Mental Illness Among Adolescent Refugees in the United States

By Kate Lloyd

Published Winter 2019

Special thanks to Marissa Getts for editing and research contributions

+ Summary

As the worldwide refugee population has steadily increased over the past decade, mental health concerns among refugees have become more prevalent. In the United States, adolescent refugees face higher rates of mental illness in comparison to non-refugee adolescents. Mental health concerns stem from traumatic experiences, challenges with acculturation, discrimination from peers, separation from parents, and cultural perceptions of mental illness in refugees' country of origin. As a result of these traumatic experiences, adolescent refugees are at a higher risk of mental illnesses such as PTSD, depression, and anxiety, creating barriers to their ability to smoothly transition into the United States. In order to address the problem of mental illness in adolescent refugees, current practices focus on intervention in schools, promising therapy techniques, and cultural awareness education of mental health providers.

+ Key Takeaways

+ Key Terms

Refugee—The 1951 Refugee Convention defines a refugee as “someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.”1

Mental Illness—The American Psychiatric Association defines mental illnesses as “health conditions involving changes in emotion, thinking, or behavior (or a combination of these). Mental illnesses are associated with distress and problems functioning in social, work, or family activities.”2

Acculturation—Acculturation is defined as the process by which a refugee adopts the cultural behaviors of their host country, which leads to changes in diet, physical activity level, and environmental exposures.3

Adolescent—For the purposes of this paper, adolescents refer to youth between the ages of 11-18.

Unaccompanied Refugee Minor (URM)—This refers to children under the age of 18 who come to the United States without at least one parent and also hold one of the following statuses: refugee, entrant, asylee, victim of trafficking, Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, or U visa holders.4

Trauma—In general, trauma can be defined as a psychological, emotional response to an event or an experience that is deeply distressing or disturbing.5 Refugee trauma refers to the experiences refugees face prior to resettlement, including violence (as witnesses, victims, or perpetrators), war, lack of food, lack of water, lack of shelter, physical injuries, infections, diseases, torture, forced labor, sexual assault, lack of medical care, loss of loved ones, and disruption in or lack of access to schooling.6

Context

Ongoing violence worldwide has forced millions of people out of their home countries. In 2017, an estimated 16.2 million individuals were newly displaced refugees worldwide.7 Of those 16.2 million displaced refugees, 53,716 were resettled in the United States, or approximately 3% of all refugees. More than half of resettled refugees were under the age of 18.8 Due to the high volume of refugees in the past decade, the United States has been required to increase its understanding of the unique needs refugees face in order for the United States to be able to better support refugees.

The United States has a long history of refugee resettlement, starting with resettlement efforts during World War II. Post World War II, the United States settled over 400,000 European refugees.9 The tradition of resettlement continued throughout the next decade, as the United States accepted refugees from the former Soviet Union, Southeast Asia, and Cuba. The current refugee crisis is centered on the conflict in Syria, which began in 2011. Of the 5 million refugees who have left Syria since 2011, only 62 Syrian refugees were admitted to the United States in 2018.10 Although in the past the United States has resettled over 50,000 refugees per year, only 30,000 refugees were resettled in 2017 and only 22,000 were resettled in 2018.11 The median time spent in refugee camps prior to resettlement is 4 years.12 Recent stats from UNHCR reveal that 68% of refugees resettled in the United States come from just 5 countries: Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Myanmar, and Somalia (see Figure 1).13

Figure 1

After arriving in the United States, refugees are resettled through affiliate programs from one of the following 10 placement programs: Church World Service, Episcopal Migration Ministries, Ethiopian Community Development Council, HIAS, International Rescue Committee, Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, or World Relief. These organizations resettle refugees in compliance with the regulations from the Centers for Disease Control and prevention (CDC) and the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). The ORR requires a health screening in the first 90 days; however, there is a lack of procedural or financial support for mental health screening for refugees.14 According to a report from 2010, only 4 out of 44 states employed proper health screening techniques, and 68% used informal conversation as a form of screening.15 Further, screening of mental health in refugee camps is often conducted by interviewers with little training. Special protection and consideration for traumatized individuals may be overlooked due to the interviewer's inadequate methods.16

Prior to resettlement in the United States, refugees face a wide variety of challenges. Typically, refugee status is offered to individuals identified by the UNHCR as “most vulnerable,” such as women and children, the elderly, survivors of violence and torture, and those with acute medical needs.17 After refugees travel long distances from home to new countries, refugees may struggle to adjust to the culture. Traumatic life events such as exposure to war, torture, internment in refugee camps, rape, human trafficking, and loss of family may lead to psychological stress. Additionally, once refugees are in the United States, the stress of adapting to a new culture, low socioeconomic status, and unemployment may affect mental health.18 According to the Refugee Health Technical Assistance Center, PTSD and major depression in settled refugees range from 10–40% and 5–15%, respectively, based on several studies.19

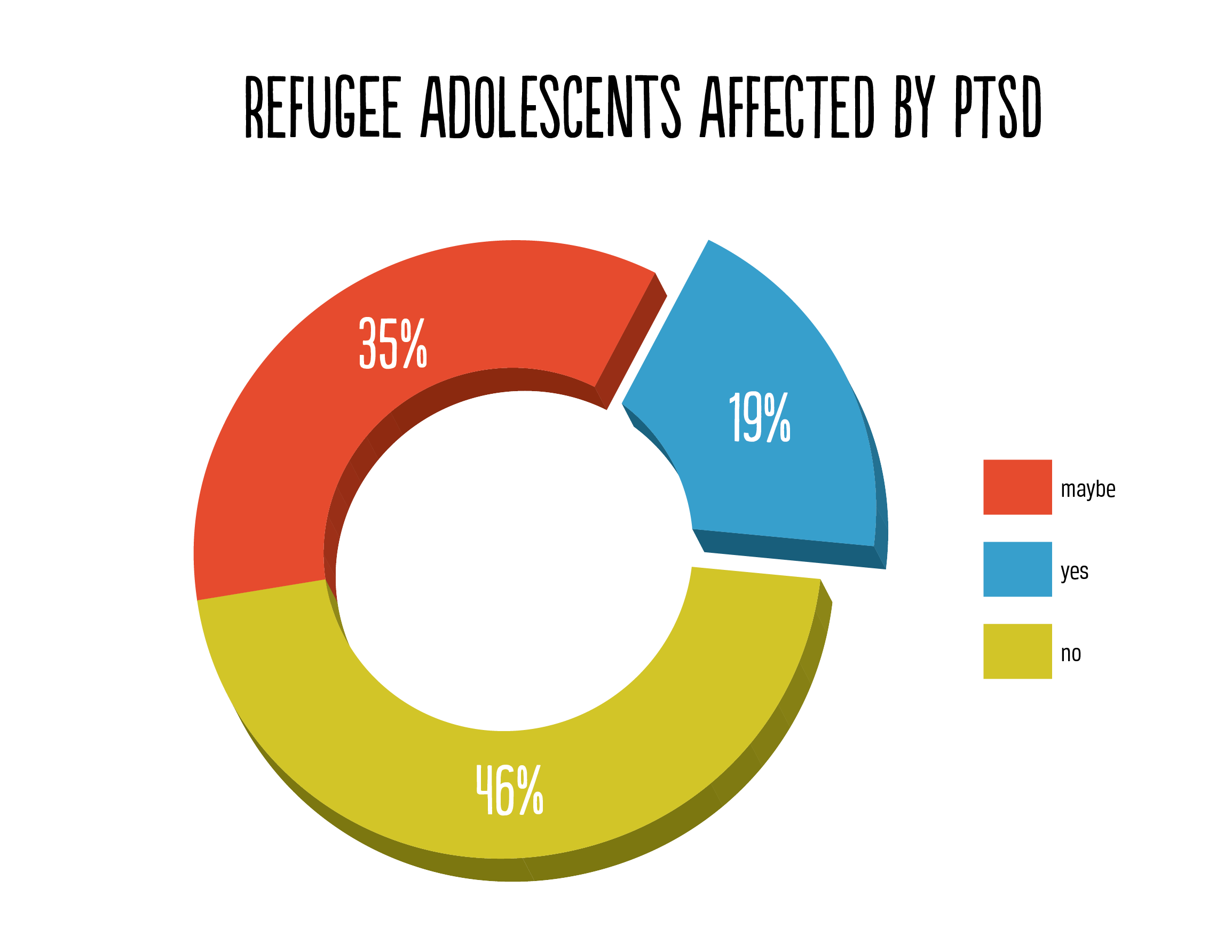

Although the onset of mental illnesses can occur at any age, the typical age of onset occurs in the late teens and early twenties.20 Thus, when adolescent refugees come to the United States, they may find themselves navigating both a new social and cultural environment as well as new and unforeseen mental conditions. Although statistics on mental illness are difficult to find due to a lack of adequate research and a wide variety of assessment techniques, an estimated 50–90% of adolescent refugees show symptoms of PTSD, while an estimated 6–40% show symptoms of major depression. Rates of mental illness are lower among native-born US citizens, where approximately 9% of adolescents between 12 and 17 have been diagnosed with depression while approximately 5% of adolescents have been diagnosed with PTSD.21, 22 High rates of mental illness among refugee adolescents are further impacted by informal screening techniques and stigmatism of mental illness.

Contributing Factors

Traumatic Experiences

Much of the trauma that children and adolescents face prior to coming to the United States continues to affect them as they adjust to civilian life, putting them at risk of mental illness. Prior to resettlement, refugee children may have experienced traumatic events or hardships, including violence (as victims or perpetrators), lack of food, lack of water, lack of shelter, physical injuries, war, torture, forced labor, sexual assault, loss of loved ones, and disruption or lack of access to education.23 Studies conducted with Syrian adolescent refugees found that direct exposure to violence such as rockets or bombs falling on and damaging neighbors’ homes, as well as harm done to friends and families as a result of war, leads to an increase in psychological problems such as PTSD (see Figure 2).24

Figure 2

Additionally, refugee children and adolescents may be exposed to secondary traumatization through the experiences of their parents.25 In refugee populations where experiences with war and other intense conflicts are common, the parents’ mental health has been linked with the mental health of their children, leading to social, cognitive, and behavioral problems.26 A study done among Bhutanese and Somali refugee parents found similar levels of overall trauma between the two groups, although Somali parents reported higher levels of ongoing trauma post-resettlement. According to the study, 13% of Somali refugee parents self-reported anxiety disorders, while 8% of Bhutanese refugee parents reported anxiety. Also, 16% of Somali and 9% of Bhutanese respondents reported major depression.27

In addition to dealing with the effects of previous traumatic experiences, refugees are often exposed to unhealthy living conditions while living in the camps, which may also contribute to mental health risks. While in camps, refugees may lack access to clean water, electricity, and sometimes even food, which adds further stress to their already stressful experience. Further, fear of sexual assault and disease contributes to the degradation of mental health.28 A study done in a Syrian refugee camp found that adolescents who had arrived in the camp in the past 6 months reported fewer psychological problems than those who had been there for longer than 6 months.29 Although refugee adolescents in this study reported having a strong sense of hope for their future, these adolescent refugees reported a low sense of coherence, which refers to an individual’s ability to cope with stress.30 Stress that accompanies living in refugee camps may exacerbate the existing stress from previous trauma.

Challenges with Acculturation

After coming to the United States, refugees are expected to assimilate quickly into US society, potentially leading to discouragement and mental illness. As adolescent refugees resettle in the United States, they may find the experience difficult due to a number of stressors, including:

- Conflicts between children and parents over new and old cultural views

- Conflicts with peers related to cultural misunderstandings

- Necessity to translate for family members who are not fluent in English

- Lack of education, putting them behind their peers

- Problems trying to fit in at school

- Struggles to form an integrated identity including elements of their new culture and their culture of origin31

Despite large communities in states such as California, where 30% of all refugees came from Iran, or Michigan, which has accepted the highest number of Syrian refugees, most refugees are resettled in areas where there are very few people from their same country.32 Because refugees who lived in camps were previously surrounded by people with similar cultural and traumatic experiences, transitioning refugees to a new culture with a lack of social support may create additional stress.

In a study of 135 Somali refugees under the age of 18 in New England, researchers sought to find the relationship between acculturation and depression. In order to measure the burden of acculturation, the researchers used the Acculturative Hassles Inventory, consisting of 14 items assessing the severity of stress related to an adolescent’s experience, such as “having to translate or explain American culture to family members” and experiencing “parental criticism [for] ‘becoming too American.’”33 Higher severity of stress found from the Acculturation Hassles Inventory was associated with higher rates of both PTSD symptoms and symptoms of depression.34 Previous studies of Eastern European refugees found that higher levels of stress about acculturation among refugee adolescents were only associated with depression when parental acculturation was low.35

A study done with Burmese refugees living in Iowa highlighted a lack of understanding of social cues among adolescent refugees. “In-group members,” known as those who are native to the United States, could be “demanding in terms of maintenance of their own [traditions and culture].”36 Further, problems at home created stress such as “lack of money for food, rent, and bills, children losing moral education, completing homework at home, and communication between children and adults.”37 These problems contributed to higher feelings of isolation and were correlated with symptoms of depression and anxiety. Additionally, the shifting roles of adolescent refugees in their families and new communities may cause confusion and psychological problems.In the study, cultural differences regarding respect for parents in the United States versus Burma created tension between parents and children, which the children “attributed [this tension] to their parents’ lack of desire to change.”38 Cultural adjustments of adolescents may present risks of mental illness due to the burden of understanding their new roles in their communities, families, and schools.

Discrimination and Bullying

The bullying of and discrimination against adolescent refugees by other youth may also lead to increased levels of mental illness. While 1 in 4 children in the US school system reported incidents of bullying, the rates may be higher among refugees due to racial diversity, religious differences, and misunderstanding of social cues.39, 40 A 2015 study done in New York found that among teenage refugees, the most common forms of bullying were race-based bullying, language-based bullying, accent-based bullying, clothing-based bullying, and religion-based bullying.41 This study was done as a focus group in order to assess common types of bullying among refugees instead of understanding the frequency of bullying in refugee communities. Information on the bullying of refugees is difficult to find due to the low concentration of refugees in school districts.

A 2009 study showed that race-based bullying was common among non-white refugees, and those who attended “predominantly white schools were racially targeted by their peers.”42 The concept of race-based bullying is new to many refugee students because of the racial homogeneity of their home countries. Even in schools where white students were not the majority, refugees were still bullied for racial reasons. Participants in the 2015 study reported that the people who bullied them because of their race were typically other students of color. This bullying may occur because victims of racial discrimination are often more likely to engage in racial discrimination against others.43 Perceived discrimination was the strongest predictor of depression in a study done on the mental health of recently resettled Somalian teens.44 Among these teens, perceived discrimination was also indicative of negative self-image, which has been shown to lead to further depression.

Religious discrimination may disproportionately affect refugee adolescents due to the high number of refugees from countries with predominantly Muslim populations. Syrian, Iranian, and Burmese refugees who identify as Muslim are often discriminated against due to negative perceptions of Islam in the United States. Among conservatives in the United States, 63% said they believed Islam encouraged violence.45 For high school-aged girls, this discrimination may be more common due to the visible nature of their distinctive religious hijab.46 Religious differences can cause teens to stand apart from their peers, creating additional stress and feelings of isolation. Additionally, religious discrimination often leads to rejection from peers, which is correlated with a higher likelihood of depression and dropping out of school.47

Separation from Parents

Currently, there are approximately 1,300 unaccompanied refugee minors (URMs) across various US states, which creates concern regarding mental wellbeing, as separation from parents is a factor in mental illness.48 Although some URMs may be reunited with their parents at a later time, many initially come to the United States without parents or even familial connections. Unaccompanied minors face a variety of risks prior to resettlement, as mentioned in the traumatic experiences section, often putting them at a higher risk of experiencing PTSD.49 During times of war, the effect of separation from a parent can create higher levels of anxiety in children and youth.50 Additionally, some refugees who come to the United States may be separated from siblings in the process of migration, which further contributes to feelings of isolation.

Studies have shown that parental support is crucial to children during traumatic experiences and have “identified separation from family members as an important threat to the mental health of refugee children and adolescents.”51 A number of reasons have been determined pertaining to the higher likelihood of psychological distress among URMs: “the lack of social support necessary to cope with the stresses inherent in migration, the deprivation of emotional relationships and the loss of familiar environment, their increased exposure to traumas before or during the flight, and their relative lack of social and economic resources.”52 The lack of parental support during the transitional stage of resettlement may lead to depression.

Awareness of Mental Illness

Despite increasing understanding of mental illness in the United States, mental health awareness varies in different cultural contexts, making it less likely for struggling refugees to receive help. In many countries where refugee crises occur, mental health services are associated with patients with severe mental health concerns, often classified as psychotic. Due to the perception of mental health services and those who use them, mental illness is often stigmatized.53 Some refugees from regions of the world with negative perceptions of mental illness may be dissuaded from seeking medical attention or even acknowledging the existence of mental illness as a health concern.

Understandings of mental illness vary among refugees due to cultural differences, making it difficult to assess mental illness. For example, some groups from Southeast Asia “perceive that supernatural forces/phenomena are responsible for mental health issues” associated with “denial of spirit or deities.”54 Further, some individuals in African countries, including Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Kenya, believe that “supernatural agents can possess a person and might cause physical or psychological disorders.”55 The idea of spirits making demands leads individuals to believe that to be free of the influence of the spirit, they must fulfill such demands in order to be free of the influence of the spirit. Mental illness is often stigmatized in Arab communities, where religious-psychological healing is preferred. Individuals with mental illness “may not seek advice from professionals or even family members. Most Christian and Muslim Arabs hold strong religious principles that play a substantial role.”56 Additionally, Arab culture typically maintains that individual behavior is a reflection of the family, which puts pressure on individuals to maintain dignity. The perceptions of mental illness significantly impact one’s willingness to seek out mental health services, allowing mental illness to have lasting effects on refugees.

Misconceptions about mental health may cause problems in attempting to diagnose mental illness in refugees. Due to different understandings of mental illness among refugees, they may explain symptoms in ways that are unfamiliar to health professionals, which, in turn, may make diagnosis difficult. For example, in Syria and Myanmar, mental illnesses may be spoken about in terms of spirituality or physical illness.57, 58, 59 When the mental health of refugees are assessed in camps, mental health assessments is often done by interviewers with little to no training. Special protection and consideration for traumatized individuals may be overlooked due to inadequate methods used by interviewers.60 The combination of informal practices, as well as a lack of understanding of cultural terms and practices, further contributes to the unaddressed mental health needs of adolescent refugees.

Consequences

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

PTSD is common in the refugee population, where the rates are estimated to be almost twice as high as the general population.61 As of 2019, approximately 3.5% of adults in the United States suffer from PTSD, while rates among those under the age of 18 are slightly higher at 4%.62, 63 Although estimates vary depending on the measurement techniques used, between 10–15% of refugees show symptoms of PTSD. A 2011 review of over 20 studies of refugee mental health found that PTSD occurred at even higher rates among children and adolescents, with studies finding that 19–54% of adolescents showed symptoms.64 Additionally, a study conducted in 2016 of refugee camps in Germany found that 33% of Syrian refugees between the ages of 7 and 18 displayed symptoms of PTSD.65

In adolescents, PTSD can cause a variety of behaviors: anxiety, depression, extreme aggression, behavioral problems, inability to form bonds with others, sexual promiscuity, substance abuse, self-harm, suicidal thoughts, and borderline personality disorder.66 Teens are more likely to exhibit impulsive and aggressive behaviors, and additional stress from migration may make these behaviors especially pronounced in refugee teens.67 Although other common consequences of migration, such as anxiety and depression, affect migrants of all backgrounds and ages, adolescent refugees, specifically those who are unaccompanied, are at a higher risk of developing PTSD.68 Consistent stress associated with PTSD has physical costs in addition to the mental costs. Effects of continual stress on the brain and nervous system result in “wear and tear” on the body. Physical ailments associated with PTSD include heart disease, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, and irritable bowel syndrome.69

Anxiety

Anxiety disorders are the most common mental illnesses in the United States, with 18.1% of individuals over 18 reporting symptoms of anxiety at any given time.70 Adolescent refugees typically have higher rates of anxiety, although rates vary depending on country of origin. A self-completed survey found that 19% of Bhutanese refugees in Australia showed symptoms of anxiety, while a study of Iraqi refugees in Jordan found that 60.8% displayed high levels of anxiety.71, 72

Syrian refugee children who resettle in the United States reportedly face higher rates of anxiety in comparison to children born in the United States. Recent studies done in Michigan found that 61% of Syrian children had probable anxiety diagnoses while 85% had probable separation anxiety diagnosis. Additionally, higher PTSD symptoms among mothers were associated with higher anxiety levels among children.73 Overall, Syrian children had higher diagnoses of anxiety in comparison to refugees who were not from Syria. A number of physical symptoms are associated with generalized anxiety disorder, including74:

- Feeling restlessness

- Feeling on edge

- Being easily fatigued

- Having difficulty concentrating

- Feeling irritable

- Experiencing muscle tension

- Experiencing sleep disturbance

Those who suffer from panic disorders may have difficulty breathing, chest pain, dizziness, numbness in arms and legs, gastrointestinal issues, sweating, and trembling.75 Anxiety may also have long-term effects on health. Women with high levels of anxiety were 59% more likely to have a heart attack, and gastrointestinal issues often increase a person's vulnerability to developing Crohn's disease (ongoing inflammation of the membrane lining the colon). Anxiety has also been linked with chronic respiratory disorders such as asthma.76

Depression

In addition to PTSD and anxiety, refugees suffer from depression at a higher rate than the general population. An estimated 5–15% of refugees in the United States suffer from depression, compared to approximately 6.5% of the general population.77, 78 Large differences in mental health diagnoses may occur between refugees due to differing experiences and a wide variety of measurement techniques used by surveyors. Additionally, research focused on the mental health of adolescent refugees in the United States is minimal. In consequence, analyzing studies from a variety of countries where refugees reside are needed to better examine the effects. A study done on Syrian refugees in German refugee camps found that 88.2% of those referred to mental health services had some form of depression, making it the most common mental illness.79 More specifically, one study done of Yazidi youth who resettled in Turkey found that 32.7% of adolescents aged 7–17 had symptoms of depression.80 Of adolescent refugees in Uganda, 31–42.5% showed high levels of depression, and rates were higher among those whose caregivers showed symptoms of depression.81

Depression is linked to serious social and educational challenges, as well as an increased rate of smoking, substance misuse, and obesity.82 Further, mental illnesses, specifically depression, are often cited as the cause of suicide or suicidal thoughts. A study done in 2001 reported that bullying targeting Haitian and Hmong refugee students on the basis of race often caused suicidal thoughts and decreased self-value.83 Recent suicide rates in the Bhutanese refugee community are nearly 3 times higher than the general population.84 Suicide rates among teens in refugee camps occur at higher rates than those outside refugee camps. In a study conducted in a refugee camp in Lesbos, Greece, researchers found that between February and June of 2018, nearly a quarter of the children (18 out of 74) aged between 6 and 18 years had self-harmed, attempted suicide, or had thought about attempting suicide.85 In the United States, adolescent refugees may be more likely to attempt suicide due to higher rates of depression.

Substance Abuse

Research about the prevalence of substance abuse and its effect on mental illness in US refugee communities is limited, but there is evidence that it may be a problem. A study of refugee children and adolescents receiving treatment through the National Child Traumatic Stress Network found that less than 4% had a substance use disorder.86 However, mental illness is often correlated with problems of substance abuse, as individuals try to self-medicate.

Although many studies measure substance abuse in relation to alcohol consumption, it is important to note that some countries have other preferences for mood-altering substances or drugs. In Southeast Asian communities, chewing areca nut (also known as betel nut) is common, as it is believed to be an aphrodisiac and a source of energy.87 With an influx of refugees from Southeast Asia, betel nut is becoming more common in the United States. Betel nut contains ingredients known to boost mood and increase energy.88 However, betel nut is not harmless. Betel nut has been associated with oral cancer, peptic ulceration, and abnormal liver functions.89 Further, betel nut is available at a variety of East Asian grocery stores around the United States, unregulated by the FDA.90 Despite low rates of substance abuse, more research is necessary to understand how mood stimulants native to refugees’ homeland affect mental health.

Social Consequences

Mental illness often impairs the social capabilities of individuals. For refugees who have recently resettled, the consequences of mental illness may affect their success in adjusting to their new community. Trauma affects the performance of refugees in school as well as their ability to adapt to a new culture. Effects of PTSD also lead to reduced interest in school and anxiety in new circumstances, negatively impacting the adjustment phase.91

A study in 2017 shows that higher rates of anxiety among Syrian children negatively affect their chances of succeeding in school.92 Anxiety in teens causes a variety of physical and mental challenges, which often leads to performance problems in school, sports, and social interactions.93 Adolescent refugees may struggle to adjust to their new surroundings in US culture, where competence and value are sometimes measured by success in these 3 areas.

A study of depression in teens revealed that those with severe depression were less likely to succeed in school. While 76% of teens with low levels of depression obtained a GPA of 2.0 or better, only 68% of teens with mid-range levels of depression had a 2.0 or better, and only 57% of teens with the most severe level of depression had a 2.0 or better.94 Depression also affects youth in other ways, including a withdrawal from friends and family, an inability to concentrate, and irritability.95 Additionally, those who are depressed as youth have a higher probability of unemployment, higher rates of divorce, and lower rates of income in the future.96

Besides the effect on educational attainment, mental illness may affect the social abilities of adolescent refugees. Studies done on Yazidi refugees in Iraq found that some adolescents might have had increased stress due to the pressure to take care of younger siblings, making it hard to participate in social gatherings with other youth.97 Children who had been exposed to violence in refugee camps struggled with social situations, appearing very shy and avoiding contact with other children in the camp.98 It is also important to note that teenage girls are more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with a mood disorder as boys, about 14–20%.99 Due to the prevalence of mental illness in teens and the unique experiences of refugees, these combined circumstances may impact their ability to socially assimilate.

Practices

Intervention in Schools and Community

Due to the challenges adolescent refugees face assimilating to their new culture, many mental health practices for refugee youth focus on creating support in schools and communities. The underlying goal of these organizations is to create safe spaces for adolescent refugees where they can grow in their understanding of both educational pursuits and mental health concerns. Because schools can be a source of a considerable amount of stress for adolescent refugees, many programs focus on intervention in schools, while others incorporate community support into their strategies.

One example of school intervention is Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS). CBITS was first implemented in urban areas to alleviate the effect of violence on children. The program consists of 10 group sessions, 1–3 individual sessions, 2 parent psychoeducational sessions, and 1 teacher education session.100 Due to unfamiliarity with mental health services among refugees, engagement is critical.101 Engagement strategies include offering practical assistance to the families and making sure they are linked to other services including general health care. Including families and important members of the cultural community in the process is also important in reducing stigmas surrounding mental health.102 So far, it has been implemented in 13 states and the District of Columbia. Cognitive-behavioral therapy uses several techniques such as psychoeducation, relaxation, social problem-solving, and cognitive restructuring.103

Boston Children’s Hospital’s Refugee Trauma and Resilience Center created its own variation of community based therapy, Trauma Systems Therapy for Refugees (TST-R), with the intent to create a holistic approach supporting refugee youth.104 The goals of this program are: to build a support system for the adolescent; to intervene through direct interaction with the teen, their family, and their peer groups; to reduce distrust of authorities by connecting with the community; to reduce the stigma of mental health services by combining services with existing and familiar services; to reduce cultural barriers by creating partnerships between providers and cultural experts; and to reduce resettlement stressors by integrating services.105 Currently, TST-R practices are being utilized in several initiatives across the United States, including cities in Maine, Massachusetts, and Kentucky.

Another strategy that focuses on community support is the Trauma Sensitive Schools (TSS) approach. TSS attempts to address individual trauma holistically, focusing on school-wide engagement in promoting a safe environment for students to process traumatic events.106 TSS provides resources for educators to practice trauma-sensitive techniques while also providing a platform where ideas can be exchanged between educators.

Impact

Although there is limited to no research on intervention in schools for refugee populations, there is evidence that it is an effective solution for some similar populations. According to a study by the CDC, there were “significant improvements in symptoms of PTSD and depression” in school settings in the case of CBTIS, especially for urban minority groups living in poverty with limited access to health care.107 A 2003 study of CBTIS involved 200 Spanish-speaking immigrant students in Los Angeles who had been exposed to violence or had similar mental health diagnoses (PTSD or depression). Using those who were referred to mental health services as a baseline, a 17% decrease in depressive symptoms was found in the students while the control group did not see any significant decrease. Those with PTSD symptoms found a decrease of 29%.108

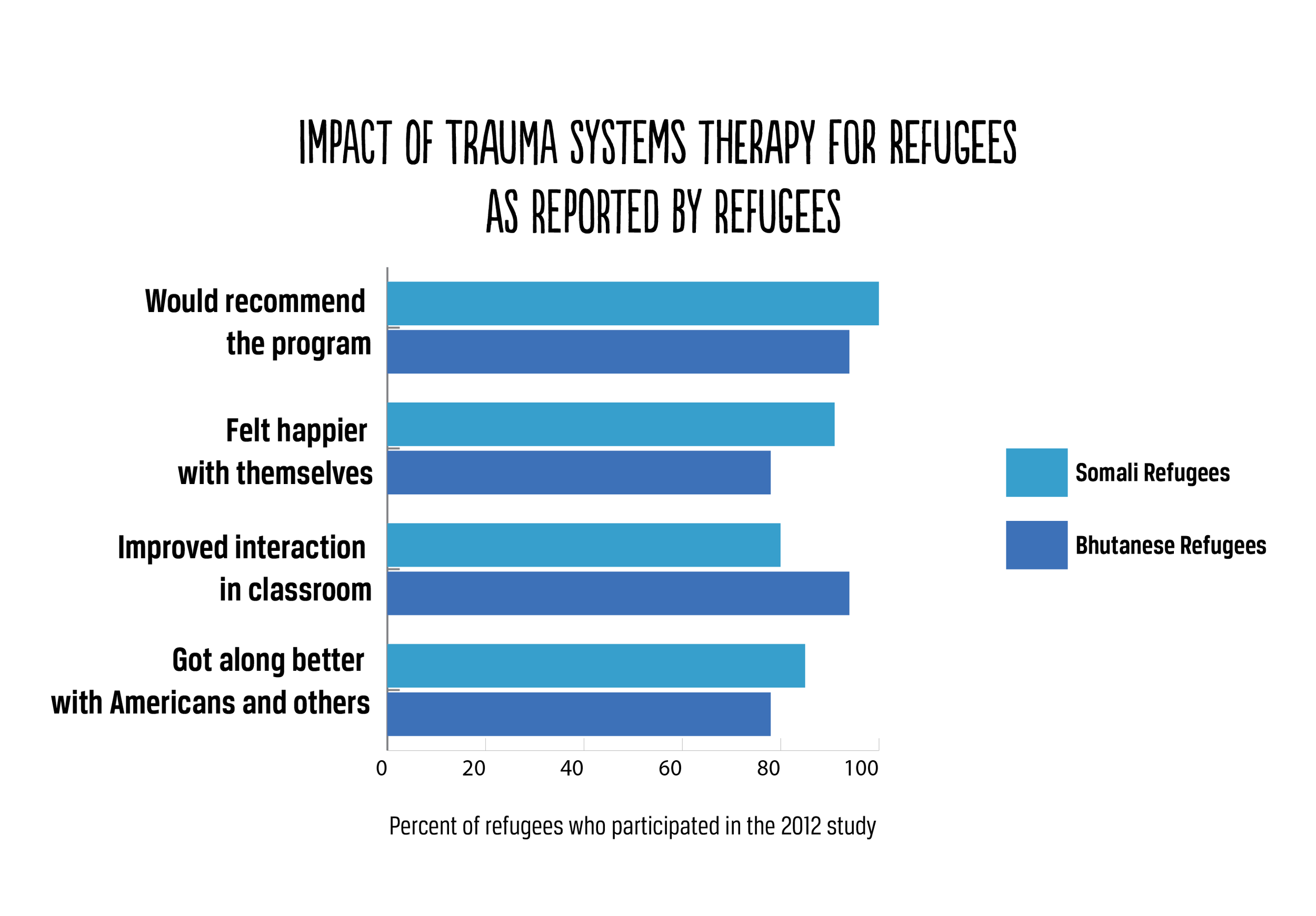

Additionally, a qualitative evaluation of TST-R from a 2012 study of the Somalian and Bhutanese refugee communities showed overall success (see Figure 3).109

Figure 3

Gaps

Despite the successes of CBITS with children in low-income areas, there has been no conclusive evidence of the work done with refugees. Furthermore, the model in schools is not specifically for refugees, which means there may be some disconnect between refugees and their peers. Studies done on CBITS focus on homogenous racial groups, such as majority Latino areas in Los Angeles and American Indian reservations in Montana and New Mexico.110 Thus, the results may be different in areas where refugees are not the majority and school administration does not see the need for such programs. Additionally, this practice does not account for cultural differences that may exist between those of differing refugee backgrounds.

Although qualitative results of TST-R show promising results, the surveys observed did not include evaluation from a psychologist after the process, instead relying on self-reporting from the refugees themselves. Additionally, the phase-based intervention lasts a long time (often a year) and requires an interdisciplinary team assembled through various funding sources. The high level of community engagement required may present problems for individuals who live in communities without high levels of engagement. Additionally, some components are not reimbursable through insurance, which may prevent implementation.111

Individual Therapy

Therapy for adolescent refugees is important to the recovery process. A variety of therapy practices are currently utilized to address mental health concerns among refugees. Although the availability of therapeutic techniques varies from state to state, two main practices have been associated with treating mental illness among adolescent refugees. These methods are Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) and Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET). These therapeutic techniques have been implemented in refugee camps internationally as well as in private clinics within the United States.

EMDR has been suggested for survivors of trauma and torture since its initial creation in 1991 but has only recently found its way into the refugee community.112 The purpose of EMDR is to help individuals confront traumatizing experiences from their past. Like other forms of therapy, EMDR requires individuals to relive the experience through memory. Unlike other forms of therapy, EMDR focuses on the movement of the eyes, in which the purpose is to shift the “stuck memory” into a new experience.113, 114 Refugee-specific modifications to EMDR include accommodation techniques such as sessions held in the native tongue of refugees and treatments administered by those familiar with the customs of the people.115 Cultural awareness is key in the practice of EMDR, especially for those who have never been introduced to therapy previously.

In contrast to EMDR, NET focuses on the traumatic experiences of refugees in-depth, encouraging them to construct a narrative of their life up to the present and elaborate on specific experiences.116 Whereas other forms of therapy focus on single traumatic events, NET addresses the traumatic event in the timeline of the individual’s entire life, requiring patients to become accustomed to the emotional responses associated with traumatic events.117 Adaptations have been made in which refugees are treated by other refugees trained as counselors in order to lessen the impact of cultural barriers. Variations of NET have been adapted to meet the needs of youth (ages 7-16) in the form of KIDNET. In this variation, therapists may use visual aids such as rope, string, rocks, and flowers in order to help children reconstruct traumatic events.118, 119

Impact

In a study of 30 Syrian refugees in Turkey aged 16-34, a control group of individuals who were “waitlisted” was compared to a group that received EMDR treatment. The study found that those who received treatment had significantly lower rates of PTSD symptoms in comparison to the control group.120 Despite lower rates of PTSD symptoms, they did not find any difference in symptoms of depression in the control group and treatment group.

A 2010 study of the effectiveness of KIDNET assessed 26 refugee youth who participated in 6 sessions of the treatment. After 9 months, the KIDNET group had a clinically significant decrease in PTSD symptoms. At a 6-month follow-up, 70% of participants in the control group showed signs of PTSD, compared to 17% in the KIDNET group.121

Gaps

Despite the positive results of the two studies, these study groups are relatively small samples that do not yield overall conclusive results. There would need to be more tests done in bigger areas, especially in the United States. Additionally, existing research focuses mainly on Syrian refugees due to the higher prevalence of PTSD in these communities, calling into question whether or not studies would yield similar results when done with refugees from different regions of the world. Also, the study using EMDR treatment proved to be ineffective in treating symptoms of depression, which is found more often among adolescents. EMDR has also been modified specifically for refugees currently residing in camps or recently brought from camps.122 Thus, research focuses on the effects of EMDR in refugee camps and not resettlement in the United States. Additionally, because EMDR is mainly practiced in private clinics in the United States, data is not readily available. Similar caveats exist in studies done on NET treatments, focusing mainly on those in refugee camps and not treatments done in the United States.

Mental Health Education for Refugees and Providers

Instead of educating refugees directly about mental health, some programs seek to provide resources to those who already provide general mental health care in order to help them adapt to refugee needs. One of the concerns with treating mental illness in younger refugees is knowing how to bridge the gap between US culture and the culture of their homelands. An increase in understanding of cultural differences among refugees by health care providers can improve the quality and effect of the mental health care the refugees receive.

Several organizations and agencies provide information about the mental health of refugee youth, including the Refugee Health Technical Assistance Center (RHTAC), the Refugee Trauma and Resilience Center, and the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN). The RHTAC provides an overview of mental health in adolescent refugees, which includes several webinars meant to train professionals on implementation strategies. These webinars include topics such as risks and concerns of refugee youth adjustment and suicide among refugees.123 One of the services recommended by RHTAC is the Refugee Services Core Stressor Assessment Tool,124which is used in order to identify stressors related to relocation and past experiences.125

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network provides information about the mental health considerations of refugee adolescents. This information includes how providers can best with refugees in a medical setting, how trauma might prevent itself in a primary care setting and in families, and how providers can work within an existing service system to support refugee patients. Suggested provider considerations include using interpreters and understanding language barriers, respecting the roles of caregivers in adolescents’ lives (for example, parents not using children as interpreters), and not assuming any information. Additionally, NCTSN mentions how mental illness may be manifested in terms of physical symptoms (such as stomachaches) and how it may be necessary to explain mental health to parents in terms of stress and readjustment.126

Impact

Research on the effectiveness of educating mental health care providers is minimal. There are currently no reported impact analyses of resources for mental health care providers. However, several studies have been conducted on the effectiveness of mental health education overall. A review of mental health education in 2012 examined over 26 studies regarding changing attitudes about mental health corresponding to theoretical education.127 The methods included showing videos to healthcare students and providing lectures and presentations by people with mental illness in order to educate students about the issue. Overall, the review showed that mental health-related education was effective in changing the attitudes of healthcare providers toward mental illness.

Gaps

Although there are studies concerning mental health education generally, there are no current studies regarding educating refugees about mental health concerns. In general, there is a lack of data on the dissemination of information to mental health care providers and how it impacts mental health. Thus, it is difficult to discern if the quality of health care provided to refugees has increased as a result of providers’ access to resources.

Preferred Citation: Lloyd, Kate. “Mental Illness Among Adolescent Refugees in the United States.” Ballard Brief. February 2019. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints