The Harmful Effects of Living in Brick Kiln Communities in the South Asia Region

Image by Bishnu Sarangi from Pixabay

By Cambrie Ball

Published Winter 2024

Special thanks to Mason Scholes for editing and research contributions.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Summary+

Across South Asia, brick kilns pose significant health challenges, socioeconomic disparities, and environmental degradation due to hazardous air quality and exploitative labor practices. The poor infrastructure of kiln sites contributes to dangerous working and living conditions for laborers and their families, which remain unregulated due to the sector’s informal nature. These kilns emit substantial amounts of pollutants, including particulate matter and carbon dioxide, leading to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases and premature deaths. Furthermore, indoor air pollution from burning solid fuels exacerbates health risks, particularly for women and children. Poverty and low wages persist among kiln workers, with many trapped in debt-bonded labor and facing exploitation. Initiatives like GoodWeave and the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) aim to address these issues by promoting transparency in supply chains, modernizing kiln technology, and providing financial support for sustainable practices. While progress has been made in reducing emissions and improving working conditions, challenges remain, including the potential displacement of manual labor by automated technologies and the need for comprehensive social safety nets.

Key Takeaways+

- The South Asia Region (SARThe South Asia Region, comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.17) is the second-largest producer of bricks globally, producing approximately 310 billion bricks annually accounting for 21% of global brick production and significantly contributing to the SAR’s GDP.1

- Informal employment is widespread in the South Asia Region’s (SAR) brick sector, with the majority of brick workers left vulnerable by the lack of social coverage or assistance.2

- Air pollution from brick kilns results in tens of thousands of premature deaths annually in the SAR due to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases developed from working and living in hazardous kiln site conditions.3

- Bull's Trench Kilns, the most common kiln construction in the SAR, emit high levels of hazardous pollutants such as particulate matter and carbon monoxide that harm brick workers’ wellness. Improved designs like Zigzag Kilns can reduce these emissions by up to 80% but can be expensive to implement.4

- Child labor is prevalent in brick kilns across the SAR, with children as young as 5 engaged in hazardous work conditions for long hours, contributing to their vulnerability to physical harm, educational deprivation, and poverty perpetuation.5,6

- GoodWeave International, an organization protecting nearly 1,800 informal laborers around the world,7 has formally improved the standard of 40 kilns in Nepal since 2020 through its Better Brick Nepal initiative.8

- The Climate and Clean Air Coalition’s partnerships have successfully promoted and implemented alternative brick technologies to improve the environmental impacts of brick kilns, but run the risk of harming brick worker job security in the process.9,10

Key Terms+

Brick Kiln—A facility used for the production of bricks through a process of firing clay or other raw materials. Kilns are large, oven-like structures where bricks are fired at high temperatures to harden them. Brick kilns can vary in design and technology, but they generally consist of a firing chamber, where the bricks are stacked and heated, and a chimney to release smoke and gasses produced during the firing process.11

Child Labor—Child labor refers to the employment of children in any form of work that deprives them of their childhood, impedes their ability to attend school regularly, or is harmful to their physical, mental, social, or moral development.12

DALY—Disability Adjusted Life Year. The World Health Organization defines a DALY as representing “the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health.”13

Informal Economy—Unregistered economic activities with market value.14

M10 and PM2.5—Represents particulate matter (PM) that is 10 or 2.5 micrometers in diameter.15

Peri-urban—Transitional zones of land between rural and urban areas.16

SAR—The South Asia Region, comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.17

Subsistence Farming—A form of agriculture in which farmers grow crops or raise livestock to meet the basic needs of their own families or communities, rather than for commercial sale.18

Context

Q: What is a brick kiln community?

A: In this brief, a brick kilnA facility used for the production of bricks through a process of firing clay or other raw materials. Kilns are large, oven-like structures where bricks are fired at high temperatures to harden them. Brick kilns can vary in design and technology, but they generally consist of a firing chamber, where the bricks are stacked and heated, and a chimney to release smoke and gasses produced during the firing process.11 community denotes a settlement or locale where workers and their families dwell in close proximity to brick kilns, characterized by migrant families living in temporary housing, a kiln chimney, brick stacks, and relevant brick production machinery. The South Asia Region (SARThe South Asia Region, comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.17) manufactures 21% of bricks worldwide, second only to China in its production.19 Bricks serve as an ideal building material for several reasons. One of these reasons is the abundance of clay used to make them, which is native to many regions in South Asia. Additionally, their thermal properties, such as their ability to conduct and store heat, are more suitable for releasing heat than retaining it. This quality is particularly welcome in locations with warmer climates, which are typical for the region.20 This production operates seasonally in response to the region’s weather patterns.

Brick-making countries in South Asia see two primary seasons: the wet and rainy (June–September) and the dry season (October–June). Because bricks are made from clay, any unfired and uncovered bricks quickly melt away when hit with precipitation.21 Brick kilns operate primarily during the region’s dry season, creating many migrant workers who live on-site for at least the duration of their seasonal employment. If one were to visit a brick kiln worksite, one would find a community of laborers who live in small, temporary homes within the boundaries of the kiln site.22 Though there are no official definitions or boundaries for what constitutes a brick kiln community, for the purpose of this brief we will define it as the laborers and their families who live within the property bounds of the kilns they are employed by. A brick kiln site typically consists of plots of land bound by rows or stacks of bricks. On the fringes of the kiln site, green (unfired) clay is molded into bricks. Bricks are fired in the kiln chimney, which is surrounded by stacks of red (fired) bricks. Workers’ homes are scattered throughout the site.23 Though laborers in other industries within the SAR are affected by similarly poor conditions due to the nature of their work (such as factory workers who see low wages, unsanitary conditions, and long hours), brick kiln employees are in a unique position where their living conditions and their working conditions are often synonymous.24 This living arrangement means that workers have no escape from the consequences of their poor work environment, perpetuating many of these effects in their own homes for the duration of employment.

Q: Who lives in brick kiln communities?

A: Workers and their families typically live on site: this includes men, women, and children of all ages. Of the nearly 2 billion people that make up the SAR’sThe South Asia Region, comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.17 population, over 16 million of them live and work at kilns around the region.25 While exact male-to-female laborer ratios within kiln communities are not reported, we can expect the proportion to be slightly male-skewed as brick kilnsA facility used for the production of bricks through a process of firing clay or other raw materials. Kilns are large, oven-like structures where bricks are fired at high temperatures to harden them. Brick kilns can vary in design and technology, but they generally consist of a firing chamber, where the bricks are stacked and heated, and a chimney to release smoke and gasses produced during the firing process.11 most commonly employ migrant families (with both husband and wife working for wages) or male migrants.26 Because there is a division of labor within each kiln, it is common for men to perform more skilled labor tasks, such as brick firing, operating animals, and brick stacking, while women most commonly mold the bricks from clay and transport them.27,28

Both bonded and child laborChild labor refers to the employment of children in any form of work that deprives them of their childhood, impedes their ability to attend school regularly, or is harmful to their physical, mental, social, or moral development.12 are prevalent practices at brick kilns.29 Children comprise one-third of India’s brick kiln population, with up to 80% of these children under the age of 14 working 9 hours per day.30 In Nepal, there are an estimated 34,593 children between the ages of 5–17 living on kiln sites, with nearly 52% of them contributing to the kilns’ work. These children make up approximately 10% of Nepal’s kiln workforce.31

Q: When did brick kilns become a substantial factor in South Asia's economic landscape?

A: Bricks have been a prominent construction material in South Asia since as early as 3,000 BC.32 The brick sector has played a prominent role in the SAR’s economic development and urbanization, particularly over the past two decades as the economy has grown at a steady average rate of 6%.33 This growth is the result of and motivation for rapid urbanization, which urbanization has increased the demand for and production of building materials such as bricks. While data for the brick sector's economic contributions to the SARThe South Asia Region, comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.17 as a whole is lacking, Countries, including Bangladesh, Nepal, and India, have measured annual GDP contributions from brick production and sale. Bangladesh’s brick kilns contribute to 1% of the country’s GDP and provide approximately 1 million people with jobs. In Nepal, the construction industry as a whole contributes 11% to their national GDP.34 This increase in economic growth has inevitably led to an increase in urbanization, in which development requires additional construction to supplement the growth.35 In fact, the region’s urban population rose by 10 million between the years 2001–2011 and is expected to grow an additional 250 million by 2030.36 This implies that the need for bricks in the SAR is expected to continuously grow, therefore increasing brick production in the region. Excluding the global decline in child labor in general,37 no studies suggest that kiln conditions have significantly evolved over the course of the brick sector’s existence in the SAR.

Q: Why is this significant in this region?

A: South Asia is a subregion of Asia defined by a series of mountain ranges in the north and the Indo-Gangetic plain to the south. Countries in this region include India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.38 Currently, South Asia’s population sits at approximately 2.03 billion people, making up 25.2% of the global population.39 Brick production is an essential component of many South Asian countries’ economic stability— particularly Nepal, India, and Pakistan.40 Because bricks act as a traditional construction material in most SARThe South Asia Region, comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.17 countries, brick production and laying skills are accessible, familiar, and culturally rooted.41 While Bhutan and Sri Lanka are part of the region, there is a lack of substantial data discussing the brick production industry in their countries. Therefore, they will not be included for the purpose of this brief. The brick-producing countries of the region contribute 21% of the 1.5 trillion bricks globally produced each year.42 However, for the SAR, the majority of these bricks are used domestically rather than exported to outside regions.43,44 It is a popular sector in the SAR because of the rapid urbanization many Asian countries have seen in the past few decades. The brick sector is informal, meaning it is able to function outside of many government employment rules and regulations placed on jobs found in the formal sector.45 Brick production creates jobs for over 16 million people to keep up with the demand for bricks as building materials.46 Brick kilnsA facility used for the production of bricks through a process of firing clay or other raw materials. Kilns are large, oven-like structures where bricks are fired at high temperatures to harden them. Brick kilns can vary in design and technology, but they generally consist of a firing chamber, where the bricks are stacked and heated, and a chimney to release smoke and gasses produced during the firing process.11 are commonly found in peri-urbanTransitional zones of land between rural and urban areas.16 areas of these countries, drawing in laborers from rural towns for low-skill, reliable work and making business in urban areas more accessible for kiln managers and their clients.47

While China stands as the largest producer of bricks globally, accounting for approximately 66.67% of brick production in the world,48 this brief focuses exclusively on the SARThe South Asia Region, comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.17 for the following reasons: Firstly, the lack of credible and comprehensive data and measurements regarding the effects of brick kilns on laborers in China poses a challenge to conducting secondary research on the subject.49 Furthermore, China predominantly utilizes a different kiln chimney model, the Hoffman kiln, whereas countries in the SAR primarily employ Bull’s Trench and Zigzag kilns.50 This divergence in kiln technology and its associated environmental and health effects necessitates a focused examination of the unique dynamics and challenges present within the SAR’s brick sector.

Contributing Factors

Seasonal Migration

The majority of brick kilnA facility used for the production of bricks through a process of firing clay or other raw materials. Kilns are large, oven-like structures where bricks are fired at high temperatures to harden them. Brick kilns can vary in design and technology, but they generally consist of a firing chamber, where the bricks are stacked and heated, and a chimney to release smoke and gasses produced during the firing process.11 workers are seasonal migrants, traveling from their rural homes to work at the kilns. Because these workers engage in regular seasonal migration, cycles of vulnerability and labor exploitation are perpetuated through disruptions to important needs such as employment, education, and access to regular healthcare as their families are routinely uprooted.51

Rural Roots and the Need for Seasonal Work

Rural life in the SAR is characterized by traditional agrarian practices and closely-knit communities, heavily reliant on the agricultural cycle. In fact, 64% of the region's total population is rural and relies on small-scale subsistence farmingA form of agriculture in which farmers grow crops or raise livestock to meet the basic needs of their own families or communities, rather than for commercial sale.18 as a primary source of income.52 However, the economic constraints prevalent in rural areas necessitate seeking seasonal employment opportunities outside the agricultural sector to augment income. In Nepal, a typical rural household brings in over 27,000 Nepalese rupees ($206 USD) per month, averaging about $6 USD per day to support entire families.53 Compared to Nepal’s average cost of living of $1,340 USD per family per month, this rural income is insufficient to meet needs comfortably.54 In Pakistan, this income number falls to about $104 USD per month or $3.30 per day.55 The average monthly income of a rural household in Bangladesh sits at approximately $230 USD.56 The SAR’s predominantly agrarian landscapes, compounded by challenges associated with climatic unpredictability and geographical constraints, curtail year-round earning potential for rural households as weather patterns and access to resources required for certain crops (such as soils and fertilizers) determine the success of a family’s crop yield,57 further determining their food supply to eat and sell.58 Consequently, individuals and families often engage in seasonal migration to urban centers or industrial sectors, such as brick kilns, during periods of heightened demand in order to make ends meet. Brick kilnsA facility used for the production of bricks through a process of firing clay or other raw materials. Kilns are large, oven-like structures where bricks are fired at high temperatures to harden them. Brick kilns can vary in design and technology, but they generally consist of a firing chamber, where the bricks are stacked and heated, and a chimney to release smoke and gasses produced during the firing process.11 are especially suitable for rural families as the seasonal cycles of brick labor align with the seasonal cycles of agriculture. During the dry season, farms experience lower crop yield and brick kilns are in full operation, whereas during the wet season, farms see higher crop yield while brick kilns shut down operations.59 Nepal serves as an example of increased reliance on seasonal labor, as the percentage of households that require secondary income from non-agricultural work has risen from 22% in 1996 to 37.2% in 2011.60 This migration serves as a pragmatic livelihood strategy to address financial constraints resulting from the cyclical nature of agricultural productivity.61

Brick Labor Recruitment

Brick kilns primarily employ workers through a recruiting process. The recruitment process for brick kiln employees involves several key stages designed to meet the labor demands associated with brick production cycles. Labor recruitment begins with local intermediaries or labor contractors who act as conduits between brick kiln owners and potential workers.62 These intermediaries engage in community outreach, often targeting economically vulnerable areas like rural villages, to identify willing laborers. Interested individuals and families express their intent to work during the upcoming brick production season, leading to the negotiation of terms, including wages and duration of employment.63 Once an agreement is reached, workers and their families accept an advance payment and migrate to the kiln site during the appropriate time of year for brick production, which is the dry season. They move into on-site temporary housing and engage in various tasks, such as brick molding and stacking.64 These arrangements are informal, with minimal formal contracts or legal structures governing the recruitment and migration process.65 Thus, labor recruitment and employment in South Asian brick kilns are shaped by local intermediaries and characterized by informal agreements that respond to the seasonal demand for labor in brick production. This aligns with the cyclical financial needs of agriculturally dependent families, causing them to migrate from their rural farms and placing them in the hazardous working conditions of brick kilns.66

The Migration Process

The migration process for recruited brick kiln laborers in South Asia often has both physical and logistical challenges that influence laborers’ safety and quality of life. Once recruited, laborers embark on journeys to brick kilnA facility used for the production of bricks through a process of firing clay or other raw materials. Kilns are large, oven-like structures where bricks are fired at high temperatures to harden them. Brick kilns can vary in design and technology, but they generally consist of a firing chamber, where the bricks are stacked and heated, and a chimney to release smoke and gasses produced during the firing process.11 sites, often located in regions far from their homes, and even to other countries. For example, in Nepal, 46% of brick workers come from India. Thirty-two percent of native Nepalese kiln workers travel from districts within Nepal but outside of the one the kiln is located in, and 22% originate from the same district as the kiln where they are employed.67In the SAR’sThe South Asia Region, comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.17 brick-producing countries, in-country laborers make the bi-annual migration hundreds of miles from their rural homes to the kiln sites, requiring multi-day journeys.68 The migration typically involves a combination of walking, public transportation, and, in some cases, overcrowded vehicles.

These journeys that brick labor creates a need for can be dangerous and cost laboring families a sum of money for travel, perpetuating their economic and health vulnerabilities.69 The migration is not only a geographical shift but also a cultural transition, as workers move from rural to peri-urbanTransitional zones of land between rural and urban areas.16 or urban environments. This transition accompanying their migration exacerbates the sense of displacement and marginalization experienced by brick kiln workers. It redefines their identity as "people out of place," contributing to a sense of social isolation and exclusion from mainstream society.70 Additionally, being perceived as peripheral individuals further compounds their vulnerability to exploitation, separates them from resources and services, and reinforces their precarious living and working conditions within the brick kilns.71

Lack of Policy and Regulations

There is a lack of government policy and regulation in the SAR’sThe South Asia Region, comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.17 brick industry that results in significant impacts on brick kiln conditions, such as lax labor and safety standards. While the brick sector comprises a major portion of SAR’s economy, it remains informal in the region. Informal economies are activities within a country’s collective economy that are not formally registered despite them having market value.72 Measuring people who work informally in these economies entails assessing the workforce engaged in activities that are not officially recognized or regulated by the government. Although this lack of formal recognition often leads to underreporting and challenges in data collection, the World Bank states that three-fourths of all employees in South Asia work informally.73 Despite their substantial contribution to the economy, these informal workers often operate without the protections and benefits afforded to formal employees. This is largely because they do not fall under government jurisdiction, and are therefore not subject to taxation or strict government regulations.74 This lack of regulations often results in loose labor and safety standards in the workplace, despite the industry and employee regulations outlined by each SAR country’s Ministry of Labor and Employment.75,76,77 For example, India’s Ministry of Labor and Employment constitutionally declares safe and healthy working environments as a fundamental human right and denounces hazardous environments, including child and adolescent labor.78 However, with limited monitoring from the government institutions that designed these policies, laborers are subject to unregulated conditions put in place by brick kiln owners and supervisors.79

These kiln conditions include a lack of worker protection, including physical protections such as appropriate worksite safety gear, and social protections such as social security, disability insurance, unemployment, sickness and maternity leaves, old age pensions, health care, and food assistance.80,81 Despite the SAR’s implementation of social protection measures as early as the 1940s, the insufficiency in coverage for informal workers is underscored by the region's low Social Protection Index (SPI) of 0.061, a ratio that reflects the inadequacy of total social protection expenditures relative to the number of potential recipients, with South Asia registering among the lowest scores in Asia.82 The SPI, calculated by dividing total social protection expenditures by potential beneficiaries and comparing it to the GDP, serves as a critical metric revealing the challenges in extending adequate social protection to informal workers in the region.83 In Pakistan alone, 71.1% of all informal laborers (excluding the agricultural sector) are without any form of social coverage or assistance.84 As seen in SAR’s brick sector, this lack of protection and policy regulation can foster negative effects from living and working on kiln sites, including low wages, long hours, and child laborChild labor refers to the employment of children in any form of work that deprives them of their childhood, impedes their ability to attend school regularly, or is harmful to their physical, mental, social, or moral development.12.85

Infrastructure

Poor and insufficient infrastructure of buildings and facilities on kiln sites negatively impacts the health and safety of workers and their families living and working in dangerous conditions. This is because it exposes them to hazards such as inadequate safety measures and sanitation and leads to increased risks of injuries and respiratory illnesses.86

Housing and Facilities

One of the defining characteristics of brick kilnA facility used for the production of bricks through a process of firing clay or other raw materials. Kilns are large, oven-like structures where bricks are fired at high temperatures to harden them. Brick kilns can vary in design and technology, but they generally consist of a firing chamber, where the bricks are stacked and heated, and a chimney to release smoke and gasses produced during the firing process.11 communities is the transient nature of housing associated with the seasonal kiln operation. Workers and their families typically live in makeshift structures constructed from materials readily available, such as clay and straw, fired bricks with no mortar sealing, and tin roofs secured by an assortment of heavy items.87 These small dwellings lack durability and are vulnerable to the elements, offering little protection from extreme weather conditions.88 The SARThe South Asia Region, comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.17 is one of the most disaster-prone regions in the world,89 and the absence of proper foundations, insulation, and sanitation facilities contributes to the vulnerability of these structures, particularly in events such as severe flooding or wind storms.90 Additionally, a recent study at a kiln in Pakistan found that 71.6% of surveyed kiln residents slept and cooked in the same room, and 73% did not have a toilet facility. In a Nepal study, two-thirds of the surveyed brick kilns provided toilet facilities, but nearly all of them failed to provide women’s health services or childcare facilities.91 This selective provision of facilities contributes to the negative health consequences experienced by kiln workers and their families living onsite.

Kiln Chimney Construction

Photo by M Mahbub A Alahi

In Pakistan alone, there were upwards of 20,000 brick kilns operating in 2023, with 20–30% of their national coal consumption stemming from the brick sector.92 This coal is used primarily to power the kiln chimney, where the clay bricks are fired after molding. Some of the most common types of brick kiln chimneys include Bull's Trench Kilns (BTK), Zigzag Kilns, and Hoffman Kilns. Bull's Trench Kilns employ a continuous firing process with a permanent chimney. This design is the most frequently used in the region, with over 70% of brick production in India relying on BTKs in 2011.93 Green bricks of raw clay are stacked high in an oval around the chimney and covered with loose dirt and ash, which acts as an insulator to seal heat within the bricks from the fires underneath. The fires run continuously, with workers called “firemasters” standing atop the covered stacked bricks to feed fuel such as coal and biomass fuels through holes along the top where they stand.94 The chimney, standing between 67–125 feet tall, provides a draught that sustains the operation of the firing process and functions as a flue for the dust, smoke, and other particulate matter (PM) produced throughout that operation to be released into the air. While Bull’s Trench kilns are cost-effective, they contribute significantly to environmental issues due to inefficient combustion, which leads to high emissions of pollutants such as PM, sulfur dioxide, and carbon monoxide.95 Over time, various models of kiln chimneys have been constructed in an attempt to improve air pollutants emitted from them, but because Bull’s Trench kilns are cost-effective and already in place, they continue to be the most used chimney.

Zigzag Kilns, an improved design, aims to address these concerns by enhancing fuel efficiency and reducing emissions. The primary difference between these and BTK is the pattern of the airflow through the chimney, which follows a zigzag pattern through bricks stacked in a rectangular shape around the chimney. This pattern increases the distance of the airflow path, thus improving combustion of fuel and temperature maintenance.96 Subsequently, overall emissions are reduced by up to 80% compared to the BTK while requiring the same cost of operation.97 Hoffman Kilns, on the other hand, are more advanced and semi-automated, incorporating a circular or rectangular firing pattern. Rather than ash and dirt, the bricks are covered with a solid roof for insulation, and the chimney is about half the height of a BTK or Zigzag. Similarly to the others, solid fuels are fed through holes in the top to maintain the fires inside the brick stack, and emissions are released through the chimney.98 While measured data on Hoffman emissions is not as developed as other types of kilns, they are considered to be more efficient in terms of energy and production. Additionally, the solid roof decreases the generation and spread of particulate matter as there is less dust breathed in by firemasters and other laborers, but the design costs nearly twice as much as the BTK to operate and maintain.99 While these chimney improvements bear high potential to mitigate brick workers’ exposure to hazardous air quality, the lack of infrastructure investments by kiln owners prevents their broader implementation, thus perpetuating dangerous working and living conditions for laborers.

Hazardous Air Quality

Brick kilns produce considerable amounts of dust and kiln emissions, which pose a significant threat to kiln residents’ health as they live and work in a space of uninterrupted hazardous air quality for at least 6 months of the year.

Industry Emissions

Industry emissions are the primary source of air pollution in the SAR. A 2010 study of brick kilnA facility used for the production of bricks through a process of firing clay or other raw materials. Kilns are large, oven-like structures where bricks are fired at high temperatures to harden them. Brick kilns can vary in design and technology, but they generally consist of a firing chamber, where the bricks are stacked and heated, and a chimney to release smoke and gasses produced during the firing process.11 emissions in South Asia found that per one million tons of bricks produced, 1,750 tons of PM10 (particulate matter 10 micrometers in diameter) is released.100 Particulate matter is the scientific term for a mixture of solid and liquid particles found in the air, which can cause serious health problems as they are inhaled.101 Particulate matter, carbon monoxide, sulfur, and heavy metals are released from brick kilns depending on the type of fuel burned, which typically includes coal, animal dung, and other biomass fuels.102 It should be noted that air pollution coming directly from brick kiln emissions ebbs and flows throughout the year due to their seasonal operation. In Nepal, the city of Bhaktapur is one of the most polluted districts in the country, where most of Kathmandu Valley’s brick kilns are located. Tools measuring PM10 levels in Bhaktapur recorded a 178% spike during the first two months of the kilns’ reopening after the wet season.103 In addition to the pollution caused by kiln operations in Bhaktapur, strong winds reliably flow from Kathmandu to kilns in Bhaktapur, carrying significant pollution from industry and vehicles there.104 A study conducted in the Greater Dhaka region of India found that particulate matter concentration in December and January—peak kiln operation months—was at least twice as high as during other measured months.105 It is estimated that up to 50% of PM2.5Represents particulate matter (PM) that is 10 or 2.5 micrometers in diameter.15 in Dhaka during the winter months and 17% of Bangladesh’s comprehensive yearly CO2 emissions come from brick kilns.106 These percentages do not factor in other particulate matter sources from brick kilns, such as stirred dust, nor do they account for other pollutants from other industries or activities that contribute to hazardous air quality in the area.107

Indoor Air Pollution

The primary source of indoor air pollution (IAP) is the burning of biomass fuels—plant- and animal-based renewable organic material such as wood or dung—for cooking and heating.108 While kiln-specific data on IAP from biomass fuels is limited for the SAR, the practice accounts for 10% of the globe’s and 61% of South Asian households’ primary energy use. Approximately 3.8 million deaths are attributed to IAP each year, with roughly 44% of those deaths occurring in South East Asia.109,110 A 2019 study conducted in Nepal detected IAP in 80% of participating households.111 A separate study of brick kiln households in Nepal found that 100% of the study participants cooked inside their homes with no ventilation to the outdoors, and 60% used wood as their primary fuel source.112 Forty-nine percent of India’s population relies on wood as a primary fuel source for cooking and heating, while 94% of rural and 58% of urban Pakistani households rely on biomass fuels.113,114 As previously noted, the ventilation of brick kiln homes is poor, and therefore not conducive to healthy indoor air quality, particularly for those burning solid fuels inside or near their homes.

Consequences

Poor Physical Health

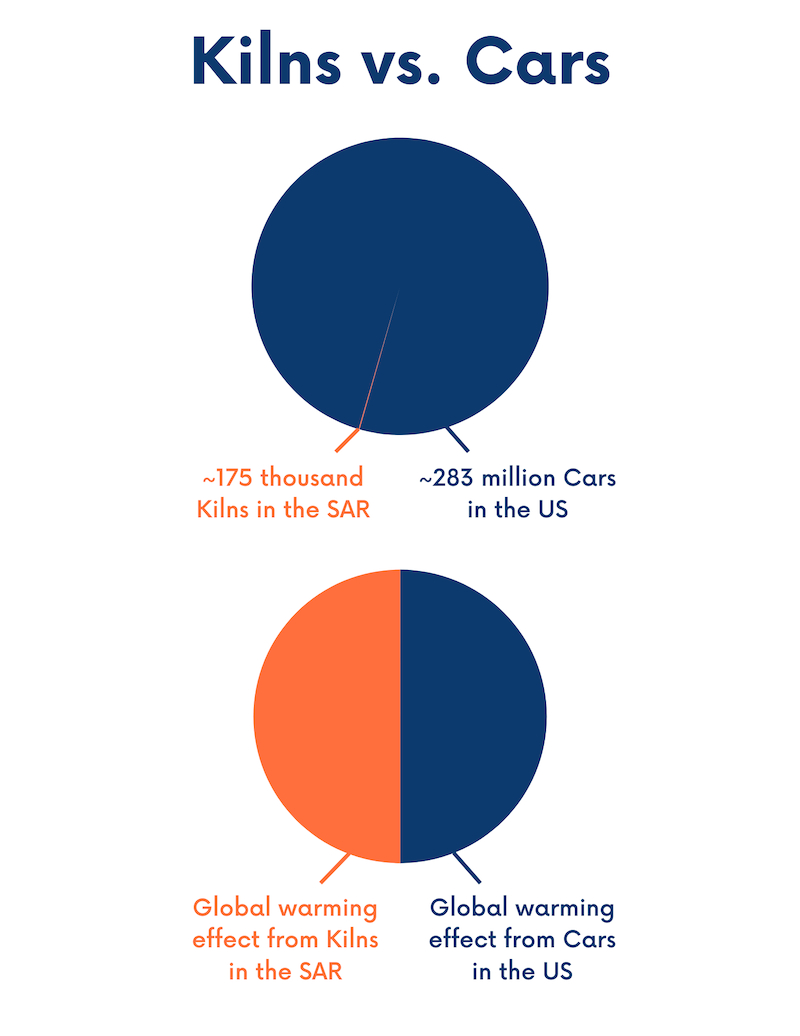

Brick kilns across South Asia have a global warming impact equivalent to that of all passenger cars in the United States.115 Air pollution from these kilns kills tens of thousands of people each year as a result of respiratory and cardiovascular disease, with approximately 4.2 million premature deaths tied to outdoor air pollution and 3.8 million deaths resulting from indoor air pollution.116,117 Eleven percent of deaths in the SARThe South Asia Region, comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.17 result from air pollution, leading to 58 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in South Asia during the year 2019.118 The World Health Organization defines a DALYDisability Adjusted Life Year. The World Health Organization defines a DALY as representing “the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health.”13 as representing “the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health.”119 In Nepal’s Kathmandu Valley, it is estimated that 36% of total suspended particles and 28% of particulate matter smaller than 10 microns come from brick kilnsA facility used for the production of bricks through a process of firing clay or other raw materials. Kilns are large, oven-like structures where bricks are fired at high temperatures to harden them. Brick kilns can vary in design and technology, but they generally consist of a firing chamber, where the bricks are stacked and heated, and a chimney to release smoke and gasses produced during the firing process.11.120 High percentages of particulate matter from brick kiln worksites and living conditions carry detrimental health consequences for workers within these kilns and community members surrounding them due to their high consistent exposure. According to reports, some of these consequences include a significantly higher incidence of chronic cough (31.8%), chronic phlegm (26.2%), and chest tightness (24%) for workers exposed to pollution from brick kilns compared to their counterparts in other factories, where the prevalence rates are notably lower (20.1%, 18.1%, 0% respectively).121

Additionally, air pollution carries significant risks to other bodily functions such as the cardiovascular and central nervous systems. Much of this harm stems from the presence of particulate matter in the air people breathe as respiration opens the primary entry points for particulate matter to enter the human body.122 Exposure to air pollution—particularly PM2.5Represents particulate matter (PM) that is 10 or 2.5 micrometers in diameter.15—has been linked to the development of heart disease or worsening of preexisting cardiovascular problems. Heart attacks, decreased life expectancy, and cardiovascular disease-related mortalities are all expected outcomes of short- and long-term exposure to PM2.5.123 Air pollution damages cells and inflames the central nervous system, leading to health problems such as neurological disorders, permanent brain damage, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease.124

Photo by M Mahbub A Alahi

Maternal and infant mortality in India is directly linked to indoor air pollution from burning solid fuels. Women and children remain most susceptible to health risks such as these because they historically spend more time inside the home.125 In India, the use of biomass fuels such as wood and dung is found to increase the probability of low birth weight by 49%. Exposure to indoor air pollution related to these fuels during pregnancy increased the risks of stillbirths by 50%.126 Female brick workers are found to be twice as likely as non-brick working women to experience spontaneous miscarriages and abortions.127 Additionally, one study found that 16% of the female participants in Pakistan brick kilns were malnourished and fighting respiratory, skin, and kidney diseases.128 These health problems were attributed to the metals and gasses deposited in soil and water near their brick kiln communities as a result of kiln emissions.129 These deposits adversely affect the nutritional value of crops consumed by community members by injuring the development of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids of select plant species, limiting the nutrients their bodies receive from meals.130,131

Child Labor

Child laborChild labor refers to the employment of children in any form of work that deprives them of their childhood, impedes their ability to attend school regularly, or is harmful to their physical, mental, social, or moral development.12 is a common consequence of poverty and seasonal labor, and is, therefore, a common consequence of brick labor, with brick labor identified as one of the most dangerous forms of child labor.132,133 Child labor is the exploitation of children under the age of eighteen through work, in both formal and informal sectors, under harmful conditions that negatively affect them physically, mentally, socially, and educationally.134 In the SAR as a whole, 16.7 million children ages 5–17 are engaged in some form of child labor.135 Approximately 5.8 million of these children live in India, 5 million in Bangladesh, 3.4 million in Pakistan, and 2 million in Nepal.136 Proportionally, Nepali children are at the highest risk in the region of child labor, as one-fourth of the population of children 5–17 years of age are involved.137

About 50% of all child laborers at Nepali brick kilnsA facility used for the production of bricks through a process of firing clay or other raw materials. Kilns are large, oven-like structures where bricks are fired at high temperatures to harden them. Brick kilns can vary in design and technology, but they generally consist of a firing chamber, where the bricks are stacked and heated, and a chimney to release smoke and gasses produced during the firing process.11 are under the age of 14, with 75% of the total child laborers working an average of 12 hours per day.138 An estimated two-thirds of all child brick laborers in Nepal are male.139 Children and families belonging to ethnic minority castes – such as Janajati, Dalit, and Madhesi – are especially vulnerable to bonded labor and verbal or physical abuse within kilns because of the stigma of inferiority applied to them by the broader society.140 Additionally, children working in Nepali brick kilns are twice as likely to be sick as their non-brick worker peers, with 60% of them suffering from severe health concerns linked to their labor. Eighty-eight percent of surveyed child laborers discontinued their school attendance during the brick season.141 While data specific to brick kiln child labor in Bangladesh is underreported, it is known that 5% of the global population of working children are found in Bangladesh with brick labor cited among the most common forms of child labor, making child labor a prevalent issue in the country.142,143 Bangladesh’s child brick workers are deemed particularly vulnerable because the country’s labor laws are not applied to children working in informal sectors. Bangladesh’s low fines and time-intensive legal processes do not provide sufficient motivation for companies to abandon child labor violations.144 In Pakistan, brick kilns are the most common site for child labor, with youth working between 5–8 hours per day for their families.145 Here, children are frequently born into debt bondage and work alongside their family members in bonded labor from a young age. Pakistan’s “peshgis” system of bondage withholds families’ freedom to leave the work site, requiring a minimum quota of 1,000 bricks produced per day without access to safety materials such as gloves, masks, or shoes. If families do not meet this brick quota, they are threatened with physical punishment up to death.146 A study in India found that in just one district, over 25,000 children of migrant workers at brick kilns were engaged in child labor while another report states that up to 40,000 children in the Indian state of Haryana are engaged in brick labor.147,148 The children in this report were described as working under threats of physical violence, were prohibited from leaving the kiln site, and often did not receive promised wages alongside their families.149 To participate in this brick labor, Indian children begin work before sunrise to sieve coal dust and prepare the clay for the bricks. Conditions include standing in knee-deep water and mud for hours at a time, working close to fires, carrying up to 24 kgs of bricks around the kiln site, and exposure to dangerous health hazards and diseases for up to 14 hours per day. If these children do not contribute to brick production, then they are expected to tend to their siblings and household chores while their parents work.150 These conditions and expectations negatively impact not only the child’s health but also their educational opportunities and literacy, as they are kept out of school during the brick season and subsequently fall behind their classmates when they return to school in their rural homes during the off-season.151

Low Wages and Poverty

The labor-intensive nature of brick production, coupled with inefficient technologies, contributes to exploitative working conditions on kiln sites. Although brick kiln work is a complex of many occupations, an overwhelming majority of workers in the kilns (around 80%–90%) are brick molders, while other categories of workers such as firemen working the kiln, horse-cart drivers transporting unbaked bricks, workers who stack unbaked bricks into the oven, and workers who unload baked bricks from the oven are also present.152 The wages of these categories of workers vary depending on the level of skill required and the commonly associated caste group.153 The informality of the sector results in the absence of standardized wage structures, leaving these individuals vulnerable to exploitation, with low and inconsistent incomes that often fail to provide a sustainable livelihood.154 Nearly 79% of surveyed brick workers in India deemed themselves “victims of exploitation,” while 93% reported themselves illiterate, and 94% considered themselves in a permanent state of poverty.155 While some kiln positions receive fixed salaries, depending on the kiln, many laborers are paid daily by brick.

Image by Bishnu Sarangi from Pixabay

In Pakistan, laborers commonly earn anywhere between 12–150 rupees ($0.14–1.80 USD) per 1,000 bricks produced, according to their job tasks and the quality of their bricks.156,157 Nepali kiln workers who are paid by brick earn between $9–10 USD per 1,000 bricks molded and $21.4–28 USD per 1,000 bricks transported.158,159 Nepali workers are paid a monthly salary typically between $164–205 USD per month.160 For reference, the average cost of living for a family of four in Nepal is approximately $1,340 USD per month, or $380 USD per month for a single individual.161 Both of these figures exclude rent expenses.162 This discrepancy in average expenditures versus expected income for brick laborers delineates how poverty and debt-bonded labor are preserved among this population as their monthly income is insufficient to cover their basic needs, let alone repay their kiln debts. Additionally, the lack of social protections, education, and healthcare benefits for these workers in the SARThe South Asia Region, comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.17 reinforces the cycle of poverty as they struggle to break free from the systemic challenges associated with working in brick kilns.

Practices

GoodWeave

GoodWeave is an international organization that aims to address child, bonded, and forced labor around the globe. Established in 1994 and based in Washington DC, it partners with over 20 countries in various sectors and industries to bring higher transparency to supply chains and safety to industry laborers.163 Originally focusing solely on the carpet industries of South Asia, GoodWeave has since expanded its efforts to target additional industries that commonly participate in bonded labor, such as textiles, jewelry, and bricks. With a nonprofit structure, GoodWeave’s programs are sustained by individual and organization donations, including support from the US Department of State and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Additionally, this nonprofit is the recipient of several awards from reputable foundations such as the Skoll Award for Social Entrepreneurship, the Schwab Award for Social Entrepreneurship, and the EXCEL award for Nonprofit Leadership from the Center for Nonprofit Advancement.164

GoodWeave International's theory of change aims to combat child and forced labor within concealed supply chains whose labor and outsourcing extend beyond factory boundaries.165 A supply chain refers to the sequence of processes involved in producing and delivering a product or service, from raw materials to the end consumer. Having a transparent supply chain is crucial for workers as it ensures visibility into working conditions, wages, and treatment throughout the production process, promoting accountability and fair labor practices.

GoodWeave employs a multi-faceted approach to address this pervasive issue, with its first step being the enhancement of visibility for hidden laborers, both children and adults. This approach is accomplished through partnerships with companies committed to examining their supplier networks to reveal inadequate monitoring of production and protections for their laborers.166 Additionally, GoodWeave strives to “offer remedy” by carrying out unplanned inspections of primary, subcontracted, and home-based sites. Doing so mitigates labor exploitation as manufacturers are more likely to strive to pass these inspections at any given moment, due to their unplanned nature.167 If a business fails to pass the inspections, it forfeits the benefits GoodWeave provides. Another important aspect of this organization’s theory of change is the prevention of recurring child and forced labor through addressing root causes. GoodWeave engages local stakeholders to implement social and educational community programs among the workers in order to improve their rights and education.168 Ultimately, GoodWeave extends its impact by leveraging practices that are proven to mitigate child and bonded labor, and assist other organizations in scaling their success model. The organization amplifies its indirect impact through the design and execution of research, projects, and advocacy work intended to eradicate child and forced labor in supply chains.169

Started in August 2013, GoodWeave’s Better Brick Nepal (BBN) initiative has partnered with a number of stakeholders in Nepal, including government programs, nonprofit organizations, and brick kilnA facility used for the production of bricks through a process of firing clay or other raw materials. Kilns are large, oven-like structures where bricks are fired at high temperatures to harden them. Brick kilns can vary in design and technology, but they generally consist of a firing chamber, where the bricks are stacked and heated, and a chimney to release smoke and gasses produced during the firing process.11 companies, to address the issue of child and bonded labor in Nepali brick kilns. Primarily funded by Humanity United, this initiative employs multiple fair labor policy enforcements and protections for kiln workers in partnership with the Global Fairness Initiative and local organizations.170 The model centers on certified better bricks by establishing incentives for brick kiln owners to improve their implementation of labor rights through membership in the BBN initiative. Such incentives commonly stem from market influence. BBN’s model developed their official standard to enforce requirements tied to laborers’ working and living conditions, wages, and treatment during employment.171

Impact

A series of more specific directives are included beneath each principle, including the prohibition of laborers aged 14–18 working between the hours of 6 pm and 8 am, the enforcement of legal minimum wages, and the provision and maintenance of potable water and sanitary facilities on-site.172 As kiln owners adopt this standard, BBN assists in building the kilns’ capacities, along with other members of their supply chains, to aid in achieving the requirements and eventually receiving an official BBN certification.173 Lastly, kilns who receive BBN Member status receive resources for interventions that improve their profits and productivity, which serves as a major incentive for kiln owners to participate and maintain their BBN Standard.174

Working with a tiered system, the BBN initiative is organized in stages to allow for phased progress among participating kilns. The first stage in the program is “Applicant Kiln”, the starting point for every new kiln. In this stage, the kiln owners can expect to participate in core training, program orientation, and technical assistance. Following the completion of this orientation, the sites move into the “Member Kiln” phase. Here, kilns must be audited and verified by an official GoodWeave BBN representative. Owners then enter a 3-year minimum engagement with BBN to align their sites and systems with the BBN Standard requirements. In exchange, the BBN team networks the kilns with buyers looking for ethically sourced bricks and offers aid in improving aspects of the kilns’ business. A kiln becomes a “Certified Kiln” (stage 3) when they are deemed “in compliance” with the BBN Standard. In this stage, Certified Kilns are prioritized in BBN’s marketing and business support on the condition they continue to comply with the standard and commit to zero children and bonded labor on their sites. Currently, the BBN initiative is implemented in approximately 40 kilns in 11 Nepali districts, in partnership with 5 local organizations aiding in the sustainability of this program.175

As of October 2020, 11 kilns in Nepal have reached “Certified Kiln” status.176 Outside of this figure, specific data tied to BBN’s outcomes and impact are currently unavailable to the public. However, GoodWeave publishes a thorough annual report detailing the outputs of its international programs combating child and forced labor combined. In the year 2021, GoodWeave partnered with more than 400 companies around the world to restore nearly 9,000 children to freedom and protect over 101,000 laborers under their standards.177 In partnering with these companies in over 20 countries, more than 44,400 children have been provided educational opportunities, and 86% of respondents to GoodWeave’s partner survey share that this partnership has improved their business’s reputation.178

Gaps

GoodWeave’s programs contribute substantially to the detection, mitigation, and rehabilitation of child and adult laborers engaged in forced or bonded labor, but some gaps remain. Measurement of outcomes and impact tied directly to Better Brick Nepal is lacking. This gap makes it difficult to monitor the progress and success of the BBN program. Robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are essential to assess the impact of the better brick standard and kiln partnerships, but gaps in this area hinder the ability to measure outcomes and make data-driven decisions for the BBN initiative. As BBN and its clients seek to continuously improve the program and their businesses through this initiative, it is paramount that they collect data on not just outputs, but also the outcomes and impact of the program on rates of child and forced labor, and living and working conditions in Nepali brick kilns. This effort will not only improve these businesses’ work but will additionally boost credibility and improve visibility among other kilns in the country, spreading the mission and impact of BBN and GoodWeave to more workers and their families.

Climate and Clean Air Coalition

The Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC) is a voluntary partnership of governments, intergovernmental organizations, businesses, scientific institutions, and civil society organizations. Launched in 2012, the CCAC aims to address short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) to reduce their impact on both air quality and climate change.179 SLCPs include methane, black carbon (soot), hydrofluorocarbons, and tropospheric ozone. These pollutants have a shorter atmospheric lifespan than carbon dioxide, yet their impact on air pollution levels remains detrimental.180 The CCAC focuses on strategies to mitigate the emissions of these pollutants, providing a more immediate yet still impactful approach to combating hazardous air pollution.181

Because the CCAC operates through a collaborative approach, it has built a number of partnerships in various countries around the world to jointly address air pollution on small and large scales. Founded by the governments of Bangladesh, Ghana, Sweden, the United States, Canada, and Mexico in conjunction with the United Nations Environment Programme, the CCAC now works with over 160 governments to reduce the rate of global warming by raising awareness and urgency to act on SLCPs and develop interventions applicable to sectors that emit these pollutants.182

Regarding brick kilns, the CCAC provides significant funding for partners and brick kiln owners that is necessary for kiln modernization. Kiln modernization is one of the most effective ways to preserve the job market that brickwork provides while also improving the harmful environmental and health effects of the process. The CCAC commonly sponsors projects in the SARThe South Asia Region, comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.17 that foster local partnerships for brick kilns. These partners recognize that modernizing kiln technology is one of the most effective ways to mitigate their emitants, but dually understand that significant barriers—primarily financial—to adopting that technology persist for kiln owners. While the CCAC’s approach may vary slightly depending on cultural nuances and needs, the goal of reducing SLCPs through partnerships remains the same across projects. An example of one of its activities can be found in the 2017 project it funded in Bangladesh, which was implemented by the United Nations Environment Programme in partnership with the Frankfurt School of Finance and Management. Working with local actors in Bangladesh to address the barriers that limit the adoption of modern kilns, this project aimed to provide technical assistance to Infrastructure Development Company Limited (IDCOL). IDCOL is a government-owned non-bank financial institution in Bangladesh that provides financing to sponsors who can construct cleaner kiln technology, thus aiding in the motivation for kiln modernization. IDCOL proposed to invest $50 million USD over the course of 5 years to renew the stock of operating kilns in Bangladesh, replacing outdated kilns such as the Bull’s Trench with more energy-efficient ones. The CCAC is involved in a number of similar brick-sector projects in an effort to improve air quality and quality of life for affected communities.

Impact

Results from CCAC’s 2019–2020 annual report show significant strides made in the SAR from its efforts. Data directly tied to the aforementioned program in Bangladesh is difficult to find, but similar projects in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal are included in this more recent report. For example, through the CCAC and partners’ work, 700 brick kilns in Pakistan were given preference for loans after converting to the energy-efficient zigzag technology.183 In Nepal, nearly $3 million USD in funding was granted to convert 60% of Nepali kilns to the zigzag model, resulting in a 75% decrease in carbon dioxide and a 41% decrease in black carbon pollutants from kilns.184 The CCAC has encouraged Bangladesh’s kilns to switch from traditional fired bricks to alternative bricks (AB), and has established three business plans for different types of ABs and implemented 69 groups of technical training sessions for experts such as engineers or masons.185 This work has yielded promising results, as 90% of targeted populations showing improved understanding of greener brick technology.186

Gaps

While the CACC’s programs surely prove effective in mitigating SLCPs, some unintended negative consequences of its work persist. The push toward greener brick technologies commonly evolves into automated technologies, such as the Makrail Auto Green Bricks project underway in Bangladesh.187 This transition from manual brick kilns to more mechanized green brick kilns can have unintended consequences for brick workers’ job security as the mechanized approach requires fewer people to operate the kilns and produce bricks.188 While the adoption of green technologies is a positive step towards environmental sustainability and improved working conditions, the shift to automated processes may lead to a reduction in the demand for manual labor, resulting in job loss and removing a source of income for many brick workers. As the industry modernizes, it becomes imperative for stakeholders, including policymakers and employers, to proactively address the potential negative impacts on job security. This may involve implementing social safety nets, retraining programs, and diversification strategies to ensure that the workforce is not disproportionately affected by the shift to greener practices.

Preferred Citation: Ball, Cambrie. “The Harmful Effects of lIving in Brick Kiln Communities in the South Asia Region.” Ballard Brief. April 2024. www.ballardbrief.byu.edu.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints