Illiteracy Among Adults in the United States

By Chloe Haderlie and Alyssa Clark

Published Fall 2017

Special thanks to Marissa Getts for editing and research contributions

+ Summary

Illiteracy affects a person's ability to participate in and contribute to the world around them fully. About 18% of the US adult population is functionally illiterate. Hispanics, older people, and incarcerated people are more likely to be low literate than other US adults. Major factors influencing literacy development include education, socioeconomic status, learning English as a second language, learning disabilities, and crime. Many of these causes and consequences of illiteracy are intersecting and cyclical. Additionally, illiteracy is perpetuated from parent to child and is likely to lead to higher chances of unemployment and poverty. Adult literacy programs with a developed curriculum and personalized instruction are the most effective ways to improve literacy. In order to prevent and treat illiteracy in the United States, collaboration between researchers, nonprofits, governments, and public schools will be necessary.

+ Key Takeaways

+ Key Terms

Dysgraphia–“Impairment of handwriting ability that is characterized chiefly by very poor or often illegible writing or writing that takes an unusually long time and great effort to complete. When present in children, dysgraphia is classified as a learning disability. When it occurs as an acquired condition in adults, it is typically the result of damage to the brain (as from stroke or trauma).”1

Illiteracy–The inability to read or write.

Limited English Proficient (LEP)–”Individuals who do not speak English as their primary language and who have a limited ability to read, speak, write, or understand English can be limited English proficient, or LEP.”3

Literacy–Understanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2

Low Literacy (also known as Functional Illiteracy)–The ability to read relatively short texts and understand basic vocabulary but the inability to comprehend advanced texts and vocabulary. This definition corresponds with having a score of level one or lower on the PIAAC literacy evaluation.4

Context

The ability to read is an important skill for people to develop because it reduces the risk of poverty, increases employability, increases social inclusion, and leads to a healthy life.5 If a person cannot read or comprehend what they is reading, their ability to contribute to and participate in society is significantly limited. Many people think of literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 as the ability to read and illiteracyThe inability to read or write. as the complete inability to read. Low literacyThe ability to read relatively short texts and understand basic vocabulary but the inability to comprehend advanced texts and vocabulary. This definition corresponds with having a score of level one or lower on the PIAAC literacy evaluation.4, also known as functional literacy, is of equal importance. 6 A functionally illiterate person can read read relatively short texts and understand simple vocabulary; however, he may struggle with basic literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 tasks such as reading and understanding menus, medical prescriptions, news articles, or children’s books.7 In 2014, reports indicated that 18% of US adults (approximately 57.4 million people) are functionally illiterate. Other sources indicate that up to 90 million US adults lack basic literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2.8

IlliteracyThe inability to read or write. has many negative impacts on individuals and society. Overall, low-literate adults participate less in the labor force, earn less, and are less likely to read to their children, which may stunt their children’s literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 development.9 As illiteracyThe inability to read or write. may pass from parent to child, subsequent generations will likely suffer from unemployment and poverty.

Other negative consequences of illiteracyThe inability to read or write. include crime, poor health, low academic performance, and slow economic growth. Estimates show that these negative social and economic outcomes cost the United States $362.49 billion annually.10 Countries with higher literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 rates have more national productivity, better health, and greater equality than nations with lower literacy rates.11

The shame associated with learning disabilities (LDs) and low literacyThe ability to read relatively short texts and understand basic vocabulary but the inability to comprehend advanced texts and vocabulary. This definition corresponds with having a score of level one or lower on the PIAAC literacy evaluation.4 sometimes prevents individuals from seeking the help they need to become literate, perpetuating the issue throughout an individual’s lifetime. Many low-literate individuals hide their illiteracyThe inability to read or write. from their employers, associates, children, and even spouses. Studies show that 53% of low-literate adults have never told their children about their reading inability.12 Feelings of shame and inadequacy may lead to low self-esteem and poor mental health. These feelings create an emotional barrier, further inhibiting illiterate adults from seeking help in learning to read.13

Literacy Development

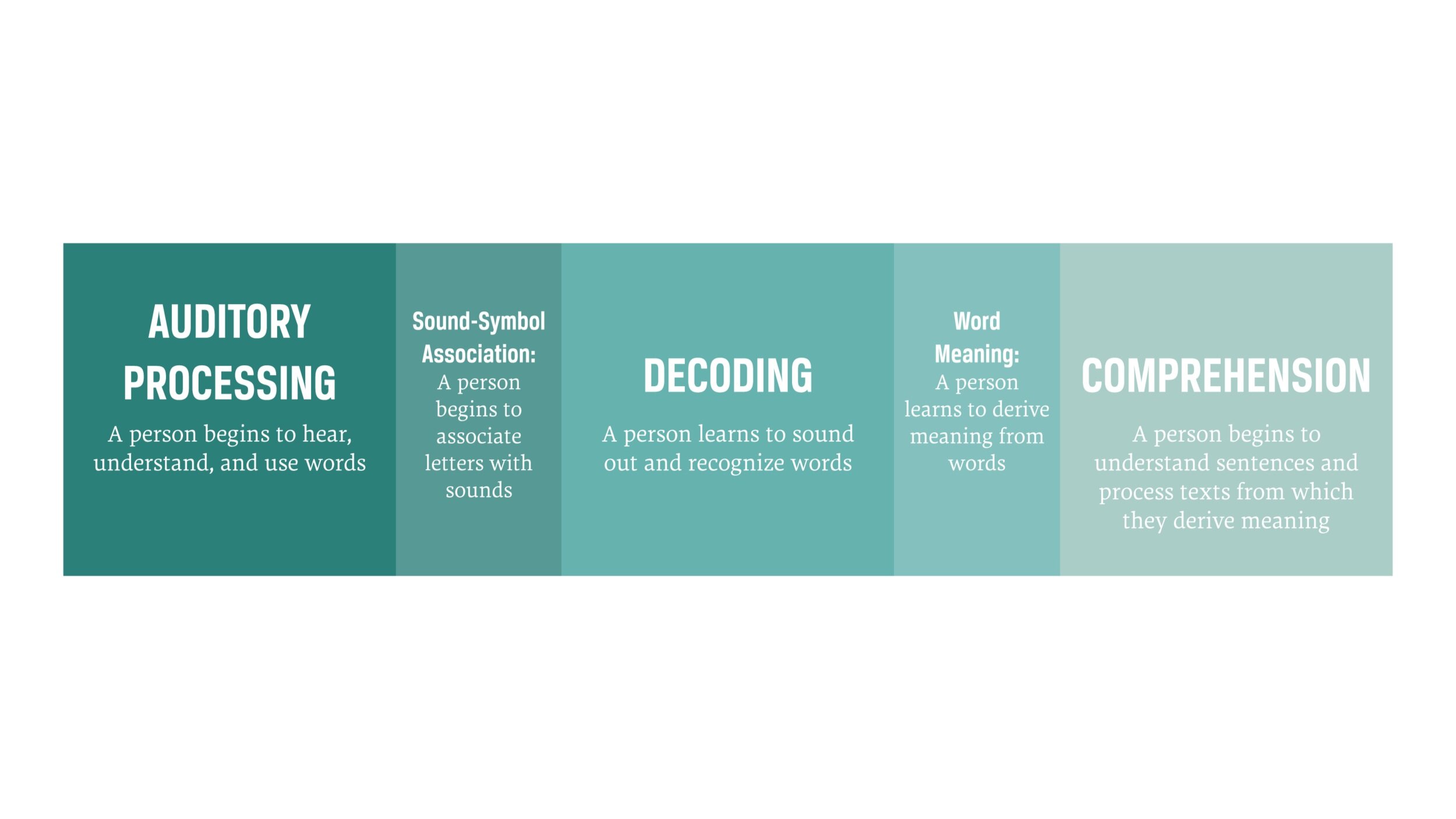

Learning to read combines three primary cognitive skills: auditory processing, decoding, and comprehension.

- Auditory Processing begins in childhood when a person starts to hear, understand, and use words.

- Decoding occurs as a person learns to sound out or recognize written words.

- Comprehension happens when the reader derives meaning from words, sentences, and entire texts once the content has been decoded.

Both decoding and comprehension develop through speaking and reading. An individual’s literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 skills are heavily influenced by the language abilities and vocabulary of the people closest to the individual (for example, family members, neighbors, and friends).14, 15 Most people learn to read when they are young, and their comprehension increases as they grow up because they are exposed to more words and ideas through school and life experience. Simply put, low literacyThe ability to read relatively short texts and understand basic vocabulary but the inability to comprehend advanced texts and vocabulary. This definition corresponds with having a score of level one or lower on the PIAAC literacy evaluation.4 is caused by a failure to develop these three main reading and comprehension skills adequately.

Demographics

IlliteracyThe inability to read or write. tends to affect Hispanics, older people, and the incarcerated more than other US adults. Hispanics have the highest percentage of low literacy scores, followed by Blacks, Others, and Whites.16 Racial segregation and the number of non-native English speakers among minorities may correlate with low literacyThe ability to read relatively short texts and understand basic vocabulary but the inability to comprehend advanced texts and vocabulary. This definition corresponds with having a score of level one or lower on the PIAAC literacy evaluation.4 in those groups. Older adults in all racial groups are also more likely to be low literate: about 28% of 66—74-year-olds have the highest percentage of low literacy.17 This pattern may be due to increased access to education over time. As educational opportunities have expanded in the United States, younger generations have benefitted from the changes while older age groups have not. Another reason may be that some older adults do not continue to practice their literacy skills after completing their formal education. Finally, low-literate adults are overrepresented in US prisons (different reports indicate that 29%—60% of incarcerated adults are low literate).18, 19

Results of a nationally representative survey from 2003,20 in combination with US Census data from 2000,21 show correlations between illiteracyThe inability to read or write., low income, low levels of education, and unemployment. All of these issues are concentrated in Southern states and urban locations. Possible explanations for the intersectionality of race, poverty, age, and incarceration will be outlined in the following sections.

Contributing Factors and Consequences

Note: Many of the contributing factors to illiteracyThe inability to read or write. are both causes and consequences and will be addressed together.

Education

A quality education provides foundational literacy skills that contribute to adult literacy. When education is limited, literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 is limited. Among developed countries, the United States ranks 24 out of 35 countries in reading scores.22 Additionally, literacy rates have not improved over time, revealing that US schools continue to underperform. Socioeconomic and racial inequality in neighborhoods are correlated. Both inequalities lead to educational inequality. The intersection of these three inequalities is most heavily concentrated in urban areas.

Socioeconomic and racial inequality are interconnected. Minority and low-income students tend to underperform on tests and have low literacy levels. When a student living in poverty is also from a racial minority group, then he is even more likely to be low literate.23 In many of the largest cities in the United States, a majority of students are from minority groups, and three-quarters of students are poor.24 In cities where poverty and racial inequality intersect, students in 8th grade perform 8–10% worse than students in rural, town, and suburban public schools on reading achievement tests.25 Though many people mistakenly think that racial segregation has ended, research shows that US schools are currently re-segregating by race and income. These trends mainly affect Hispanic and black students.26

Socioeconomic Inequality in Education

Quality of education depends on equality in schools.27 Because public schools are primarily funded by local property taxes, living in a low-income area generally means attending a low-income school.28 This structure leads to a lack of funding, resources, and fewer teachers in poor schools. These outcomes, in turn, affect a child’s future educational attainment and income.29 Schools in low-income areas have less parental support.30 Additionally, students from low-income backgrounds are less likely to have adult mentors with college experience.31 The resulting inequality in schools leads to lower average literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 and academic performance in poor schools.

When schools do not have adequate funding, they are forced to take at least some of the following measures:

- Employ fewer teachers and increase class size

- Hire underqualified teachers

- Cut funding for necessary instructional resources such as books and computers

Employing enough skilled teachers is essential because the quality of instruction plays an vital role in literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 development. The larger the class size, the less one-on-one instruction students receive. The disparity increases the chances that students will graduate with poor reading skills and be low literate as adults. Teacher shortages tend to most significantly affect low-income schools with high concentrations of minority populations, perpetuating racial and economic inequalities.32

Racial Inequality in Education

Racial inequality in education affects student success and literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 development. Academic achievement is measured by student performance on standardized tests. Results from these tests show that black and Hispanic students perform worse than white students.33 Research indicates that this inequality in schools continues to affect achievement levels; black students are twice as likely to underperform as white students.34 Experts suggest that minority-group students may underperform because their teachers and peers tend to have lower expectations for them.35 Research projects that eliminating racial segregation in schools would close over 10% of the achievement gap for black and white students.36

Racial discrimination in schools contributes to minorities having lower literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 levels. Racial segregation in schools was legal during the first half of the 1900s. However, in 1954, Brown v. Board of Education abolished racial segregation in public schools because segregation violated equal rights. Although this change legally granted black people and white people equal access to education, segregation persisted in practice.37 When schools and neighborhoods became legally integrated, many white people moved away from their newly integrated neighborhoods. This “white flight” left behind schools that continue to be poor and segregated to this day.38 As a result, some neighborhoods now have high concentrations of minority groups and low-income families.

As mentioned previously, older adults are more likely to be low literate. Historical discrimination is one possible explanation for this tendency. Changes in access to education during the second half of the 1900s, partially spurred by the response to racial discrimination, may help explain why older adults, especially older adults from racial minority groups, tend to have lower literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 levels. Many older adults experienced these changes in access to education and societal attitudes during their lifetimes and were thus directly influenced by them.

Poverty

Poverty and low literacy have a cyclical relationship. Low-literate adults are more likely to live in poverty than high-literate adults; about 43% of low-literate adults live in poverty, compared to only 5% of people at the highest literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 level.39 Studies show that literacy levels vary more with socioeconomic status than ethnicity or gender.40

Poverty limits literacy development at all stages (see Figure 1). Research indicates that a mother’s education is the most important indicator of her child’s future educational achievement.41 If a child’s parent is illiterate, the parent will not be able to teach her child to read, increasing the likelihood that a child will also be illiterate. Because language first develops orally, what a child hears at home will impact his or her future literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 abilities. Approximately 86%—98% of a child’s vocabulary comes from their parent’s vocabulary. The number and variety of words heard at home differ between wealthy and poor households. By age three, children in high-income homes have heard 30 million more words than children in low-income homes, significantly influencing the children’s future literacy development.42

Additionally, low-income students are more likely than their wealthier peers to do the following:

- Develop reading and language acquisition skills later43

- Not attend preschool44

- Attend poorly funded schools45

- Read less and have fewer books in the home46

- Struggle to regulate emotions in social situations47

- Develop learning challenges in attention, memory, and thinking48

- Stop attending school to contribute to their family’s income49

Low literacyThe ability to read relatively short texts and understand basic vocabulary but the inability to comprehend advanced texts and vocabulary. This definition corresponds with having a score of level one or lower on the PIAAC literacy evaluation.4 limits employment opportunities, leading to increased poverty rates and future poverty for the individuals affected. Many low-skill jobs are outsourced or may be replaced by technology, leaving many illiterate adults unemployed.50 Approximately 24% of unemployed people in the United States are low literate, with higher percentages of low literacy among those with less than a high school education.51 These people have a difficult time finding work because they are unqualified for many jobs that require reading skills.52

Non-Native English Speakers

Many non-native English speakers, such as immigrants and refugees, have low English literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 levels. While some of these people may be literate in their native tongue, they are considered illiterate in English. Approximately 8% (25.1 million people) of the US population ages 5 and older are Limited English Proficient (LEP)”Individuals who do not speak English as their primary language and who have a limited ability to read, speak, write, or understand English can be limited English proficient, or LEP.”3.53 Sixty-four percent of adult immigrants perform at low literacyThe ability to read relatively short texts and understand basic vocabulary but the inability to comprehend advanced texts and vocabulary. This definition corresponds with having a score of level one or lower on the PIAAC literacy evaluation.4 levels, compared to 14% of native-born Americans.54 The majority of LEP adults speak Spanish as their first language. Other large portions of the LEP population speak Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean, and Tagalog.55

The LEP population in the United States tends to live in poverty and to be less educated than the general population.56 Many LEP adults have low-skill, low-wage jobs in the construction, agriculture, and service sectors that usually do not require English language skills. In 2013, 25% of LEP individuals lived below the official federal poverty line (about $24,000 for a family of four in 2013.57,58 Seventy-five percent of the LEP population is between ages 18 and 64.59 Though many adult immigrants and refugees seek out English education in order to become literate, developing reading proficiency takes time. Finding time to learn is especially challenging for adults who do not have the same structured learning opportunities as children have through the public education system. Even if children of LEPs are taught English in the public school system, the children still may be vulnerable to challenges in literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 development. These challenges include living in poor neighborhoods, attending low-income or racially segregated schools with limited resources, and growing up in a home with parents who cannot teach them to read in English.60 Although attending school does not guarantee English literacy, children have more resources available to them than do adults.

Learning Disabilities

Learning disabilities (LDs) are correlated with poor reading skills and are a contributing factor to low literacy in the United States. Research indicates that learning disabilities may be caused by genetics, prenatal exposure to toxins (such as lead, drugs, or alcohol), and adverse childhood experiences.61 The learning disabilities that affect reading abilities most are dysgraphia“Impairment of handwriting ability that is characterized chiefly by very poor or often illegible writing or writing that takes an unusually long time and great effort to complete. When present in children, dysgraphia is classified as a learning disability. When it occurs as an acquired condition in adults, it is typically the result of damage to the brain (as from stroke or trauma).”1, auditory processing deficit, dyslexia, and ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder).62 Learning disabilities may affect literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 at all stages but typically have a greater impact on comprehension. People with learning disabilities can often read aloud without difficulty but may not comprehend or remember what they read.63

About 4.6 million Americans report having a learning disability; however actual numbers are likely higher because of underdiagnosis and underreporting due to the stigmas associated with learning disabilities.64,65 Reported learning disabilities are higher among those living in poverty than those living above poverty. They are also higher among school-aged children than adults (see figure XXX);66 however, it is estimated that 60% of adults who struggle with literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 have undiagnosed or untreated learning disabilities.67 Diagnosis also tends to be higher among low-income, minority, and ELL (English-Language Learning) children, partly due to stereotypes and bias.68 While approximately 1 in 5 children have a learning disability, only 1 in 16 receives an individualized education plan (IEP) to help the child learn with his or her disability in public schools. This imbalance may be because 70% of teachers feel that they do not have the resources to help students with learning disabilities.69 One common misconception about people with learning disabilities is that they are less intelligent or capable; nearly one in five parents believe that children with LDs are less intelligent.70 In reality, rather than being less intelligent, LD children have a skill deficit in reading. Awareness of this misconception is important in helping these people to learn more effectively and with confidence.71

Crime

Low literacyThe ability to read relatively short texts and understand basic vocabulary but the inability to comprehend advanced texts and vocabulary. This definition corresponds with having a score of level one or lower on the PIAAC literacy evaluation.4 does not cause criminal behavior, but many contributing factors of low literacy also contribute to criminal behavior, which may lead to incarceration. Contributing factors to both low literacy and criminal behavior include racial inequality, poverty, and education.72 These factors make individuals more vulnerable to both crime and illiteracyThe inability to read or write..

Estimates of the percentage of incarcerated adults who are low literate range between 29% and 60%.73,74 A 2007 federal and state prison literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 report shows that 69% of inmates are from a racial minority, and 26% of inmates did not graduate high school or obtain a GED certification. Black and Hispanic inmates had lower literacy levels than their white peers.75

Upon release from prison, former convicts are more likely than non-convicts to work at a low-wage job, remain uneducated, or be unemployed because of their criminal record or racial discrimination.76 These factors increase the chances that they will commit another crime or live in poverty.77 Some estimate that two-thirds of children who are not reading at their grade level by the fourth grade will end up in jail or on welfare.78 Additionally, children who grow up with a parent in prison are more likely to face developmental challenges and adverse childhood experiences than children who grow up with neither parent incarcerated.79, 80 Without parental support and guidance, the children of the incarcerated are also less likely to learn to read in the home. Again, these challenges affect blacks, Hispanics, and low-income families disproportionately; for example, a black child is nearly twice as likely as a white child to have a parent in prison (14% of black children have a parent in prison).81

Intersecting Factors

The factors that contribute to low literacy intersect in many ways. If a person faces one of the challenges to literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 development described above, he or she is likely to face more than one because these challenges are connected. Some examples include the following:

- Poverty often overlaps with discrimination toward racial minorities and opportunities afforded non-native English speakers. It also contributes to these populations attending low-income schools.

- Incarceration increases a person’s chance of poverty because of limited employment opportunities post-incarceration. Incarceration rates are also higher among minority groups, especially black men with low levels of education.

- Resegregation by race and income leads to high concentrations of poverty and crime in certain neighborhoods. These high poverty and crime rates negatively affect the education system and increase the likelihood of adverse childhood experiences. Adverse childhood experiences limit cognitive development and increase future crime, continuing the cycle.82, 83, 84

- Children from racial minority or low-income families are overrepresented in special education at schools with limited resources to help them. Being placed in special needs programs increases the chances of those children being unemployed or incarcerated in their lifetime.85

These examples show the complexity of societal failures that create significant barriers for some groups of people to develop adequate literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 skills. These contributing factors tend to be intergenerational, creating vicious cycles that many cannot escape.

Practices

Adult illiteracyThe inability to read or write. cannot be eliminated unless gaps in childhood literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 are filled. If a person is effectively taught to decode and comprehend as a child, she will be more literate as an adult. Preventing illiteracyThe inability to read or write. requires coordination and efforts from families, nonprofits, schools, and federal and state governments. Massachusetts appears to be a leader in successful public education in the United States with a high school dropout rate of only 2% and the nation’s highest math and reading scores.86 As a state, only 10% of the adult population is considered low literate (compared to the national average of 18%).87 Potential explanations of the success include increased funding to low-income schools and districts, with a focus on hiring more teachers and providing more educational resources in the classroom. Additionally, Massachusetts has increased awareness and understanding about social-emotional education and the trauma associated with poverty and unstable family situations.88

An in-depth discussion of preventative practices is beyond the scope of this briefing. Nevertheless, we recognize that a combination of preventative and treatment practices will create a more comprehensive solution to this issue. The following sections focus on treatment-oriented solutions that aid adults who are already illiterate.

Donating Books

Donating books is a widespread yet ineffective practice implemented by many organizations. The objective of donating books is to provide populations that have limited access to reading materials with the resources they need to practice reading. These donations are primarily given to low-income elementary schools and low-income children so that they can have books to read over the summer months.89 Most organizations appear to focus on donating books to children.

Impact

Millions of books are donated to schools and individuals each year. However, there is no convincing data to suggest that these donations actually increase adult literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2.

Gaps

Donations are almost always provided to children rather than adults, and therefore do not contribute to increasing adult literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2. If books are donated to families, the topics of the books are generally relevant to children and may be uninteresting to adults, causing the books to go unread.90 Ultimately, simply providing books to low-literate people will not improve literacy competence unless combined with other practices, such as effective instruction.

Collaboration with Existing Organizations and Companies

Partnerships between existing social service organizations and companies expand the reach of literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 education. For example, a nonprofit may partner with a business or another social service organization in order to reach a specific demographic, institute new programs, and share literacy instruction strategies.

ProLiteracy is the primary international organization involved in partnering. Its main goal is to add adult literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 services to existing organizations, such as libraries. ProLiteracy trains and certifies literacy instructors who teach a standard curriculum.91 In 2016, ProLiteracy began partnering with nonprofit organizations in Salt Lake City, Utah, to provide services for English language learners. This partnership is an interdisciplinary approach in which instructors simultaneously teach literacy and basic workforce skills. The curriculum is more customized to the needs of the population it serves and prepares immigrants and refugees for better employment while increasing their ability to read.92

Creating partnerships with companies to educate employees also expands literacy programs' reach. In 2013, Alfalit, a nonprofit based in Florida that provides literacy training in the US and internationally, partnered with a Florida-based company, Costa Farms. Costa Farms’ employees were primarily immigrants who had never had the opportunity to learn to read or write in their country or language of origin. Alfalit provides literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 training in the employees’ native language.93 Through this type of partnership, organizations gain access to more of the illiterate portion of the population, and employers also benefit by gaining employees who are more highly trained and better educated.

The National Literacy Directory is also a key player in forming collaborative efforts and enabling partnerships. This directory functions as a comprehensive database and connection point for students, volunteers, and organizations. It contains descriptions and contact information for local literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 organizations in the United States so that volunteers and students can find a program that matches their needs.94

Impact

Social service organizations see collaboration as a means to access greater funds and improve solutions.95 Additionally, collaboration between existing organizations and companies can open unique doors to access specific portions of the illiterate population. Data from individual organizations does not emphasize the impact of collaboration between organizations. However, output and outcome data are available for individual organizations that collaborate. From 2015 to 2016, ProLiteracy reached 222,397 students and certified 85,490 instructors. However, of the 244,106 students reached in 2014—2015, only 70,000 advanced at least one level in the curriculum (28% advancement rate).96 Of those who improve their literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2, 16,300 students reported finding better employment.97 Alfalit reports that after students graduate from the program, they can read and write at a third-grade level in their native language.98 Over 200 people have now graduated from the Alfalit program.99

The National Literacy Directory facilitates collaboration with more than 7,000 literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 education agencies and over 50,000 volunteers and students. These organizations and individuals have used the directory to connect with agencies that meet their needs.100 The available data does not show how many students improve their literacy due to these connections.

Gaps

Partnerships and collaboration are not always effective. In some cases, collaborative efforts are economically inefficient or may limit the organizations’ individual objectives, yielding suboptimal results.101 Because of the lack of impact data from key partner organizations, there is no reliable assessment of collaborative effectiveness in literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 training. However, it is important to be aware of the potential costs of collaboration.

Additionally, the National Literacy Directory is not a direct solution to adult illiteracyThe inability to read or write. because it does not offer specific services to the illiterate population. Rather, it plays an important intermediary role by facilitating access to improved services and information for students, volunteers, and organizations. One potential gap is the accessibility of information to low-literate adults who may struggle to navigate the written information on the database.

Prison Literacy Programs

Providing education to adults in prison can increase adult literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2. Many prisons offer some form of education program for their inmates through prison-led initiatives or collaboration with nonprofits, community volunteers, churches, or colleges. These programs provide education at various levels, including the following:

- Adult primary education: instruction in basic arithmetic, reading, writing, and English as a second language

- Adult secondary education: high-school or high-school-equivalency-level education that prepares students to earn their GED certificate

- Vocational education or career technical education (CTE): skill training for employment in specific jobs or industries

- Postsecondary education: instruction at the college level, which helps a student work towards a two- or four-year degree102

These programs exist nationwide; more than 28 states have college education programs in prison, and more than 100 prisons have academic and career programs.103

Impact

Extensive research has been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of prison education programs in general, but there is less data about prison literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 programs specifically. Reliable research indicates that providing education to prisoners increases their academic achievement, reduces their chance of reoffending by 43%, and increases their chance of obtaining better employment when released by 13%.104 This research also indicates that investing tax dollars in education programs has a 400% return when compared to the costs of re-incarceration.105

Gaps

There is a lack of evaluation of individual literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 programs. Because of this lack of data, it is unclear which literacy programs are most effective. Experts suggest that funds be allocated to researching and evaluating programs that use new and potentially more impactful instructional models.106

One of the major gaps in prison education programs is obtaining sufficient funding. Some funding comes through taxes; others come through philanthropic donors such as nonprofits, churches, and individuals.107 Lack of funding also results in a lack of access to literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 programs. While more than 28 states have implemented these programs in prisons, many others have not. Lack of funding contributes to this disparity.

Online Resources and Technological Tools

A method that has emerged alongside the development of technology is the use of online education tools. This is done through a variety of online resources, such as websites and phone apps. Some organizations are using technology to specifically help people with learning disabilities who may struggle to learn in traditional ways.108 Other organizations are working to increase access to educational tools through technology such as tablets and e-books.109

The use of technology to help students and adults with learning disabilities has been particularly innovative. By providing text-to-speech, speech-to-text, and organizational tools, students with learning disabilities have been able to improve their decoding, comprehension, and writing skills.110, 111 Similar tools aimed at vocabulary development are used for ELL students.112 These practices are being implemented in classrooms and adult literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 programs.

Given the current trend, technology-heavy methods of instruction will likely continue to be employed for literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 instruction. If paired with empirically proven methods of literacy instruction and an initiative to foster a culture of reading in US homes, these methods may improve literacy.

Impact

No empirical evidence suggests that online tools and phone apps improve literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2. Some speech professionals are skeptical about how effective these tools are.113 While there is no data-backed evidence to support this practice, it has some benefits. Using technology makes educational resources widely accessible. It is also cost-effective because most educational apps can be obtained for free. Moreover, studies show that adult literacy instruction through technology increased the subjects’ ability to navigate websites, analyze media, and evaluate online texts.114

Gaps

A major gap in this practice is the lack of impact data available. Because the use of these tools is both new and likely to expand, research must be conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of online and electronic programs and tools. Another disadvantage of online tools is that low-income populations, who are most vulnerable to illiteracyThe inability to read or write., may have less access to technology and the Internet. Although access to the Internet is increasing, 48% of households that make less than $25,000 per year still lack an online connection.115

Additionally, some critics believe that literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 is an instilled value and that instruction via technology diminishes the reading culture in American homes.116

English as a Second Language (ESL) Programs

To address the needs of a growing non-native English speaking population in the United States, many groups are developing ESL programs to improve English speaking and literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2. These programs are available through the federal government, local community centers, libraries, nonprofits, and online resources. The classes emphasize speaking, reading, and writing English–important parts of developing decoding and comprehension skills for literacy.117 Program members practice these skills through speaking in conversation groups, reading books, and participating in other activities.118

Impact

ESL programs vary in their reported success rates for teaching students English and improving adult literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2. Because there is no centralized standard curriculum for ESL programs, there is no comprehensive data to assess the impact of ESL classes on literacy development. However, learning to speak and read English has many benefits. Socially and culturally, English-speaking and reading abilities increase people’s understanding of the world around them. Additionally, research found that Hispanic immigrants who become fluent and literate in English have higher income and employment levels.119

Gaps

An assessment of ESL programs, conducted using focus groups in Santa Clara County, California, found several gaps in ESL programs. The assessment found several shortcomings in program accessibility and effectiveness. These gaps include the following:

- Lack of coordination between ESL providers

- Limited access to information about programs for students

- Few beginner-level classes

- Inapplicable curriculum for students, especially for those who are professionals

- Issues with scheduling classes that ELLs can attend (typically better in the evenings or on weekends)

- Lack of public transportation to classes

- No organized childcare where classes are offered

- Not enough cultural awareness and sensitivity in classrooms120

- Student absenteeism

- Inconsistent, repetitive, and unstructured programs121

Adult Literacy Classes

The most effective solution to improving adult literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 is adult literacy classes. Adult literacy classes can be found at libraries, community centers, schools, and independent literacy centers throughout the United States. These classes aim to improve decoding skills, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension.122 Because the classes operate at the local or state level, there are no specific program standards nationwide. However, defining characteristics of adult literacy classes include the following:

- The use of texts that are at the appropriate reading level and content level for adults

- Practical and real-world application activities to ensure adults will practice their skills outside of class

- Individualized and adaptable instruction to meet the unique needs of students123

Evidence-based and systematic instruction, when implemented effectively, can increase literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2.124 Curriculum and instruction are always most impactful when personalized to a student’s individual needs and learning level. Additionally, programs that incorporate systematic and engaging learning have been proven to create the best results.125 Putting learning into context can only be done through personalized instruction. Additionally, for English Language , the curriculum should support learning in English and their native language.126

Impact

Randomized control trials conducted nationwide have found that implementing instructional programs in adult literacyUnderstanding, evaluating, using, and engaging with written text to participate in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.2 classes effectively improves adult literacy. The studies also emphasize that the effectiveness of curriculum and instruction is dependent on student attendance.127, 128

Gaps

- Lack of consistent and reliable data to show which programs are the most effective.129

- Challenges of creating and administering reliable tests to determine student progress.130

- Costs of publication and distribution of materials.

- Producing materials at an appropriate reading level for adult students.

- Accessibility to classes for the most vulnerable populations.

- Lack of programs focused on helping adults with learning disabilities, especially minority and low-income populations.

- Instructors not being properly trained or committed to the curriculum, causing it to be ineffective.131

- Student absence or non-participation in classes.132

Preferred Citation: Haderlie, Chloe and Alyssa Clark. “Illiteracy Among Adults in the US.” Ballard Brief. November 2017. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints