avoid partisan contention rather than facilitating a constructive discussion.91 With more substantial training, teachers may be able to facilitate constructive conversations about current events and politics without risking contention.92, 93 These examples highlight inadequate support for teachers, and thus show how a lack of resources and training can facilitate less quality education, avoiding current events and application altogether.

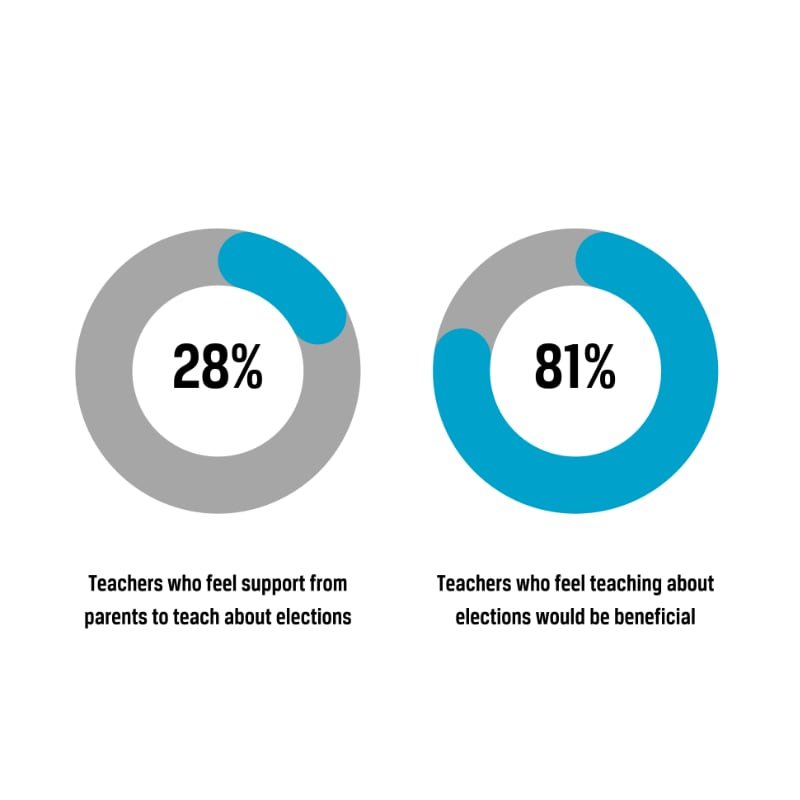

Parental involvement, or a lack thereof, can also have a large influence on teachers’ willingness to discuss politics in the classroom. Schools tend to be non-neutral political grounds, due to community influences and the rules and logistics that govern them.94 As a result of parental influence, only 28% of teachers think parents would be supportive if they taught about an election, even though 81% of teachers report that teaching about an election would help them meet state curriculum standards, according to a report by the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement.95 On the other hand, in communities where teachers perceived consensus between parental and personal political beliefs, teachers were more confident in their decisions to teach what they did in terms of election coverage. In schools located in more polarized districts, teachers were much more cautious about making clear references to current events.96 This reality means there is a disconnect between what teachers feel the need to teach and what they feel prepared and supported to teach in terms of civic education and current events.97 While 98% of civic educators have reported a desire to teach the importance of civic education, that desire is often impeded by political polarization and fear of backlash from the community, as shown by a 2013 nationwide survey of teachers.98 Without support from parents, administration and the community, teachers may avoid controversy and current events altogether.

In most cases, teachers are the primary influence on student learning and conceptualizations of citizenship and history in the United States, though an unwillingness to adopt national-level teaching standards and civic curriculum may create discrepancies in how teachers implement standards across districts.99

Legislative and Organizational Influence on Civic Curriculum

A majority of the US’ civic education curriculum has been facilitated by national legislation and curriculum initiatives, often leaving teachers without the resources to implement them. Common Core standards for education developed in partnership between state curriculum experts to develop a consistent set of education standards in 2010. These standards placed an emphasis on “college and career readiness,” offering no mention of “civics” in the standards for states.100 Common Core was adopted by 47 states, and has encouraged classroom instruction to function with memorization and testing methods.101, 102 Adoption of the Common Core standards guaranteed states and schools with federal funding, which was not otherwise accessible. As a result, civics was added onto Common Core standards by teachers who made an effort to include it, not as a default. This action spurred a lack of quality civic education, because teachers became more focused on implementing standards to secure funding rather than emphasizing real-world learning experiences.103

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) A 2017 federal law which replaced NCLB. ESSA included provisions that allowed states to determine what curricula best fit their history, demographics, and localities. States are required to submit accountability plans to the Department of Education that include descriptions of their goals, standards adoption, and testing plans. Competitive grants incentivize schools to adopt ESSA’s provisions. of 2015 replaced Common Core and shifted the focus of education to standards that prioritized a wider range of subjects but did not abandon the legacy of NCLB A 2001 federal law which increased federal oversight and accountability of K-12 school achievement. Special focus was placed on minority and disadvantaged groups of students, and states benefited by receiving funding when implementing provisions of the law. It required all states to report math and reading test scores in the 3rd through 8th grades, among other measures such as yearly progress and teacher qualification. ’s STEM emphasis. Funding was expanded to include competitive grants to states and districts with need for civic education funding and provide professional development opportunities to teachers.104 ESSA opened the door to civic education advocates assisting in developing curriculum and measuring civic education as a marker of a “well rounded education.” Each year schools send in a curriculum plan to the Department of Education that, when approved, receives funding. In total, 14 states have added reference to civic education in their federally-reported ESSA plans, with 8 adopting the C3 A civic education framework developed by the National Council for Social Studies in 2013. The document focuses on civic education engaged in “(1) developing questions and planning inquiries; (2) applying disciplinary concepts and tools; (3) gathering and evaluating sources to develop claims and use evidence; and (4) communicating conclusions and taking informed action.” framework. However, ESSA A 2017 federal law which replaced NCLB. ESSA included provisions that allowed states to determine what curricula best fit their history, demographics, and localities. States are required to submit accountability plans to the Department of Education that include descriptions of their goals, standards adoption, and testing plans. Competitive grants incentivize schools to adopt ESSA’s provisions. has funded 1% or less of its intended titles and does not require civic education to be funded.105

Each state has its own civic education standards and largely retains autonomy over them. However, teachers often do not react favorably when presented from top-down legislation determining curriculum.106 In Utah, one school implemented new civic education changes along the lines of the C3 A civic education framework developed by the National Council for Social Studies in 2013. The document focuses on civic education engaged in “(1) developing questions and planning inquiries; (2) applying disciplinary concepts and tools; (3) gathering and evaluating sources to develop claims and use evidence; and (4) communicating conclusions and taking informed action.” framework that were largely ignored by teachers because of these reasons.107 Such standards, like state based legislation and local implementations of NCLB A 2001 federal law which increased federal oversight and accountability of K-12 school achievement. Special focus was placed on minority and disadvantaged groups of students, and states benefited by receiving funding when implementing provisions of the law. It required all states to report math and reading test scores in the 3rd through 8th grades, among other measures such as yearly progress and teacher qualification. , ESSA, or Common Core, are varied within districts as they have differing willingness to implement changes.108 State-guided civic education initiatives inspired by national legislation were viewed by teachers largely with dismissal, and districts often failed to implement them consistently.109

Educational Funding Inequity

Funding at the federal and state levels for education prioritizes STEM courses and assessment-driven curriculum. As a result, the quality of civic education is directly impacted by resource cuts. Federal funding for civics is paid out from the Department of Education through competitive grants, totaling $2.15 million spent in 2021, compared to the $546 million paid out to STEM subjects in 2020.110 Competitive grants are awarded based on an application and the discretion of a team of reviewers.111 Separately, the federal government subsidizes 10.2% of state education budgets, while localities and states provide the rest.112 The federal government spends $0.05 per pupil on civic education funding, compared to $0.50 per pupil on STEM subjects.113 This discrepancy has a large impact on the learning resources available and time spent on instruction for civics.114 Federal measures to boost education nationwide have neglected money for civic education. Title VI of ESSA A 2017 federal law which replaced NCLB. ESSA included provisions that allowed states to determine what curricula best fit their history, demographics, and localities. States are required to submit accountability plans to the Department of Education that include descriptions of their goals, standards adoption, and testing plans. Competitive grants incentivize schools to adopt ESSA’s provisions. allocated grant money in part to civic education but thus far has struggled to be fully funded, if at all. While Title I and other provisions have been prioritized in the federal education budget, civic education largely falls under the Title VI “Student Support and Academic Enrichment” provision, which is not prioritized as highly as other subjects.115 States must prove expenditures up to a certain point to receive federal funds, with percentage requirements within that federal grant.116 In 2019, the federal government spent $5 million on civic education but $3.2 billion on STEM education nationwide.117

School funding across zip codes varies widely, as does this federal support, making it so civic education is not consistently financed. In the US today, 45% of schools’ budgets come from local property taxes. This is evidence that wealthy school districts receive more funding for their schools, while poorer districts get less.118 Some states have diversified funding sources for education to include more than just property taxes. New Mexico, for example, routes 70% of education funding through the general state fund, mineral revenues, and other statewide sources.119 The vast majority of states still see large disparities between districts.120 Individual states, however, like Massachusetts, have passed bills to specifically allocate money to civics equally across districts and codify its importance.121 The state scored among the top five in the country on civics standards as a result of boosting resources through funding and emphasis.122 Two case studies of educational inequity between states can be used here. One example is Utah’s latest civic education reform, SB60, which would add a civics test to the curriculum. Districts with the least per pupil funding were left without staff to administer the changes and had teachers responsible for integrating that legislative push into curriculum, without adequate support. This led to less of an emphasis on the exam content and learning, and rather just getting it done which was beneficial to implementation.123 In another example, Connecticut’s charge to adopt new standards was also met with mixed reception across districts with fewer resources. Those without curriculum coordinators saw much lower adoption than those with dedicated staff.124 Neither provided significant financial support for such programs. These resource cuts directly negatively impact the quality of civic education possible within school districts. Further, inconsistent and varied funding measures from states and the federal government affect the resources, consistency, and quality of civic education nationwide.

Consequences

Development of Knowledge Gaps

A lack of quality civic education means that there are inconsistencies in how much students know about political life across the country. Overall, students who go through the civic education curriculum graduate with little to no memory of important historical and political events. For instance, 60% of college students failed to know a requirement for amendment ratification and 40% knew that Congress had the power to declare war,125 and only one-third of adults could name all three branches of government in a recent study.126

A lack of quality education that shows a robust view of the country’s political beliefs also contributes to the development of regional political ideologies. One study found that students are likely to have the same political preferences as the majority of their region after going through public school civic education courses.127 When schools do not equalize the civic knowledge field, students do not have an opportunity to develop their civic knowledge or opinions prior to their eligibility to vote. One study found that rural youth from less educated households are likely to be less civically engaged, with the opposite being true for their wealthier peers with more educated parents.128

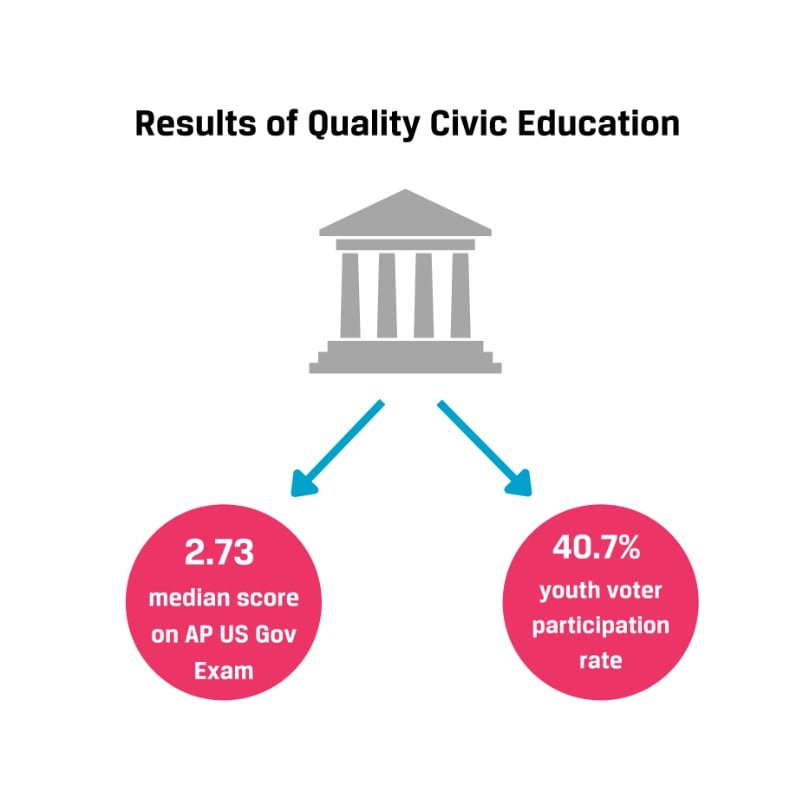

The 15 states with the highest rigor of civic education programs—such as New Hampshire or Arkansas, which require civics classroom instruction for one semester, offer credit for community service, and require a civics exam—had a median score of 2.73 on the AP US Government exam and a median 40.7% youth voter participation rate.129 These scores reflect a consistency in political knowledge development and corresponding action. Students who adopt habits of civic engagement in and after high school are likely to have taken extra civics courses, such as AP US History.130 Even so, only 24% of students are scoring proficiently in the subject based on NAEP A test utilized since the 1960s to measure reading and mathematics nationally, as well as civics and other subjects on a state or local level. The exam is congressionally mandated to report the academic achievement of students, and provides the only state-by-state comparison of learning. test scores.131 A lack of quality civic education that prioritizes active learning, application to real world events, and civic skill development creates disparities in civic knowledge across the nation.

Increase in Political Polarization

Existing civic education that does not address the development of critical thinking Logical, reasonable thinking carried to determine an action or belief. It often incorporates power dynamics to identify who or what might be left out of a situation, and includes ideas of trust and community. about current political events does not prepare students to engage in an ideologically polarized society. From the pre-2000s to 2016, political polarization in the United States rose by 0.48 points since the 1960s, while other countries have only risen by 0.04 points on average. This trend is illustrated by increases in affective political polarization and public distrust in government.132, 133, 134 Civic education is not the only factor in political polarization, but political ideology begins to solidify in adolescence, meaning that the classroom environment in elementary, secondary and higher education is a catalyst for civic development.135, 136, 137

A lack of critical thinking Logical, reasonable thinking carried to determine an action or belief. It often incorporates power dynamics to identify who or what might be left out of a situation, and includes ideas of trust and community. skills through adequate civic education can reinforce partisan beliefs, rather than encouraging meaningful engagement.138 Polarization alienates students in the classroom who may have different opinions or political backgrounds, such as students who may be immigrants or minorities, from discussion.139 As a result, students in the US have experienced a rise in bullying along political and social lines as domestic polarization has increased because of intolerant political opinions.140 Given its current state, civic education is not consistent from school to school and is overshadowed by local or regional political attitudes, resulting in an inadequate system for reducing extreme partisanship.141 Civic education forms a crucial basis of how students learn to engage with their government, and each other, in respectful and understanding ways. Civic education that does not address the development of critical thinking Logical, reasonable thinking carried to determine an action or belief. It often incorporates power dynamics to identify who or what might be left out of a situation, and includes ideas of trust and community. about current political events will not prepare students to engage in an ideologically polarized society. High-quality civic education has been shown to prioritize those skills and engage students across partisan lines to understanding.

Lost Civic Learning Opportunities for Marginalized Students

A lack of quality civic education creates unequal civic learning opportunities for marginalized students because of funding inequity.142, 143 As previously discussed, marginalized students are more likely to attend schools with lower funding than their peers, leading to under-resourced teachers and a stronger reliance on testing.These deficiencies in education decrease the depth of learning through a lack of action-based curricula. As early as 4th grade, students of color in under-resourced school districts perform 3% worse than white counterparts on the National Assessment of Education Progress’ civic indicators test in part due to a lack of opportunity to meaningfully engage with civic education.144, 145 Specifically, students who did not grow up speaking English or whose first language is not English score 37% higher than the average on the NAEP A test utilized since the 1960s to measure reading and mathematics nationally, as well as civics and other subjects on a state or local level. The exam is congressionally mandated to report the academic achievement of students, and provides the only state-by-state comparison of learning..146 This discrepancy is expressed in communities across the country and extends to students who have not lived in the US their entire lives. Varied funding, coupled with economic and racial disparities, creates a school environment where marginalized students are not provided the same civic education opportunities their peers might have.

All students are affected by the “civic empowerment gap,” which describes the ways that civic education impacts future civic engagement and action.147 The racial disparities in this gap are shown in civic and political knowledge most specifically. White adults are over 11% more likely to engage in civic life than those of other races or ethnicities.148 This “civic empowerment gap” means that marginalized students leave K-12 public education less prepared than their peers to participate in the civic process.

Best Practices

Action Civics

Youth participatory programming, often referred to as action civics, has been pioneered by groups such as Generation Citizen. The curriculum centers student agency in the classroom and encourages political action as a component of K-12 civic education. Generation Citizen is an organization that integrates classroom curriculum with real-world projects; their mission is to ensure youth are “equipped and inspired to exercise their civic power.”149 150 They are funded by a number of foundations and organizations, primarily the Hewlett Foundation.151 Action civics typically includes students acting as citizens through researching, planning, implementing, and reflecting on a project for local change in their civic community.152 The program motivates students by allowing the freedom of choice when engaging with their personal community in a project or question.153 By engaging with local communities, diversity, and student agency, action civics programs can develop civic skills that last a lifetime.154 A central piece of action civics includes the development of student voice.155 Student agency and voice in their own civic education is a primer for adult civic decision-making.156 Outcomes of student voice prioritization include “agency, belonging, competence, deliberation and (civic) efficacy.”157 Action civics is particularly powerful when civic skills are applied to communities students live within.158 There are 6 steps outlined by researchers to develop an effective action civics program including: examination of community, issue identification, research and goal setting, power analysis, strategy development, and taking action.159 Essentially, the programming begins with students identifying an issue pertinent to them or their class, then moves to phases of research, action-planning, implementation, and reflection.160

Impact

Experimental trials on Generation Citizen’s programming have been conducted in which teachers opted to adopt the action civics curriculum and then measure their fall and/or spring classes level of civic knowledge, among other metrics, against a control semester of “regular” civic learning. Students who participate in an action civics course through Generation Citizen are 3.8 times more likely to speak up and participate in other classes.161 Though action civics approaches only have a marginal effect on political knowledge, their relevance to the development of long term civic skills outweighs solely classroom instruction-based learning.162 Generation Citizen action civics participants displayed future civic commitment 20% higher than students in typical civic education classrooms. However, specific topics of action civics projects did not necessarily indicate a change in future civic commitment.163 Generation Citizen programs instigated a 26% difference in civic self-efficacy A sense of confidence and competence for a situation, where a person might feel ownership and agency over a task in their community or political arena. between the treatment and control groups.164 Their programs have touched 14,025 students with their programs and launched 561 projects to improve communities nationwide.165 This has yielded outcome data that shows 90% of students involved in the program increased their belief that they could personally make a difference and 91% believed addressing injustice is important.166 From an impact perspective, youth-led, in-classroom curriculum like Generation Citizen’s offer students a valuable setting to learn both the mechanics of government and practice participating.

Gaps

Action civics is impactful, though it does require a significant amount of resources for a teacher both in and outside the classroom. Teachers must have connections to community members, coordinate out of class projects, and manage a roster of student projects that may vary significantly and need one-on-one consulting.167 Additionally, creating a classroom community of nonpartisanship can be difficult, particularly in a polarized political time.168 More frameworks need to be developed to help teachers instruct students in communicating partisan ideas in a civil and productive manner, particularly on social media. Further, ensuring that proper diversity and dialogue between a myriad of stakeholders can be difficult, based on resources and geographic constraints.169 In analysis of action civics programs, comparative data detailing student attitudes was not measured at the beginning of the program, only at the end.

Legislation

Program

The Civics Education Initiative (CEI) A civics education framework developed by the Joe Foss Institute in 2014 which prioritized the use of a civics test as a requirement for high school graduation. has developed a large amount of civic education curricula and resources. CEI now works in tandem with the Arizona State University's Center for Political Thought and Leadership to research civic innovations. In 2014 the organization recommended that a civics exam be administered to high school seniors to assess readiness and civic knowledge to participate as a voting adult.170, 171 The proposal included utilizing the questions on the US Citizenship and Immigration Services Civics Test given to immigrants for naturalization. 18 states passed test-based civics requirements as a result of the framework. States have varied implementations of the CEI framework, some developing their own tests after the pattern of US Citizenship and Immigration Services’, others notating test scores on students’ transcripts.172

Separately, in 2013 the National Council on Social Studies released the College Career and Civic (C3) Framework A civic education framework developed by the National Council for Social Studies in 2013. The document focuses on civic education engaged in “(1) developing questions and planning inquiries; (2) applying disciplinary concepts and tools; (3) gathering and evaluating sources to develop claims and use evidence; and (4) communicating conclusions and taking informed action.”, encouraging teachers to take control over civics curriculum and emphasizing the role of action civics in the learning process. This framework included details on how to develop skills of inquiry and developing claims with research.173 The framework integrated with Common Core standards and allowed for teachers to emphasize civics alongside the Common Core focus of reading and writing. This looked like including free-response writing to historical events and prioritizing primary documents in learning about government.174

In 2020, a third framework was released in partnership with civic organizations and state education offices called the Roadmap to Educating for American Democracy (EAD A framework developed by a collaboration of researchers, teachers, and political scientists in 2020 to organize the themes civics education should take. The document outlines seven themes of democratic education and five challenges to overcome with implementation.). This framework has not been widely implemented in schools to date.175

Impact

While efficacy data is not available on how influential these measures were on a large scale, data is available to describe how many states implemented them. The C3 A civic education framework developed by the National Council for Social Studies in 2013. The document focuses on civic education engaged in “(1) developing questions and planning inquiries; (2) applying disciplinary concepts and tools; (3) gathering and evaluating sources to develop claims and use evidence; and (4) communicating conclusions and taking informed action.” framework was widely popular, with 44 states implementing changes to their state standards pursuant to its objectives, centering inquiry rather than testing.176 Both of these frameworks were adopted across the country, with 21 states implementing both CEI A civics education framework developed by the Joe Foss Institute in 2014 which prioritized the use of a civics test as a requirement for high school graduation. and C3 A civic education framework developed by the National Council for Social Studies in 2013. The document focuses on civic education engaged in “(1) developing questions and planning inquiries; (2) applying disciplinary concepts and tools; (3) gathering and evaluating sources to develop claims and use evidence; and (4) communicating conclusions and taking informed action.” methods, and 21 adopting just the C3 Framework. 8% instituted only CEI testing procedures, while 5 states have not pursued any action in regard to the initiatives.177

Gaps

All of these initiatives were beneficial for learning, but lacked the training and financial support necessary to be uniformly implemented. This further contributes to a lack of quality by affecting the access to equal civic education nationwide.178, 179 Disconnects between advocates and teachers in the classroom on content, in addition to limited classroom and funding sources given to local schools contribute to a lack of widespread adoption. Measuring the extent of implementation and teacher satisfaction with such curriculums could be a next step to understanding the effectiveness of the CEI A civics education framework developed by the Joe Foss Institute in 2014 which prioritized the use of a civics test as a requirement for high school graduation. and C3 A civic education framework developed by the National Council for Social Studies in 2013. The document focuses on civic education engaged in “(1) developing questions and planning inquiries; (2) applying disciplinary concepts and tools; (3) gathering and evaluating sources to develop claims and use evidence; and (4) communicating conclusions and taking informed action.” standards.180

Preferred Citation: Ward, Sydney. “Lack of Quality Civic Education in Public Schools in the United States.” Ballard Brief. May 2022. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints