Perpetuation of Poverty in Rural Tanzania

By Dan Raleigh and Madison Coleman

Published Winter 2020

Special thanks to Madison Coleman for editing and research contributions

+ Summary

The majority of Tanzania’s population lives in rural areas and experiences extreme poverty. The rural population experiences greater poverty and faces more barriers to escaping the cycle of poverty than urban populations. Several factors influence rural Tanzanians’ inability to mobilize and obtain the necessary resources to escape poverty, including the practice of subsistence farming, limited infrastructure, and poor access to education. The consequences of poverty for the rural population include inadequate healthcare services, heightened disadvantages for women, poor nutrition, and increased child labor. Several organizations in Tanzania and nearby countries are working to halt the perpetuation of poverty and mitigate the effects of poverty in rural areas by promoting sustainable agricultural practices, investing in livestock development, and providing health resources.

+ Key Takeaways

+ Key Terms

Subsistence farming -“Farming that provides enough food for the farmer and their family to live on, but not enough for them to sell.”1

Agricultural inputs - Substances used by a farmer for pest control or for soil fertility management. Examples may include compost, mineral calcium, or animal by-products such as fishmeal.2

Value chain - “A business model that describes the full range of activities needed to create a product or service. For companies that produce goods, a value chain comprises the steps that involve bringing a product from conception to distribution, and everything in between—such as procuring raw materials, manufacturing functions, and marketing activities.”3

Food price shocks - An unexpected or unpredictable event that affects an economy. The extent of a price shock can be limited to local, regional, national, or global economies or markets. In low-income countries, a price shock affecting crops to which a region depends can add financial strain on the population and can result in nutrient-deficient diets.4

Food insecurity - “A decrease in food intake or disruption of eating patterns because of lack of money and other resources.”5

Agropastoral - “A way of life or a form of social organization based on the growing of crops and the raising of livestock as the primary means of economic activity.”6

Rotating credit club - A group of individuals that pools money in a common fund to allow members to save and borrow together. These types of groups are most common in developing economies.7

Cooperative - “A private business organization that is owned and controlled by the people who use its products, supplies or services.”8

Child labor - Any work that is physically, mentally, morally, or socially harmful for children or that interferes with their ability to attend school.9

Agroecology - “An ecological approach to agriculture that views agricultural areas as ecosystems and is concerned with the ecological impact of agricultural practices.”10

Context

Tanzania is the second most populated East African country,11 with a total population of over 58 million as of 2019—approximately double what it was in 1994 at 28.7 million.12 As is typical of sub-Saharan countries, around 65% of Tanzania’s population lived in rural areas in 2019;13 in comparison, the neighboring countries of Kenya and Zambia have around 73%14 and 56%15 of their populations, respectively, living in rural areas. Rurality is a definitive and influential factor for the lives of many in Tanzania. Due to a low population density and various geographic constraints, the country’s rural population relies largely on agriculture as its primary source of employment and food.16 Tanzania’s economy also relies heavily on the agriculture industry, which employs 65% of the nation’s workforce.17

Tanzania’s economic conditions are defined by the country’s major industries as well as the government’s involvement in distributing economic resources. In 2019, Tanzania’s GDP was US $63.18 billion, representing only 0.05% of the world's economy.18 Its GDP per capita as of 2019 was US $1,122,19 compared to Kenya’s and Zambia’s per capita GDPs of US $1,81620 and US $1,291,21 respectively. These are considerably low compared to many western nations, such as the United States’ GDP of $55,809.22 In addition to agriculture, which accounts for nearly 25% of Tanzania’s GDP,23 the other principal contributor to Tanzania's economy is the tourism market, which made up 17.5% of its GDP in 2016.24 Additionally, because of the government corruption occurring at the local, state, and national level, resources are poorly distributed and economic inequality is perpetuated between those in rural areas and in urban areas.25 26

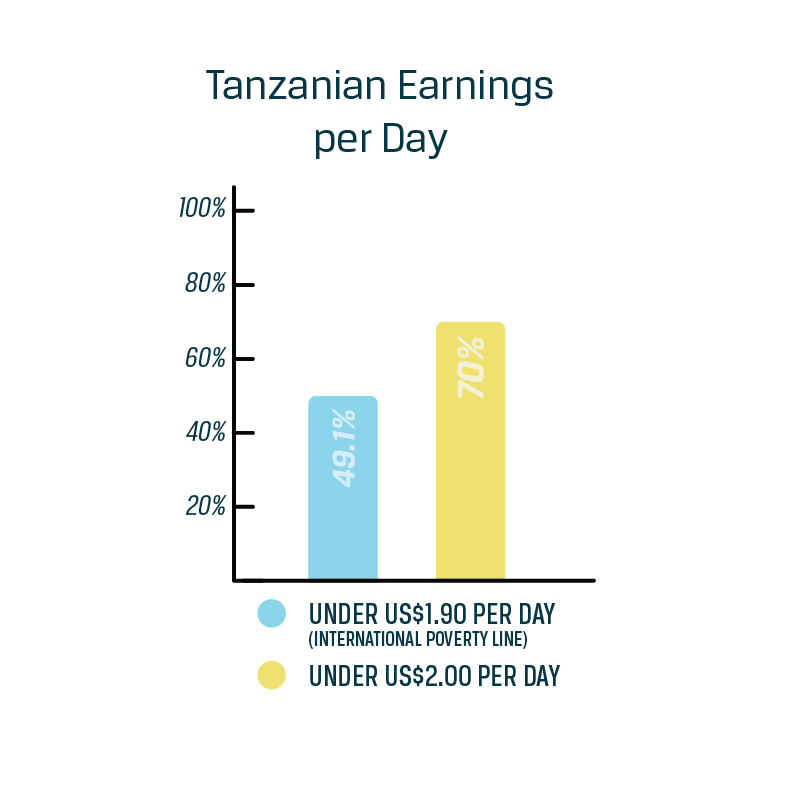

Poverty is a complex topic and is nearly impossible to measure, especially in Tanzania; however, organizations such as the World Bank use standardized monetary measures in order to quantify poverty worldwide. The international poverty line established by The World Bank is set at earning US $1.90 (or about 1,783 Tanzania shillings27) per day.28 Those living under this amount are considered to be in extreme poverty.29 Under this definition, Tanzania has a poverty rate of 49.1%,30 and approximately 70% of Tanzanians live below $2.00 per day.31 However, poverty can be measured through many other factors, such as access to quality resources—including sanitation and utilities—and ability to economically mobilize. About 57.6% of rural Tanzanians are impoverished according to the multidimensional poverty measure, which accounts for access to basic resources.32 In this brief, poverty will be analyzed through this definition, in addition to monetary measures.

When poverty is analyzed through the lens of access to basic resources and necessities, it is clear that most individuals in rural Tanzania experience extreme poverty. Among the 66% of the population that live in rural areas, only 8.3% have access to a standard sanitation facility (defined as flush or pour-flush toilets that are piped to a sewer system, septic tank, or latrine).33 Out of the general population, 29.2% have no access to standard drinking water and 44.3% have no access to electricity.34 Tanzania is seeing a steady reduction in overall poverty, but has experienced slow economic growth among its poorest populations in the last decade.35 As the population continues to grow, poverty has reduced in rural areas but remained fairly stagnant in urban areas.36 Still, a significantly larger number of rural inhabitants are living in poverty than urban inhabitants. Under the measures for national poverty, 33.1% of the rural population lived in poverty as of 2018, as compared to 15.8% in urban areas.37

Because poverty is so prevalent for those in rural Tanzania and has been perpetuated among this population for generations, the factors that prolong the cycle of poverty are currently more relevant than those that placed rural Tanzanians in poverty in the first place. As such, this brief focuses on understanding the causes and consequences that are sustaining the poverty cycle and the practices that help individuals mobilize and break out of that cycle.

Contributing Factors

Subsistence Farming

Much of the rural population relies on subsistence farming, a practice that can perpetuate poverty due to its unpredictable nature and inability to help citizens mobilize beyond their rural communities. More than 80% of Tanzanians rely on agriculture for their livelihoods, and 95% of land under production is cultivated by subsistence farmers.38 Subsistence farming, or smallholder agriculture, refers to when a family grows and harvests only enough food to feed themselves and stores the remaining food until the next harvest.39 This method allows food to be produced at minimal costs and eliminates the need to find transportation to a city to sell the crops for profit. Families are able to live independently and self-sufficiently without needing to purchase or borrow household items and food from other sources. Often, families choose to invest whatever capital remains back into livestock and agriculture. Those who practice subsistence farming have no other source of income because they must allocate their time to tending to their farms and animals rather than working for income.40

A subsistence lifestyle allows for self-reliance when farming conditions are ideal. However, conditions for the farming season in Tanzania are rarely consistent. Regional weather and climate-related issues, such as extended seasonal droughts and flooding, play an important role in determining whether adequate levels of food will be produced. Disease, inadequate agricultural inputs, and rudimentary technology can also affect harvest scarcity.41 This dependence on uncontrollable circumstances leaves many rural farmers helpless to the weather trends and volatile climate. When these weather trends occur, households generally cannot produce enough food to meet their nutritional needs. Households often experience food shortages that last, on average, at least three months per year.42

Subsistence farming perpetuates a closed-loop poverty cycle because it not only prevents rural Tanzanian families from generating enough food to feed themselves year-round but also from earning enough money to pull themselves out of poverty. Even if families produce high agricultural yields, these yields do not provide sufficient profitable outcomes to promote economic viability.43 There is little empirical evidence that identifies a clear link between agricultural productivity and economic welfare among rural African communities.44 This implies that, as long as rural Tanzanians continue to allocate the majority of their time and resources to subsistence farming, they will not be able to generate enough income to escape the cycle of poverty. Moreover, farmers that want to transition into commercial agriculture in order to earn additional income experience significant barriers. Most of the plot sizes in rural Tanzania range from 0.9 to 3 hectares, which is too small to transition into commercial agriculture.45 This means that even if farmers have more fertilizer, seeds, and water available for production expansion, significant changes in the agricultural sector in order to enlarge plot sizes would be necessary for subsistence farmers to increase their income.46 Although success in subsistence farming can help those in poverty, it fails to solve the extreme poverty experienced in rural regions because no additional crops or other agricultural products are left over to sell in order to generate necessary income.

Limited Infrastructure

Economic Infrastructure

One of the largest contributing factors to poverty in rural Tanzania is the absence of economic infrastructure. Economic infrastructure includes the basic services necessary for the economy of a nation, region, or city, such as transportation, energy, water, and financial markets.47 Because so many people living in rural areas practice subsistence agriculture and thus are unable to save money due to limited income, these populations need access to adequate economic infrastructure and profitable investment opportunities so that they can economically mobilize.48 Rural Tanzania, however, lacks an economic infrastructure due in large part to the physical remoteness of rural regions from city centers as well as geographical constraints that limit transportation to and from rural areas to urban areas. Some rural areas are closer in proximity to urban areas yet have geographical barriers such as major terrain or elevation challenges; without motor vehicle transportation, this impedes rural citizens’ access to city centers and adequate infrastructure.49 Additionally, the Tanzanian government has invested very little in creating and improving public transportation from rural to urban areas. For example, the Tanzania-Zambia Railways (Tazara) has been in operation for almost four decades but still experiences frequent derailments and breakdowns, and only 2% of the rail line’s cargo capacity is being used.50 Distance and geographical barriers from urban centers, coupled with the inadequate transportation infrastructure, limit people’s ability to engage in market systems, which perpetuates monetary poverty and halts the ability to progress.51

Social Infrastructure

The absence of community infrastructure in rural Tanzania limits access to political and labor market representation, hindering the population and keeping individuals living in poverty.52 Individuals living in rural areas participate in many community groups (such as rotating credit clubs and cooperatives); however, these networks are weaker than those in urban areas.53 Rural groups are “oriented toward helping their members survive, rather than connecting them with other similar groups and actively seeking to forward their particular interests in political arenas or the marketplace.”54 Social groups that help their members to network with others and access political representation have the potential to help individuals increase their earning potential and enter higher-paying labor markets.55 Because rural communities lack these types of groups, individuals in the rural population are less able to tap into resources that would enable them to escape poverty.

Poor Access to Education

Due to the cyclical nature of poverty, many consequences of poverty are also contributing factors because they act as barriers to keep impoverished individuals from mobilizing out of poverty. Therefore, although impoverished individuals living in rural Tanzania are less likely to access quality education, less education also keeps people within the cycle of poverty.

Children in rural areas face more barriers in their ability to regularly attend school and to access a higher quality of education than those in urban areas, perpetuating long-standing gaps between rural and urban educational attainment as well as rural and urban poverty. These barriers in rural areas include higher teacher shortages and dangerous or long journeys to school.56 As of 2010, 88% of urban Tanzanian children and only 79% of rural children attended primary school.57 This disparity in education rates is exacerbated in secondary schools because few rural communities have the resources to operate secondary schools. This means many rural children have to travel long distances—on roads that are sometimes seasonally impassable—in order to continue their education past the primary level.58 Thus, 45% of children in urban areas attend secondary school in Tanzania, compared to only 19% of children in rural areas.59 Because rural children are receiving less primary and secondary education than their urban counterparts, they are less able to access higher-paying jobs that would allow them to escape the cycle of poverty and are instead forced to remain in subsistence agricultural professions.

Consequences

Because so many in the rural population live in poverty, poverty and rurality in Tanzania are deeply intertwined; thus, researchers can experience difficulty determining whether the negative outcomes experienced by the rural population are due to poverty or to the location and isolated nature of their communities. Therefore, many of the consequences that will be discussed are influenced by the poverty experienced by rural populations but are also largely caused by the rural setting of the communities themselves.

Inadequate Healthcare Services

Impoverished areas have limited access to quality materials and supplies, something that both hinders the standard of healthcare being delivered and dissuades many healthcare workers from wanting to practice in these areas. The healthcare system of Tanzania consists of small community clinics in the most isolated rural areas as well as larger hospitals at the district and regional levels.60 The rural clinics often experience a shortage of equipment and medications because the poor rural families they serve are not prioritized by government funding.61 Researchers found that the probability of having the equipment necessary to perform medicinal injections in rural Tanzanian clinics was around 40%.62 Furthermore, World Bank reports reveal that only about 36% of rural healthcare clinics had access to clean water, electricity, and improved toileting, while 79% of urban clinics had access to these resources.63 Medicines are also in short supply in these rural clinics; only approximately 60% of drugs that were deemed essential for healthcare facilities were found in Tanzanian clinics.64

In addition to an expansive physical resource shortage, rural Tanzanian clinics also experience shortages in qualified healthcare providers. Tanzania as a whole has been facing a severe human resource shortage for healthcare workers—a problem amplified in the rural areas of the country.65 According to the World Bank, even though 70% of the Tanzanian population and 85% of the poor live in rural areas, only 28% of the country’s health workforce and 9% of its doctors served rural areas in 2016.66 This is due in part to many doctors and nurses not being willing to remain stationed in remote or removed clinics because of the lower-quality working conditions found in many rural, impoverished areas.67 Though many private and public facilities in rural areas offer incentives to encourage healthcare providers to serve in rural areas,68 healthcare providers stationed in these areas still report feeling overworked and underpaid.69

Within rural clinics, there are varying complications that result from lack of medical expertise of the doctors in conjunction with outdated or neglected equipment and low or no supply of prescriptions and other medical supplies.70 When doctors have limited expertise and outdated or neglected equipment, diagnoses are often inaccurate, causing medical professionals in urban areas to significantly outperform their rural counterparts. For example, only 50% of rural doctors (versus 66% of urban doctors) correctly diagnose five common conditions among Tanzanians: malaria, diarrhea, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and diabetes. In public health clinics, rural providers correctly diagnosed only 44% of all health issues.71 In the case of infant deliveries in rural areas, only 55% are assisted by skilled health professionals, as compared to 87% in urban areas.72 Because rural communities are more impoverished and removed from urban areas, rural residents receive a reduced quality and quantity of healthcare services.

Gender Disadvantages

Gender inequality is prevalent across much of sub-Saharan Africa because of cultural traditions and beliefs, and the opportunities afforded to women only decrease as a result of poverty.73 According to the chair of the UN Economic Commission for Africa’s Committee on Women and Development, this is because poverty reduction strategies do not take into account gender differences in income and power, thereby designing finance programs that are more likely to benefit men than women.74 Since Tanzanian women are more likely than men to experience limited access to education, health services, and economic opportunities,75 the exclusion of women from poverty reduction programs further enhances how poverty puts women at an even greater disadvantage than men.76 Forms of gender inequality also exist in political participation and decision-making, division of labor, and resource access and control.77 The combination of these factors leads to Tanzania being ranked 129 out of 188 countries on the Gender Inequality Index (GII).78

These inequalities are enhanced among rural populations. Rural women experience much greater levels of time poverty than their urban counterparts. Poor women in rural areas face time constraints due to particularly high burdens associated with large families, household tasks, and farm responsibilities.79 The rural poor spend more time cooking because they are using simpler tools, more time cleaning because they are cleaning by hand, more time traveling because they must walk long distances, and more time farming because they possess either few or no farm tools or machinery.80 Women also experience much greater levels of time poverty than their male counterparts. On average, Tanzanian women spend 13.6% of their time per day on unpaid work compared to men spending 3.6% of their time on unpaid work.81 This results in rural women being at a greater economic disadvantage in comparison both to men and to urban women.

Poor Nutrition

The impoverished, rural populations of Tanzania often do not receive adequate nutrition because they are unable to produce enough food for their families. Most of the world’s poor and undernourished are smallholder farmers, which is especially true in Africa.82 Representative data from East Africa suggests that about 58% of caloric consumption in rural households is from one’s own subsistence crops, while the other 42% of calories are from purchased foods.83 Since subsistence crops are not always reliable food sources because of frequent climate and weather fluctuations,84 this puts rural farmers at risk of not being able to access adequate amounts of food. Based on a study comparing trends for the years 2008–2009 and 2012–2013, the caloric intake for urban households remained fairly consistent. Over the same timespan, however, rural households' caloric intake declined significantly. For instance, when a 50% rise in maize prices took place, rural household caloric intake decreased by 12.6% as compared to 5.4% in urban areas.85 This decrease in nutrition following food price shocks is due to the fact that those in rural areas who rely on subsistence agriculture for their food and income are less able to afford these food items after rises in price. Because of this, and because subsistence farmers are limited in what kinds of food they can produce, markets are often necessary to provide variety and quality in a diet. However, rural families’ locations and financial situations limit their access to markets where they can purchase food.86

Data collected from the rural Morogoro region in eastern Tanzania demonstrates that the mean intake of energy per day is inadequate due to a lack of access to the necessary amount and variety of food. The male intake met 52% of the recommended energy intake, while the female intake met 72%.87 Additionally, 92% of households indicated that they rarely consumed milk and dairy products, and essential nutrients such as iron, zinc, and calcium were measured at 40%, 53%, and 64%, respectively, of the recommended intake.88

Limited access to a varied diet also means many pregnant mothers’ diets end up affecting their children, prior to and during pregnancy.89 In rural Tanzania, double the number of children born between December and February (when food insecurity is most prevalent) experience acute malnutrition as compared to those born between June and August (when food insecurity is the least prevalent).90 This demonstrates how a mother’s diet late in the pregnancy can affect the baby’s nutritional health. Rural poverty and lack of access to adequate amounts of food continue to affect children as they grow older. Over 2.7 million Tanzanian children under 5 were estimated to have experienced stunted growth in 2015,91 with an above average rate of rural children experiencing stunted growth as compared to urban children.92

Child Labor

Impoverished families often rely on child labor in order to meet the demands of subsistence farming or to provide additional income for economic stability. In Tanzania, 29.3% of the youth ages 5 to 14 participate in child labor.93 While children may be forced to engage in a variety of work—including mining, quarrying, sex trafficking, and domestic work—approximately 94.1% of the Tanzanian children that participate in child labor work in agriculture.94 In 2014, 92.5% of children in child labor did unpaid family agriculture work, suggesting that they are predominantly children from rural families.95 These children work on the farms in order to help their impoverished families produce enough food for the family to eat.96 Most of the agricultural work they perform involves plowing, weeding, harvesting, processing crops, herding livestock, and tending cattle.97 All in all, rural youth are at a much greater risk of engaging in dangerous work practices and are subject to poor working conditions with low pay, whether in agricultural work or other employment.98 99

The widespread poverty in rural Tanzania forces young children to participate in difficult work inappropriate for their age, often at the expense of gaining an education, which would allow them an opportunity to escape the life of subsistence farming and poverty.100 Child labor interferes with children’s educational attainment by depriving them of school altogether or requiring them to combine school attendance with often excessively long and difficult work days.101 In fact, over 24% of Tanzanian children aged 7 to 14 combine both work and school.102 Without proper education, these children may be limited to low-income employment or subsistence farming like their parents, further cementing their place in the cycle of poverty.

Although Tanzania has child labor laws in place, the nation has made minimal advancements in reducing the practice of child labor. Anectdotal evidence suggests that “not everyone knows of the child labor laws, including families and local officials.”103 Because the government workers responsible for enforcing these laws lack the staff and funds for inspections, the practice of child labor continues without repercussions.104

Practices

Sustainable Organic Farming

Subsistence farming is an essential part of life in rural Tanzania, yet food insecurity and inadequate income make the practice unstable. Additionally, many rural farmers lack adequate knowledge to increase their annual harvest yields. In order to improve the outcomes of subsistence agriculture, organizations are working to establish capacity growth in agriculture and entrepreneurship.105 Certain organizations aim to educate rural farmers, providing them with the skills necessary to grow healthy and resilient crops. Sustainable and organic farming can be accomplished by educating groups of farmers about unsustainable practices that often contribute to food insecurity, poverty, and malnutrition as well as environmental degradation.106

Sustainable Agriculture Tanzania (SAT) is a grassroots organization operating in the Morogoro district in eastern Tanzania that teaches farmers how to organically improve their yields and maintain the health of the soil.107 SAT aims to disseminate proper knowledge of farming practices as well as entrepreneurial and saving/lending skills, all of which builds the capacity of farmers so they can participate in the value chain. SAT spreads this information through a variety of means; they organize face-to-face farmer group practicums in villages using demonstration plots, encourage and empower farmer group attendees to spread the knowledge to other community members, offer demonstrational courses about agroecological practices at its Farmer Training Centre, and distribute a practical and easily understandable monthly farming magazine. Its goal is to accomplish all of this without any additional costs or expenses for the participants.108

Much of this training and skill development is in soil care. Participants are able to learn about biofertilizer with native microbes as well as sustainable waste management and composting.109 They are also taught about conservation agriculture techniques, such as pest and weed management, conservative irrigation, and methods for maintaining crop diversity and soil cover. These practices increase the amount of crop yields, improve soil fertility, and are better for the environment.110 Farmers are also taught about animal health, housing, and feeding.111

Impact

According to SAT, more than 2,000 farmers from 72 farmer groups across the Morogoro district have successfully been trained in organic farming methods in their own villages. More than 1,500 farmers have been trained in sustainable agriculture at the Farmer Training Centre. SAT has assisted 35 farmer groups in establishing village saving and lending systems.112

Recent studies within the organization indicate an average increase in income of 38% for those who attended demonstrations. Sixty-six percent of farmers reported an increase in production, and 61% of farmers reported a reduction of costs for agricultural inputs. Seventy-six percent of the farmers have reported a more balanced diet because their crops are no longer as susceptible to weather vacillations throughout the year, resulting in positive health outcomes for the farmers. Up to 50% of farmers have reported having access to new markets as a result of diversification of organically grown produce.113

In terms of soil health and retention, 64% of farmers reported reusing land and 91% reported using erosion control measures, whereas only 30% had used them prior to taking the training program. Through soil management and water reduction, farmers reported a reduction of 59% in water consumption.114

Gaps

Although the organization illustrates success through output and outcome data and reports positive feedback from participants, the data and responses may not be valid because the means through which the data was gathered are unclear and unreported. No existing data indicates how many of the participants actually practiced and implemented the training, and SAT has reported no impact data in order to establish if the outcomes are a direct result of its interventions. Another significant gap in the reported statistics is that they do not demonstrate how the organization is influencing poverty rates within Tanzania. Other than the 38% increase in farmers’ income, all of the statistics reported by the organization focus on crop yields and more effective farming practices. While more effective farming practices reduce the cost of agricultural production and increase the amount of available food (and therefore may alleviate some aspects of poverty), no specific data illustrates that SAT helps rural farmers escape poverty.

Invest in Livestock Development

Rural Tanzanians are extremely dependent on their livestock to produce food for their families and to sustain their livelihoods. Half of households throughout the nation keep livestock, and 86% of livestock farmers and 95% of poor livestock farmers live in rural areas. Further, animal products contribute 15% of rural families’ income.115 Although the natural resources within the country (such as resilient livestock breeds, diverse vegetation, and extensive rangelands) allow for exceptional livestock development, the livestock sector is not performing according to its potential, as it contributes only 7.4% to the country’s GDP.116 The sector is constrained from producing larger economic gains for rural Tanzanians because of low livestock reproductive rates, high disease prevalence among the livestock, and high livestock mortality.117 Less than a third of family-owned livestock is vaccinated, and 60% of livestock have diseases.118 Organizations that work to improve the health of the livestock and aid rural farmers in efficiently utilizing their livestock can help rural families escape the poverty cycle.

The Tanzania Livestock Modernization Initiative (TLMI) is a government-funded program run through Tanzania’s Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries Development that aims to “harness the potential of the meat, dairy and poultry sectors for poverty alleviation through improvements across the value chains.”119 These improvements, including greater livestock security and disease control, ensure safe and healthy livestock products, therefore improving the livelihoods of livestock farmers and boosting food security. This can also create employment opportunities as farmers are able to expand their livestock count and gain more disposable income. The program aims to improve the market infrastructure and marketing systems within Tanzania, which would allow rural farmers to make more money off of their livestock, thus helping to alleviate poverty on an individual and large scale.120 The TLMI teamed up with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) to form the Tanzania Livestock Master Plan (TLMP) in 2015, which aims to guide government policy and investment interventions in order to enhance livestock production.121 122

Impact

Neither the TLMI nor the team that created the TLMP report any output, outcome, or impact statistics. Although the TLMP was launched in 2015 and planned to produce results by 2016, the only statistics currently available are the projections of what the TLMP hoped to achieve. The plan projected an increase in total milk production by 77% due to its interventions, thereby increasing the dairy sector’s contribution to the national GDP by 75% during the 2017-2022 period.123 It also projected a 52% increase in total red meat production and a 69% increase in pork production from 2017 to 2022, as well as a 666% and 40% increase in chicken meat and egg production, respectively, by 2022.124 Additionally, in 2015, the TLMI reported that the government would invest US $101 million in feed improvements, veterinary services, disease control, and strengthening of the marketing and processing capacity of the dairy sector.125

Gaps

Given that only projection statistics are reported by the TLMI and through the TLMP, there is no way to know how effective this program has been. It is possible that the government is waiting until after 2022 to report the outcomes, meaning that, potentially, none of these interventions have achieved what was predicted. Additionally, once the statistics are reported, it may be impossible to determine to what extent the outcomes were a result of this program rather than other confounding factors because the TLMI has made no mention of conducting a randomized control trial.126

Provide Health Resources to Rural Communities

Because of Tanzania’s limited healthcare services as a result of rural poverty, many community healthcare workers, oftentimes midwives, do not have adequate resources or knowledge to service the women and children where they are. Improved medical resources for the rural poor and necessary to mitigate this consequence of poverty.

Lwala Community Alliance believes that communities must learn to address their own health challenges. Lwala “recruit[s], train[s], pay[s], supervise[s], and equip[s] traditional birth attendants to extend high-quality care to every home.”127 It also incorporates digital services to help these trained healthcare workers track the progress of the mothers as well as the children. Lwala provides onsite training and quality improvement in government health facilities as outlined in the World Health Organization’s building blocks of health systems: “service delivery, health workforce, information systems, supply chain, finance, and governance.”128 As of 2019, Lwala operates only in Kenya,129 but because the circumstances that keep rural populations in poverty are similar in Kenya and Tanzania,130 this practice would also be effective at helping and empowering individuals in rural Tanzania.

Impact

This extensive training on behalf of healthcare professionals appears to be dramatically improving the lives of mothers and their children. This organization has extensive data-driven models and outcomes for its services. Its outcomes and impact are closely recorded and have even been evaluated by a peer-reviewed study tracking child mortality rates in areas in which this program was operating as well as areas in which the program was not operating. The results of the study demonstrated that 105 children under 5 years old died for every 1,000 live births prior to Lwala’s intervention. From 2012 to 2017, after Lwala started implementing its services in Kenya, the child mortality rate dropped to 29.5 deaths per 1,000 live births. Additionally, Lwala’s health workers were five times more likely to “be knowledgeable of the danger signs in pregnancy and early infancy than status quo community health volunteers.”131 These are remarkable impact outcomes and are great improvements as compared to other local regions in the area.132

Gaps

Although Lwala works with the Vanderbilt Institute of Global Health to continue to publish peer-reviewed research on the effectiveness and impact of the organization, significant gaps in the reported data still exist. The statistics show that there was a decrease in child mortality rates after Lwala’s intervention, but because the study did not include a randomized control trial, there is no evidence that this decrease was due to the organization’s practices.133 Other factors—such as the interventions of other organizations, the absence of certain diseases, or the improvement of health technologies—could be the cause of this improvement. Additionally, Lwala is not currently implementing its interventions in Tanzania, so it is uncertain whether the same results that occurred in Kenya would occur among the rural populations of Tanzania. Finally, Lwala’s mission targets the health issues that often arise as a result of poverty. This means that this practice focuses on solving a consequence of poverty rather than the issue of poverty itself.

Preferred Citation: Raleigh, Dan and Madison Coleman. “Perpetuation of Poverty in Rural Tanzania.” Ballard Brief. December 2020. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints