Protracted Refugee Situations in Kenyan Refugee Camps

By Lorin Utsch

Published Summer 2020

Special thanks to Harper Forsgren for editing and research contributions

+ Summary

Kenya hosts over 491,000 refugees fleeing from persecution in some of the largest refugee camps in the world. Though intended as temporary, many refugees find themselves stuck in these camps for years, sometimes even generations, which then grants them the title of “protracted refugee.” This perpetuation of a limbo state is brought on from continuing threats in their country of origin, existing xenophobia in public spheres, and an inability to establish themselves economically or socially outside of the camp. Protracted refugees feel a greater sense of social insecurity, increased mental health challenges, and increased vulnerability that can lead to exploitation. While some organizations are working to find more long-term solutions for these refugees through local integration, others are working to increase global awareness of the need for policy changes as well as establishing peace in the refugees’ homelands. The success of these organizations is promising but needs to be further measured in order to determine the most effective way to help protracted refugees find a permanent home and finally escape exile.

+ Key Takeaways

+ Key Terms

Refugee - Someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war, or violence. A refugee has a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group (as defined by the UNHCR).1

Protracted refugee situation - A refugee situation in which 25,000 or more refugees from the same nationality have been in exile for five or more years in a given asylum country.2

Integration - The act of bringing people or groups with particular characteristics or needs into equal participation in or membership of a social group or institution.

Repatriation - The return of someone to their own country.3

Post-emergency phase - The phase of receiving refugees into camps when the mortality returns to the base level of the surrounding population and basic needs have been addressed.4

Durable solutions - Three solutions that, according to the UNHCR, will sustainably mitigate the protracted refugee situation in Kenya. The three durable solutions are voluntary repatriation, local integration, and resettlement.5

Acculturation - “Cultural modification of an individual, group, or people by adapting to or borrowing traits from another culture.”6

Non-refoulement - The practice of prohibiting refugees or asylum seekers from returning to a country in which they are liable to be subjected to persecution.7

Xenophobia - “Fear and hatred of strangers or foreigners or of anything that is strange or foreign.”8

Social capital - The networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society, enabling that society to function effectively.9

Naturalization - The admittance of a foreigner to the citizenship of a country.10

Context

In order to be considered a refugee, one must have a “well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group.”11 There were 25.9 million refugees in the world as of 2019,12 and their situations vary depending on which area of the world they are in. As of 2020, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that around 2.6 million refugees stay in refugee camps, which are “temporary facilities built to provide immediate protection and assistance to people who have been forced to flee due to conflict, violence or persecution.”13 These camps are located mostly in Southern Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.14 Africa holds eight of the ten largest refugee camps in the world, with Kenya as the center of the refugee situation. Due to its close proximity to areas of social and political tension, as well as its general geographic centrality, Kenya has become the principal destination for African refugees seeking shelter from conflict in their homeland. While other countries in Africa are also host to refugee camps, such as Tanzania’s Katumba camp of 66,000 or South Sudan’s Yida camp of 70,000, Kenya remains the African hub for refugees, containing four out of the ten largest refugee camps in the world.15 Of the over 491,000 refugees and asylum seekers registered in Kenya as of January 2020, 84% of them live in a refugee camp.16 One such camp is Kakuma camp, which provided relief to over 184,000 refugees in 2015.17 Another Kenyan camp, Dadaab, was reported at the end of March 2020 to be home to approximately 217,000 refugees18—this is nearly 250% its originally planned maximum capacity of 90,000.19

Refugee camps are variant in how they operate; the UNHCR follows consistent general rules and regulations when constructing and running each camp, while also accommodating for conditions that are specific to Kenya. The space that each refugee camp is constructed on is obtained through negotiations between the UN Refugee Agency and the host country, and the location of the camps and the construction of the basic structures within them are all carefully considered in order to provide adequate security to the incoming refugee populations, as well as be accessible by outside aid.20 When setting up the camp, the organization must follow strict regulations such as ensuring that camp size does not fall below 45 square meters per person and that a general drainage system is established that protects the local environment and prevents flooding.21 While in the camp, refugees use electronic food vouchers to obtain food rations.22, 23 However, in Dadaab, refugees often sell their rations in exchange for smuggled goods due to the fact that they are rarely able to obtain the work permits required to hold jobs and integrate into the local economy.24 Refugees in Kakuma have been reported to also sell portions of their rations to obtain more varieties of food.25

In order for refugees to move freely outside of the camp and throughout Kenya, they must first obtain a movement pass. However, experiences in Kakuma have shown that these passes are obtained through unpredictable and changing requirements, and the overall number of movement passes issued to refugees within Kenyan refugee camps is low.26 When asked about their experiences with obtaining a movement pass, refugees in Kakuma said that the passes were supposed to be free but were often withheld due to bias against different nationalities, and some were only given once bribes had been fulfilled.27

Kenya has seen a continuous inflow of refugees from surrounding areas as a result of political and military conflict in regions such as Somalia and South Sudan, beginning in 1992 with the first mass influx that consisted of 300,000 Somali refugees.28 In addition to the consistent flow of refugees,the UNHCR projected that there will be 30,000 new arrivals into Kenya in 2020.29 As of January 2020, over half of the refugees in Kenya originated from Somalia,30 where they fled from famine, drought, and oppressive ruling caused by militarized insurgency.31 Though the inflow of Somali refugees is decreasing, there is very little outflow of refugees from these camps; it is still estimated that Somali individuals spend an average of 30 years in refugee camps globally, with very few returning home.32 South Sudanese refugees comprise nearly 25% of refugees in Kenya,33 a result of Africa's largest refugee crisis.34 Officially founded in 2011, the country of South Sudan experienced a painful start to autonomy with a combination of violence, economic hardships, and the spread of both disease and hunger. Citizens of this country, especially children, are fleeing to Kenya in hopes of finding respite from these hazardous conditions.35

Due to the large number of refugee camps in Kenya and the tense political climate in surrounding areas, there are many protracted refugees in the country. According to the United Nations, a refugee situation is deemed protracted when “at least 25,000 refugees from the same country have been living in exile for more than five consecutive years.”36 As of early 2019, about 78% of all refugees in the world were considered to be in a protracted refugee situation, a total of around 16 million people, which is a 12% increase from 2018.37 On average, individuals living in Kenyan refugee camps are expected to spend 26 years in legal limbo, having no country to officially call home or gain rights of citizenship in.38

This brief will strive to create a deep and concise understanding of protracted V situations within Kenyan refugee camps; however, there is not extensive research or data available on this topic, specifically regarding how this problem is being addressed. To mitigate the gaps within existing research, information from similar refugee situations in other regions will be drawn on and compared or applied to the specific refugee situations within Kenya. While refugees in general are widely-discussed in the academic sphere, there are few studies or data specifically focused on protracted refugee populations. The data cited in this brief is taken from numbers reported from credible international organizations, but the context of the numbers is not completely transparent as there is no raw data to which it can be compared. However, the credibility of the sources supports the use of these numbers and statistics in explanation of the topics at hand. In order to obtain the most credible and realistic view possible of this problem, more measurements must be taken of current trends and practices within the camps and the situations surrounding them.

Contributing Factors

Continued Danger in Homelands

The instability and continued threats in home countries result in the prolonged stay of refugees in Kenyan refugee camps. If a refugee’s home country continues to pose a threat or is incapable of providing a safe environment for the refugee to return to, the practice of non-refoulement prohibits the return of refugees to their countries of origin,39 leaving them to wait in a host country like Kenya until resettlement becomes an option. These threats may come from political conflicts or fear of famine caused by natural disasters, such as the drought in Eastern Africa which in 2011 was cited by 25% of the refugees in the Dadaab camp as their original reason for fleeing.40 While voluntary repatriation is a goal for many individuals in camps, and many refugees express a desire to return to their country of origin, unsafe conditions in refugees’ homelands continue to make this goal difficult to achieve.41

The majority of refugees in Kenya (53.7% as of March 2020) are from Somalia.42 Of 97,533 Somali refugees interviewed in 2013 by the Return Help Desk of the Dadaab refugee camp, about 96,369 reported an intention to return to Somalia.43 However, refugees who fled from Somalia in past years now must remain in the camps as conditions in their country of origin do not allow for a safe return. Violence in Somalia initiated by the militant rebel group Al-Shabab has led to altercations with the Somali government forces, and civilians often become collateral of such hostile encounters. According to the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia, there were 1,154 civilian casualties between January 2019 and November 2019.44 In 2018, Somalia had the highest level of forced child soldier recruitment in the world.45 As refugees within the Kenyan camps continue to hear of these humanitarian crises occurring in their homeland, they are not likely nor able to return home and thus extend their stays in these camps until alternative options are made available to them, thus becoming protracted refugees.

Of all the refugees and asylum seekers in Kenya as of March 2020, 24.7% are South Sudanese,46 meaning that refugee population would necessitate returning to the conflict area of South Sudan. Starting in 2013, South Sudan has seen multiple attempts at reconciliation between government officials and rebel leaders, which have resulted in more hostile tension and the deaths of over 400,000 people.47 While another peace agreement was made in March 2020,48 the past failures of 4 similar agreements and 9 ceasefires49 leave both civilians and worldwide political officials skeptical of long term peace. Many refugees who had fled South Sudan to the camps at the onset of these conflicts are likely now reaching their seventh year without repatriation. These protracted refugees must either decide to wait in hopes of a stable peace to be established, or else turn to other durable solutions.

Anti-Immigration Sentiment

Resettlement rates for refugees within Kenyan camps are very low and the countries in which protracted refugees would resettle have lowered quotas, therefore decreasing the accessibility of resettlement. As resettlement becomes harder to obtain and refugees are not granted permanent status elsewhere, refugees are left to wait and the number of refugees considered to be in a protracted situation grows.

Xenophobia in the Host Country

While refugees hope for resettlement in many situations, less than 1% of refugees around the world are resettled each year.50 The United Nations states that “protracted refugee situations stem from political impasses.”51 While the means of obtaining resettlement approval varies slightly by country, it remains a very rigorous process that requires the intensive involvement of governments, often demanding the collaboration of multiple countries. In order to obtain permission to resettle, refugees must first prove their identity and situation. In the Kenyan refugee camps, a refugee is considered for resettlement only if they demonstrate they cannot integrate or repatriate at the time their case is considered and if they fit into one of the following categories established by the UNHCR: “wom[e]n and girls at risk, legal and/or physical protection needs, survivors of torture and/or violence, medical needs, lack of foreseeable alternative durable solutions, family reunification and children and adolescents at risk.”52

Historically, Kenya has been welcoming to refugees, and refugee law and policy within the country focused on refugee protection, especially in the period between 1963–1991, referred to as the Golden Age.53 However, national sentiment on refugees shifted in the 1990s as inflation and unemployment rates rose, leading citizens to view refugees as competition for their jobs.54 Kenya’s view of refugees then evolved to value national security over refugee protection. With this viewpoint, xenophobia grew and refugees continued to be marginalized in Kenyan society. As Kenyan citizens continue to see the incoming refugees as potential threats to their own security, there is little room for those refugees to find homes within the host country.

Xenophobia in Receiving Countries

Even if a refugee does qualify for resettlement, it is not guaranteed they will be allowed to resettle, and a refugee’s case can be rejected at any and all points of the process.55 Once refugees are granted approval for resettlement, they are expected to wait at least a year before they can move to their new country, and they are accepted only if their situation is compatible with the requirements of the receiving country,56 which are often motivated by increasing xenophobia, particularly in legislation.

These anti-immigration sentiments can be seen in the lowering of refugee admissions in many high-income nations, particularly nations that refugees are looking toward as potential homes. US admittance of refugees dropped from nearly 85,000 in 2016 to just over 22,000 in 2018.57 These numbers depict a staggering change in perspectives toward refugees within the global community. This phenomenon is not limited to just the United States;58 Australia, the third leading country in refugee resettlement, has seen a decrease in the percentage of their migration programs dedicated to accepting resettled refugees, dropping from 5% in 2000 to 3.2% in 2015.59 Canada, who as of 2020 was known as the global leader of refugee resettlement, still resettled roughly 20,000 fewer refugees in 2018 than in 2016.60

In 2019, 4,187 refugees from Kenya were resettled, which represented only 0.85% of all refugees in Kenya.61 There is no data available on the resettlement of specifically protracted refugees in Kenyan camps, but as the levels of resettlement in general decrease, there comes a consequential increase in numbers of refugees who must stay at the camp, which results in protracted situations.

Social Separation

Feelings of isolation imposed on the refugees through official policies, as well as the complex social strata of the camps, hinder refugees’ abilities to reestablish their identity and inhibit their work towards self-sufficiency, leading to protracted situations. While many refugees wait in hopes of resettlement or repatriation, after years of living in a protracted refugee situation refugees become more accustomed to living in their host country and seek simply for an improvement in lifestyle and independence from camp life.62 Local integration is made difficult by the isolation of camps and the rules placed over them, which perpetuates protracted situations in Kenyan camps.63

Kenya’s refugee camps, specifically those of Dadaab and Kakuma, are purposefully built far from local cities or marketplaces.64 This purposeful separation of refugees from other citizens of the country serves to perpetuate the idea of “us” versus “them” and fuels xenophobic sentiments.65 Policies enacted in 2012 pushed urban-dwelling refugees into the refugee camps, further publicizing the government’s support for the separation.66 In 2016, the Kenyan government called to shut down two camps altogether, but was not able to do so when faced with opposition from international rights groups.67 Refugees living in these camps subsequently faced social alienation. Though Kenya does have an established plan to allow for naturalization of refugees, the process is rarely put into practice and does not present a realistic option for the refugees seeking a new future.68 With this social separation, refugees are not given the opportunity to grow a network or support group that can help them gain self-sufficiency or establish a new life.

Even within the camps themselves, refugees can often feel isolated amongst the many different ethnic and cultural groups all accumulated into the same living areas. There are nine major nationalities represented in Kenyan refugee camps,69 with many more tribes and clans creating additional subgroups of cultures. For example, the subgroup of Somali Bantu speakers in the Dadaab camp consists of six individual tribes.70 Without shared traditions, backgrounds, or languages, these refugees face even more obstacles when trying to establish a normality within camp life. Many refugees come without family and, as of March 2020, 53.6% of refugees in Kenya were children.71 These demographic groups have no built-in ties of support for them to hold to during this time of transition. Without adequate ability to start anew and without the emotional or social help to do so, refugee situations may become protracted as their attempts to reestablish themselves in society are met with social barriers of language, identity, culture, and beliefs.

Economic Separation

By failing to provide opportunities for the refugees to become economically self-reliant, Kenyan refugee camps perpetuate protracted refugee situations. Refugees within these camps must continue to find economic support from outside parties, rather than building their own self-sufficiency. Without the means to leave the camp or reestablish themselves elsewhere, refugees prolong their stay in the camp, which leads to protracted refugee situations. If these refugees were able to obtain more funds, then they would have a greater power of choice that could separate them from reliance on the camp and create more long-term opportunities.

The UN cites self-reliance as the basis for refugees obtaining durable solutions,72 and economic self-reliance is at the core of this claim. Many refugees in camps are unable to hold a job, and they are subsequently held back by law from creating their own working economy or marketplace. These restraints prevent any indication of permanence.73 However, these laws also create a systemic form of poverty and idleness that does not allow hope for the population of refugees to eventually integrate. Many individuals in Kenya view refugee participation in the economy as being the cause of increased insecurity and decreased economic opportunity and employment.74 Citing security reasons, Kenyan authorities called for restricted movement of refugees in and out of the camps.75 This restricted movement and anti-refugee sentiment stops much economic integration with local Kenyans, as refugees who leave the camps without authorization face the possibility of 6-month jail time and a fine of 20,000 Kenyan shillings (roughly $200 USD).76 Moreover, it is also illegal for refugees to work in Kenya without a work permit.77 These work permits are not freely given to refugees within the camp, and so refugees who seek work outside of the camp risk their own safety among local citizens, police, and militants.78 No longer under the physical and social protection of the camp, refugees working illegally face the chance of jail time, fines, or physical altercations with rebel groups.

Without the stability needed for refugees to provide for themselves, they become continually reliant on the camp for their basic needs, having no knowledge of when this reliance will come to an end. Though no formal economy is established in Kenyan refugee camps, this does not stop unofficial businesses or economic positions of power from forming. Refugees find work such as raising livestock, shuttling food rations, or smuggling local goods in and out of the camps.79, 80 Even though all of the economic production in the Kenyan camps are unofficial, they are accredited with an annual turnover rate of about $25 million USD.81 These numbers validate the idea that refugees are producing members of Kenya’s economy, but a lack of work permits and recognized citizenship leave them with few claims to economic rights or opportunities. While many refugees do find work in the camps, only 2.9% of refugees within the Kakuma refugee camp obtain an income that is above Kenya’s monthly minimum wage of 10,000 Kenyan shillings (about $93 USD).82 When studying the socioeconomic vulnerability of the Kakuma refugees, it was found that only 4.2% of households would be able to sustain themselves without any outside assistance provided from remittances or aid.83 As more refugees enter Kenyan camps and the rules for refugee economics in Kenya continue to prevent their economic growth or integration, the number of protracted refugee situations will be unable to decrease.

Consequences

Inadequate Resources

With more refugees coming in and very few leaving, protracted refugees require resources that must be provided by outside sources for an extended period of time. Refugee camps demand a significant amount of money to maintain, and protracted refugee situations increase the long-term demand for resources.84 Camps are expected to supply enough food, water, shelter, healthcare, and clothes for all of the people under their care. The money needed to supply these necessities often comes from donors, typically national governments who partner with the UN Refugee Agency.85 However, with the increase in protracted refugee populations worldwide,86 there is still not enough aid to adequately support all the camps even with donations.87 Host countries are left to acquire the funding needed to support the refugee camps. The parties responsible for refugee support and protection do not have clearly defined duties, which leads to refugees not being seen as a priority to many governments, especially when their own citizens need to be considered.88 While much is provided by international aid groups like the UNHCR, great financial and social investments are required of host countries.89

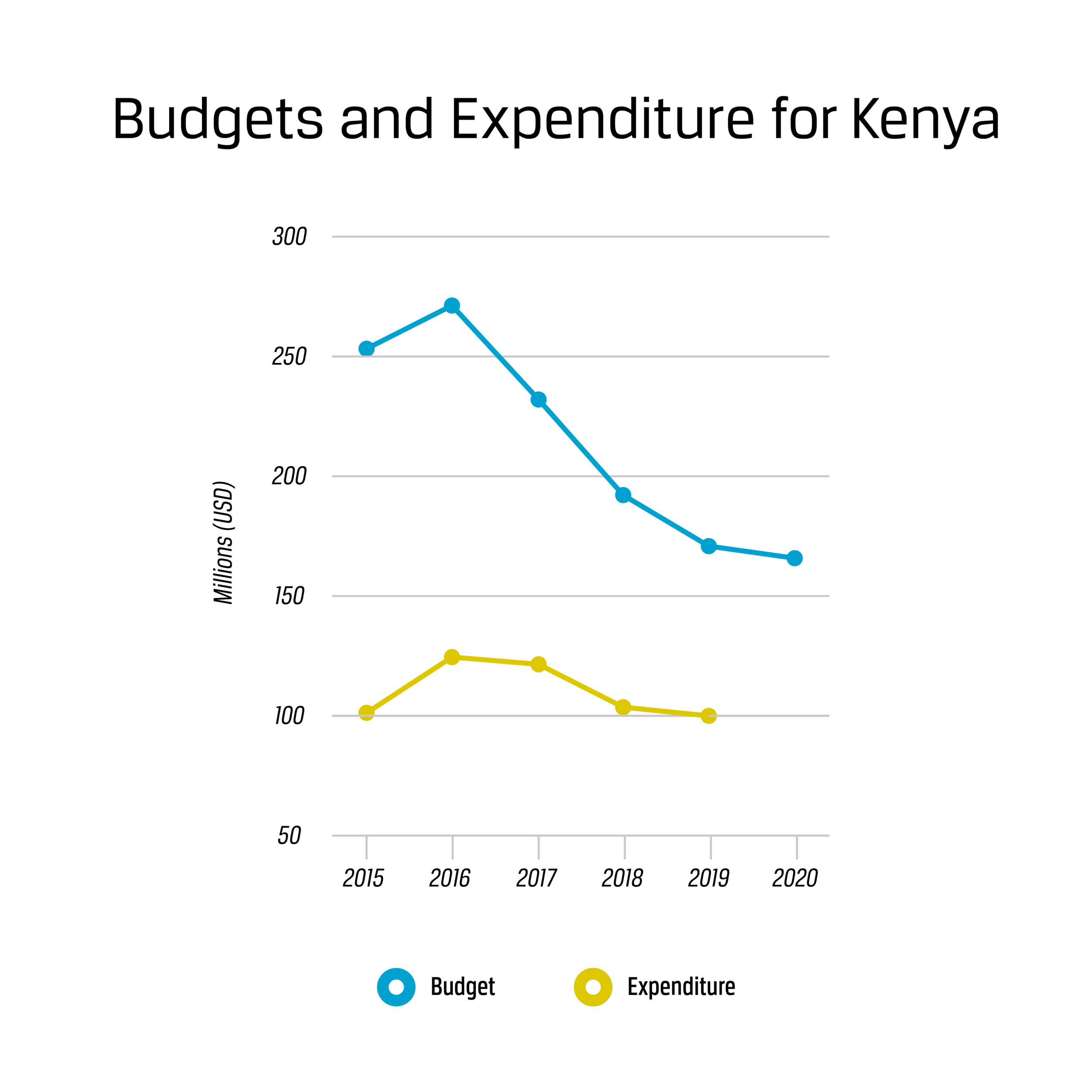

Kenya is a lower-middle income country with limited resources to allocate to the camps90 and must therefore rely predominantly on donations. However, when refugee situations become prolonged, outside donations often slow as international attention in the media decreases. In 2016 the UNHCR budgeted to spend $269 million USD on refugee relief within Kenya,91 but the 2020 budget now shows UNHCR’s planned annual spending on Kenyan refugees to have dropped to $153 million USD.92 It must also be acknowledged that while UNHCR has previously budgeted more for refugees in Kenya, the actual expenditure of such funds has been lower, with confirmed spending in 2016 being $124 million USD, only 46% of the originally planned amount.93 This variance between budget and expenditure likely reflects lack of funding rather than purposeful negligence of unmet needs.94 The UNHCR views protracted refugee situations as a top financial priority, but are themselves struggling to obtain the needed funds. Protracted Somali refugees, for instance, who make up a significant portion of Kenyan camps’ populations, were projected to need $522 million USD in 2018, but only obtained 37% of the needed funds as of September 2018.95

Protracted refugee populations in Kenya use resources that are already limited. If more refugees are entering the camp at a greater rate than are leaving, the refugees already in protracted situations will be faced with a decrease in standard of living and will be exposed to new obstacles, like disease and malnourishment, that will further perpetuate their inability to reestablish a new life. Existing cases of flooding, disease outbreak, and chronic illnesses increase when additional support does not accompany increased inflow of new refugees,96 and this is evidenced by the 11 disease epidemics reported in Dadaab in 2012 following funding shortages.97 This loss in resources creates a cyclical environment wherein protracted refugee populations can increase but not easily diminish.

Vulnerability

Exploitation

Due to the protracted refugees’ extended lack of connection to any specific place, they do not hold all legal protections that a citizen would, which makes them vulnerable to exploitation. Though the Human Rights Committee has sought to gain rights for “non-citizens,” the lack of policy implementation by governments has left refugees with unequal and fewer rights or recognition of rights in comparison to the other members of their host countries.98 The aforementioned policy restricting refugees from working in Kenya leads many to be economically vulnerable. Refugees often turn to other forms of income,99 making individuals vulnerable to sex trafficking and exploitation.100 Such exploitation was uncovered in 2002 in Sierra Leone and Liberia where interviews with refugees revealed that women and girls were bartering sexual acts in exchange for food and other commodities.101 Though the exact number of women and girls who admitted to comitting sexual acts is not specified, the interviews conducted eventually led to allegations of sexual misconduct against 67 different victims.102 While the UNHCR has since implemented gender-sensitive programs and added guidelines to halt any additional harm,103 there continue to be reports of women and girls in Kenyan camps who use sex as a mechanism for survival.104 Specifically in protracted refugee situations, refugees are presented with increased and prolonged hostility and limitations on rights that increase their odds of being caught up in exploitation.105, 106

After years of waiting for resettlement or other means of starting a life outside of the camp, many refugees can become desperate, and there have been many reports of aid workers accepting or even demanding bribes in order to secure refugees the resettlement approval that they have been waiting for.107 Somali refugees in the Dadaab camp reported the cost of resettling a large family to be almost $50,000 USD.108 In the Kenyan camp of Kakuma, refugees have been known to sell their shelters in order to obtain the funds necessary to satisfy bribes for resettlement.109 Much of this exploitation happens within internationally organized aid groups like the UNHCR,110 but there are measures being taken to lessen the extent and prevalence of these actions.111

Lack of Opportunity

Refugees in protracted situations also face vulnerable futures due to lack of opportunities available to them, whether in the economic, educational, political, or social sphere. Lack of opportunities leave protracted refugees’ futures unguarded and unknown. There is a positive correlation between education and quality of life112 and, therefore, a lack of education closes many potential opportunities in one’s future. Minors make up 54% of the camps’ populations,113 yet “almost half of school-age refugees are still out of school.”114 With no means of securing a future through education or economic improvements, protracted refugees face a loss of social capital. Social capital is built through strong social ties and a sense of belonging,115 both of which are hard to find for refugees who have been uprooted from their homes and have now had to live surrounded by many different ethnicities and cultures. It has been found that migrants with greater social capital have a greater chance of obtaining work, but this is far less applicable in the context of refugee camps, as there is no formal social or economic structure to integrate into.116 The UNHCR highlights the loss of human capital in these camps by saying:

“If it is true that camps save lives in the emergency phase, it is also true that, as the years go by, they progressively waste these same lives. A refugee may be able to receive assistance, but is prevented from enjoying those rights—for example, to freedom of movement, employment, and in some cases, education—that would enable him or her to become a productive member of a society.”117

Mental Health Issues

Protracted refugee situations expose refugees to extended periods of physical and emotional duress that is detrimental to their mental health. Repeated trauma and a lack of an established home has led to mental illness, specifically depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Long-term holdings in detention centers, similar to refugee camps, have produced insightful statistics, bringing to light that adults exhibit a threefold and children a tenfold increase in psychiatric disorders following detention.118 A study conducted in a Lebanon refugee camp found that roughly 29% of adults in a protracted refugee situation had at least one mental disorder.119 While there are no studies specifically about the mental health of protracted refugees in Kenya, there is reason to believe that similar results would be found in Kenyan camps, as the refugees in Dadaab have been classified by the Center for Victims of Torture as having “severe” reported levels of trauma and torture.120 In 2017, 4,500 of the estimated 239,400 refugees in Dadaab had been diagnosed with some sort of mental condition.121 However, this number is based on Western diagnostic tests that have differing criteria and do not include those who have not been diagnosed, making it reasonable to infer that the existing number of refugees with a mental health condition is much higher.122 Various large-scale studies on refugee mental health worldwide estimate that approximately 5% of refugees have depression and 9% of refugees suffer from PTSD;123 the percentage of refugees with PTSD can reach up to 40% depending on their history of compounding trauma.124 Of all the mental health disorders found in refugee camps specifically, PTSD was the most prevalent. In fact, 38.6% of patients from 1997–1999 within the Kakuma refugee camp were diagnosed with the condition.125

Refugees, by definition, have all faced some acute level of mental duress. Even after arriving in these camps, the post-emergency phase of care creates new circumstances where anxiety and trauma can arise.126 Previous research on asylum seekers kept in long-term detention and with refugees that had experienced persistent trauma found that the rates of mental illness were significantly increased.127 Due to poor conditions in the camps and the stress that the lifestyle of uncertainty brings, protracted refugees’ trauma is compounded and perpetuated. In a meta-analysis of refugees, individuals were found to be “vulnerable to multiple dimensions of psychopathology beyond those that are narrowly posttraumatic.”128 Once these mental health conditions are diagnosed, both the refugees and the medical personnel assisting them must still overcome the cultural, physical, and linguistic barriers that stand between the refugee and proper treatment.129 There have been numerous instances where refugees have not been able to receive the care they need due to a language barrier,130 and many mental illnesses are viewed as taboo in some of the origin cultures of refugees in Kenyan camps.131, 132 Because of this, current treatment strategies often fall short of addressing the problems held within the unique cultures and demographics, and more studies must be done to improve the treatment administered to these clients.133

Social Insecurity

Protracted refugee situations lead to loss of social stability and identity, as well as an increase in physical violence due to social imbalance. When refugees are displaced to refugee camps, there is a disruption in both family bonds and in self-identity.134 With constant policy changes and hopes of resettlement, their futures are unknown and do not allow for planning.135 Because refugee camps are never intended to be permanent, even the people in charge of the camps cannot say with certainty what will become of protracted refugees. Living long-term in a refugee camp means fundamental and consistent changes to everyday life. Due to the instability of their situations and their separation from others in Kenya, refugees struggle to find what role they can take on in the social environment of the camp.136 Forced migration demands that aspects of the refugees’ home culture and lifestyle must be left behind, a phenomenon exacerbated in protracted situations that further distance the refugees from their past customs and identities.137 As protracted refugees are surrounded by other cultures and groups, acculturation is likely when the refugees attempt to reestablish a new identity amongst their new environment.138 In a study on this psychosocial process, refugees were found to often lose their native language in favor of the majority, which contributes to refugees reporting feelings of grief and anger over the loss of their past lives.139

With so many different cultural, ethnic, religious, and social backgrounds converging in one place, violence in the form of rape, assault, or general hostility has been reported within the Kenyan camps.140 Even before the recent migration waves that have taken place, the Dadaab camp in Kenya was reporting a rise in unrest amongst the refugees.141 Similar camps in Jordan have reported complaints from refugees concerning other refugee sup-groups on the basis of past socio-economic habits, on-going ethnic traditions, etc.142 Refugees that have lived so long with these tense conditions that they must choose to homogenize with others or else continue in this social unease.143 Even after such integration into camp life, opportunities to feel connected to the society of the host country are rare, and some refugees explained they felt trapped due to the imposed separation of the camp.144 This constant separation and stagnation means that protracted refugees are sustained in a limbo state.

Practices

Each practice outlined below directly correlates to each of the UNHCR’s stated durable solutions. There are three durable solutions supported by the UNHCR: voluntary repatriation, resettlement, and local integration.145 The solution favored most by the UNHCR is voluntary repatriation, as this allows refugees to return to their lives in their homeland.146 However, if repatriation is not available to the refugees, they can seek out resettlement options. Resettlement involves relocation to a third country that has agreed to admit the refugee under refugee status. Resettlement often involves long legal processes, and only about 1% of refugees are resettled every year.147 Local integration is the third durable solution available to refugees and is achieved through naturalization. Integration is most often seen in refugee populations living in cities in the host country rather than in camps.The encampment policy in Kenya severely limits refugees’ ability to integrate as most refugees in Kenya (84%) live in refugee camps and are physically separated from cities.148

Durable Solutions

Establishing Peace in Home Countries

Refugees cannot participate in voluntary repatriation until their homelands present a viable future that does not consist of fear of persecution. In order to make repatriation an option for these refugees, the countries where the refugees have fled from must become stable. For refugees in Kenyan camps, this focus is on South Sudan and other neighboring countries, such as Somalia. Not only does establishing peace in these countries allow opportunities for protracted refugees to return home,149 but it also prevents current civilians from having to flee, thus stopping the formation of new protracted situations.

The United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS) is dedicated to establishing and promoting peace in the young nation of South Sudan, which is a major contributor of refugees for the Kenyan camps. UNMISS is a branch of United Nations Peacekeeping which deploys troops and police to areas of conflict in order to help maintain a stable atmosphere in which reconstruction can take place.150 Their mandate is centered on civilian protection and human rights monitoring, as well as implementing and supporting cessation of hostility agreements.151 UNMISS works to secure protection sites for South Sudan’s most vulnerable populations, while also patrolling areas of conflict.

Impact

As of March 2020, UNMISS reported having 13,795 uniformed troops in South Sudan dedicated to curbing tension and protecting citizens.152 With $1.18 billion in funding,153 UNMISS focuses on largely militarized endeavours with the goal of isolating and controlling tense population areas. There are few numbers published by the organization about their impact in South Sudan, but other sources give insights into the help that they are giving. According to one study conducted by Effectiveness of Peace Operations Network on the impact of this organization, UNMISS provided physical protection to over 200,000 South Sudanese civilians between 2013 and 2016 and is accredited by many to have saved tens of thousands of lives amidst violent conflict;154 many South Sudanese have stated that the involvement of UNMISS helped to prevent a genocide from occuring.155 While UNMISS has primarily been focused on civilian protection ever since civil war broke out in South Sudan in 2013, they must now find a balance between aiding the government in rebuilding, while also not enabling any hostile behavior of those in power.

Gaps

While UNMISS does help establish peace in the homeland of many refugees’, they do not help rebuild the country past a base level of stabilization. This could be a factor of concern, but it must also be acknowledged that once UNMISS resolves the tensions causing civilians to flee, other organizations such as the American Relief Agency of the Horn of Africa (ARAHA) are able to then bring aid and help assist where UNMISS does not.156 Additionally, because the stabilization of refugees’ homelands is such a big undertaking with countless variables involved, it is hard to measure the impact that each specific program is making. Even once such aspects can be measured, not much is currently being done to uncover if this method is truly influencing the decisions refugees make on whether to return home. Before causality can be determined, more analysis and data collecting needs to be done by UNMISS.157

Local Integration

One of the durable solutions favored by the UNHCR is local integration. There are three parts of integration: social, economic, and legal. Social integration comes through community connection and networking, something that is possible informally but is difficult for the refugees to achieve in person when they have very little freedom of movement in Kenya. Economic integration of refugees in Kenya happens frequently and informally as goods are smuggled in and out of the camp and as refugees are hired for odd jobs by those in Kenyan cities. Legal integration, as opposed to the other parts of integration, occurs only formally when refugees are granted citizenship in their host country. Within the past decade, it is estimated that only 1.1 million refugees gained citizenship in their country of asylum.158 Though the ability to achieve citizenship is not the only marker of adequate integration of refugees into a host country, these low numbers are a quantitative indication of the troubles many refugees have integrating and being welcomed into a host country. By increasing positive relationships between refugees and the community, as well as decreasing the negative policies placed against refugees, refugees are better able to become integrated into society, thus escaping protracted situations in camps.

One organization that is focused on improving this option for refugees is the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) in Kenya.159 HIAS previously focused on Hebrew immigrants specifically but has now expanded its focus and become an international organization with branches worldwide, focused on gaining social and economic inclusion and freedom for refugees.160 The Kenyan branch seeks to help the most at-risk refugee populations through a community-based approach.161 The mission of this organization is to improve living conditions and decrease prejudice by educating refugees on their rights as well as providing programs for more marginalized groups, such as any LGBTQ refugees or victims of gender-based violence.162 HIAS helps increase refugee presence and focus within local policy and partners with local NGOs to help refugees have adequate social and financial support upon entering the community.163 By offering services such as gender-based violence prevention to local communities alongside the refugees, HIAS improves relations between Kenyans and the refugees within the country.164 This organization also seeks to increase local economic opportunities available to refugees by encouraging entrepreneurship.165

Impact

While HIAS in Kenya does help with the local integration of refugees, the only definitive number they report is the number of people in Kenya that they reach, which is between 1,000 and 1,400 people each month. However, specifics of their classifications of outputs are not present.166 This lack of data does not diminish the importance of their work, but more information needs to be collected on how their services are changing the refugees’ lives. HIAS addresses each aspect of integration through their different programs, and their reported solutions answer challenges that directly face protracted refugees. The path to full integration does exist for refugees in Kenya,167 and HIAS has implemented initiatives that help refugees obtain all the rights available to them through a mix of education about the legal system and empowerment. With help along the route to local integration, protracted refugees have greater odds of establishing a life outside of the camps.

Gaps

Because so little data is available on the subject of integration initiatives, it is impossible to know what kind of services are lacking in these programs. In order to address the real issue of refugee integration, measurements of current practices must be taken. This will provide a benchmark whereupon organizations can improve and best help protracted refugees. Alternate international organizations are helping with integration, but they do this by integrating the refugees into their communities after they are resettled rather than promoting resettlement itself.168

Additionally, there are constraints to the data collection methods used. Integration is difficult to quantify because much of the social and economic integration takes place informally and over long periods of time. However, since full local integration is obtained only after gaining citizenship, data on the naturalization of refugees in Kenya can provide a way by which the refugee experience can be tracked. These public citizenship and naturalization records are not easily found on any of the Kenyan government’s public sites, which could make data tracking and collection difficult. Protracted refugees are not commonly specified in the collection of data either, which further lessens the ability to draw causal relationships between HIAS and protracted situations in Kenya.

Legislation Change

All of the durable solutions described by the UNHCR involve complicated official processes that often prove to be difficult to access for the refugees in protracted situations. Increased advocacy in the political sphere can help change the policies that are curbing progress for the refugees, and increased professional help getting through the necessary judicial processes can help increase the chances of resettlement or citizenship for refugees.

Refugees International (RI) is an organization that is focused on increasing global concern about displacement crises by investigating and reporting the issues, creating policies, and advocating for change.169 While RI works closely with governments and the UN, the organization does not accept funding from these sources in order to ensure that no bias is involved in the reporting or creation of solutions.170 While this organization works all across the globe, they have published many reports on Kenya and the conditions of the refugees in the camps.171 Refugees International has programs dedicated to covering global issues that are largely underreported on, such as climate displacement or displacement brought about due to COVID-19.172

Impact

Though there are no concrete numbers available as to how many people have been affected by RI, their reports have been influential to policy implementation and global awareness. Their impact was seen in 2018 following their advocacy after the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar.173 Following their reports, the UN Human Rights Council and the U.S. Department of State both began more extensive investigations and interferences. Similar cascading events took place regarding crises in Ethiopia, Turkey, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.174 So, while quantitative and causal data is not available, qualitative and correlative data suggests that RI’s reporting holds power in the global community.

Gaps

While RI does influence general sentiment on the issue, there is very little data concerning whether or not their reporting and policy advocacy play any role into how legislation is passed or changed. Also, even once legislation changes to be more inclusive of refugees, RI does not have a program established to help refugees in the resettlement process. The work done by RI is not specifically targeted to help refugees return home, so it is unknown how many refugees can credit this organization for their newfound resettlement. Qualitative data from interviews with refugees or policymakers would help better establish to what extent RI is helping change legislation and help refugees gain resettlement.

Preferred Citation: Utsch, Lorin. “Protracted Refugee Situations in Kenyan Refugee Camps.” Ballard Brief. August 2020. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints