Poor Cancer Prevention and Detection In Zimbabwe

Photo by iStock

By Kenyon Chipman

Published Winter 2025

Special thanks to Jackie Durfey for editing and research contributions.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Summary+

In the wake of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, rates of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), including cancer, have increased. Although HIV/AIDS and other cancer-associated illnesses, such as Human Papillomavirus (HPV), are on the decline in Zimbabwe, these diseases laid the foundation for the rising cancer epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa. While infectious diseases remain major contributors to the development of cancer, poor prevention and detection act as the central catalysts in Zimbabwe’s inflated morbidity and mortality rates. A widespread lack of basic cancer knowledge among both patients and health professionals, along with barriers to resources and services, are the main contributors to poor prevention and detection rates. Ultimately, inadequate efforts result in late diagnoses for patients, leaving them to navigate a complicated, expensive, and uncoordinated healthcare system, which can have lasting negative effects on patients and their families. The most effective way to decrease the number of avoidable cancer deaths in Zimbabwe and other sub-Saharan African nations will come through building partnerships between various organizations to train local health professionals, coordinate nationwide vaccinations, and implement upscale prevention and detection projects.

Key Takeaways+

Though the number of people diagnosed with cancer in sub-Saharan Africa is projected to rise exponentially in the coming years, a significant portion of those cancers are preventable.

It is understood that the diseases HIV and HPV compound cancer; however, many at-risk individuals lack the resources and accessibility to benefit from the preventive and diagnostic care available for HIV and HPV.

Poor prevention and detection of cancer generally leads to late diagnosis, postponing treatment, and decreasing a patient’s likelihood of survival.

Because of Zimbabwe’s resource constraints, cervical cancer screenings and vaccinations against HPV are two of the most valuable tools for decreasing the number of cancer diagnoses and deaths.

Key Terms+

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)— A disease caused by a late-stage HIV infection that has damaged the body’s immune system. AIDS is commonly transmitted through bodily fluids, particularly infected blood.1

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)— A virus that attacks cells that help the body fight infection, making a person more vulnerable to other infections and diseases. If it is not treated, HIV can lead to AIDS.2

Human Papillomavirus (HPV)—The most common sexually transmitted infection. HPV is usually harmless and self-resolving, though some types can cause cancer or genital warts.3

Oncology—A branch of medicine specializing in diagnosing and treating cancer. It includes medical oncology focusing on chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and other drugs; radiation oncology; and surgical oncology.4

Palliative Care—Specialized medical care that focuses on providing relief from pain and other symptoms of a serious illness rather than resolving the issue.5

Radiotherapy—A treatment using high doses of radiation to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors. Internal radiotherapy involves inserting the radiation source inside the patient’s body, whereas external radiotherapy requires a specialized machine. Radiation therapy does not kill cancer cells right away; days or weeks of treatment may be needed before DNA is damaged enough for the cancer to die.6

Stages of Cancer—A way of describing the size of a cancer and how large it has grown.

Stage 1: The cancer is small and contained within the organ it started in.

Stage 2: The cancer is larger than in stage 1 but has not spread into the surrounding tissues.

Stage 3: The cancer has grown to a certain size (depending on the type of cancer) and possibly started to spread into surrounding tissues, infecting nearby lymph nodes.

Stage 4: The cancer has spread from where it started to another body organ, such as the liver or lungs. This is also called secondary or metastatic cancer.7

Sub-Saharan Africa—The term used to describe the area of the African continent that lies south of the Sahara Desert.8

Context

Q: What is the history and current state of cancer in Zimbabwe?

A: Historically, the Zimbabwean government has not prioritized the prevention and treatment of cancer and other noncommunicable diseases due to the prevalence of communicable diseases such as cholera, HIV/AIDS, and malaria.9 However, starting in 1994 with the founding of the National Cancer Control Program (NCCP), the government began allocating more resources to alleviate the growing cancer burden, which now accounts for over one-third of premature deaths from noncommunicable diseases in Zimbabwe.10, 11

According to Zimbabwe’s National Cancer Registry, cervical cancer cases doubled between 2009–2018.12 The Global Cancer Observatory reported 20% of Zimbabweans may develop cancer before the age of 75, and 15% risk dying from the disease by that age.13 In contrast, surrounding countries report lower rates with a 16.2% risk of developing cancer in Zambia and an 11.8% risk in Botswana. As of 2022, the three most prevalent types of cancer in Zimbabwe were cervical, breast, and prostate.14 That same year, 17,725 cancer diagnoses and 11,739 cancer-related mortalities occurred.15

Cancer continues to rise in Zimbabwe and the rest of sub-Saharan AfricaThe term used to describe the area of the African continent that lies south of the Sahara Desert.8. Diagnoses were projected to double between the years 2020 and 2030 in this region of the world while this rate was predicted to increase by 45% from 2010 to 2030 in the United States.16, 17 Additionally, the World Health Organization (WHO) predicted the number of cancer incidences in sub-Saharan Africa to exceed one million per year by 2030.18 This expected rate would equate to the whole city of Dallas, Texas, in the United States or the entire population of the sub-Saharan country of Eswatini contracting cancer in one year.19, 20 The WHO attributes the uptick in cancer cases to behavioral risk factors and limited access to early diagnostic treatment and palliative careSpecialized medical care that focuses on providing relief from pain and other symptoms of a serious illness rather than resolving the issue.5.21 Additional sources identify other contributors to the growing rates of cancer-associated communicable diseases, such as an aging population and unhealthy lifestyle choices.22

The increase in cancer throughout Zimbabwe correlates with an increase in the suffering of civilians. One measure used to quantify suffering is called serious health-related suffering. This measure refers to suffering that inhibits normal function and can be relieved only through professional intervention.23, 24 Collectively, low-income countries, including Zimbabwe, are predicted to experience a 155% increase in serious health-related suffering by 2060, compared to 57% in high-income countries, with cancer projected to be a leading cause.25, 26

Q: Who is most affected by cancer in this region?

A: While cancer is indiscriminate of gender, race, nationality, age, social class, income, or any additional societal, physical, or other divisions, cancer does affect certain groups more than others.

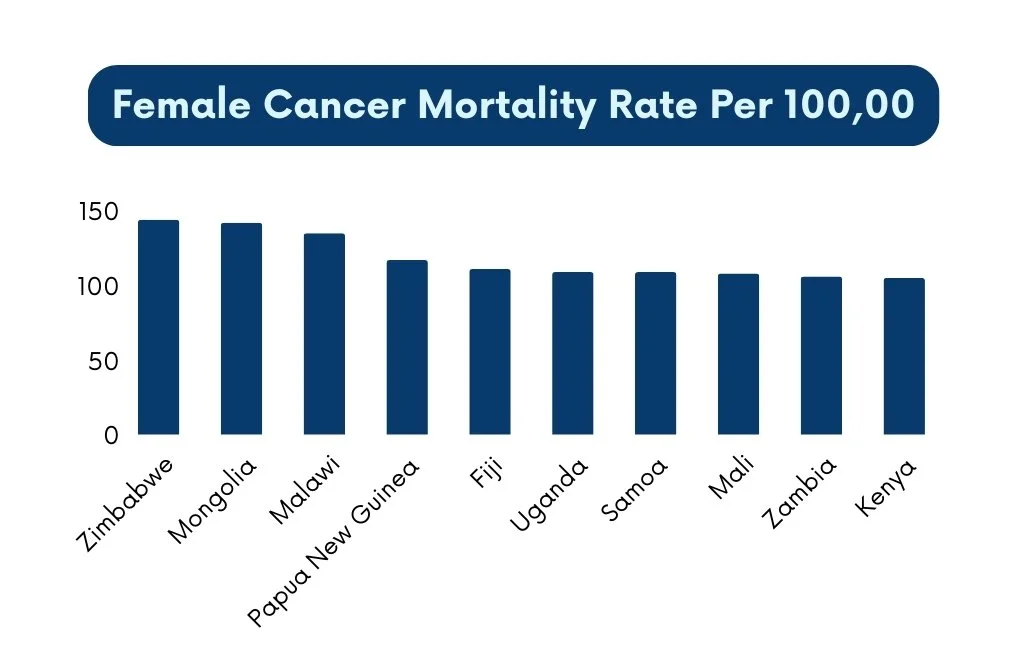

Despite having a lower cancer incidence than many other countries, Zimbabwe experiences an abnormally high cancer mortality rate. Zimbabwe's cancer incidence is measured at 203.1 per 100,000 people compared to Denmark and the United States, which are 349.8 and 303.6 per 100,000 people, respectively.27 Unfortunately, regardless of low cancer incidence numbers, Zimbabwe's cancer mortality for both sexes reached about 144 per 100,000 people in 2022.28 In a survey of 175 countries, this 2022 statistic ranked Zimbabwe as one of only five countries to have a collective mortality rate above 130.29

Regarding gender, Zimbabwe presents a global anomaly. According to the World Cancer Research Fund International Statistics, the cancer mortality rate for Zimbabwean women was the highest in the world in 2022, with 149 deaths for every 100,000 women in the nation.30 In comparison, the rate for Zimbabwean men was 140 deaths for every 100,000. In that same year, 6,334 new cases of cancer were diagnosed in men and 10,978 in women.31 These figures highlight that not only is cancer more common among women, but they also face a notably higher risk of death. In fact, women in Zimbabwe have a 5.67% higher relative risk of death than men.32

Cervical cancer is the most common cancer among women of all races and ages in Zimbabwe, accounting for 19% of all cases. 33 This number is likely higher than the actual quantity reported because Zimbabwe’s National Cancer Registry (ZNCR) draws its data from urban cities, and 68% of the population lives in rural areas.34 Despite likely inaccuracies, in 2020, the ZNCR reported that 29.4% of all cancer cases in the country were attributed to women who had developed cervical cancer.35

Photo: Fietzfotos, Pixabay

Nearly 80% of cervical cancer cases originate worldwide in developing countries such as Zimbabwe, and for many African countries, cervical cancer is a leading cause of death for women.36, 37 As of 2023, approximately 5.24 million women in Zimbabwe were at risk of developing cervical cancer each year, meaning they fell within the susceptible age range or had risk factors that increased their likelihood of the disease. Each year in Zimbabwe, approximately 3,043 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer, and approximately 1,976 die from it.38 The mortality rate of women diagnosed with cervical cancer in Zimbabwe has been reported as high as 64%.39 Some scholars have concluded that the death rate peaked due to the late manifestation of cases, failure to complete treatments due to lack of resources, and issues with treatment facility availability and affordability.40, 41

Still, gender is not the sole factor driving disparities in cancer rates across Zimbabwe. Within the country itself, cancer disproportionately affects citizens of certain races. Researchers found that ethnicity significantly influences cancer prevalence and survival outcomes, with African-Albino patients facing a 17.59% higher risk of death and Asian patients experiencing a 52.42% higher risk compared to the average African patient. Whereas Europeans have a 56.31% lower mortality risk.42 Studies comparing race and gender also showed that Black African women are at higher risk of developing cervical cancer than Caucasian Zimbabwean women.43 To provide context, approximately 98% of Zimbabwe’s population is Black, 1% is White, and 1% is Asian or of mixed racial background.44

Different types of cancers impact both men and women, within Zimbabwe's many ethnic subsects to varying degrees. In 2009, cervical cancer surpassed other common cancers for black women in Zimbabwe by a considerable amount, composing 33.5% of cases, with breast cancer at 11.7%, Kaposi’s sarcoma at 8.9%, eye cancer at 6.5%, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma at 4.9%. Kaposi’s sarcoma affected black men more than any other cancer (20.8%), with prostate (13.7%), esophagus (6.3%), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (6.2%), and liver (5.7%) cancers following. For nonblack men and women, the most common type was non-melanoma skin cancer at 50.7% and 35.4%, respectively.45

Q: What challenges in Zimbabwe’s healthcare system affect cancer patients?

A: The complex and inconsistent healthcare system in Zimbabwe can present many challenges for cancer patients trying to receive treatment. A shortage of specialists, a backlog of needed surgeries due to limited equipment, staff, and time, as well as the need to import medications, all complicate the care experience for cancer patients. In addition to these issues, Zimbabwe has few functioning radiotherapyA treatment using high doses of radiation to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors. Internal radiotherapy involves inserting the radiation source inside the patient’s body, whereas external radiotherapy requires a specialized machine. Radiation therapy does not kill cancer cells right away; days or weeks of treatment may be needed before DNA is damaged enough for the cancer to die.6 machines, meaning patients must travel to major cities in Zimbabwe, like Harare or Bulawayo, for treatment.46 The referral system, meant to assist in the smooth transition of patients and their records between healthcare providers, faces challenges that compound these shortages. In one survey, participants reported that by the time they received a diagnosis and engaged in treatment, they had been referred to so many different health facilities and service providers that their disease had advanced to the next stage of cancer.47 One patient reported being referred to another hospital after waiting two weeks for a biopsy, only to find that the doctors at the new hospital were on strike and unable to provide service while the disease continued to worsen. The referral system is marked with fees along each step of the way for every service available, creating a financial challenge for patients.48

This financial challenge is worsened by the reality that an estimated 90% of Zimbabweans lack medical insurance, and, due to harsh socioeconomic conditions, many are unable to pay for services out of pocket.49 The average wage in Zimbabwe is approximately $253 a month.50 This statistic considers the 30% of the population who are officially employed, excluding the other 70% of the population who have to survive through their own means. Therefore, the average citizen’s monthly income is likely much less than $253.51 On average, Zimbabwean women living with cervical cancer reported paying $1,620.93 for treatment, with some reporting payments of up to $3,000 for a complete treatment cycle. Several surveyed patients reported that their primary concern following diagnosis was how they would secure funding for treatment.52 In one study, 85.2% of patients failed to purchase prescribed medications, and 91.4% reported that the medications were unavailable when they needed them. Patients who could find and pay for medications reported that chemotherapy drugs were only available at private pharmacies at $100–$1,000 per cycle, with some patients requiring up to twelve cycles.53, 54 Of the patients surveyed, 8.6% reported having medical insurance.55 Due to medicine scarcity, chemotherapy is rarely found at the few hospitals that treat cancer.56 In a survey of pharmacies in Harare, the capital city, anti-cancer drug availability presented a more pressing problem than pricing. For example, cancer medications saw a 36% mark-up—pharmacies sold the drugs for 36% more than the purchase price—compared to 82% for medicines such as antipsychotic drugs; however, despite lower mark-ups, anti-cancer drugs were much harder to come by, with 10% of pharmacies having them in stock.57 The lack of adequate resources for cancer treatment leads those who can afford it to look outside the country. However, those who can afford such measures are in the vast minority, as travel costs alone can make treatment unaffordable for those who must travel repeatedly to one of the two radiation treatment centers in Bulawayo or Harare for weeks- or month-long treatment regimens.58, 59, 60, 61

For many Zimbabweans, the high cost of medication forces difficult decisions that disrupt treatment and lead some to seek alternative, less effective remedies. Some Zimbabweans reported they ended their treatment cycles early because they did not have the money for medication, so they had to take breaks from their treatment cycles to save up the money to begin treatment again.62 Patients also tended to give up on medicine and go to traditional and spiritual healers who offered more affordable but ineffective treatments.63

Q: How does cancer prevention and detection in Zimbabwe compare to other countries?

A: In 2018, Eastern Africa (including Zimbabwe) suffered 394,000 cancer cases, the highest number for any other region in Africa.64 For cervical cancer specifically, 68 out of every 100,000 women in Zimbabwe are diagnosed annually. As of 2020, the rate is ten times lower in women in the United States, at 6.8 out of every 100,000.65, 66 Thirteen of every 100,000 US women developed cervical cancer in the 1970s, meaning in 35 years, those cases decreased by 52%.67 In contrast, data from the city of Bulawayo showed the cervical cancer rate for Zimbabweans was 81.8 per 100,000 between 2011–2015, rising from 25.8 per 100,000 between 1968–1972. These statistics represent a 287% increase in incidence from the 1970s to the 2010s.68, 69 Such disparities in cancer occurrences between Zimbabwe and the US allude to variations in contributing factors as well as in prevention and detection efforts across countries.

High-income countries (HICs) have greater access to cancer screening and treatment options, while low- to middle-income countries (LMICs) such as Zimbabwe have limited access, perpetuating high rates of preventable cancer-related deaths. By 2040, 69% of global cancer deaths are predicted to occur in LMICs.70 Between 2000–2015, many HICs implemented improved prevention, early diagnosis, screening, and treatment programs, which contributed to a 20% reduction in premature cancer deaths. LMICs saw a 5% reduction in comparison.71 A large differential exists in access to primary care and cancer referral systems between HICs and LMICs, with 90% of HICs having comprehensive treatment services versus 15% of low-income countries.72 Additionally, LMICs tend to lack adequate data required to better respond to trends in cancer incidence.73

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) administers the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP), a comprehensive initiative that supports all 50 states and several U.S. territories in providing breast and cervical cancer screenings to low-income, uninsured, and underinsured women. Additionally, women who are diagnosed through the NBCCEDP can qualify for Medicaid treatment.74 While Zimbabwe’s screening programs are free, access to these programs remains uneven. As of 2019, 20% of the population had access to screening services, with 10% access in rural areas and 3% access in urban areas.75 By comparison, some European nations, such as Denmark and Sweden, screened over 80% of 50–69-year-old women in the country for breast cancer.76 Data for the total percentage of the vulnerable population in Zimbabwe who received breast cancer screenings does not appear to be reported. Although the Ministry of Health and Child Care promoted breast and cervical cancer screening for women of reproductive age in the Mutare District, uptake remained low due to concerns about long wait times, associated costs, screening duration, and other perceived barriers.77

Contributing Factors

Lack of Cancer Knowledge

Misconceptions and limited knowledge about cancer among both patients and healthcare workers contribute to poor prevention efforts and delayed detection. Specifically, people in Zimbabwe are not aware of how essential early cancer screening is. In the rural Chegutu district, a cross-sectional questionnaire survey found that 41% of Zimbabwean citizens had little knowledge of available screening services.78 A survey in the Gwanda District found that 21% of women had never heard of the screening program, and another 17% had inadequate information.79

Many women were hesitant to seek cervical cancer screening because they believed that, without symptoms, screening was unnecessary. Given that cervical cancer is a slow-progressing disease and its early stages do not present any symptoms, this attitude can result in long-term health consequences.80 Overall, screening providers attribute low screening rates to a general lack of awareness about cervical cancer.81 This lack of awareness corresponds with a lack of knowledge about available screening programs (even when services are offered locally), the locations of screening sites, the appropriate age to begin screening, and the purpose and benefits of being screened.82, 83, 84, 85

While many people were unaware of screening services and other related programs, one study found that listening to the radio one to six times a week increased the likelihood of understanding the causes of cervical cancer. Knowledge of prevention correlated with daily listening.86 However, general cancer information may not be enough. Many Zimbabweans have adverse feelings toward screening services. A meta-analysis of eight studies showed some women have a low-risk perception of cancer, while others chose not to be screened because of the intimate nature of the screening process, fear of pain, or other myths or misunderstandings.87, 88 Some of these misconceptions found in three of the eight studies include beliefs that the test will involve the removal and reinsertion of the uterus, their vagina will be enlarged, or they will not be able to have children after the screening.89, 90 Three of the studies in the meta-analysis indicated that women were also afraid of stigmatization. These women worried about the reactions of their community and family members, as cervical cancer’s association with HPVThe most common sexually transmitted infection. HPV is usually harmless and self-resolving, though some types can cause cancer or genital warts.3, a sexually transmitted illness, caused people to see the cancer as a disease that solely affects the promiscuous.91

A survey of 751 high school and college students in Zimbabwe revealed widespread misconceptions about cancer. While 87% claimed to know what cervical cancer is, 43% had never heard of prevention and screening, and 53% did not know the intricacies of HPVThe most common sexually transmitted infection. HPV is usually harmless and self-resolving, though some types can cause cancer or genital warts.3 transmission and prevention.92 Evidently, the younger generation has several misconceptions about cervical cancer. Several students in the study expressed incorrect beliefs about the causes of cervical cancer, citing factors such as sexual activity with an uncircumcised male, smoking, the use of bathing soaps, and hair removal products.93 A 2019 cross-sectional survey also found that when the parents are educated, they still rarely share information concerning cervical cancer, proving that parental education levels and children’s knowledge of cervical cancer are not correlated.94

Despite the continuous impact of cervical cancer on the nation’s public health, many citizens have insufficient knowledge of the intricacies of cervical cancer and HPVThe most common sexually transmitted infection. HPV is usually harmless and self-resolving, though some types can cause cancer or genital warts.3.95 Not only that, but there is a lack of understanding concerning other cancers as well. One study showed that only 14% of men in Zimbabwe knew about screenings for prostate cancer. Much like the public awareness surrounding cervical cancer, public understanding of prostate screenings and prevention contains significant misinformation.96 For example, a survey in the Mhondoro-Ngezi region revealed that men were confused about the proper age someone should be screened, with only 11% of men in the study knowing the appropriate screening age for men is 50+.97 Of the men surveyed, 43% incorrectly believed prostate cancer affected only sexually active men.

The knowledge deficit regarding cancer is also prevalent within the healthcare system. A 2023 study revealed that both citizens and health providers—mainly nurses and midwives—had limited information about breast cancer.98 Surprisingly, only approximately 54.5% of healthcare providers understand the prevalence of breast cancer incidences within Zimbabwe.99 One cross-sectional survey on cervical cancer identified several problems within the system, including healthcare professionals who did not understand how to educate the community or what to do when a patient exhibited cancer symptoms. Some rural clinics had nurses who did not know what cervical cancer was.100 For example, according to the data at Harare Hospital, Parirenyatwa Hospital, and Island Hospice, 28% of healthcare workers reported they had not received adequate training in cervical cancer treatment and care.101 Additionally, 38% indicated they had never read the National Cancer Prevention and Control Strategy or the Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control Strategy for Zimbabwe.102 Another reported hindrance is misdiagnosis. A 2023 qualitative review documented how medical professionals inadvertently delayed necessary treatment by mistakenly diagnosing cancer patients with other maladies, including hypertension, boils, ulcers, rheumatism, Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs), and kidney stones. After misdiagnosis, health professionals prescribed ineffective painkillers, antibiotics, and creams.103A needs assessment project in Zimbabwe found that limited knowledge about breast cancer among practitioners at one provincial and six district hospitals led to treatment referral delays of three to six months.104 Most healthcare professionals admitted that training would improve their ability to diagnose breast cancer, with 93% willing to receive increased training if offered.105

Overall, the accumulated knowledge deficit concerning prevention, diagnosis, and treatment plays a prominent role in the insufficient prevention and detection outcomes in Zimbabwe.106

Cancer-associated Communicable Diseases

Cancer-associated communicable diseases such as HIVA virus that attacks cells that help the body fight infection, making a person more vulnerable to other infections and diseases. If it is not treated, HIV can lead to AIDS.2 and HPV contribute to the high cancer incidence rate, overwhelming the available prevention and detection resources. Although the rates of HIVA virus that attacks cells that help the body fight infection, making a person more vulnerable to other infections and diseases. If it is not treated, HIV can lead to AIDS.2, AIDSA disease caused by a late-stage HIV infection that has damaged the body’s immune system. AIDS is commonly transmitted through bodily fluids, particularly infected blood.1, and HPV have plummeted across the globe, sub-Saharan AfricaThe term used to describe the area of the African continent that lies south of the Sahara Desert.8 remains the most highly affected region in the world. Sub-Saharan Africa holds 12% of the world's population, yet it bears 68% of the world’s HIV burden.107, 108 As of 2023, approximately 1.3 million people lived with HIV in Zimbabwe.109 Reasons for high rates of these communicable diseases include poverty, inadequate medical care, lack of prevention, insufficient education, taboo beliefs, multiple sexual partners, and prostitution.110 Approximately 70% of people with HIV in Zimbabwe have experienced some form of social stigma as a result of the infection.111 Social stigma fuels tendencies to hide, deny, or postpone necessary treatment to avoid embarrassment. In addition, poverty engenders an environment that favors the continuation of these devastating illnesses and their many negative health impacts.

HIVA virus that attacks cells that help the body fight infection, making a person more vulnerable to other infections and diseases. If it is not treated, HIV can lead to AIDS.2 and HPVThe most common sexually transmitted infection. HPV is usually harmless and self-resolving, though some types can cause cancer or genital warts.3 are prevalent in many sub-Saharan African countries, and these diseases often lead to the development of cancer. According to a 2017 situation analysis of Zimbabwe, infection with high-risk HPV subtypes—particularly HPV 16 and 18, which are responsible for about 70% of cases—is strongly linked to cervical cancer.112 Overall, high-risk HPV types are associated with approximately 99% of cervical cancer cases.113 HPVThe most common sexually transmitted infection. HPV is usually harmless and self-resolving, though some types can cause cancer or genital warts.3 is compounded by other cancer-associated communicable diseases such as HIV. While HIV does not directly cause cancer, according to the ZNCR report, HIV is associated with 60% of cancers. HIV weakens the immune system, therefore putting the body at greater risk for developing cancer.114 Additionally, once cancer develops, HIV increases the risk of malignancy (spreading to other parts of the body) by 10%.115 Women living with HIV are six times more likely to develop cervical cancer than those without.116 Generally, cervical cancer can take 15–20 years to develop in women with healthy immune systems, but it can onset much faster, 5–10 years, in women with immune systems weakened by HIV.117 In 2020, 1,976 women died from cervical cancer, making it the leading cause of female cancer-related deaths in Zimbabwe.118

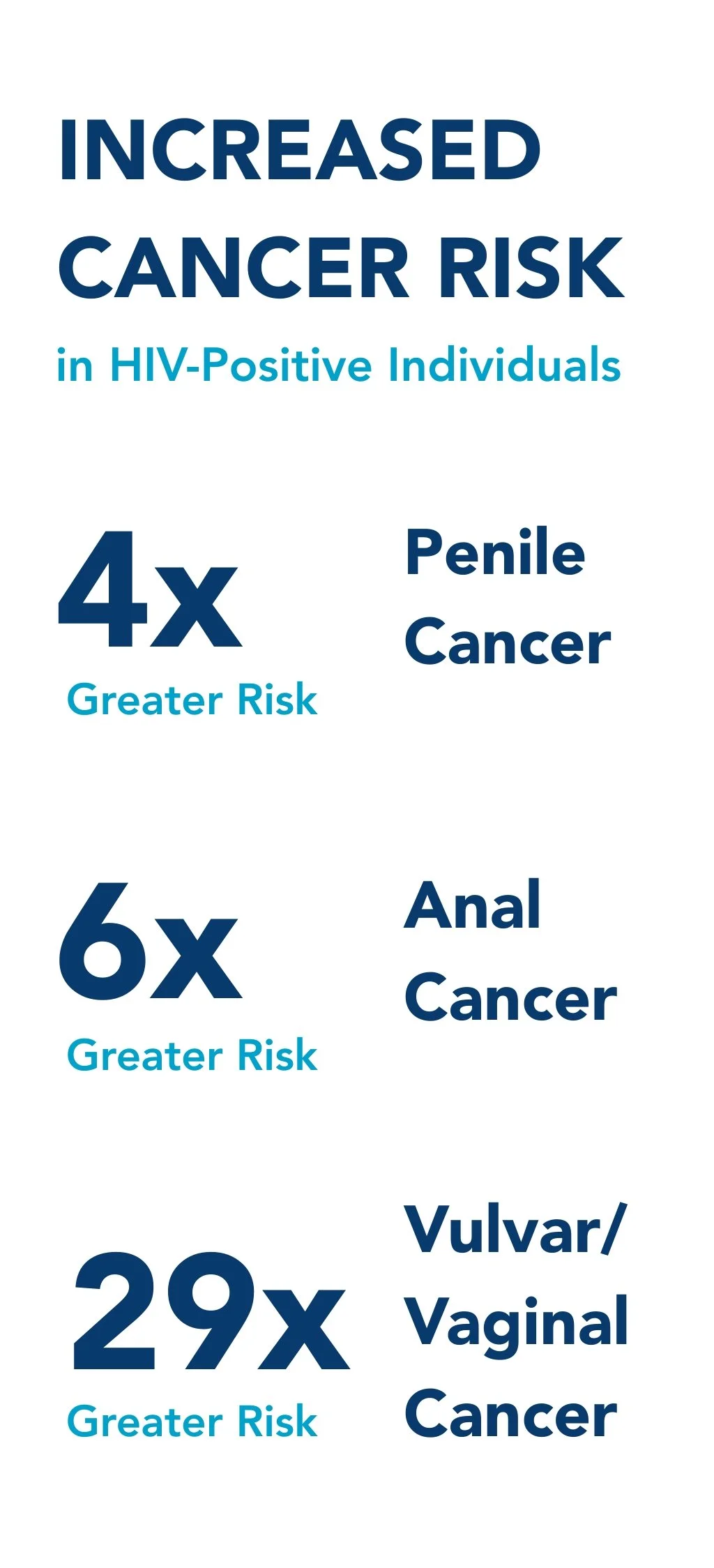

HPVThe most common sexually transmitted infection. HPV is usually harmless and self-resolving, though some types can cause cancer or genital warts.3, especially when occurring alongside HIVA virus that attacks cells that help the body fight infection, making a person more vulnerable to other infections and diseases. If it is not treated, HIV can lead to AIDS.2, can contribute to the development of several cancers beyond cervical cancer. Increasing evidence shows that HPV has a role in many anogenital cancers, including of the anus, vulva, vagina, and penis.119 Research connects certain high-risk types of HPV to head and neck cancers, such as oropharyngeal cancer. Studies have also associated HPV 16 with cancer in the tonsils, the base of the tongue, and other areas.120 HIV-infected individuals also have a higher risk for many of these cancers compared to the general population, including: four times greater for penile, 29 times for anal, and six times for vulvar and vaginal cancers.121

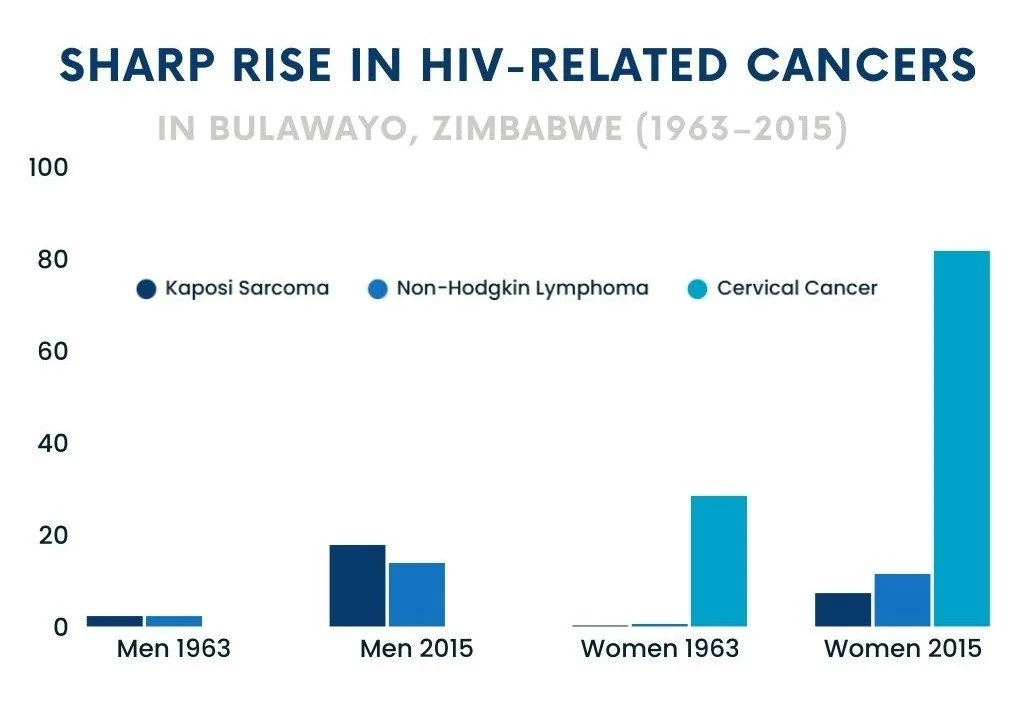

A second epidemic is emerging from the original HIVA virus that attacks cells that help the body fight infection, making a person more vulnerable to other infections and diseases. If it is not treated, HIV can lead to AIDS.2 crisis: a significant rise in HIV-associated cancers, disproportionately affecting low- and middle-income countries such as Zimbabwe.122 A study conducted in Bulawayo compared cancer incidence and HPVThe most common sexually transmitted infection. HPV is usually harmless and self-resolving, though some types can cause cancer or genital warts.3 types from two distinct periods—1963 to 1972, before the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and 2011 to 2015, after the epidemic had taken hold—using age-standardized rate ratios. These ratios represent the number of people diagnosed with each cancer type per 100,000 individuals per year, regardless of age.

The study revealed a shift in cancer patterns. Among men, cancers not linked to HIV, including liver, lung, esophagus, and bladder cancers, declined substantially; for example, liver cancer rates decreased from 51.1 to 9.3 per 100,000, while lung cancer dropped from 46.6 to 4.7. Conversely, HIV-associated cancers increased dramatically, with Kaposi’s sarcoma rising from 2.3 to 17.8, prostate cancer from 21.4 to 55.4, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma from 2.3 to 13.9 per 100,000. A similar pattern was observed among women, with declines in liver and bladder cancers and sharp increases in HIV-related cancers such as cervical cancer, which nearly tripled from 28.5 to 81.8 cases per 100,000, breast cancer rising from 12.3 to 33.1, non-Hodgkin lymphoma increasing from 0.6 to 11.5, and Kaposi’s sarcoma from 0.3 to 7.3 per 100,000. 123 HIV/AIDS accentuates the risk for Kaposi’s sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and cervical cancer. These three cancers are called “AIDS-defining conditions,” indicating that if an HIV-positive person develops one of these cancers, their HIV has likely developed into AIDSA disease caused by a late-stage HIV infection that has damaged the body’s immune system. AIDS is commonly transmitted through bodily fluids, particularly infected blood.1.124 These findings highlight how the HIV epidemic continues to influence the cancer landscape in Zimbabwe, with the growing burden of HIV-related cancers posing an ongoing public health challenge, particularly in settings with limited access to early screenings and treatment.

The HIVA virus that attacks cells that help the body fight infection, making a person more vulnerable to other infections and diseases. If it is not treated, HIV can lead to AIDS.2 epidemic has fueled a dramatic rise in cancer cases in Zimbabwe, particularly through HIV-associated cancers like Kaposi’s sarcoma. From 1995 to 2010, Kaposi’s sarcoma cancer increased twentyfold in Uganda and Zimbabwe, becoming the most common cancer in men and second only to cervical cancer in women.125 This rise is largely due to HIV, as people with HIV are 1,000 to 5,000 times more likely to develop Kaposi’s sarcoma than those without. HIV-related Kaposi’s sarcoma also leads to higher risks of death and other serious health problems.126 In addition to HPV and HIV, other cancer-causing infections include hepatitis B & C viruses, Epstein-Barr virus, and Helicobacter pylori.127, 128 Zimbabwe’s history with cancer-associated communicable diseases offers valuable context and framing for cancer’s prevalence in the country today, as well as the struggle to treat it.

Accessibility of Early Detection and Prevention Services & Resources

Poor accessibility to early detection and preventive services is a proven contributor to insufficient and ineffective preventive efforts. In this instance, accessibility refers to both the financial and geographical aspects of cancer screening and prevention services.

Financial barriers significantly limit access to preventive screening services, as high costs at many private institutions deter individuals from seeking timely screenings.129 At private institutions, screening services such as a visual inspection with acetic acid and cervicography (VIAC) and Pap smears cost approximately $20 and $60 USD, respectively.130 Free screenings are available, but they often come with direct or hidden costs. According to a 2017 study, of the 514 participants surveyed, 91% had not been screened for cervical cancer.131 For example, high transportation expenses, time spent traveling, and long wait times frequently discourage many people from taking advantage of these public health services.132 According to a 2023 qualitative study, individuals in the Manicaland Province of Zimbabwe are often unable to receive treatment when they do make the effort to go to screening sites due to equipment shortages and long wait times.133 Many who cannot afford to travel must wait for outreach teams to visit their local area. However, the infrequency of these visits, along with limited resources and competing priorities, often prevents people from receiving the necessary screenings.134

Photo: Safari Consoler, Pexels

In a study on screening accessibility, women in one rural area in Gwanda District reported that the cancer outreach team would come from Gwanda City once a year, and when they came, the outreach team would focus on HIVA virus that attacks cells that help the body fight infection, making a person more vulnerable to other infections and diseases. If it is not treated, HIV can lead to AIDS.2-positive mothers instead of all who may belong to the at-risk population.135 In the same Gwanda District, women living in rural and mining areas farther from the city reported that the sole location for cervical cancer screening was in Gwanda, the major city in the district, as their local clinics did not have the necessary resources. Of the Gwanda district’s 30 health facilities, free VIAC services are provided at only two sites, both situated exclusively in Gwanda town: the provincial hospital, offering comprehensive services since 2013, and a Council-run clinic, providing basic services since 2020.136 These women also said they did not have the funds to travel to Gwanda for the screenings.137 Additionally, approximately 74% of the rural participants had never been screened compared to 62.1% of urban participants.138 Overall, closer proximity to services in Gwanda was associated with higher screening rates.139 When women were asked why they had never been screened for cancer, the second highest reported answer at 17.6% was that local clinics did not provide screening.140

Limited funding for cervical cancer programs also limits accessibility. Lack of adequate funding results in insufficient resources for screening, including equipment shortages and broken-down equipment.141 Public clinics face shortages of gloves, fluorescent lights, acetic acid, and vaginal speculums.142 Inadequate funding also frustrates efforts to follow up on the results of completed screening tests, negating the original purpose of the test.143 There are 106 VIA/VIAC screening clinics nationwide, representing only 14% of government health facilities that offer cervical cancer screening.144 Additionally, 78% of these VIAC clinics lack backup systems for major equipment.145 An insufficient number of medical personnel also plays a role in overall accessibility. During 2021 and 2022, more than 4,000 nurses, doctors, and other health professionals left the country.146 Retaining healthcare workers remains a challenge due to a lack of economic incentives, working conditions, and workload issues.147 Available healthcare workers are often overworked and have other tasks that reduce their ability to focus on cancer screening.148 In Harare, Zimbabwe, 88% of health workers have noticed personnel shortages, and 53% believe most cervical cancer patients cannot access proper care.149 A lack of personnel means the number of healthcare workers available cannot keep pace with patient demand.150, 151

Socially, the lack of emotional support from family also results in the underutilization of screening services.152 Culturally maintained by a patriarchal and conservative structure, men in Zimbabwe generally continue to make decisions on the health of the women in their lives regarding money for fees or even the decision to seek medical attention.153

Consequences

Late Diagnosis

Late diagnosis is a significant consequence of inadequate prevention and detection efforts. When cancer is identified too late, treatment becomes more costly and complex, survival rates decline, and many patients are left with only palliative rather than curative care options.

The frequent late diagnosis of cancer in Zimbabwe has proven to be a serious consequence of inadequate healthcare systems within the country, severely limiting treatment options and worsening patient outcomes.154 A national cervical cancer needs assessment conducted in two provinces of Zimbabwe found that 76% of cervical cancer cases diagnosed at healthcare facilities were already in advanced stages.155 Similarly, more than 80% of Zimbabwe’s breast cancer cases were not identified until either stage three or four of the disease.156 Overall, statistics for other cancers generally reflect the same trend, as 80% of patients present in third- or fourth-stage progressions.157

When patients are diagnosed in late stages, the chances of a successful treatment outcome decline.158 In a 2023 survey of the Bulawayo Metropolitan Province, 85% of cancer patients had to visit five or more doctors before reaching a diagnosis, and 95.5% had to wait at least three months after diagnosis to begin treatment.159 Delays in cancer detection in Zimbabwe frequently lead to diagnoses at later stages, when the disease is more difficult to treat.160, 161 For example, between 2020 and 2029, it is estimated that 416,000 women will die from breast cancer in sub-Saharan AfricaThe term used to describe the area of the African continent that lies south of the Sahara Desert.8, but one third of these deaths could be prevented by earlier diagnosis.162 Undesirable symptoms, including high levels of pain, sexual dysfunction, weight loss, lack of energy, and various mental and emotional concerns, affect almost 50% of patients who are diagnosed at more advanced stages of cancerA way of describing the size of a cancer and how large it has grown. Stage 1: The cancer is small and contained within the organ it started in. Stage 2: The cancer is larger than in stage 1 but has not spread into the surrounding tissues. Stage 3: The cancer has grown to a certain size and possibly started to spread into surrounding tissues, infecting nearby lymph nodes. Stage 4: The cancer has spread to another organ such as the liver or lungs.7.163 Due to Zimbabwe’s late identification of cancer, many of these patients must resort to palliative care. Palliative careSpecialized medical care that focuses on providing relief from pain and other symptoms of a serious illness rather than resolving the issue.5 aims to ease symptoms and enhance well-being, though it is not curative for cancer.164, 165 In 2014, approximately one in 60 people needed palliative care in Zimbabwe compared to one in 53 people in the US.166, 167 Unfortunately, the high rate of late-stage cancer diagnoses in Zimbabwe significantly limits treatment options, leading to poorer outcomes and an increased reliance on palliative rather than curative care.

Increased Burden on Healthcare System

The poor prevention and detection of cancer result in an increased strain on Zimbabwe’s healthcare system. As of 2020, 10.1% of Zimbabwe’s annual budget is allocated to healthcare expenditures. Although it is an increase from 7% in 2019, this number is below average for countries in sub-Saharan AfricaThe term used to describe the area of the African continent that lies south of the Sahara Desert.8; the rate is 15% in South Africa and 17% for Botswana.168, 169, 170 Cancer treatment puts the already underfunded healthcare system under even more pressure, as the resources required to meet these needs within the country are in short supply.171 Additionally, lasting effects from the 2008–2019 economic crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic still affect the healthcare system today. 172

Photo: Pietro Jeng, Pexels

The strain on Zimbabwe’s healthcare system is evidenced by the cancer patient-to-medical-staff ratio. In 2020, 14 practicing oncologists were available to address the needs of 14.8 million Zimbabweans, making each oncologist responsible for the cancer needs of over 1 million people.173 By comparison, inside the United States, there is one oncologist for every 26,418 people, representing a workload approximately 40 times lighter than that faced by oncologists in Zimbabwe.174175 In addition to oncologists, cancer treatment requires many other health workers, including surgeons, radiologists, nuclear medicine physicians, and medical physicists. In 2020, Zimbabwe had 2.9 medical physicists, 45.8 surgeons, 3.4 radiologists, and 1.1 nuclear medicine physicians for every 10,000 patients.176 In contrast, per 10,000 cancer patients, Sweden had 49.3 medical physicists, 642.2 surgeons, 251.0 radiologists, and 12.0 nuclear medicine physicians in 2020.177 Sweden’s healthcare system, renowned for its high cancer survival rates, has a ten-year survival rate of 70% for diagnosed patients.178

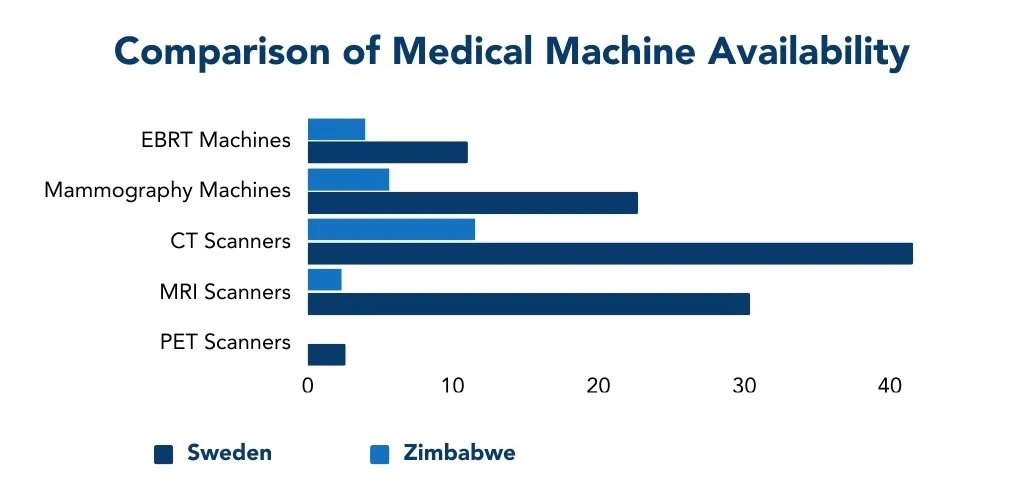

Similar to the data on healthcare workers, the treatment deficit can be observed through available cancer treatment equipment or a lack thereof. For every 10,000 cancer patients, Zimbabwe has four radiotherapyA treatment using high doses of radiation to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors. Internal radiotherapy involves inserting the radiation source inside the patient’s body, whereas external radiotherapy requires a specialized machine. Radiation therapy does not kill cancer cells right away; days or weeks of treatment may be needed before DNA is damaged enough for the cancer to die.6 machines compared to Sweden’s 11. Zimbabwe’s average of 5.7 mammography units per patient represent about one-quarter of Sweden’s 22.7. The country of Zimbabwe also has an average of 11.5 CT scanners per patient—less than one-third of Sweden’s 41.6. MRI scanners number 2.3 in Zimbabwe, compared to 30.4 in Sweden. Zimbabwe has no PET scanners, while Sweden has an average of 2.6 per patient.179, 180

Moreover, Zimbabwe’s current radiation therapy resources do not meet the estimated needs of cancer patients in the country. An estimated 60% of all cancer patients will require radiation treatment at some point in their treatment regimen.181 In 2022, the cancer registry recorded 17,725 new cases in Zimbabwe, meaning over 10,000 of those patients will likely need radiation treatment.182 However, the healthcare system is not equipped to meet this need. Zimbabwe has two functioning public health centers for diagnosing and treating cancer.183 In 2020, four radiation machines were available, but by 2021, only one radiation machine functioned well enough for treatment. The other machines had broken down.184 The healthcare center operating the functional machine reported patients lining up as early as 2 a.m. for treatment, with as many as 200 patients turned away daily.185 After two and a half years of radiotherapyA treatment using high doses of radiation to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors. Internal radiotherapy involves inserting the radiation source inside the patient’s body, whereas external radiotherapy requires a specialized machine. Radiation therapy does not kill cancer cells right away; days or weeks of treatment may be needed before DNA is damaged enough for the cancer to die.6 shutdown, Parirenyatwa Group of Hospitals, the largest hospital complex in the country, resumed radiotherapy treatment of cancer patients in June 2024. While the unit has the capacity to treat 60 patients daily, currently only ten patients are treated each day because of limited personnel trained to operate the machine. Therefore, patients with urgent conditions are prioritized.186, 187 This significant gap between demand and capacity highlights the growing burden on Zimbabwe’s healthcare system, driven by limited access to cancer prevention and treatment services.

Adverse Effects on Individuals and Families

Zimbabwe’s delayed cancer treatment and prevention system causes a significant financial, emotional, mental, and social burden for patients and their families. In the general Zimbabwean population, a cancer diagnosis is seen as a death sentence.188

Given Zimbabwe’s economic challenges, the financial cost of cancer treatment is a major concern for many patients.189 Zimbabwe lacks formal out-of-hospital care support systems for individuals with advanced cancers, resulting in a reliance on immediate and extended family for caregiving. Often, this reliance results in patients draining the sparse financial resources of families.190 Despite the availability of free treatment in Bulawayo and Harare, the surplus of patients needing care overwhelms the capacity of these public radiation centers.191 The other option is to seek private care, which is expensive. A survey of 32 antineoplastic drugs available in Zimbabwe’s private sector found that 10 were classified as unaffordable or highly unaffordable, as their prices exceeded the equivalent of 20 days’ wages for the lowest-paid government worker; the most expensive drug was priced at the equivalent of 490 days’ wages.192 With limited medical insurance coverage among cancer patients, the financial load of treatment often falls directly on patients and their families. These expenses can result in heavy financial burdens that can cause a decrease in the total household income, reduced social and recreational expenditure, the selling of assets, and borrowing of money.193 Financial challenges escalate when an individual who acts as the family’s primary source of income must leave employment due to cancer. In addition to losing employment opportunities, some must leave education or postpone plans to start families.194 In a systematic review of cancer patients in Zimbabwe, 52.6–74.1% of those surveyed reported a reduction in their income, and 63% reported financial difficulties.195

Photo: Muhammad-Taha Ibrahim, Pexels

Furthermore, cancer places new stress on relationships. Culturally maintained by a patriarchal and conservative structure, men in Zimbabwe generally continue to make decisions on the health of the women in their lives regarding money for fees or even the decision to seek medical attention.196 Some single adult patients also face alienation from family and community, as a cancer diagnosis is seen as evidence of promiscuous behavior.197 Many Zimbabweans are not aware of how cancer works, so they isolate family members under the false notion that this disease is contagious.198 In many cases, cancer divides families. According to a 2021 study conducted in Harare, 58% of the participants believed that cervical cancer was caused by witchcraft and is a death sentence.199 Such misconceptions contribute to a culture of shame surrounding cancer, which often exacerbates relationship difficulties. Some women who are diagnosed with cervical cancer are abandoned by their husbands, who seek to remarry healthy wives. Such actions can lead patients to develop mental illnesses and lose the will to live.200 However, a cancer diagnosis also has the potential to bring families closer together, thereby contributing to better outcomes for married patients.201 A 2021 analysis of cancer patients supported this notion by observing that median survival times differed by marital status, with divorced patients surviving a median of 517 days compared to 959 days for married patients.202

Regardless of the relationship between caregiver and patient, cancer often presents challenges for those providing care at home. For instance, a World Health Organization (WHO) study focusing on caregivers of terminally ill patients found that 58% reported insufficient resources, 44% experienced loss of patient employment, and 29% reported neglect of the patient’s children.203 Additionally, in a 2019 survey involving survivors of breast cancer in Gweru, Zimbabwe, 70% of the participants expressed challenges with sexual intimacy due to the negative side effects of treatments.204 Moreover, 60% reported that increased fatigue impacted their ability to care for their families and fulfill traditional roles that are common for a housewife in Zimbabwe.205

Both patients and caregivers tend to have higher rates of depression and anxiety.206 Among women diagnosed with cervical and breast cancer, patients reported experiencing a loss of female identity, feelings of incompleteness or diminished femininity, and concerns regarding their relationships with their partners.207 A 2022 systematic review on the quality of life among cancer patients found that 72.3% reported negative body image, while 44.2% experienced symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.208

Practices

In light of the rising number of cases in Zimbabwe, the country's cancer control coordinator stated that a focus on “high-impact, low-cost interventions” at the prevention and detection level are the most effective long-term.209 Vaccinations against HPVThe most common sexually transmitted infection. HPV is usually harmless and self-resolving, though some types can cause cancer or genital warts.3 and cervical cancer screenings are the best options due to Zimbabwe’s resource constraints.

Vaccination Campaign

Since HPVThe most common sexually transmitted infection. HPV is usually harmless and self-resolving, though some types can cause cancer or genital warts.3 is the leading cause of cervical cancer and contributes to a variety of other cancers, Zimbabwe’s National Cancer Program and partnering NGOs focus on prevention through HPV vaccinations.

Photo: RF._.studio, Pexels

Initially, HPVThe most common sexually transmitted infection. HPV is usually harmless and self-resolving, though some types can cause cancer or genital warts.3 vaccinations were solely available in the private health sector, costing approximately $180–$300.210 Starting in 2014, Zimbabwe received funding from the Global Alliance for Vaccination and Immunizations to implement a cervical cancer prevention-focused HPV vaccine campaign for young girls. The campaign was first piloted in two districts, Beitbridge and Marondera, before widespread use.211 A newly licensed HPV vaccination, HPV2 (also known as Cervarix), was introduced into the public sector for this project. 212, 213 The project targeted ten- to 14-year-old schoolgirls.214

Impact

The first general vaccination campaign in May 2018 achieved 83% administration coverage through sessions in schools across the country. Health professionals administered the second dose in May of 2019, achieving 67% coverage. In total, the project delivered 751,367 doses in 2018 and 801,887 in 2019.215 While no data on the effectiveness of this project exists as of yet, Cervarix proved to be very effective when fully implemented in the testing period, protecting against 75–80% of cervical cancers.216

Gaps

As a preventive vaccination effort, the Global Vaccine Alliance cannot measure impact this early on after the vaccination campaign. However, future comparisons of rates of cervical cancer incidence between groups that did and did not receive the vaccine will be able to determine the overall impact of the vaccination campaign. Since HPVThe most common sexually transmitted infection. HPV is usually harmless and self-resolving, though some types can cause cancer or genital warts.3 vaccination campaigns are a preventive approach that aims to protect ten- to 14-year-old girls, the true impact is temporarily unknown because the disease does not present until later in life.

Additionally, while HPV2 could potentially protect against 80% of cervical cancers, the HPV2 vaccine still leaves potential gaps in cervical cancer prevention. For example, HPV is caused by numerous genotypes, and although types 16 and 18 are responsible for about 70% of cases, the remaining cases are linked to other high-risk types.217 The vaccine used in Zimbabwe, the HPV2 vaccine (Cervarix) is effective in preventing cervical cancer that stems from HPV 16 and 18. However, these vaccines do not protect against other high-risk HPV types that are common in Zimbabwe, such as types 31, 33, and 58. Due to this lack of coverage, vaccines like the HPV2 vaccine, though beneficial, do not offer complete protection against cervical cancer.218 Some people may still get limited protection from these other types of HPV (called cross-protection), but this is not guaranteed, particularly because 17% of cases involve more than one HPV type.219 As a result, even with vaccination, a significant portion of cervical cancer risk remains unaddressed, highlighting the limitations of relying solely on HPV2 as a preventive strategy.

Despite where vaccinations are lacking, the outlook is hopeful. Broad-spectrum HPV vaccinations have a precedent of success in other nations of the world, including France, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, the UK, and the US.220 However, these countries do not have as many HPVThe most common sexually transmitted infection. HPV is usually harmless and self-resolving, though some types can cause cancer or genital warts.3 genotypes as Zimbabwe, meaning the success achieved in other countries may be difficult to duplicate. African countries like Zambia, Cameroon, Mozambique, and Senegal, with equally diverse genotype pools, have undergone struggles similar to those of Zimbabwe regarding vaccine-related prevention practices. The development of a new HPV vaccine, currently in clinical trials, may protect against genotypes 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 could be more useful in sub-Saharan AfricaThe term used to describe the area of the African continent that lies south of the Sahara Desert.8 than other available vaccine options.221

Preferred Citation: Vaitohi, Brook. “Inadequate Healthcare in Pacific Islands.” Ballard Brief. June 2025. www.ballardbrief.byu.edu.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints