Violence Against Refugee Women in the MENA Region

Photo by Ahmed akacha from Pexels

By Genevieve Cole and Harriet Huang

Published Winter 2022

Special thanks to Robyn Mortensen for editing and research contributions

This brief will focus on refugee women coming from the MENA region. The research and analysis throughout the brief include MENA refugee women currently in refugee camps, on the path between their home and their host country, or at their host country.

Summary+

Refugee women of the Middle East North Africa (MENA) Region are exposed to violence in a variety of ways along their refugee journey. Once within refugee camps, refugee women face high risk spaces for violence, inhibited privacy, as well as unequal gender based power relations between themselves and predominantly male staff. Outside of refugee camps, lack of and improper implementation of cross-border policies allow trafficking networks, authority figures, and other perpetrators of GBV to harm refugee women without fear of repercussions. Victims of GBV can experience a variety of short and long term physical and mental health concerns that can affect them even after they have left their origin country and refugee camp. Victims of GBV can also experience social stigmatization where they can be outcasted, shamed, and blamed by members in their community. As a way to prevent and assist victims of gender based violence (GBV), an organization based in Turkey called Support to Life has implemented a project to help Syrian refugee women learn and understand their rights as women in order to stop cycles of GBV in their lives.

Key Takeaways+

Key Terms+

Refugee—A refugee is anyone who has fled their own country to another country due to war, persecution, or violence, forcing them to try to find safety in another country1 across political boundaries.2, 3 Conflict can be caused by war or persecution based on race, political unrest, or religion.4

Gender Based Violence (GBV)—Gender-Based violence refers to harmful acts directed at an individual based on their gender. It is rooted in gender inequality, the abuse of power and harmful norms that not only impacts on the individual but ultimately strengthens females subordination and extends male authority and control more widely.5, 6

Sexual & Gender-based Violence (SGBV)—Refers to any act that is perpetrated against a person's will and is based on gender identity, gender norms, and unequal power relationships.7 It includes physical, emotional or psychological, and sexual violence, and denial of resources or access to services.8

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)—Physical and sexual violence from a former or current partner or spouse.

Refugee Camp—Facilities to provide temporary housing and placement for people fleeing their country due to political conflict, war, poverty, or persecution.

Host country—A country that has granted asylum to a significant number of those who have left their native country as a political refugee.9

Country of Origin—the country where a refugee is native to, or the country where a refugee is originally coming from.10

Stigma—Feelings of disapproval that people have about particular illnesses, circumstances, or ways of behaving.11

Context

What is the MENA Region?

This brief focuses on the refugee women from the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region because this region has had a greater frequency and higher intensity of conflict in the last half century than other regions in the world engaged in conflict.12 In 2011 the MENA region was a region of origin for 7,512,968 refugees and asylum seekers.13 Syria in particular has contributed largely to the refugee crisis in MENA as the home country of 6.7 million refugees in 2020.14 Due to such a large number of refugees, Syrian refugees constitute the majority of research done on refugees from the MENA region.15 Another major country where refugees come from is South Sudan. As of mid-2021, there are 2.2 million refugees who originate from South Sudan.16

Other noteworthy countries that act as host countries for refugees include Afghanistan, Turkey, Pakistan, Jordan, Lebanon, and Iran.17, 18, 19 Turkey hosts the largest number of refugees in the world with 3.7 million refugees in 2020.20 The rapid increase of refugees within the last two decades can be seen in camps such as the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan, which was built to accommodate 60,000 people, but became home to over 150,000 refugees within a year of its construction.21

What type of violence are refugee women exposed to?

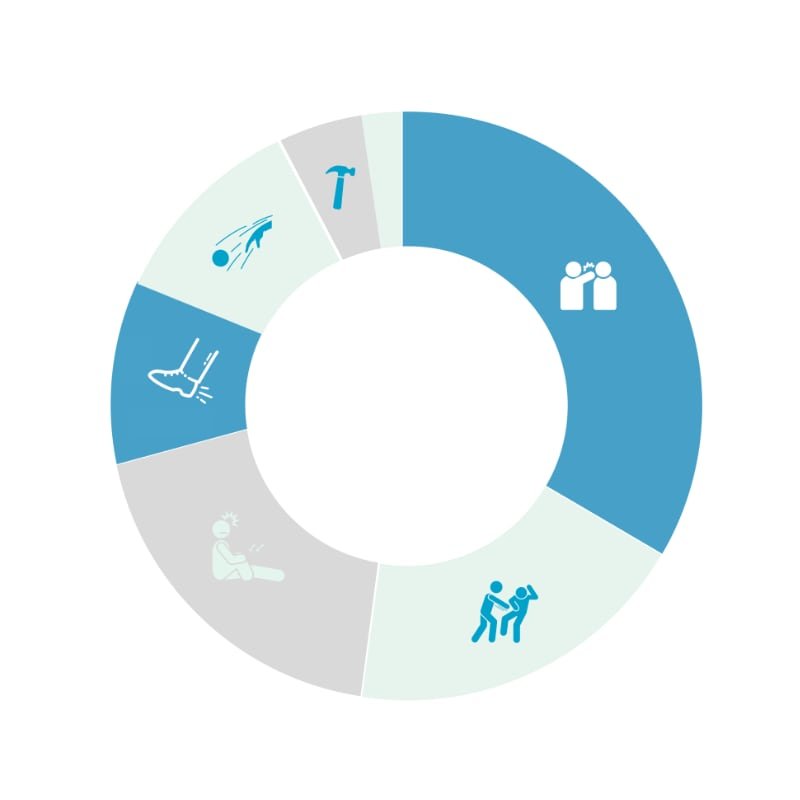

Refugee women are exposed to a variety of violence as they flee from their homes, travel along migration routes, and reside within refugee camps. Some of the violence refugee women experience is rooted in gender-based violence (GBV) which can include sexual, physical, mental and economic harm inflicted in public or in private.22, 23 GBV also includes threats of violence, coercion and manipulation, and intimate partner violence (IPV).24 Intimate partner violence describes instances of physical and sexual violence from a former or current partner or spouse. A 2003 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) report found that the most common forms of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) are sexual violence (rape, sexual abuse, sexual exploitation, forced prostitution and sexual harassment), physical violence (physical assault through the perpetrator slapping, hitting, shoving, kicking, dragging, or throwing items at the victim,25, 26 trafficking in persons), emotional and psychological violence (abuse/humiliation) and harmful traditional practices such as early or forced marriage.27 In a small-scale survey (2015) of refugees, over a quarter of refugee women residing in Lebanon reported exposure to violence, abuse, and SGBV.28 Intimate partner violence and early marriage are other forms of violence that refugee women can experience.29 Participants in a study of refugee women residing in Lebanon as their host country reported that IPV had increased since their arrival as well as early marriage in an effort to ‘protect’ girls from rape.30 In a rapid assessment survey among Syrian refugee women in Lebanon in 2012, some women also reported feeling vulnerable to kidnapping, robbery, and attacks.31

How prevalent is violence against refugee women?

As of 2019, 20% of all internally displaced or refugee women have experienced sexual violence.32 However, female refugees within the MENA region experience violence to an even higher degree. While a survey of 80 countries conducted by the WHO in 2010 showed that 30% of women reported physical and sexual abuse, the number rose to 37% in the Middle East, with 32% of Syrian refugee women living in Lebanon and Jordan reporting instances of spousal violence in 2015.33 A study of Afghan refugee women living in Iran conducted from 2016 to 2017 revealed that approximately four-fifths of the surveyed population (79.8%) had experienced a form (minor or severe) of physical, sexual, psychological, and injurious IPV during the past year.34

In a case study of migrant and refugee women living in Morocco, all of the interviewees claimed to have been victim to some form of sexual violence, including coerced sex and sexual harassment.35 Refugee women may also experience multiple forms of violence simultaneously, as demonstrated by a study gathered among Afghan refugee women in Iran. Among all the women surveyed who had experienced IPV, over a quarter of them (27.7%) had experienced multiple forms of violence from their intimate partners in the past 12 months.36

As individuals and families become refugees, they will often experience an increase of violence from their partners, as demonstrated through surveys from Syrian refugee women upon their arrival in Jordan in 2013.37 Findings indicated that 28% of Syrian refugee households left Syria due to specific fears of violence including GBV, and some disclosed experiencing increased levels of violence since arriving in Jordan.38 In 2012, the International Rescue Commitee in collaboration with the ABAAD-Resource Center for Gender Equality, located in Lebanon, conducted a rapid assessment among Syrian refugee women and found that while rape and sexual violence were found to be the most extensive form of violence experienced by women prior to flight, IPV, early marriage, and survival sex had increased in frequency since arriving in Lebanon.39

It is important to recognize the difficulty of collecting data when it comes to violence against refugee women in the MENA region due to fear, insecurity, a lack of justice protection, and insufficient reporting mechanisms.40 This leads to massive underreporting and creates barriers to collecting information.41 Ongoing conflict within this region also influences the quality and availability of data relating to displacement.42

Who are the refugee women from MENA?

Data shows that from 2010-2019, there has been an average of an increase of 2.9 million displacements per year in the MENA region.43 As of 2020, there were about 9 million refugees in MENA.44 Female refugees make up about 50% of refugees worldwide, and45, 46 as of 2019, approximately 26% of all internationally displaced people were females between the age of 18-59 years and 5% were females between the age of 12-17 years.47 Countries with many refugees in the MENA region compare similarly. In Palestine, 28% of refugees were women between the age of 18-59 years and 6% were females between the age of 12-17 years.48

Gender-based violence, including SGBV, is not unique to only female refugees. In 2016, 20% of rape cases were reported by refugee men in Lebanon.49 However, this brief is focused on female refugees because they experience GBV disproportionately more than male refugees.50 In a report done on 60 studies around the world on refugees who have experienced sexual violence, the majority of the victims were women in 89% of the studies.51

Who are the perpetrators?

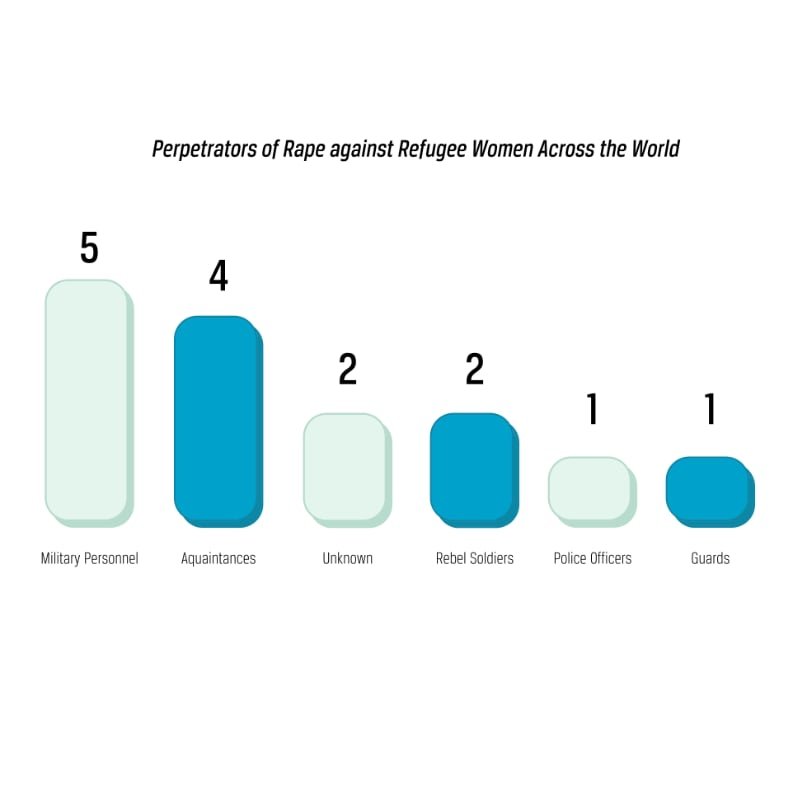

From 18 studies done on refugee women experiencing rape throughout the world, 10 included perpetrators that were intimate partners, 5 military personnel, 4 acquaintances, 2 unknown, 2 rebel soldiers, 1 police officers, and 1 guards

There is limited research and data on perpetrators of GBV, since most of the research and studies are focused on the refugee women experiencing GBV/violence. In the majority of sexual and gender-based violence, the victim is female and the perpetrator is male.52 As shown in studies done on perpetrators, this GBV is initiated by intimate partners, human traffickers during migration periods, humanitarian agency staff, and security forces within refugee camps.53 As seen in the graph, refugee women who are victims to GBV most frequently report that the perpetrator is an intimate partner. Rates of IPV are much higher than violence from those outside of the home.54 Refugee women are prone to increases in IPV due to husbands and intimate partners reacting with violence to increased levels of stress associated with households entering refugee lifestyles.55

What events have triggered an increase of refugee displacement in the MENA region within the last two decades?

Within the MENA region, individuals and families have forcibly become displaced due a variety of conflicts, such as colonial experiences, civil war, and displacement from conflict and post conflict situations.56 For example, in 2010, many countries within the MENA region that were already hosting several million refugees received new groups of refugees due to the Arab Spring, also known as the Arab Revolutions, displacing existing refugees for a second time from their original country of asylum.57 Since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, 6.7 million more refugees have fled their homes58 The MENA region is also heavily affected by environmental circumstances that lead to the displacement of societies. The three most common of these environmental circumstances are water scarcity, the transboundary nature of water (regarding bodies of water shared across multiple country boundaries) and growing urbanization.59 Over 33 million people were affected by these natural disasters, most of which were displaced from the original location where the disasters occurred.60

Contributing Factors

Consent to Violence to Meet Economic and Travel Needs

Many refugee women give consent to SGBV because their perpetrators offer services or resources that the women would otherwise not be able to acquire due to the restricting influence of poverty. Conflict and forced displacement have often compelled refugee men and women to flee their country with only their children, no belongings and limited money, leaving behind their homes, material goods, social relationships, and financial security.61 As of 2017, 76% of Syrian refugees lived below the poverty line, and more than half lived under extreme poverty.62, 63 Research performed by The Reproductive Health Journal showed that Syrian refugee women who have migrated to Europe conclude that exchanging sex for transportation to another country is common when a woman lacks the funds to pay for it.64 Women traveling alone or only with children are especially vulnerable to attack along migration routes.65 Those providing essential transportation sexually abuse women who do not have sufficient funds, which are the large majority of refugee women, in what has been known as “transactional sex.”66 Examples of violence in these situations are most often presented as rape, sexual assault, sexual exploitation and torture, or physical assault.67, 68 In addition, refugee women are at risk of being put into sex trafficking to continue to pay for their migration.69 In a survey of refugee women who had come to Morocco on buses in 2008, they described how migrants need large amounts of funds to pay smugglers and border guards, and many refugee women may be forced to engage in sex with smugglers to return the services the smugglers provide.70

Refugee women within the MENA Region also consent to sexual extortion from guards and law enforcement along refugee migration routes and within detention centers in order to fulfill economic and travel needs. Reports show that refugee women were promised priority treatment in their cases and faster release if they engaged in transactional sexual relations with guards.71 Within refugee camps or communities themselves, economic need increases womens’ vulnerability for sexual abuse, exploitation, sex trafficking, and coerced sex work as seen in refugee camps in both the MENA Region and one in Europe containing Syrian refugees.72, 73, 74, 75 Insufficient rations and supplies within refugee camps can force women to trade sex with humanitarian agency workers in order to “make ends meet.”76 If there are situations where distributors have a supply surplus, male camp leaders overseeing supply distribution may have the potential ability to use unregulated power to control the disbursement of these excess rations.77

With no means to independent economic sustainment, some female refugee victims of IPV also become reliant upon the income of their male household members, and so she may choose to accept patterns of abuse rather than the possibly worse alternative of leaving.78 Considering that poverty rates are higher in refugee households that do not have a male figure,79 women may be hesitant to leave abusive partners and situations of IPV to avoid increased poverty as well as increased risk of exposure to violence and sexual abuse from others.80, 81 For instance, women’s centers in Lebanon receive victims who have not contacted the police, despite enduring years of violence from their husbands, because they are economically dependent upon their husbands.82 Research with 106 refugee women from the MENA region who had been relocated in England or Wales for asylum reported that 35% felt forced to stay in abusive relationships due to financial destitution.83 Intimate partners may also use violence to limit their refugee partner’s mobility outside of the home, forcing their female partners to rely on their economic support, as was the case in small scale needs assessments of Syrian refugees.84 In a different study among women in Jordan, results suggested that not being financially empowered resulted in an estimated increase of women experiencing any type of intimate partner violence.85 Financial empowerment presents itself as participation in financial decision making, such as regarding income earnings.86 Women who engage in this kind of financial empowerment have a reported decreased probability of experiencing IPV.87 Other global studies also confirm that generally speaking, higher levels of women’s financial inclusion were associated with lower levels of IPV.88

Inadequate Structural Protection Inside & Outside Refugee Camps

Refugee Camp Layout and Overcrowding

Improper camp organization and overcrowding within refugee camps can lead to an increase of violence against refugee women.89, 90 In overcrowded spaces, refugee women will share shelters with other families or individual strangers in spaces that do not provide adequate privacy.91, 92 As the number of refugees entering camps increases, the resources available, including space, dwindle. This leads to many women left to sleep and live in close quarters with others.93 Extended amounts of time living with strangers can result in increased risk of harassment, abuse or sexual exploitation especially in the case of single, divorced and widowed refugee women because they are not already married to a man that could have the potential to protect her.94, 95

Improper design and social structure of camps can also contribute to violence against refugee women, as it establishes high risk spaces for violence against women.96, 97 Location of basic facilities, such as washing facilities and toilets, are typically a considerable distance from where women are encamped.98, 99 This can create risk zones for violence and harassment not only at these facilities but as refugee women walk long distances from camp.100, 101 Some women fear sexual assaults from having to share bathrooms or showers, with unknown men.102 There are even accounts of women refusing food and water for several days in order to avoid using latrines due to their unsafe and unsuitable natures.103 In three field studies of refugee camps, one of which being in Iraq, fear of GBV was impacted by location of sanitation facilities as well as sex and spatial segregation of these facilities.104 Lack of security and lighting within refugee camps in Jordan has also been associated with increased violence.105, 106 A group within the UNHCR found that 83% of reported problems regarding poor lighting and broken locks in the Za’atari camp were found in facilities for women.107 Lighting at popular spots like Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) facilities can deter perpetrators from attacking as lighting allows them to be seen or recognized.108 In reports of women from three refugee camps, including one in Iraq, women reported feeling safer and less vulnerable to GBV when using well lit facilities, especially when combined with increased security patrols and additional lighting within the camp.109

Refugee Camp Staffing

Within refugee camps, women can be exposed to violent situations that stem from unequal gender and power relations from administration and staff authorities.110 Refugee women and children are most susceptible to exploitation by those in positions of power and money during their refugee experience, and these individuals in power can present themselves in the staff of refugee camps.111 For instance, one study performed among Syrian refugees in Lebanon in 2018 found that predominantly male leadership in refugee camps influences the prevalence of violence against refugee women.112 Food distribution processes within refugee camps can lead to heightened masculine dominance over refugee women, in which humanitarian workers, security forces or guards force the women to exchange sexual favors for food or asylum hearings.113, 114 Albeit not within the MENA region but nearby, a 2002 study commissioned by UNHCR and Save the Children-UK in refugee camps in West Africa discovered that many perpetrators of violence against women and children were staff members of distinguished humanitarian agencies, as well as government officials, law enforcement, teachers, and camp leaders, and were generally adult men between the ages of thirty and sixty.115 Due to legal concerns, safety of victims, and limited anecdotal information, the precise data and complete list of NGOs involved are not available to the public, but organizations such as MSF, the American Refugee Committee, Medical Relief International, and the International Federation of the Red Cross were mentioned.116 Improved administration policy regarding the conduction of background checks and training of staff could alleviate the potential for women to experience violence and sexual exploitation from the staff they expect to protect them. Within refugee camps specifically, predominantly male leadership and gender-based decisions can contribute to violence against women.117, 118, 119

Refugee women who have the desire to lead within refugee camps typically face barriers preventing them from doing so as the professional environment within the MENA region is heavily gendered, often placing women in educational, social, or health care based roles while men serve in leadership positions.120 Studies of refugee camps, including within the MENA Region, showed that refugee women were not only interested in planning programs but also had opportunities to do so, but their enthusiasm was restrained by organizational issues such as mismanagement with primarily male staff, lack of effective communication between refugee women and camp administration.121 In one camp, refugee women were able to find success in camp planning, but few camp reports gave similar success stories due to male dominated camp management and staff, such as one Afghan refugee camp in Balochistan.122

Outside Refugee Camps

While many refugees and migrants often travel multiple countries in order to reach their country of asylum, as of 2019 there were no cross-border programs or policies focused on GBV, especially along the routes refugees take to reach asylum in Europe.123, 124 At this time the responsibility of promoting effective staff training directed towards cross-border protection falls on nation states and NGOs in collaboration with volunteers, women’s rights organizations, and civil society organizations.125 As refugee women migrate between countries, they can be exposed to violence from police, migration workers, or border control.126, 127, 128 Morocco is an example of an area within the MENA Region that is particularly dangerous for refugees and migrants. At its Algerian-Moroccan borders where official authority is lacking, organized gangs of migrant men led by chairman rob, attack, and exploit migrants.129 There is also an area between the Moroccan border and the town of Oujda, Morocco that is considered “no man’s land” and unpoliced, allowing trafficking and smuggling networks flourish here as well, as they operate with impunity.130 According to Doctors Without Borders, these networks are responsible for 52% of violent attacks against migrants in this area, as of 2008.131 Their studies also showed that 43.9% of most serious incidents were represented by violent acts committed by Moroccan and Spanish Corps Security Forces, due to a lack of and improper maintenance of policy.132

Inadequate Reporting Policies

A lack of effectiveness on policies surrounding the actions of perpetrators of GBV can prevent offenders from facing consequences and fearing punishment, which correlates with significant increases of SGBV and domestic abuse in refugee camp settings.133 This can also lead victims to fear retaliations if they report, causing underreporting and more perpetrators avoiding punishment.134, 135 The procedures currently in place for reporting violence against refugee women are inadequate because they do not provide proper protection, and many women do not know where to report when members of staff are the perpetrators of the abuse.136 Victims of this violence fear retaliation or that refugee camp staff will withhold essential provisions.137

Efforts to prevent sexual violence are typically insufficient within refugee camps.138 In a study with refugee women from South Sudan, they reported that they did not receive adequate justice from criminal justice systems.139 The participants in this study claimed to have a basic understanding of the criminal justice reporting system, but they experienced long waiting periods for hearings, expensive fees, and lack of respect from police officers.140 Even if refugee women are educated in their local criminal justice reporting system, inefficiencies and other difficulties prevent them from achieving justice and prevent the attacker from receiving consequences.141

Research on refugee women in Pakistan reported that while women face high rates of SGBV and GBV, the large majority of their attackers go unpunished.142 Being registered and identified with the UNHCR allows refugee women to have additional access to services, like clinical care, to aid with the consequences of sexual violence.143, 144 Refugees register through the nearest UNHCR registration center providing identity documentation which can prevent refugees from being sent back to their home country and ensure that refugees receive adequate provisions like food and shelter.145 However, inadequate facilities may prevent host countries from registering high influxes of refugees under the UNHCR.146, 147 A study performed among Syrian refugees in Lebanon in 2018 found that lack of registration and identity cards due to poor policy and rules put in place make the access of legal documents difficult for refugee women, especially within refugee camps.148 Without these legal documents, refugee women are especially at risk of not receiving legal justice for GBV due to their lack of legal recognition.149 In this study with Syrian refugees women in Lebanon, they experienced higher rates of SGBV and IPV in Lebanon, than in Syria, which was tied to their lack of ability to access GBV programs without legal recognition.150

One of the most important treaties regarding women’s rights is CEDAW, Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women.151 This was adopted by the UN in 1979. However, parts of this agreement have been ratified by some countries in MENA based on interpretations of the Shari’a, a system of Islamic law.152 Refugee women in the MENA region are not protected to the same extent as other regions. In the Mena region, 9 countries do not have equality laws that explicitly name gender or their equality is based on Islamic laws that consider men and women to be treated differently.153 Also, only half of the countries in MENA have laws on domestic violence. There is a lack of policies that protect refugee women who experience GBV within a marriage preventing married men from receiving legal punishments when abusing their wives, even if they are underaged.154 In Egypt, marriage is one of the few options to avoid homelessness or deportation for refugee women, so many women will stay in an abusive marriage or marry into an abusive situation remaining unprotected from laws that don’t include IPV.155

In addition, there are no effective policies put into place to hold humanitarian aid workers accountable for GBV.156 The UN has suggested a universal policy for consequences for inappropriate behavior from humanitarian aid workers, but these measures have been found ineffective or have been implemented.157 For refugee women, there are either none or inefficient policies put in place regarding GBV for the men they are forced to interact with daily, from their partners and family, refugee camp workers, humanitarian aid workers, or strangers, putting them at greater risk for GBV.

Negative Consequences

Physical Health

Refugee women can experience a wide variety of negative health consequences as a result of GBV.158 Comprehensive reviews of physical health consequences of IPV, across women of any and all backgrounds, report multiple health outcomes including chronic pain (e.g., fibromyalgia, joint disorders, facial and back pain); cardiovascular problems (e.g., hypertension); gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., stomach ulcers, appetite loss, abdominal pain, digestive problems); and neurological problems (e.g., severe headaches, vision and hearing problems, memory loss, traumatic brain injury).159 A study performed among Afghan refugee women in Iran from 2016 to 2017 revealed that 79.8% of Afghan refugee women had experienced a form (minor or severe) of physical, sexual, psychological, and injurious IPV during the past year.160 The most reported form of IPV by study participants was minor sexual coercion (66.5%), followed by minor psychological aggression (30.9%), and minor physical assault (16%).161 These results affirmed conclusions regarding the increased prevalence of physical abuse among refugee women made by surveys of Afghan refugee camps in Pakistan and in Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan.162

A study published in 2005 studied the prevalence of intimate partner violence in Jordanian refugee camps.163 The study asked married refugee women if they had experienced specific acts of physical violence and the types of injuries they may have suffered.164 The study found that slapping was the most common form of abuse (36.0%), followed by pushing, grabbing or shoving (23.5%), and other unspecified acts of violence (22.9%).165 Lower prevalence rates were reported for kicking or hitting with the fists (12.6%), throwing harmful objects (10.8%), hitting with hurtful objects (7.0), and choking (3.1%).166 When both husbands and wives were interviewed regarding the abuse of wives and the resulting injuries, 3.7% reported bruises, 3.4% reported cuts, scratches or burns, and 2.3% reported miscarriages.167

GBV often leads to sexual reproductive health concerns such as unwanted pregnancies, unsafe abortions, miscarriages, sexually transmitted diseases, infections, and sterility and fistula complications.168, 169, 170 Forced sex by an intimate partner can also result in vaginal and anal tearing, pelvic pain related and unrelated to pelvic inflammatory disease, increased pain associated with menstruation, and cervical neoplasia.171 Instances of sexual assault against younger women is also likely to lead to complications tied to such early childbearing ages, such as death.172 In assessments of reproductive health among displaced Syrian refugee women, violence against women had a strong positive association with menstrual irregularity, severe pelvic pain, and vaginal infections.173, 174 Among nonpregnant women, experiencing conflict violence was significantly associated with similar gynecologic outcomes.175 In another study among Syrian refugee women in Lebanon, an increase in GBV and IPV, as well as lack of emergency obstetric care, high cost of healthcare, limited access to contraception, and forced cesarean sections, contributed to poorer reproductive health and delayed family planning.176

Mental Health

Not only are women victim to physical injury due to GBV, but also mental health harm as well. Analysis from Assisting Marsh Arab Refugees (AMAR), an international charitable foundation based in London, health clinics in the Middle East that treat mental health for refugees found that approximately 78% of patients were female.177 This disproportionate amount of female patients was linked to trauma from GBV.178 In a study performed by The International Rescue Committee in Afghan refugee camps, they found that 56% of women had reported experiencing emotional violence.179 Survivors of sexual assault and GBV report experiencing flashbacks of their assault, as well as feelings of shame, isolation, shock, confusion, and guilt. These types of symptoms, resulting from the trauma of GBV, increase the risk of developing depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and PTSD.180

A different study of Somali women in a Kenyan refugee camp revealed that more than half of study participants reported symptoms of PTSD, moderate to severe depression, or anxiety.181 Their results showed a higher prevalence of mental health disorders among refugee women who experience GBV in conflict affected settings specifically than in the wider, more general refugee population.182 A doctor treating refugee women in Morocco described them as traumatized from their experiences with extreme violence against them during their migration.183 Other studies in IPV reveal that victims of GBV also experience low self-esteem and increased rates of suicidality as compared to their counterparts who have not experienced IPV.184 Experiences of refugee women in Jordan showed that those who were victim to IPV were more likely to think of suicide and attempt suicidal actions.185

It should be noted that the consequence of mental health has also prevented refugee women from reporting cases.186 In a report, Syrian refugee women who experienced abuse were interviewed saying that mental health problems caused by GBV like depression have hampered them from reporting the GBV. Another study showed the correlation between refugee women who experienced SGBV and high levels of depression.187 Mental health caused by GBV leads women to prolong or never receive the help that they need.

Research on refugees from MENA that migrate to the UK have shown that they have a difficult time integrating into new countries due to mental trauma from SGBV experienced as a refugee.188 There are long term mental effects for refugee women, like trying to raise a child who was the result of a sexual attack in a foreign country.189 In addition, some refugee women still experience SGBV in their new countries. In the same study, 32 of 103 refugee women participants experienced SGBV in their origin country and in the UK.190

Social Stigma

Photo by Ahmed akacha from Pexels

Due to cultural standards prominent in the MENA region, refugee women who experience GBV are faced with various forms of social stigmatization. Reports show that stigmatization of Syrian refugee women that are victims of GBV can present itself as shame, social isolation, outcastement, loss of political, economical and social standing standing191, blame for the incident(s), and even honor killings.192 Specifically, SGBV can lead to discrimination, exclusion, and inequality.193 Refugee women in the MENA region are especially susceptible to stigma because of common cultural expectations.194

Often, those who experience GBV, especially SGBV, experience strong feelings of shame195 This was found proven for refugee women in a case study in Egypt.196 One cause of shame comes from the blame of sexual violence being placed on the victim, and not the attacker in many cultures in the MENA region.197 There are lots of feelings of shame surrounding the loss of female virginity outside of marriage. In addition, research on refugee women with HIV shows that there is stigmatization surrounding the possibility of having contracted HIV for SGBV victims.198 Another cause of shame is rooted in the stereotypical gender roles that are commonly accepted in countries in the MENA region.199 Generally, in the Arab culture, men are seen as the head of household and should be honored by their wives.200 It is socially unacceptable to publicize IPV for women, and seen as disrespectful to their husbands.201 Sudanese refugee women in Egypt also fear the shame in Sudanese communities that follow reporting their husbands.202 Fear of stigma also correlates with forced and early marriages among refugee women as family members wish to “protect” women from rape and its associated social consequences, such as the inability to marry due to being a victim of sexual assault.203

In a study with female refugees in the Middle East, often there are lots of feelings of shame surrounding the loss of female virginity outside of marriage, which is common for many victims.204 This stigma follows not only an individual girl, but her whole family. Some girls and women can be expelled from their families or divorced from their husbands205 while others may be outcasted if they have a child resulting from rape.206 Chances of future marriage are decreased, as many cultures in the MENA region value the virginity of a woman.207 In many societies, lack of marriage can greatly inhibit a woman’s opportunity for rights like owning property, financial independence, and jobs.208

Victims often choose to remain silent after being a target of GBV in fear of further suffering from being ostracized by their community of peers and family, or possibly bringing humiliation onto their family.209, 210 For refugee women in Egypt, they expect little support from police officers if they choose to report IPV, since there is stigmatization from police officers.211 Syrian refugee women in refugee camps shared that they would admit to knowing someone who has experienced GBV, but not if it were themselves due to a fear of lifelong stigmatization.212

Another note of importance is that stigmatization from GBV contributes to poor mental health and physical health for refugee women.213 Victims of GBV can experience lower self confidence after suffering stigmatization from their community.214 GBV is not an isolated issue and can affect many aspects of family dynamics. If a refugee woman is seen as being at fault for GBV, she may be physically punished by her husband or even her parents. Though not noted in the research as participating in the punishment, the research shows that in-laws may even encourage these punishments.215

Best Practices

Support to Life

One organization based in Turkey that focuses on female refugees from the Syrian refugee crisis is Support to Life.216 Support to Life has a variety of different programs that focus on various humanitarian efforts, but this brief will be focusing on their project surrounding refugee women done in 2018 that was funded by the European Union and the UN Women’s Fund.217 This project was done in southern Turkey and had three goals: to enable the volunteers to educate and help against GBV, inform and educate refugee women on current legal programs that protect against GBV, and sharing effective practices to bring awareness to GBV in local communities.218 Support to Life’s efforts demonstrated a closed loop development project, meaning that the original trainees who benefited from the project were enabled to go out and train their own communities.219 Refugee women were kept at the heart of Support to Life’s project, keeping them at the center of project activities and ensuring project details were built upon already existing community structures and capacities, therefore also creating a support system for these women.220

Photo by Ahmed akacha from Pexels

The first part of the project was choosing 16 volunteer women to be the trainers. All these women had gone through a program of Support to Life before and were all from Syria themselves.221 These women were then trained for two days on the legal frameworks on SGBV in Turkey, confidentiality of participants, and how to contact public services.222 The next stage of the project consisted of each volunteer to be assigned to an average of 84 participants, with a total of 1276 participants.223 93% of these participants were over the age of 18 and were all female refugees from Syria.224 Meetings were held with 5-7 participants at a time to make these women aware of available protection services, justice services, and good practices regarding the prevention and healing of GBV.225 Their programs help enable women to understand how to stop the cycle of GBV and receive justice. Within their volunteer-led training sessions, the five topics of rights of temporary protection, marriage-related rights, rights related to termination of marriage, sexual rights and violence-related rights were discussed.226 In the final stage, Support to Life collaborated with local governments, community organizations, and NGOs to link the volunteers and participants with local organizations to continue and expand their trainings.227

Impact

As a result of the Support to Life’s initial project, 16 female refugees were educated on gender awareness, GBV, rights and services within Turkey, civil matters, and facilitation skills through the trainings and civil engagement activities provided.228 1,276 refugee women in Turkey were educated through these volunteer-led meetings.229 70% of these women reported an elevated understanding of women’s rights and services available related to sexual and gender-based violence.230 Support to Life also created a “lessons learned report” which was read and validated, along with details and results of the civil engagement project. This was done in a meeting consisting of the project team, volunteer women, local government officials, community organizations, and international NGOs in order to devise sustainable impact where refugee women would be able to access services independently.231 Rates of access to women’s justice and protection services increased, trainings inspired an enhanced desire to learn more as they trained fellow refugee women, and more safe spaces for facilitated communication were established among women.232 Interviews from participants showed themes of individuals recognizing patterns of abuse in their lives and their vocal commitment to act with the new knowledge they learned next time an incident of GBV happens to them.233 Another long term impact from Support to Life’s project was the psycho-social support it provided for refugee women, increasing their sense of security within their new host country and aiding in the growth of their socio-psychological development and healing.234 After Support to Life performed measurement and evaluation activities of the project, they found that 71.8% of participants in a conducted survey felt they had gained a better awareness of women’s rights and a better knowledge and competence about access to justice services specific to the SGBV.235 Support to Life likened this to a 71.8% success rate in regard to their project objective to “inform women of their peers who are not easy to reach, to provide them with information on access to protection services needed, and to provide them with access to these services.”236

Gaps

Support to Life was faced with challenges surrounding difficulty engaging women with busy lives, lack of gender awareness, skepticism, and community opposition.237 Unfortunately, this caused some refugee women to leave the projects due to fears originating in social stigma and rejection, the same which can arise from GBV itself.238 There is also little research done to show if their intervention actually led to reduced GBV for these refugee women. However, this project was completed three years ago, meaning there may not be sufficient time to measure long term impact.

Preferred Citation: Cole, Genevieve and Harriet Huang. “Violence Against Refugee Women in the MENA Region.” Ballard Brief. March 2022. www.ballardbrief.byu.edu.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints