Struggle for Hawaiian Cultural Survival

By Emma Kauana Osorio

Published Winter 2021

Special thanks to Lorin Utsch for editing and research contributions

+ Summary

Hawaii is known around the world as a paradise—an ideal location for exotic vacations in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. However, before 1778, it was a hierarchical, independent nation full of indigenous, self-sufficient, Native Hawaiians that dwelled in harmony with their families, their islands, and their culture. From the arrival of foreigners on the Hawaiian islands up until the present day, the Native Hawaiian culture and population has been largely suppressed and has struggled to survive, nearly becoming extinct. This is due to the integration of Western influences through missionary work, the spread of foreign diseases, the introduction of a capitalist economy, and the illegal annexation of Hawaii by the United States Government in 1898. Because of this, the native language has been almost completely lost, the native population has shrunk and has suffered higher rates of illness, poverty, and homelessness, and Hawaiians have had to constantly fight for the sovereignty of their culture. However, cultural revival is currently underway from a recent resurrection of Hawaii’s preservation and celebration of traditional practices.

+ Key Takeaways

+ Key Terms

Ali’i - The highest social class in Hawaii, composed of the highest ranking chiefs and royalty that ruled over their respective islands or portions of islands.1

Konohiki - A subset of chiefs or landlords who served under the ali’i class.2

Kamehameha I - First king of the Kingdom of Hawaii who united all of the islands into one island kingdom with the help of European weapons and military expertise.3

Queen Liliuokalani - The last monarchical ruler of Hawaii until she was dethroned by the U.S. government in 1893.4

Kuleana Act - The Kuleana Act established a legal system of land ownership, gave Native Hawaiians claim to the land they lived on and legalized the purchase of those lands by foreigners. The passing of this act caused many Hawaiians to lose their homes which has led to the massive amount of homeless Native Hawaiians in Hawaii today.5

Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) - A public agency with the responsibility of improving the well-being of Native Hawaiians.6

Context

Q: What is the value of culture to Native Hawaiians?

A: George S. Kanahele, a Hawaiian activist and historian, once said, “For Hawaiians, a person’s identity is inseparable from place, particularly their ancestral homelands.”7 To many Hawaiian natives, their identity is their culture. As an example of the importance of Native Hawaiian culture, one of the top priorities of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) is to raise the appreciation and value of Native Hawaiian history and culture to 85% by residents of Hawaii.8 Not only does the government of Hawaii support the importance of Hawaii’s culture, but so does their educational system. Hawaii’s largest private schools, Kamehameha Schools, admit only Native Hawaiian students with the mission to “improve the capability and well-being of Hawaiians through education” and “ground them in Hawaiian values.”9 This brief will discuss the history of Native Hawaiians, which is necessary to understand the importance of Hawaiian culture and why Hawaiians are so devoted to keep their culture alive.

Aloha Aina Unity march in Hawaii

Copyright credit: Cory Lum/Civil Beat

Q: What is currently happening to Hawaiian culture?

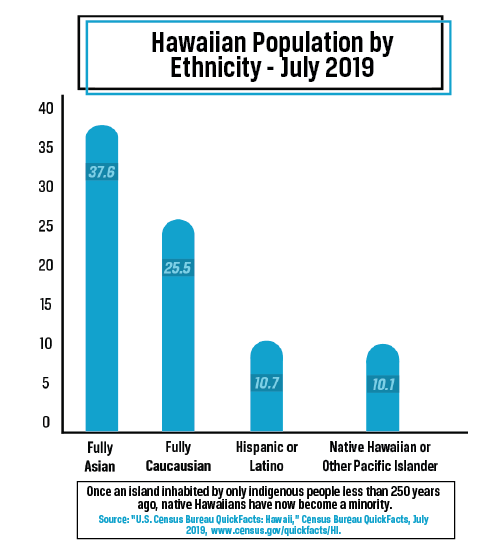

A: The culture of Native Hawaii has experienced a dramatic decline since its discovery by Western explorers. This shift in Hawaiian culture has occurred as the demographics of the Hawaiian ancestral land has changed, which has led to a loss of identity and culture for Native Hawaiians. The majority of cultural practices that were once common for every Native Hawaiian (sea navigation, fishing, family dynamics, land usage, and religious musical expression such as hula, chanting, singing, etc.) have been overcome by Western influence. Despite the Hawaiian cultural renaissance of the 1970s that brought many of these cultural practices out of the shadows, Hawaiian culture is still dwarfed by Western influence. This struggle for Hawaiian cultural survival affects Native Hawaiians today in social, physical and emotional ways.10

History: Original Inhabitants of Hawaii

According to linguistic evidence, the original settlers of Polynesia were the descendants of the Lapita people11 who originated from Taiwan close to 3,000 years ago (1000 B.C.E).12 Due to shared similarities found between all Polynesian cultures and languages, it has been theorized that these people first arrived in eastern Polynesia13 and then voyaged from island to island by canoe frequently in search of new land,14 interaction, exchange of goods and culture.15 The sea voyagers traveled distances as far as Chile.16 Historians believe that this group migrated across greater distances of ocean than any other cultural group in history.17

Hawaii was found and inhabited in 400 C.E. by people from the Marquesas Islands, 2,000 miles away, who were traveling in large canoes.18 These settlers then began to prosper on the islands under a chiefdom. Their faith in Hawaiian mythological gods inspired them to achieve highly developed agricultural and aquacultural systems, advanced celestial navigation and seafaring technology, and architecture. Their clothing and ceremonial practices accompanied by the ancient hula, music, and poetry are other distinct characteristics of this culture.19

An Offering before Captain Cook in the Sandwich Islands

History: European Colonization

In 1778, Captain James Cook of England accidentally landed on the shores of Kauai and was the first foreign entity to make contact with the islands.20 The local Hawaiians considered Captain Cook to be a god, and as such the Englishmen were welcomed onto the island.21 Natives were introduced by Captain Cook’s men to material goods they had never seen before, such as firearms, the compass, knives, and others. The Englishmen also brought foreign diseases, like smallpox, that decimated the islands’ population.22

Statue of Queen Liliʻuokalani

In 1810, Kamehameha the Great united the islands under one nation, the Kingdom of Hawaii, with Western help in the form of military counsel and firearms.23 Though Hawaii was known to be an independent monarchy, colonizing nations such as England, France, and the United States soon started to deploy warships and assign government officials to obtain control and create a “civilized” nation, which, to these Western powers, defined true sovereignty.24 Outsiders, including traders, planters, labor recruiters, guano miners, settlers, missionaries, and government officials, incorporated the islands into the global economy to help increase funds for colonizing powers.25 As the reign of the Kamehameha dynasty continued to intertwine with Western education and ideals, foreign nations knew that it was only a matter of time before they could claim Hawaii. As Hawaii was a prime location for merchant ships to pass through and port their boats, the island began to provide resources to visitors. As early as the 1820s, the ali’i interacted with merchants, looking for loans and consumer goods in order to maintain their status as royalty.26

As the complex relationship of shared power between European and American nations within Hawaii continued, their citizens began to integrate themselves into Hawaiian society as missionaries, government advisors to the King, and businessmen in the new capital of Honolulu.27 Sugar and pineapple plantations were primarily run by American businessmen, which gave large influence to America as a colonizing power. Eventually, these American businessmen would follow presidential orders to overthrow the last member of Hawaiian royalty, Queen Liliuokalani, in 1893. The dethroning of Liliuokalani led to the final annexation of the Kingdom of Hawaii into the United States of America in 1898.28

Contributing Factors

Westernization

Western influence, brought upon by the colonization of a foreign land by a Western nation, is harmful to native cultures. This can be seen in many indigenous groups all around the world such as Native Americans, Aboriginals of Australia, and in this case, Native Hawaiians. In many historical instances, Western nations colonize an area and subsequently impose their own culture onto the native population, discouraging or even eradicating native cultural practices.29 This is known as cultural imperialism, and its effects are far-reaching.

When foreign missionaries, specifically American Protestant missionaries, arrived in Hawaii in the 1820s, they used their strong influence over the ali’i and village people to promote their religious and Western ideals over native belief and culture. Though the missionaries intended to help them remain a sovereign nation, their close bond with the locals inevitably gave the American government leeway towards annexation.30 Though missionaries did help preserve the Hawaiian culture in some ways, their influence was detrimental to many foundational Hawaiian practices.31 32 For example, claiming the hula promoted “lasciviousness,” many prominent US missionaries were committed to its abolishment.33 In 1830, the dance was eradicated by Ka’ahumanu, wife of Kamehameha I, after she converted to Christianity and was convinced by missionaries to deem hula unlawful.34 Once a deeply religious and important cultural tradition, hula dancing became discouraged until 1886 when King Kalakaua, a firm believer in hula revival, was crowned. He appointed hula performers to take part in his coronation.35

Westernization continued to negatively influence Native Hawaiian culture in the 1900s through perverse depictions of a carefree “white man’s paradise” through postcards, films, and other types of media.36 Portrayals of dark-skinned women who were waiting for the “embrace” of Caucasian men created the notion that Native Hawaiian women were naturally submissive and happy to receive foreigners into their lands.37 On the other hand, native leaders of Hawaii were portrayed in the media as savage and uncivilized to promote the idea that they were unfit to lead a nation and required Western colonization.38

The misrepresentation in the media of Native Hawaiians and their culture has twisted the world’s perspective of these people, and it may never change. In a recent report done on Native Hawaiians and tourism, researchers acknowledge the “uneasy” relationship between Native Hawaiians and “the mainstream of Hawaii’s political and economic institutions,” as “many Native Hawaiians feel the [tourism] industry’s growth has contributed to a degradation of their cultural values.”39 As a result, Hawaiians struggle with an authentic representation for themselves and their culture.

Despite efforts for complete revival, true hula remained hidden and has become instead subverted by the media (e.g. coconut bras and grass skirts) as it still holds this reputation to this day. As years have gone by, the media and large influence of tourism on the islands have also increased the effects of Westernization, especially on the hula. Clara Bow, a famous actress in the 1920s, released a silent film called Hula where she sports a grass skirt, a flower lei, and a coconut bra—items of clothing that ancient Hawaiian hula dancers never wore.

Footnotes: A, B

Shown here is a picture of Queen Liliʻuokalani, chained to her throne, being carried away from her palace by the bayonets of American soldiers. She is sketched in such a way that suggests she is savage and incapable of keeping Hawaii free from foreign control.

Footnote: C

Introduction of Foreign Disease

The arrival of European foreigners to the Hawaiian islands had a fatal effect on the indigenous inhabitants of Hawaii and their culture when Europeans first arrived in 1778. Diseases spread, threatening the health of almost every single Hawaiian. Smallpox, measles, and whooping cough decimated the native population to the point that by 1890, the total population had been reduced to 10% of what it was before European contact, around 300,000–700,000 people.40 Due to the island’s isolation from the rest of the world, natives of Hawaii had remained unexposed to diseases that the rest of the world had been contracting for centuries. Therefore, when interaction with the outside world began, natives were not prepared to take necessary safety precautions against these diseases. In 1803, an epidemic of a disease similar to yellow fever resulted in approximately 175,000 deaths, and another spread of the measles and whooping cough in 1848 caused the deaths of another quarter of the population.41As more and more people began to die, King Kalakaua was advised to seek out immigrants to work on plantations and help increase the population in 1872.42 For the first time, Hawaii’s native culture suddenly became less dominant as other cultures immigrated into the islands and foreigners weren’t interested in the indigenous peoples’ culture.

Introduction of a Capitalist Economy

Early on in his reign, King Kamehameha I installed the ahupua’a system, a system that divided each island into sections that were designated to different konohiki and families who were trusted to live, farm on, and take care of the land.43 However, Native Hawaiians view land as a past ancestor, not as a property to buy and sell.44 The ahupua’a system worked sufficiently until it was interrupted due to the rapid increase of foreigners who not only wished to visit and work on the islands, but also legally own their own property, as many of them were accustomed to economies with a capitalistic market.45 In 1848, The Mahele Act was then passed which created three distinct groups of legal landowners: the King, the konohiki, and the government of Hawaii; each held “subject to the rights of native tenants.”46

Confusion arose as konohiki began to sell land to foreigners that natives still lived on. In order to more clearly explain the exact meaning of “the rights of native tenants” clause, the Kuleana Act was passed in 1850. This act established a legal system of land ownership, gave Native Hawaiians claim to the land they lived on, and legalized the purchase of those lands by foreigners. The problem that surfaced with the act is that many natives who lived by tradition were unaware that they legally possessed land until they received compensation from its purchase by foreigners.47 After discovering that they had land and that it was being acquired by someone else, they only had 20 days to respond or it would turn into a costly legal battle that many natives couldn’t afford.48 The increase in foreign newcomers and the introduction of Western economic ideals to Hawaii led to the loss of ancestral land with deep cultural ties that Hawaiians have yet to gain back.49

Forced Annexation

The annexation of Hawaii in 1893 would open the door to more permanent foreign control as the door to Hawaiian sovereignty and maintenance of native culture closed. Throughout Hawaii’s relationship with foreign entities, the goal was always to remain independent.50 However, because colonization and ownership of land was highly regarded at that time, Hawaii’s desire to remain independent was not respected by most outside nations. Many countries tried to lay claim to Hawaii using various methods (see Figure 3), but the United States was the nation that ultimately gained political power over the islands.

Figure 3

Though Great Britain, France, and the United States each signed documents that validated Hawaii’s independence, each country’s high taxes on Hawaii, Hawaii’s ever-decreasing population, and the increase of foreign settlers weakened the Hawaiian monarchy.51 Tensions peaked as US citizens living in Hawaii refused to accept a new constitution, created by Queen Liliuokalani, that restricted Americans’ rights to vote in local Hawaiian elections in an effort to give her own people more representation.52 An “Annexation Club” was quickly formed by American businessmen and, despite intense protest by the Hawaiian people and the Queen, United States Minister John L. Stevens and 4 boats full of US Marines overthrew the Hawaiian government. Despite fierce efforts to reclaim their nation, including an anti-annexation petition signed by 38,000 Native Hawaiians,53 Hawaii was officially annexed by President McKinley in 1893.54 Along with the annexation and the American government’s invading influence, Hawaiians lost their independence, furthering the fall of their culture.

Consequences

William Inglis, a visitor to Ka’iulani school in 1907 once wrote, “Out upon the lawn marched the children, two by two, just as precise and orderly as you can find them at home. With the ease that comes of long practice the classes marched and counter marched until all were drawn up in a compact array facing a large American flag that was dancing in the northeast trade-wind forty feet above their heads.

“The little regiment stood fast, arms at sides, shoulders back, chests out, heads up, and every eye fixed upon the red, white, and blue emblem that waved protectingly over them. ‘Salute’ was the principal’s next command. Every right hand was raised, forefinger extended, and the six hundred fourteen fresh, childish voices chanted as one voice: ‘We give our heads and our hearts to God and our Country! One Country! One Language! One Flag!”

Footnote: D

Language Loss

Due to the heavy influence from missionaries and other foreigners, the culture, the language, and many other native practices were discouraged. This caused a near extinction of the Hawaiian language, which began in 1896 after the overthrow of the throne. The Hawaiian language was banned from being taught in schools and was also discouraged from being spoken at home.55 In 1906, the Programme for Patriotic Exercises in the Public Schools began. This program was intended to Americanize the Hawaiian children, and they would be severely punished if they spoke Hawaiian at school.56 Consequently, in 1985, only 32 individuals on the island of Ni’ihau could speak the language fluently, when just a little over 200 years earlier, Hawaiian was the only language known and spoken by Hawaiian natives.57 Hawaiian Pidgin was also created by immigrants on plantations and ranches as early as the 1800s, which altered the Hawaiian language as well.58

In 2001, the College of the Hawaiian Language, the first college of indigenous language, was created at the University of Hawaii at Hilo in efforts to revive the native language.59 In 2016, the Census of Hawaii reported that Hawaiian is spoken at the home by 5.6% of the overall speakers, a total of 18,610 people.60 Though the language has begun a small revival, sustained usage and growth of the language for the future is unknown.

Population and Health Decline

As witnesses to their own nation’s downfall, Native Hawaiians experience traumatic repercussions to their cultural pride, and this trauma is affecting their health today. The Hawaiian population still faces chronic health challenges, largely due to the stress experienced as a result of their perpetual struggle for cultural survival. For example, in 1859, King Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma established Queen’s Hospital, a hospital designated to care for natives suffering from Western diseases, free of charge. However, in 1909, the US government changed the original charter so that Hawaiians had to pay healthcare fees, which many of them couldn’t afford.61

Because of this, along with the fatal effect of foreign antibodies of Western diseases, Hawaiians today suffer the consequences.62 Native Hawaiians are two times more likely than the standard US population to develop Type 2 Diabetes,63 are eight times more likely to die from diabetes compared to non-Hawaiians,64 and five times more likely to die from heart disease compared to non-Hawaiians.65 They also have the second highest mortality rate in the US for all cancers (after male African Americans and female Alaskan natives).66 According to a report by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs in 2017, “Today, Native Hawaiians are perhaps the single racial group with the highest health risk in the State of Hawai‘i. This risk stems from high economic and cultural stress, lifestyle and risk behaviors, and late or lack of access to health care.”67

Perpetuation of Poverty

Due to the effects of the Kuleana Act, Hawaiians have been wrongfully stripped of lands that belong to them, catching them in a poverty cycle because they are unable to access the resources that would allow them to escape poverty. In an attempt to mitigate the consequences of the Kuleana Act, the Hawaiian Homelands Commission Act (HHCA) was signed into law in 1921.68 Its purpose is to “enable Native Hawaiians to return to their lands in order to fully support self-sufficiency for Native Hawaiians and the self-determination of Native Hawaiians in the administration of this Act, and the preservation of the values, traditions and culture of Native Hawaiians.”69 It legally set aside approximately 200,000 acres on several Hawaiian islands for natives who were descendants of the indigenous people that lived on Hawaii before 1778 and are at least 50% Hawaiian.70 However, in 2016, only a little over 6,000 households resided in the Hawaiian homeland and 14,350 were on the waiting list for a lease.71 Of the Native Hawaiian households surveyed in a different report, 12,755 were living on Hawaiian Homestead Land in 2019, though this is still only 11% of the Native Hawaiian population.72

This indicates that many Native Hawaiians are still being deprived of their lands—a vital aspect of their culture, as it connects them to their ancestors—which leads to a perpetuation of their impoverished state. For example, Native Hawaiians make up 42% of the state’s homeless population (7,921 people total), have lower incomes, and have higher rates of poverty.73 And due to higher living costs in Hawaii, Native Hawaiians also face a higher cost burden rate at 40%, surpassing the national rate of 36%, which forces them to “cope with this challenge through extended family-living or overcrowding, taking on additional jobs, or moving to less expensive areas farther from employment.”74 Due to the fact that Native Hawaiians haven’t regained their ancestral land, they continue to face difficulty in accessing housing that would allow them to escape the poverty cycle.

Fight for Sovereignty

The suffering that the native people of Hawaii have experienced is evident. Not only do they experience the highest rates for serious illness, prison incarceration, homelessness, and have the lowest rates of higher education attainment and family income,75 but they also saw their land stolen from them and have watched their culture wither away ever since contact with the Western world took place. Some Hawaiians have grown weary of suffering and have started asking authorities for more rights, including sovereignty.

The Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement began to arise in the 1970s when native farmers nonviolently protested new land development in Kalama Valley, Oahu.76 These protesters held up a sign that said “Kokua Hawaii” (Help Hawaii) and were eventually arrested for trespassing as construction workers bulldozed the land the protestors were trying to protect.77 In the 1980s, protests began to increase as Hawaiians fought for Native Hawaiian autonomy. On January 17, 1993 (the 100th anniversary of Hawaii’s annexation), 15,000 Native Hawaiians marched on ‘Iolani Palace in Honolulu to demand control of the Hawaiian Trust Lands.78 They shouted words like “Ea” (sovereignty), “‘Ike Pono” (see clearly), and “Ka Lahui Hawaii” (the Hawaiian nation) as Honolulu roads closed down and political speeches were given that discussed natives’ options for sovereignty.79

The various sovereignty groups agree that their nation was wrongfully taken from them, but each group is divided by their proposed solutions of reconciliation with America. There are many different activist groups, but the four basic ideas are a State-Within-a-State model, a Nation-Within-a-Nation model, a model of Free Association, and, lastly, complete independence.80 81

Nearly a year after the ‘Iolani Palace March took place in 1993, US President Bill Clinton signed the Apology Resolution, an official document offered to Native Hawaiians in efforts to formally apologize for America’s illegal overthrow of the internationally-recognized kingdom of Hawaii. It expressed America’s “deep regret” for the ensuing “devastation” of the Hawaiian people.82 When this document was released, many Hawaiian sovereignty activists delighted in the fact that an apology was formally offered; however, addressal of sovereignty was not included in the document. Instead, the end of the document simply states, “Nothing in this Joint Resolution is intended to serve as a settlement of any claims against the United States.”83

Today, the Hawaiian sovereignty movement and the fight for Native Hawaiian rights continue. In 2009, Mauna Kea, a dormant volcano and the highest mountain peak in Hawaii, was chosen as the location for the Thirty Meter Telescope, a massive telescope that supposedly could provide 12 times the resolution of images in space produced by the Hubble Space Telescope.84 Hundreds of thousands of Hawaiians have protested the construction of the telescope because Mauna Kea and its summit are considered to be one of the most sacred locations in all of Hawaii.85 In 2019, more than 10,000 Hawaiians joined the Aloha Aina March in Honolulu to protest the Thirty Meter Telescope. Hundreds more camped at the base of Mauna Kea, blocking the only entryway to its summit and impeding further progress of its construction.86 87 In early 2020, news was released that it wouldn’t continue construction until 2021, but natives are still opposed and continue to hope that their voices will be heard and that their culture will be respected.

Practices

Fight for Sovereignty

In the 1970s, a renaissance of Hawaiian culture began. Initiated by Hawaiian musicians such as Gabby Pahunui and “The Sons of Hawaii,” a resurgence of the Hawaiian language, values, and culture was particularly prevalent among Hawaiian youth.88 In 1976, the Hokule’a, a double-hulled canoe designed and constructed in the exact same manner as Hawaiians did hundreds of years before, was rebuilt. It successfully voyaged from Hawaii to Tahiti, more than 2,500 miles, demonstrating ancient Hawaiians’ extraordinary ethnoastronomy and voyaging caliber.89 Hula, once an ancient and forgotten spiritual practice, reemerged because of the annual Merrie Monarch Festival, an international hula competition in Hawaii that hosts hālaus (professional hula dance companies) from around the world to compete for various awards and spread their aloha spirit.90 Now there are hālaus all around the world as Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians alike participate in this ancient Hawaiian tradition.

The Hawaiian language, which was predicted to become extinct by the year 2000, survived because of various efforts from different groups. Larry Kimura and other Hawaiian language activists worked hard to record and radio broadcast the last native speakers in an effort to share and teach it to more natives.91 Punana Leo schools and Hawaiian immersion programs were established to teach the language as well as instill Hawaiian cultural values in Hawaii’s youth.92 Hawaiian became one of Hawaii’s official state languages in 1978 and now The University of Hawaii offers a bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD program in Hawaiian language.93 Though Hawaii has experienced a drastic decrease in the practice and influence of its culture in the past, these efforts for cultural revival are providing renewed hope that practices and customs once discouraged or forbidden can be openly spread and shared.

While this wide dispersal of cultural practices has helped revive Native Hawaiian culture, in order to fully revive Hawaiian tradition and restore natives’ levels of health, financial status, and living conditions, proper policies and legislative measures need to be established. Currently, Hawaii’s state government and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) is working to improve the conditions of Native Hawaiians in the areas of “aina (land), culture, economic sufficiency, education, governance, and health.” However, more direct action must take place in order to disseminate the Hawaiian homestead land awards in a more efficient manner, as well as lower the eligible blood quantum to increase acceptable eligibility for land awards.94 While different organizations are striving to make affordable housing more of a reality in Hawaii, progress is slow and unproductive.95 If Native Hawaiians could regain their “sense of place” with resettlement on their ancestral lands, it is predicted that their quality of life would improve and their culture would flourish.

King Kamehameha III once declared, “Ua mau ke ea o ka aina, i ka pono,” which means “the life of the land is preserved in righteousness,” which later became Hawaii’s state motto.96 While many scholars and historians have interpreted the hidden meaning of this phrase in various ways, George S. Kanahele explained it by saying, “Perhaps the most important thing Hawaiians can do collectively to maintain their sense of place (culture) is to realize that, because our people were here first, we of today have the primary responsibilities for preserving and enriching the life of the land.”97 Hawaiian culture will survive and hopefully continue to thrive because of the combined efforts of the Hawaiian people and other people from distant lands.

Preferred Citation: Osorio, Emma Kauana. “Struggle for Hawaiian Cultural Survival.” Ballard Brief. March 2021. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints