Mental Health Concerns in Armenia

By Morgan Rushforth and Sara Jensen

Published Winter 2021

Special thanks to Harper Forsgren for editing and research contributions

+ Summary

Armenia is one of many countries whose population faces mental health struggles to a relatively high degree. However, the extent of these struggles is relatively unknown due to the country’s underreporting of recent, accurate data on mental health statistics. Armenia’s mental health crisis can be attributed to many factors, some of which include residual trauma from various events in the country’s history (such as the Armenian Genocide and the earthquake of 1988), domestic violence, perpetuation of cultural stigmas that keep individuals from seeking help for mental illness, and lack of resources and healthcare infrastructure. A few of the most prominent consequences of the crisis include human right violations, lack of economic mobility, and harm to interpersonal relationships. Some of the most common practices used to combat the undertreatment of mental illness include furthered education for both health professionals and the public, and increased advocacy. There are a few organizations in Armenia who are attempting to address these goals with varying success.

+ Key Takeaways

- Armenian mental health care is lacking due to large numbers of individuals requiring those services, and not enough resources being dedicated to mental healthcare

- There are not significant numbers of effective practices consistently being implemented in-country for this issue

- The government has recently been passing legislation that could lead to better mental healthcare in the future, but improvement is mainly speculative at this point and hindered by an ongoing mental health stigma

- A decrease in the stigma against mental healthcare, an increased access to treatment, and deinstitutionalization reforms, mental healthcare would likely improve in Armenia, as well as the general well-being of those with mental health conditions

+ Key Terms

PHQ-9— A module that diagnoses depressive disorders and measures the severity of depression based on the scores from nine diagnostic criteria. The PHQ-9 has thresholds at 5, 10, 15, and 20 which indicate the lower limits of mild, moderate, moderate to severe, and severe depression, respectively.” A score of 15 indicates major depression.1

GAD-7— “A self-report questionnaire with scores of 5, 10, and 15 used as cutoffs for mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, and is used to both screen and measure the severity of generalized anxiety disorder.”2

Mental health disorders— “Disorders that affect your mood, thinking and behavior,” and are also referred to as mental illnesses or mental health conditions.3 The disorders referred to in this brief include depression, anxiety, PTSD, schizophrenia, autism, or any sort of mental delay.

Mental health services—Any treatment or help for those with mental health conditions. Examples of treatments are counseling, medication, housing/care (such as in a mental hospital), etc.

Ottoman Empire—During the time of the Armenian genocide, this area included Turkey as well as portions of Iraq and Syria.

Psychiatric symptomatology—Symptoms of psychiatric conditions.4

Outpatient clinics—Treatment centers where patients do not spend the night in a mental healthcare facility, but are able to return home after individual treatments are completed with a healthcare professional.5

Schizophrenia—“A serious mental disorder in which people interpret reality abnormally. Schizophrenia may result in some combination of hallucinations, delusions, and extremely disordered thinking and behavior that impairs daily functioning, and can be disabling.” Usually this diagnosis requires lifelong treatment, but the prognosis can be improved if treatments are administered.6

Anxiety disorder—While there are multiple kinds of anxiety disorders, the term can include “feelings of anxiety and panic [that] interfere with daily activities, are difficult to control, are out of proportion to the actual danger and can last a long time.” Anxiety disorders can often be improved with treatment.7

Depression—“A mood disorder that causes a persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest . . . It affects how you feel, think and behave and can lead to a variety of emotional and physical problems.” Also known as major depressive disorder or clinical depression; this condition is usually improved with treatment.8

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—“A mental health condition that's triggered by a terrifying event—either experiencing it or witnessing it. Symptoms may include flashbacks, nightmares and severe anxiety, as well as uncontrollable thoughts about the event.” The condition can be improved with treatment.9

Autism—“A complex developmental condition that involves persistent challenges in social interaction, speech and nonverbal communication, and restricted/repetitive behaviors.” It is also referred to as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and manifests itself differently per each individual.10

Context

Mental Illness

Mental health is vital for the success and well-being of both the individual and society. At the individual level, those with good mental health are able to recognize their intellectual and emotional capabilities to perform to their fullest potential. At a societal level, a community benefits from good mental health as people work in harmony to improve economic welfare.11 Inversely, poor mental health can be a detriment to a society’s social and economic welfare as individuals are unable to reach their full potential, limiting their ability to contribute to society.

Armenia is one of many countries whose population faces mental health struggles to a relatively high degree. However, the extent of these struggles is relatively unknown because Armenia rarely provides recent, updated data on its mental health crisis. There are many factors that may contribute to this, including the fact that many Eastern European nations tend to have less available data and are oftentimes less transparent than their Western European counterparts.12 13 Anecdotal evidence from more recent years indicates that the Armenian mental healthcare system is still flawed, and will thus be used to supplement the lack of recent quantitative studies.14 From an analysis of varying academic and for-profit research, it is estimated that between 10.7% and 38% of the population of Armenia lives with a mental health condition, with the large variation in percentages coming from different data collection methods in the various studies.15 16 Some of the more common mental health conditions in Armenia include depression, anxiety,17 post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance abuse,18 however, conditions such as autism, schizophrenia, and other psychiatric disorders are reported as well.19 The higher estimate of 38% of Armenians suffering from mental health issues is 13% higher than the World Health Organization’s (WHO) universal estimates, which state that approximately 25% of people worldwide have a mental health condition.20

For those who have been diagnosed, mental health conditions seem not to discriminate due to gender within the country. According to Our World in Data, Armenian men and women seem to be evenly affected by mental or substance disorders, at 10.68% and 10.57% respectively.21 However, there are reports of child and adolescent mental health being especially neglected in terms of resources, implying that mental health issues may be more significant for this demographic, as they may be going untreated more often.22

When multiple data sources were analyzed to assess the prevalence of mental health and substance abuse disorders, nearby countries were found to have similar shares of the population with these disorders. Armenia reports that 10.7% of the population has a mental health disorder, while Georgia reports 10.77%, Azerbaijan at 10.46%, and Russia at 11.47%.23 However, Armenia’s numbers provided through the WHO are much lower than those reported by some independent studies. These independent studies examined Armenia’s percentage of mental health disorders by asking Armenians if they knew someone with a mental health condition. Using this method, it appeared that 38% of Armenians had a mental health condition.24 It is recognized that the reported 38% may overstate the number of Armenians that struggle with mental illness since much of the study relied on neighbors reporting neighbors. Additionally, different rates may be reported in the future when researchers use a different set of criteria to establish mental health conditions, or when more in-depth studies are able to reveal a greater number of mental health concerns.

Though mental well-being is clearly an issue in the country, the number of individuals who receive mental health services is low.25 26 Mental health treatment is not often available in Armenia, likely due to the fact that the Armenian healthcare system is highly lacking in mental health professionals, facilities, and additional resources.27 In Armenia, 28% of mental health patients treated in outpatient clinics are those with schizophrenia and delusional disorders.28 29 While estimates from the World Economic Forum suggest that at least 13% of the world population has a mental health condition, diagnosed or undiagnosed, , only 1.2% of the world population,or 13% of those with mental illness, has been diagnosed with schizophrenia.30 31 However, this is a low estimate as other sources depict higher levels of global mental health disorders, which could also indicate a higher level of schizophrenia.32 Thus, those with this mental health condition are disproportionately participating in outpatient treatment, probably due to the severe nature of the disorder.33 Those with milder disorders may avoid treatment altogether and choose to suffer through their conditions due to stigma or a lack of awareness in Armenia of mental health issues.34 Regardless of the reason, many with these other, more prevalent conditions (including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression) are likely not receiving treatment in adequate quantities. Additionally, children and adolescents are disproportionately affected by the lack of mental health services in the country. In fact, when examining the human resources dedicated to mental health, there are only 8 child psychiatrists in the entire country out of 799 mental health professionals.35 Likely due to the lack of child psychiatrists, as of 2009 only 2% of individuals treated in outpatient clinics were children and adolescents with mental illnesses.36 This percentage is especially staggering when compared to the fact that around 30% of all patients treated in outpatient clinics within the United States are children (as of 2018).37

Historical Background

Armenia sits between Europe and the Middle East in the mountainous Caucasus region, which is an area occupied by Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and part of Russia.38 Armenia was the first nation in the world to adopt Christianity as its established religion, creating conflicts with non-Christian nations such as modern-day Turkey, which led to the Armenian genocide of 1915–1917.39 During the Armenian genocide, which is regarded as one of the largest examples of ethnic cleansing in history, an estimated 1.5 million Armenians were killed by the Ottoman Empire.40 41 It is documented that mass murders, rape, and torture were extremely prevalent, yet the Turkish government has continuously denied responsibility for the genocide and has yet to acknowledge that it even happened.42 As of 2020, Turkey has absolved themselves of any deliberate genocide, scapegoating common criminals in order to label mass killings as a security mishap, and using political pressures to silence journalists or any outspoken individuals from revealing the truth.43

The mass eradication of Armenian people and Armenia’s abrupt transition into a socialist state soon after the genocide shifted the country in unprecedented ways. When the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was formed in 1922, Armenia became part of the Trans-Caucasian Soviet Socialist Republic.44 Armenia was part of the USSR until 1991 and subscribed to the ideals of the widespread socialist state.45 One of the ideologies promoted was that of “no invalids in the USSR”—the term invalids included those with mental illness, as well as those with physical disabilities.46 This a common belief even today, as individuals with mental health issues are often hidden out of sight in domestic and societal settings.47 Living conditions in mental health hospitals were extremely poor during the Soviet era as there was little acknowledgement of or sympathy for psychologically disabled individuals. It has also been documented that these Soviet-controlled mental hospitals were ridden with inhumane practices that disempowered patients.48 In Armenia, similar practices and treatment of those with mental health conditions continue because of the lingering societal stigma from the Soviet-controlled era.49

This brief focuses both on issues that bring about increased rates of mental illness and on issues that contribute to poor management of mental illness in Armenia. As such, the Contributing Factors and Consequences will address both these factors. The Contributing Factors Historical Trauma and Domestic Violence address why mental health conditions are prevalent in Armenia. The subsequent Contributing Factors, Cultural Stigmas and Lack of Resources & Inadequate Healthcare Infrastructure, examine how Armenia is failing to address the widespread issue of mental health.

Contributing Factors

Historical Trauma

Armenian Genocide

The Armenian genocide, has left a more severe impact on mental health than any other event in the Armenia’s history due to the residual genetic trauma that has been passed down from genocide survivors to their descendents. Scholars and the media alike are left unsure how widespread the effects of the genocide were, since those affected were not just those who died but also those who witnessed Turkish brutality and the elimination of so much Armenian culture.50 The intense trauma that was inflicted on Armenians at the time would have likely caused mental health problems for those who were present during these events, although there is no data on first generation survivors of the Armenian genocide specifically. Comparatively, studies conducted about the effects of the 1994 Rwandan genocide show that 30% of the mothers who lived through that genocide fit the diagnostic criteria for PTSD.51 Though these numbers are not exactly representative of the Armenian population, it can be assumed the rates would be similar in Armenia due to the similarities in the trauma inflicted. Additionally, studies indicate those who experience trauma often show symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for approximately 1–13 years following the traumatic incident, depending on the type of trauma they experience.52 Some will experience PTSD for the rest of their lives.53

In additon to the trauma that was inflicted during the Armenian genocide, the lack of acknowledgement and awareness of the genocide for over a century, coupled with the lack of recognition of the mental health issues it caused, has now evolved into generational mental health issues among the descendants of those who survived these events. As it is difficult to determine who was affected by the genocide while it was occurring, it is also difficult to determine who the descendants of those people are now.

One Armenian psychologist classified a prominent mental health condition within Armenia as “hidden anxiety,” or “post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with delayed onset.” This condition is predominantly due to personal experience with the Armenian genocide as it is related to genetic inheritance.54 An epidemiological study showed that environmental factors such as stressful life events and childhood stress have heritable characteristics, which means an individual that experienced such circumstances is more likely to pass on the mental disorder caused by that traumatic event to their children.55 This phenomenon is amplified in Armenia due to the number of traumatic events that occured in the region. A 2018 study found that having a lineage to a known direct Armenian genocide survivor led to higher overall PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores, with participants who had more than 4 genocide survivors in their ancestrial line having an average PHQ-9 score of 8.55, compared to individuals who had zero survivors having an average score of 5.75.56 In a study on Holocaust survivors, it was concluded that symptoms of depression in the second generation were a result of the circumstances of the parents’ survival. It was also found that anxiety disorders , the term can include “feelings of anxiety and panic [that] interfere with daily activities, are difficult to control, are out of proportion to the actual danger and can last a long time.” Anxiety disorders can often be improved with treatment.">Anxiety disorders were more common in descendants of genocide survivors.57 Though these conclusions were based on Holocaust survivors and not survivors of the Armenian genocide, similar conclusions can be made for Armenians as well.

Earthquake

On December 7, 1988, one of the most damaging earthquakes of the past century hit Armenia. With the tremor lasting almost a minute long with a magnitude of 6.9 on the Richter scale, four cities and 350 villages in Armenia were destroyed.58 This catastrophic event killed about 100,000 people, with 530,000 people left homeless.59

In March of 1989 (three months after the earthquake), 62 people out of a sample of 65 Armenians examined in Yerevan (the capital of Armenia) were said to have been suffering from PTSD. Of these individuals, 15% were also said to be struggling from major depressive disorders.60 The worry at the time was that, if left untreated, the victims may develop long-term Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or other issues such as alcoholism, job instability, and violent behavior.61 The traumatic events of the earthquake, the inability of the still Soviet-controlled government to adequately recover from the damage the earthquake left on its citizens, and a lack of mental health support subsequently led to greater rates of mental health issues and an impaired ability for individuals to fully recover from their damaged mental states.62 This stems from the stigma associated with mental health conditions, which manifests itself as a lack of access to mental health resources and support from surrounding communities.

A study administered to 200 members of 12 multigenerational families impacted by the 1988 earthquake found that individuals with ancestors affected by the earthquake were more vulnerable than others to develop symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression. Out of the 200 individuals 41% showed PTSD symptoms, 61% showed anxiety symptoms, and 66% showed depressive symptoms.63 Thus, untreated trauma from previous generations has been shown to be passed down to descendents. With there being more descendants than initial survivors, the rate of mental illness compounds, creating further, more widespread mental health crises within the country.

Domestic Violence

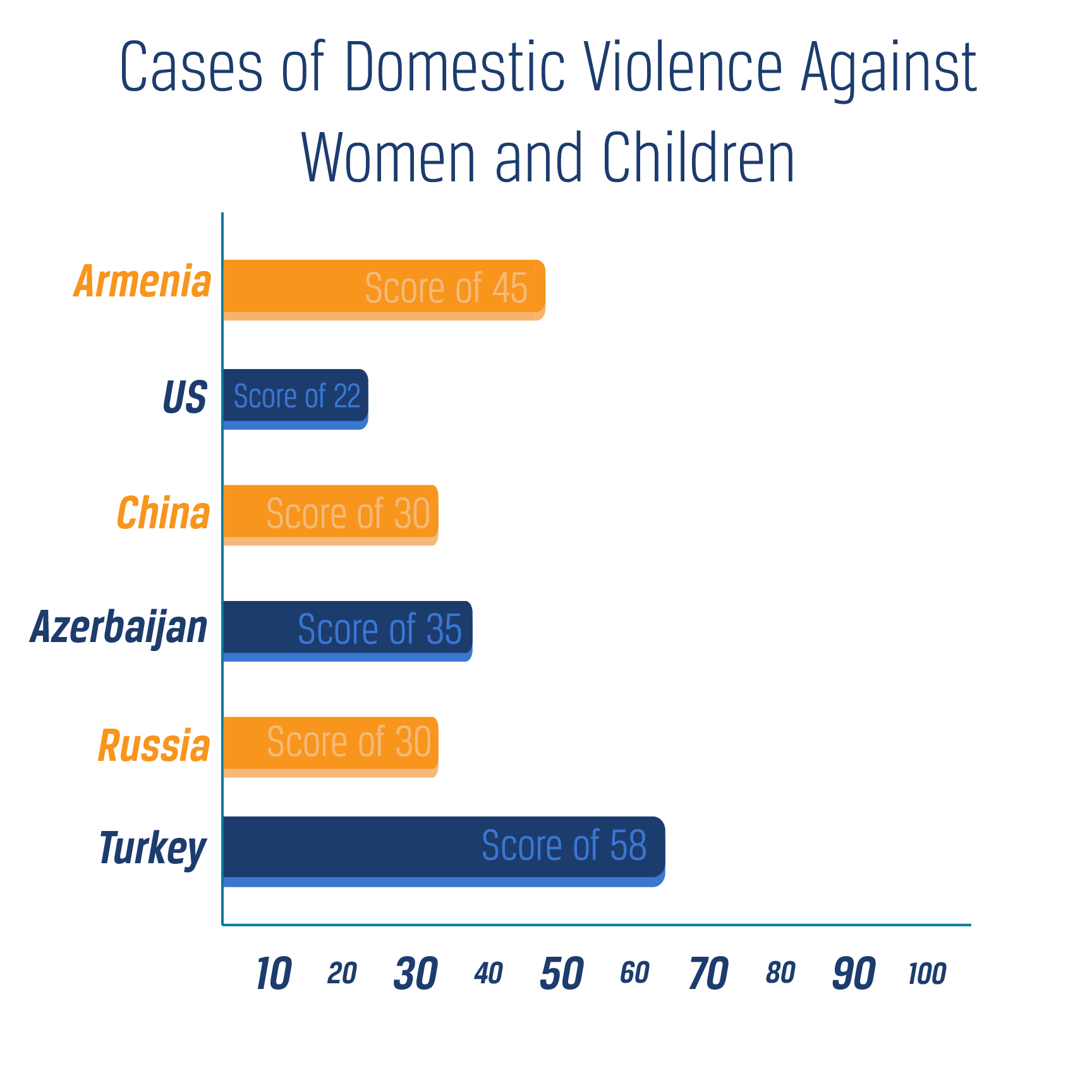

Not only have traumatic incidents in the past contributed to mental illness in Armenia, but the ongoing, unaddressed issue of domestic violence is also perpetuating poor mental health conditions within the country. In 2019, it was reported that a quarter of married women in Armenia have suffered from domestic violence.64 Though numbers for domestic violence are difficult to obtain, the WomenStats project reports a score of 45 (with 1 being least number of occurences and 100 being the most) for cases of domestic violence against women and children in Armenia.65 Comparatively, the US was given a score of 22 and China a score of 30. Azerbaijan, another Caucasus country, was given a score of 35, Russia a score of 30, and Turkey a score of 58, indicating that Armenia exceeds most of its neighbors and a significant number of other countries around the world, but not all of them.66 However, only 3.5% of Armenian women have reported cases of physical or sexual violence, likely due to societal stigma or ineffective laws protecting against domestic violence.67 68

Although studies on the correlation between domestic violence and mental health concerns in Armenia are lacking, an Israeli study on the same relationship concluded that Israeli women who had experienced domestic violence exhibited 52% higher levels of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and psychiatric symptomatology compared to women who had not reported domestic violence.69 Research also indicates that the most common mental health disorders associated with domestic violence are depression and PTSD.70

While many other countries have laws protecting individuals from domestic violence, Armenia’s laws regarding this subject are lacking. Before 2017, there were no laws specifically prohibiting domestic violence.71 Now, Armenian laws emphasize maintaining the family structure rather than maintaining safety for individuals within that family.72 For example, victims may be told that the abuse was a consequence of their own behavior and that they should seek to repair their relationship with the perpetrator rather than officially document the incident as abuse.73 If a victim actually does report a case of abuse, the law for domestic violence cases is structured so there are minimal consequences for the abuser until the third report of abuse. The abuser and victim are also called together in court where they are encouraged to work out their differences in order to maintain a stable family unit.74 During the court hearing, the maximum punishment possible for the abuser is a six month prohibition on communication with the victim, which can be extended up to six additional months.75 According to anecdotal accounts, authorities often do nothing to protect the victims, prevent additional cases of abuse, or even direct individuals to services that would help them recover from abuse.76 Facing their problems alone and with the pressure to maintain dangerous familial situations could promote mental health issues that are going undiagnosed and untreated.

Cultural Stigmas

A significant number of Armenians with mental health conditions are not aware of their condition, are not reporting it, or are not seeking treatment for it due to the negative stigma associated with psychiatric disorders in Armenia. These stigmas are especially prevalent for children and men. For example, rather than admit a child into a psychiatric ward for treatment, Armenian parents are often inclined to hide the child away for fear of bringing shame upon their family. Some even believe that mental illness is a punishment from God rather than a medical condition that can be resolved with treatment.77 These myths have encouraged maltreatment of and violence against children with mental disabilities.78 While educational programs have helped to curb the violence, their implementation has been experimental and limited.79 It is also common for men of Armenian descent to not seek treatment due to actual or perceived stigma attached to the Armenian community and culture.80 According to a therapist of Armenian descent, “The idea of paying someone for ‘advice’ runs counter to centuries of self-reliant individualism and may even be considered shameful or dishonorable.” He goes on to say that it would take an extreme situation, often including outside pressure, to encourage Armenian men to participate in psychotherapy.81

According to a study conducted by Doctors Without Borders, 63% of Armenians believe that those with mental illnesses are dangerous and 56% believe that they should be kept in hospitals.82 This could be due to the fact that mental illness is often viewed as untreatable in Armenia.83 If individuals are not seen as capable of recovering or having their condition improved to any degree, society will not provide opportunities to encourage those kinds of outcomes (as evident by the lack of mental healthcare facilities).84 Those individuals would not be seen as being as equally capable as those who do not live with mental health conditions. According to mental health professionals, more work needs to be done to ensure that the public sees individuals with mental health conditions as capable and having potential.85 The fact that this assumed potential is not already prevalent encourages the idea that being mentally ill is a social barrier for both working and living a typical life within Armenia.86

Lack of Resources & Inadequate Healthcare Infrastructure

The lack of mental health resources, especially community-based resources, perpetuates the prevalence of mental health conditions among the Armenian population because individuals are not able to recover from or improve in their conditions.87 Armenia’s healthcare is still relatively centralized and designed to provide free healthcare for disadvantaged groups as a result of their previously communist society. However, those centralized medical facilities are not receiving enough funds from the government to pay for all necessary medical treatments and personnel. To compensate for a lack of funding from the government, many healthcare practices have become privatized, and thus more expensive for patients.88 Thus, some may not be able to afford the additional expense of mental healthcare on top of “under-the-table fees” for the underpaid healthcare professionals.89 90 91 While these additional expenses are not addressed by every source, there is some evidence to suggest their existence.92 93

When healthcare professionals are not paid, the industry shrinks, despite a need for mental healthcare within the country.94 According to the WHO, as of 2017 there were only 3.84 psychiatrists per 100,000 individuals within Armenia.95 In a country of roughly three million people, this statistic equates to about 115 psychiatrists supporting the entire country’s population.96 The state of Kansas in the United States has a similar population to that of Armenia (roughly 2,910,357 people to Armenia’s 2,965,56697 98) but has 431 psychiatrists, which is still considered to be a shortage by U.S. standards.99

However, the situation is even worse for specialized professionals in Armenia, with .27 child psychiatrists, .79 psychologists, and .27 social workers per 100,000 people.100 That equates to about 8 child psychiatrists, 23 psychologists, and 8 social workers supporting the entire country’s mental health needs. As of 2009, there were no psychiatrists within the country who had undergone mental health training that lasted more than a year.101 Additionally, 20% of newly educated psychiatric specialists leave the country within five years of completing their education.102 Those who are still practicing in the country, according to the standards of their time and area, usually have resources and practices that were promoted in the Soviet era, which are outdated and less effective.103 104 105

While there are psychiatric hospitals in the country, they are inadequate in providing for the needs of the Armenian population.106 As of 2009, 40% of the outpatient facilities that did exist within the country were dedicated to children, but only 2% of children were able to be treated, highlighting the need for either additional facilities or, as stated previously, less stigma surrounding the issue so that more children could have access to this resource.107 108 However, approximately 8 years later in 2017, there was only one outpatient facility dedicated to children, with 40 provided for the general population (with 2.4% of the facilities being dedicated to children).109 As a result, there is now even less of a focus on treating children than there was when only 2% of all Armenian children were receiving treatment. While having more facilities for the general population is an improvement, it may mean a decrease in facilities that emphasize children’s mental wellbeing.

Consequences

Human Rights Violations

Though outpatient clinics have become increasingly more common as a resource for mental health treatment in Armenia, mental hospitals continue to be the main treatment option.110 111 112 Many of these institutions are reported to be riddled with human rights violations, including the intimidation, starvation, and seclusion of patients by staff members, though many who run the hospitals deny these claims.113 According to a study conducted by a human rights organization in Armenia in 2018, workers beat patients in front of others, hospitals utilized illegal drugs to sedate patients, and the hospitals stored expired drugs, which could be used on patients despite being either ineffective, dangerous, or both.114 In 2017, the UN concluded that the norm for mental health practice in Armenia was to hospitalize an excessive number of patients (including those that could benefit from less intensive outpatient treatment), overmedicate them, and keep them for excessive amounts of time without the hope of their condition improving, i.e. unnecessarily labelling them as chronic.115 This treatment persists as there is no national or regional human rights review body that regularly inspects patient human rights violations. In fact, the Armenian Ministry of Health has no authority to impose sanctions for proven human rights violations.116

When asked to describe her experience in a mental institution, one schizophrenia patient reported that she “lived in hell.” After returning home, the patient’s mother reported that her daughter would “hide her head in her hands every time somebody made a sudden movement.” If the daughter ever accidentally broke something, she would “[turn] pale and [look] at [her mother] horrified.” These are all behaviors that did not occur before hospitalization and provide evidence of probable mistreatment and abuse.117 On some occasions, individuals are not allowed visits from family members or friends when in the mental hospital. This could be due to the fact that hospitals receive more money for each patient they admit, giving them an incentive to “treat” as many people as they can, regardless of whether they need treatment, and visits may lead to the discovery that not all admitted patients actually need to be there.118 By not allowing visitations, no one is able to advocate for patients who are being improperly cared for or are experiencing human rights violations from hospital staff. Because of a lack of reporting and quantitative data on the issue, these anecdotal pieces of evidence only highlight some examples of corruption and dehumanization that occurs within the mental healthcare sector of Armenia.

Additionally, mental institutions are used as tools to take advantage of other Armenians who do not have mental health disorders, rather than treating those who do. It is estimated that in the Soviet era, roughly a third of political prisoners were housed in mental institutions under allegations of madness.119 Legal and anecdotal evidence suggests that this behavior continues today, but often with regards to family disputes.120 The extent of this practice is unclear, but according to the head of an Armenian human rights organization, “A person might be completely healthy but just one phone call from relatives, neighbours or someone else who has a grudge against them could lead to them being picked up by police and locked up in a psychiatric institution indefinitely.”121 If an individual refuses to report to the mental health facility, their case can be taken to court, where the individual will not receive legal representation. Individuals who are incorrectly accused of mental illness can find themselves enduring unnecessary trauma in a place where only relief from suffering should be administered. Thus, because Armenia does not view mental healthcare as a priority, it is being used as a weapon, rather than an aid to assist a struggling population.

Lack of Economic Mobility

With both the prevalence of mental health conditions, the lack of effective treatment options available, and the stigma against the mentally ill, news of having a psychiatric condition could prove disastrous for one’s economic life. In order to obtain a driver’s license or to work for the government, one must go through a psychiatric examination.122 If, during this examination, one is revealed to have a psychiatric condition, that information is recorded on his or her permanent record, making it harder to be hired in the future and harder to travel to current employment if one is denied licensure.123 Thus, being found to have a mental illness can ruin an Armenian’s economic standing, even today in the 21st century.

Those suffering from severe mental disorders may also face increased difficulty in performing their jobs effectively. Since Armenia lacks enough high-quality resources for those with mental health conditions, individuals are not acquiring necessary assistance that could help them to better maintain jobs or move higher up the economic ladder. In the United States, a PHQ-9 score of 7 or more can result in anywhere from 29.6–51.3% lost productivity within a week, which is anywhere from 21.6–43.3% more unproductive time than those without a mental health disorders.124 As subjects receive treatment for depression, their PHQ-9 score decreases, thus increasing their job efficiency.125 If the productivity data can be extrapolated for Armenia, this would mean that those with depression would be more productive if they experienced fewer symptoms of mental illness. Without adequate treatment they are less productive in their workplaces than they otherwise could be. This limits the economic mobility of the individual as well as the country as a whole.

Although individuals with untreated mental illness may be less productive than the average worker, some Armenians may exaggerate those inefficiencies due to bias against mental illnesses. According to a Doctors Without Borders survey, 54% of Armenians believed that those with mental health problems “cannot do any work” and 53% reported that they would be “upset or disturbed working in the same job as someone with a mental illness.”126 127 This perpetuated stigma is economically repressing individuals with mental health conditions. If one believes that an individual with a mental health condition cannot be a productive member of society, that individual would have a difficult time fighting against those preconceived notions. Thus, they are running at a deficit in terms of the economic playing field when the public does not give them a chance to succeed in the workforce.

Due to the mental health stigma which makes it difficult for those with mental health conditions to hold a job in Armenia, there is a correlation nationwide between individuals having a mental health condition and experiencing homelessness within the country.128 While the connection between mental illness and homelessness is not unique to Armenia, it could be exacerbated by the number of mental health cases that are not being treated within the country. Not only are some individuals not receiving the psychological care they need, causing them to be more likely to lose their homes due to financial instability, but the only homeless shelter in Armenia, Hans Christian Kofoed, has been instructed by the government not to admit those with mental health conditions in order to maintain the safety of the other inhabitants of the shelter.129 130 Thus, although the shelter estimates that there are 400 homeless individuals in the capital city of Yerevan alone, it currently only has the capacity to shelter a fourth of that population, with the mentally ill being perpetually in the excluded group.131 According to Armenian “law on social assistance,” people housed cannot include individuals with certain mental illnesses, along with those that have tuberculosis, skin diseases, Hepatitis C, and STDs.132 Additionally, a social worker at Kofoed attributes some of the homeless mentally ill population to families who evict those relatives due to the mental health stigma.133 While the mentally ill are continuing to be barred from economic aid afforded to others within the Armenian community, they will continue to be disadvantaged in terms of economic mobility.

Harm to Interpersonal Relationships

Stigma regarding mental health conditions can have long-term effects on the stability of a family and the maintenance of other social relationships. In a survey conducted by Doctors Without Borders, 56% of Armenians believed that they would “not be able to maintain a friendship with someone with a mental illness” and 63% believed that those with mental illnesses “are usually violent and dangerous.”134 As there are not many individuals willing to form meaningful connections with those with mental illnesses, they can become isolated and emotionally uncared for. As stated above, if one is found to have a mental illness, their family members may disown them for fear of harboring a crazy person in their home. Thus, they may be forced into the homeless community and thereby ostracized from the rest of society.135

In addition to the stigma associated with mental health conditions, mental illness itself may result in family and social instability. If left untreated, which it often is in Armenia as a result of this stigma, the mental illness of a parent can also have negative outcomes on children. Certain circumstances such as “poverty, occupational or marital difficulties, poor parent-child communication, parent’s co-occuring substance abuse disorder, openly aggressive or hostile behavior by a parent, [and/or] single-parent families” can increase a child’s risk for “social, emotional and/or behavioral problems.”136 These situations are often more common in families with untreated parental mental illness. These parental mental illnesses may make it more difficult for children suffering from social, emotional, or behavioral problems to receive the help and support that they need.137 The instability that may be associated with untreated parental mental illness can force children into a pseudo-parental role for themselves and any younger siblings, hurt their academic and social lives, damage their emotional health, and put them at risk of developing mental illness themselves.138 139 With proper treatment, however, parents can overcome their mental health challenges and provide a safe and healthy home environment for their children. 140

Spousal relationships can also be strained by untreated mental illness. Global research demonstrates that if one partner has a mental illness, the rate of divorce increases, and the rate becomes even higher if both partners have a mental illness.141 This is partly because mental illness can increase social tension between spouses. However, familial strife does not have to be the standard for those with a mental illness; interpersonal relationships can still flourish if one is able to overcome societal stigma and seek treatment.142

Practices

End the Stigma Through Educating Professionals & the Public

Proper education is crucial to ending the stigma around mental health issues in Armenia. Education in terms of mental health includes addressing false, commonly-held conceptions and replacing them with their factual counterparts.143 In Armenia, specifically, education could potentially show citizens the humanity of those with mental illness and that a mental health condition is not a punishment from God but a medical condition that can be treated.144 If those with mental illnesses were accepted within society, better resources and opportunities could be provided for them. Additionally, recognizing the humanity of the patients would enable client-centered rather than staff-centered care, which would improve the quality of life and the prognosis for those with mental health conditions.145 These better resources combined with less social shame would enable more people to seek legitimate help for mental health problems without fear of serious, long-lasting repercussions.

Sanofi, a global healthcare organization, launched a branch of its mental health program in Armenia in 2017. This branch is called Fight Against STigma (FAST).146 Partnering with the Armenia Ministry of Health and the World Association for Social Psychiatry, their goals included improving “diagnosis, treatment, support, and referral” for those with schizophrenia and/or depression.147 To achieve this, the organization provided in-person training for mental healthcare professionals, training materials, and a patient recording system to keep track of patients receiving treatment.148 They also provided education to decrease the public stigma associated with mental illness by providing materials such as posters, brochures, flipcharts, and comic books to raise awareness among the population.149

Impact

Although there are no output, outcome, or impact statistics available to demonstrate the effectiveness of the FAST intervention, Sanofi does report various goals that they hoped to achieve by 2019. These goals included training 600 general practitioners and 200 nurses on diagnosing and caring for those with schizophrenia and depression, training 180 other medical personnel not specialized in mental health on depression, host follow-up training sessions on depression for 120 mental healthcare workers in the form of five one-day sessions, and generally raise public awareness of mental illness.150

Although Sanofi has not reported whether these goals were reached, some studies conducted in other countries on the effectiveness of public mental illness education programs have shown that educational interventions can succeed in decreasing the stigma against those with mental illness.151 For example, in Scotland, the Scottish campaign titled “See Me,” resulted in an 11% decrease in the public belief that protections should be enabled against those with mental illness and a 17% decrease in the belief that those with mental illnesses are dangerous.152 This indicates that similar results may have occurred in Armenia as a result of the FAST program, but without any numeric indicators, one cannot be certain that FAST had any lasting influence, positive or negative.

Gaps

The Sanofi FAST program had good intentions, but there were some gaps in its structure. First, while the actual dates of the program’s implementation are not clear, it is likely that it was only meant to be temporary. Any facets of the program dedicated to educating the public against the mental health stigma may likewise be temporary. If this program had a positive impact on the Armenian community, the stigma may resurface after those education efforts have subsided. Additionally, even if the goal numbers were met, they would not necessarily mean that the program was successful in achieving its aims; just because materials are in circulation does not mean the materials are doing any good for those with mental illness or the Armenian community in general. Lastly, the FAST program was not developed specifically for Armenia and its citizens, making the program potentially less effective than it could be.153 In conclusion, while the program had positive intentions, there are definitely areas that could be improved upon which would likely better help the Armenian people.

Increase Access to Treatment

Mental health services are interventions that help treat an individual's mental health condition, reduce symptoms, and improve behavioral functioning and its outcomes.154 Upon an individual coming to a mental health facility (psychiatric hospital, separate inpatient psychiatric unit of a general hospital, residential treatment center, day treatment, or outpatient), there will be a mental health intake. This intake includes evaluations that measure the type and degree of the patient’s condition to determine whether the patient needs treatment, and if recommended for treatment, the most appropriate service for their diagnosis. From then on, the patient will be enrolled in a treatment that is specifically applicable to their illness, including psychotherapy, medication, psychological treatments, and complementary health approaches.155

Open Society Foundations Armenia’s (OSF) Public Health Program advocates for health policies and practices that are grounded in evidence and look to promote access to palliative care.156 This form of treatment is designed to improve the quality of life for both patients and their families by relieving the symptoms, stress, and pain that comes along with a debilitating mental illness. Palliative care is most often provided by a team of medical professionals at the onset of a diagnosis. These physicians, nurse practitioners, and registered nurses will recommend services under the umbrella of palliative care which include minimizing pain and discomfort, alleviating emotional distress, assisting with mobility and equipment, providing spiritual counseling, and empowering patients and caregivers to make the right decisions when it comes to their mental health.157

Impact

There is no specific impact data for OSFA, and due to poor data collection on Armenian mental health services in general, it is difficult to determine what the impact of OSFA has been. The Armenian government has increased the amount of money dedicated to mental health; in 2009, only 3% of health expenditures were devoted to mental health,158 whereas in 2017 up to 19.6% were dedicated to mental health.159 However, most of those expenditures go towards inpatient mental health hospitals. This illustrates that, although there is more funding dedicated to mental health currently, there is still a need for community-based interventions.160 In this regard, the presence of community mental health services is likely beneficial for those in the community. However, the lack of any data makes this suggestion an inference and not a fact.

Gaps

Gaps that underlie both the Armenian government, international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs), and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) alike are that there are not enough resource allocation for outpatient services (versus inpatient services). Additionally, there are a very few number of educated psychiatrists in the mental healthcare system, who have the educational and professional background to accurately prescribe medication. Along with educating more professionals, nothing can ultimately be done to increase access to medication unless the stigma against medication is dismantled. This can be done through educating the public and mental health professionals on the benefits of prescribed medication and the ramifications of leaving mentally ill patients untreated. By erasing this stigma, Armenians will be able to access medication more freely, not feeling judged by community or mental health professionals for wanting to improve their mental well-being. The Armenian government also needs to align themselves with NGOs who are working in smaller communities, so individuals can gain easier access to treatment without having to be institutionalized. Lastly, those practices that are being implemented by OSF are focused on palliative care. This type of care does not assist in treating an illness, but in primarily making individuals comfortable while living with that illness. Thus, this is a step in the right direction, but not a solution to the lack of mental healthcare in the country.

Decreasing Human Rights Violations through Deinstitutionalization

Deinstitutionalization in the context of mental healthcare refers to providing other mental health resources besides institutionalization to individuals with less-severe mental illnesses.161 As Armenia has a history of over-institutionalizing their patients (as of 2017, 64.3% of individuals in Armenian mental institutions lived there for more than five years), this process would ideally provide more effective and better quality treatment for individuals with more minor mental illnesses.162 163 In an assessment of one of the large care homes in Armenia, Vardenis Neurological and Psychological Boarding Home, 103 residents out of 438 residents were shown that they no longer needed to stay in such an intensive boarding home and could instead be moved to a smaller care home of 3 people or a residential home of 10 people maximum.

In regards to care homes, the government enforced decree N 1533-N which outlines the goals of alternative community care services. Some of these goals include having those with psychological disabilities living independently and being integrated into the community. These goals also include providing social support from home care personnel to make mentally ill individuals feel safe and cared for. The responsibilities of these home care professionals are also laid out in the policy document to ensure adherence to the integration of mentally ill individuals into community based living.

Since 2011, the Armenian government has made steps to transfer the mental health system from treating patients in institutionalized facilities to assisting mental ill individuals at the community level. One step includes a collective working group (psychiatrists, psychologists, and NGO representatives) of the Armenian Ministry of Health working alongside OSFA to draft their first mental health policy. Some action items in this list include Armenian government collaboration with the Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities, training of specialists, design and implementation, and a community-centered mental health care project. By demonstrating that at least some individuals with mental illness could have needs that are better addressed in outpatient clinics, rather than in institutions, these programs encouraged deinstitutionalization. In addition, while the working group was still developing policy in 2013, the Armenian government adopted an action plan to examine alternative care methods and social services such as community based interventions for people with mental illnesses. Both of these pieces of legislation adopted in 2013 and 2014 have moved the Armenian government forward to deinstitutionalize mental health care for those who need it.

Analysis

It is unclear what action has actually been taken regarding recent mental health legislation. The data that is available is sparse and does not indicate an impact, whether positive or negative. Some output and outcome data has been recorded, however, that may be associated with deinstitutionalization-specific governmental legislation. The first is that dual-type care home services of up to 8 and 16 people (in two separate areas) were approved by the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs to integrate mentally ill individuals into community living. This ensured they had the chance to carry out basic activities in everyday life, participate in community based events, and make meaningful interpersonal relationships. The second potentially related deinstitutionalization step is that of a pilot project implemented in Spitak City in 2016 that assisted 10 people in moving out of a large institutionalized mental health facility to a home care facility. This new facility has benefited from collaboration with the human rights organization, Helsinki Citizen’s Assembly Vanadzor, providing legal counsel, training and awareness on human rights issues to the residents and employees. This shift toward giving institutionalized patients a place to live within a community, while also giving information on how and why Armenia needs to integrate these people into a community shows a great leap forward in reducing human rights violations through deinstitutionalization. However, because no experiments (such as randomized control trials) were conducted to determine the origin of this progress, it is impossible to say whether these improvements were caused by this legislation, or whether this legislation is causing any change whatsoever.

Based on conditions in 2020, there are a few potential barriers to successfully implementing the practice of deinstitutionalization including organizing, building, staffing, and running community care facilities that are not yet common in-country. While these facilities still need to be organized, another barrier to deinstitutionalized mental health care includes the integration of patients into these facilities. For those that currently live in institutionalized care centers, it will take convincing of medical professionals and select government leaders that more patients need community centered care. Until the mental health stigma is addressed, it will be a barrier to extensive creation of outpatient facilities. Additionally, the overall lack of mental healthcare professionals (psychologists, psychiatrists, etc.) prevents the widespread implementation of successful mental healthcare, including outpatient clinics.164 Lastly, it will likely be expensive to implement deinstitutionalization with more medical professionals needing to be hired and facilities constructed. If there are not enough resources, no amount of restructuring will be able to adequately provide for the needs of all of Armenia’s mentally ill (although some improvements may be made in quality of care).

Preferred Citation: Rushforth, Morgan and Sara Jensen. “Mental Health Concerns in Armenia.” Ballard Brief. January 2021. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints