Barriers to Career Advancement Among Skilled Immigrants in the US

Photo by Sora Shimazaki

By Cassie Arnita

Published Fall 2022

Special thanks to Robyn Mortensen for editing and research contributions.

Summary+

Over 2 million highly-skilled immigrants in the US are either underemployed or unemployed due to barriers to career advancement. Barriers to career advancement include, but are not limited to, legal status, the process of transferring credentials, the license and certification process, lack of employer recognition, lack of cultural literacy, and the language barrier. Because of these barriers, immigrants face many challenges, such as retraining, paying high fees for courses or tests, limited course options due to a language barrier, and lacking knowledge of US job application processes. These challenges often prevent immigrants from working high-skilled jobs in the workplace. When immigrants cannot utilize their workplace skills, it is known as brain waste, which results in skill underutilization. Immigrants who experience brain waste contribute to millions of dollars lost annually in revenue and taxes, have poor mental health, and struggle to support families financially due to being underemployed or unemployed. Career counseling and accessible or cheap training or retraining are the best practices for helping skilled immigrants to continue their careers in the US.

Key Takeaways+

- Over 2 million highly-skilled immigrants in the US experience underemployment and unemployment.

- Twenty-five percent of highly-skilled immigrants with foreign degrees experience skill underutilization, compared to 18% of US-born highly-skilled workers.

- Legal status, the process of transferring credentials, the license and certification process, lack of employer recognition, cultural literacy, and the language barrier are the most prominent barriers to immigrants continuing their careers in the US.

- Skilled immigrants who experience brain waste experience poor mental health, struggle to support their families financially and contribute to millions of dollars lost for the US each year because of the barriers to career advancement.

- Career counseling and accessible, cheap training or retraining have proven to have the best influence on helping skilled immigrants continue their careers in the US.

Key Terms+

Brain waste—When highly-skilled immigrants can not utilize their skills in the workplace, despite their qualifications. Brain waste results in underemployment and unemployment.1

High-skilled jobs—For the purpose of this brief: jobs that require a bachelor’s degree or higher.2

Highly-skilled immigrants—Immigrants with a foreign college degree or higher, typically possessing special skills or knowledge for a certain profession.3

Low Skill or Survival Jobs—Jobs that require workers to have no more than a high school education and no more than 1 year of work experience.4

Social capital—Social capital is the networks of relationships and shared values among people in a society.5

Underemployment—Describes highly-skilled immigrants who are working in low-skilled jobs.6

Unemployment—Describes immigrants seeking employment but being unable to find work.7

Context

Q: What is skill underutilization, and how does it affect skilled immigrants in the US?

A: Skill underutilization is when workers cannot utilize their workplace skills despite their qualifications. When skilled workers cannot apply themselves in the workplace, they experience underemploymentDescribes highly-skilled immigrants who are working in low-skilled jobs.6 and unemploymentDescribes immigrants seeking employment but being unable to find work.7>. Barriers to career advancement are events or conditions which make career progress difficult for an individual and can lead to skill underutilization. The barriers discussed in this brief include legal status, the process of transferring credentials, the license and certification process, lack of employer recognition, lack of cultural literacy, and the language barrier. Over 2 million highly-skilled immigrantsImmigrants with a foreign college degree or higher, typically possessing special skills or knowledge for a certain profession.3 in the US face barriers to career advancement following immigration and, consequently, experience skill underutilization.8 Highly-skilled immigrants are immigrants with a foreign college degree or higher or who possess special skills or knowledge for a certain profession.9

Rather than working in their trained field, skilled immigrants often end up working low-skilled survival jobsJobs that require workers to have no more than a high school education and no more than 1 year of work experience.4 where they can not utilize their skills in the workplace, a process known as brain wasteWhen highly-skilled immigrants can not utilize their skills in the workplace, despite their qualifications. Brain waste results in underemployment and unemployment.1.10 As a result, some immigrants never re-enter their profession, while others spend excessive time and money retraining and transferring credentials to continue their careers.11 The number of immigrants experiencing skill underutilization is only growing as more foreign-educated immigrants come to the US each year.12 Between 2000–2010, the college-educated immigrant population in the US increased by 57%, and from 2010–2018, it increased by 38%.13 Conversely, the college-educated native-born population increased at a slower rate, with a 26% increase from 2000–2010 and a 24% increase from 2010–2018.14 The table below shows the percentage of skilled immigrants with bachelor’s and postgraduate degrees in the US over time. Although we do not know how the rate of immigrant skill underutilization is changing, many researchers assume that the number is growing due to the growing number of skilled immigrants in the US each year.15

Q: Where are skilled immigrants coming from, and why are they moving to the US?

A: The table below shows the percentage of skilled immigrants from each country or area. Although most skilled immigrants come from Asia, immigrants from Mexico, the Caribbean, Africa, South America, and the Philippines are most likely to experience skill underutilization. For example, 47% of Mexican immigrants, 44% of Caribbean immigrants, 34% of African immigrants, 35% of South American immigrants, and 35% of Filipino immigrants experience skill underutilization.16 According to the US Census Bureau, skilled black immigrants are 54% more likely than white immigrants to experience skill underutilization, and Latino immigrants are 40% more likely to experience skill underutilization.17 In addition, Asian-American and Pacific Islander immigrants are 12% less likely than white immigrants to be underemployed.18 A Harvard study analyzed 55,842 job applications, and researchers found that Latinos experienced the most work discrimination while Asians experienced the least.19 This disparity could be due to ethnic stereotypes. Research has shown that Asians are often perceived as a “model minority” in Western society, portraying them as hardworking and intelligent.20

The reasons why immigrants leave vary depending on the country. Immigrants leave their home countries because of conflict, repressive governance, limited economic opportunities, drought, famine, extreme religious activity, poor sanitation, overpopulation, and lack of jobs.21 According to the UN’s World Migration Report of 2020, the United States has been the primary destination for foreign migrants since 1970.22 In less than 50 years, the number of foreign-born residents of the country has more than quadrupled—from less than 12 million to close to 51 million.23, 24 Better economic opportunities, more jobs, and promises of a better life often pull people to the US. The US has an active economy with a wide array of work opportunities as well as wages that are higher than most countries and have a greater purchasing power.25, 26, 27 The purchasing power index measures the value of a currency expressed in terms of the number of goods or services that one unit of money can buy.28 A higher index means that people can afford more based on the cost of living relative to income.29 The purchasing power index ranges from 5–125. The US is currently ranked 20th in the world, with a purchasing power index of 100.30

The US and Canada are the only countries that have conducted extensive research on barriers to career advancement for skilled immigrants.31 Both countries are top destinations for immigrants, and the barriers to career advancement are similar. Researchers in Canada have found that common barriers to career advancement include a lack of social capitalSocial capital is the networks of relationships and shared values among people in a society.5 and a lack of recognition of foreign credentials.32

Q: Who are the immigrants in the US experiencing skill underutilization?

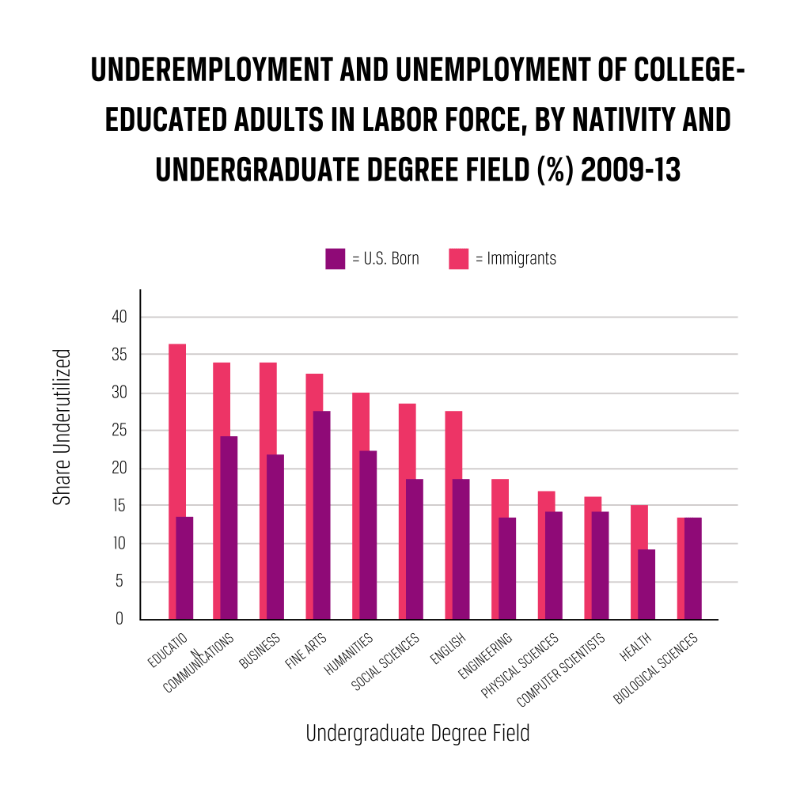

A: Immigrants make up 13.5% of the US population and 17% of the US workforce.33 Forty-five percent of these immigrants are college-educated and considered highly skilled. Highly-skilled immigrantsImmigrants with a foreign college degree or higher, typically possessing special skills or knowledge for a certain profession.3 are immigrants with a foreign college degree or higher, typically possessing special skills or knowledge for a certain profession. In the US, 25% of highly-skilled immigrants experience skill underutilization, while 18% of US-born citizens experience skill underutilization.34 The table below shows that skill underutilization is more common for immigrants than for US-born citizens in almost every educational field.35

While skill underutilization is a problem for immigrants in almost every profession in the US, it is more common in certain fields.36 The table below shows the percentage of skill underutilization for immigrants in various degree fields. In addition, skill underutilization rates are displayed for the immigrants and US-born population. Underutilization for skilled immigrants is most prevalent in education (36%), communications (34%), and business (34%).37

Q: How long has immigrant skill underutilization been happening in the US?

A: In 2008, the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) was the first institution to quantify the extent of skill underutilization among highly-skilled immigrantsImmigrants with a foreign college degree or higher, typically possessing special skills or knowledge for a certain profession.3 in the US.38 Before 2003, no research was conducted to calculate the amount of underemployed and unemployed highly-skilled immigrants in the US. Due to these recent findings, it is not known how long skill underutilization has been happening; however, it was likely before the MPI quantified skill underutilization in 2008.39 It is not known how the rate of immigrant skill underutilization has changed in the US, though some researchers assume that the number is growing due to the increasing number of skilled immigrants in the US.40 Therefore, further research needs to be conducted to know how long immigrant skill underutilization has been occurring in the US.

Q: Where is immigrant skill underutilization happening in the US?

A: California has the highest immigrant underemploymentDescribes highly-skilled immigrants who are working in low-skilled jobs.6 rates, hosting 27% of underutilized immigrants in the US.41 As of 2019, California, Florida, New York, Texas, New Jersey, and Illinois accounted for 61% of underutilized skilled immigrants in the US.42

UnderemploymentDescribes highly-skilled immigrants who are working in low-skilled jobs.6 among highly-skilled immigrantsImmigrants with a foreign college degree or higher, typically possessing special skills or knowledge for a certain profession.3 exceeds the underemployment of US-born citizens in 47 states, suggesting that brain wasteWhen highly-skilled immigrants can not utilize their skills in the workplace, despite their qualifications. Brain waste results in underemployment and unemployment.1 is a national issue.43 Michigan and Ohio have the lowest gaps between underemploymentDescribes highly-skilled immigrants who are working in low-skilled jobs.6 rates of immigrant and US-born college graduates (20% and 21% underemployment among immigrants, respectively).44 Michigan and Ohio have implemented programs to attract and employ highly-skilled immigrants.45

Contributing Factors

Difficulty of Transfer

Legal Status and Skill Underutilization

The legal status of skilled immigrants in the US contributes to skill underutilization because immigrants who do not hold work visas must go through the credential transfer and re-credentialing process. The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), passed in 1952, determines who can enter the United States, who can obtain permanent residency, and who is required to leave the country.46 The INA categorizes residents into 2 categories: US citizens and non-citizens. Non-citizens are those not of the state or nation in which they live and have not yet received full legal status as a citizen.47

Skilled immigrants who enter with a work visa are placed in jobs where they can continue their careers in the US While the US provides 140,000 work visas per year for highly-skilled immigrantsImmigrants with a foreign college degree or higher, typically possessing special skills or knowledge for a certain profession.3, naturalized citizens (immigrants who have become citizens) or temporary visa holders (not including work visas) are those most likely to experience brain wasteWhen highly-skilled immigrants can not utilize their skills in the workplace, despite their qualifications. Brain waste results in underemployment and unemployment.1.48, 49 Documented immigrants who do not hold work visas must enter the workforce and go through the typical job application process rather than being placed in jobs like those who hold work visas. Thus, immigrants who do not hold work visas must face barriers to career advancement in the US. Of skilled immigrants who do not hold a work visa, 25% are either underemployed or unemployed.50

The Process of Transferring Credentials

Evaluating and recognizing credentials leads to skill underutilization among skilled immigrants. Skill underutilization occurs because the requirements for transferring credentials vary depending on the state, occupation, and credential evaluation organization, which makes it confusing for immigrants to know what steps to take. The US does not have a federal system for evaluating and recognizing credentials abroad; these processes vary by state.51 States have their own rules and regulations for transferring and obtaining licenses and certifications, leading to inefficient transfer of degrees and credentials. If immigrants move to a different state, the requirements for transferring credentials change, and they often must start the recognition process over. Immigrants must go through credential evaluation organizations to get their credentials transferred and recognized in the United States.52 Credential evaluation organizations are accredited by the National Association of Credential Evaluation Services (NACES).53 Credential evaluations must be submitted to licensing boards, employers, and other training programs for skilled immigrants to get their credentials transferred to the US.54 However, most employers and states only accept credential evaluations from specified credential evaluation organizations, often making the transfer process more time-consuming for skilled immigrants.55

Many licenses and certifications are not transferable to other states for native-born and foreign-born workers.56 Oftentimes, federal training programs, such as the Medical Residency Match Program, are not recognized by certain states, making it increasingly difficult for skilled immigrants to meet training requirements or transfer credentials when they receive a new job or move to a different state.57

The requirements for transferring or obtaining licenses and certifications vary by occupation. For example, immigrant engineers must pass the Principles and Practice of Engineering (PEP) exam.58 Nurses, on the other hand, lack a specific course in pediatric nursing that is only offered in the US, yet in many colleges or universities, only full-time students can take that course.59 An organization in California found that immigrants, while often overqualified in their skill set, could not transfer their credentials to the state requirement.60 This barrier can lead immigrants to return to school to complete the courses and training required to obtain the credentials needed for their careers when they may not have needed to.

Photo by Romain Dancre on Unsplash

There is currently no research on how many US immigrants face barriers to career advancement. However, Canada has collected much research regarding barriers to career advancement for skilled immigrants, and it has been found that skilled immigrants in Canada face similar barriers to career advancement.61 A longitudinal study followed skilled immigrants in Canada from October 2000 to September 2001. Within 6 months of arriving in Canada, 47% of skilled immigrants had received foreign credential recognition.62 After 4 years of living in Canada, an additional 28% of skilled immigrants had received foreign credential recognition.63

Transferring college degrees is a lengthy process for immigrants in the US. Transferring degrees (like licenses and certificates) is often expensive and complex, and it is one of the most time-consuming parts of an immigrant’s career process.64 Transferring a foreign degree can take as little as several weeks or as long as several months to complete.64 Immigrants have a very difficult process when transferring their credentials to the US due to a lack of access to transcripts and documents from their home countries.65 Finding credentials for these immigrants can be almost impossible, with no federal US standards or regulations to help them.66 Others have documents that are not recognized in the US because different systems are used in other countries.67 Immigrants often must re-take licensing exams and trainings.68

There are many instances in which more schooling or training is required for career advancement in the US. There can be gaps in training and certification that need to be filled so that skilled immigrants are prepared to work in the US.69 The time and cost of transferring credentials and re-credentialing make it difficult for immigrants to complete the process, which often results in underemploymentDescribes highly-skilled immigrants who are working in low-skilled jobs.6 or unemploymentDescribes immigrants seeking employment but being unable to find work.7>.70

Immigrants who receive degrees in the US are 3 times more likely than US natives with degrees to work in high-skilled jobsFor the purpose of this brief: jobs that require a bachelor’s degree or higher.2.71 However, 25% of immigrants with foreign degrees are underemployed or unemployed, compared to 17% of those born in the US with degrees.72 Adult immigrants with a bachelor’s degree are 2–3 times more likely to be victims of brain wasteWhen highly-skilled immigrants can not utilize their skills in the workplace, despite their qualifications. Brain waste results in underemployment and unemployment.1 than those born in the US with a higher degree.73 The state of California has 450,000 immigrants with bachelor’s degrees who are underemployed.74 The US has 263,000 immigrants with medical and health degrees that are not working in their field.75 These numbers are only growing as increasing numbers of immigrants with college degrees are arriving in the US each year.76

Differences in foreign and US college systems and grading affect the credibility of transferred degrees.77 Many Western educators believe that international students are insufficiently adjusted to higher education in the US.78 Some immigrants may have only 1 course that does not transfer but can only take the needed course if they are enrolled as full-time students.79 This barrier forces immigrants to re-enter the education program, requiring more money and time and forcing them to work low-paid or “survival jobsJobs that require workers to have no more than a high school education and no more than 1 year of work experience.4” in the meantime.80 Furthermore, many immigrants who have been in their skilled profession for years have difficulty passing tests because they have not been enrolled in school in multiple years.81

License and Certification Process

After transferring of degrees, skilled immigrants often go through the re-credentialing process. The time and cost of certification make it difficult for immigrants to continue their careers in the US because certification is expensive and time-consuming. In addition, many immigrants struggle to know the requirements for certification due to differing standards by state and occupation. Therefore, skilled immigrants must go through a credential evaluation organization to identify the gaps they need to fill to continue their careers in the US. Credential evaluation organizations are either led by a national board or a state board, depending on the area of profession that the board covers.82 For example, foreign-educated medical doctors must go through a national board, the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG).83 Skilled immigrants must pass clinical skills and language proficiency tests and complete a residency program. This process can take up to several years to complete.84 All foreign-trained doctors go through the ECFMG for credential recognition and re-credentialing.85 On the other hand, state credential evaluation organizations often contradict other states, and it can be difficult for skilled immigrants to know what requirements they need to fulfill for career advancement.86 For example, the Alabama Board of Examiners of Psychologists (ABEP) requires foreign-trained clinical psychologists to pass a state psychology test for a license, pass the Professional Standards Examination (PSE), and have their education credentials examined to determine if more education is necessary.87 In contrast, the Idaho Board of Psychological Examiners requires immigrants to pass a written exam and complete 2 years of supervised experience before receiving a license.88

When immigrants lack credentials for their profession, it is very hard for them to receive the required training to complete re-credentialing in the US. It is a lengthy, complex, and expensive process, including evaluations of coursework, missing coursework, stand-alone courses needed, and other factors.89 The process is different for each profession, each having its own barriers. For example, foreign physicians must complete a 3–8 year residency in the US, regardless of how long they practiced their profession in their native country.90 Engineers must apply to lower-level positions to gain more experience in the US before continuing at the level of engineering they worked at before immigrating.91 Healthcare professionals must take exams that cost from $500.00–1,000.00 each time the test is taken.92 Some immigrants never advance in their careers simply because the financial stress of re-earning their credentials through additional training or programs is too burdensome.93 Once immigrants are in low-skilled jobs, they have fewer opportunities for economic advancement.94 Often, work experience in the US is required to get a license, but immigrants struggle to get the work experience they need without the license. This cycle prevents immigrants from obtaining licenses needed to work specific high-skilled jobsFor the purpose of this brief: jobs that require a bachelor’s degree or higher.2 in the US, which leads to immigrants staying in low-skill professions.95 Skilled immigrants are approximately 30–35% less likely than skilled native-born citizens to have an occupational license.96

Various institutions also play an important role in the process of obtaining licenses and certifications. Educational institutions, nonprofit organizations, unions, and other associations often operate state-level credential evaluation organizations.97 These institutions bring unique rules and qualifications to each credential evaluation organization. Thus, credential evaluation organizations do not hold skilled immigrants to the same standards for credential recognition and evaluation.98 Skilled immigrants struggle to know and meet the requirements for transferring and obtaining licenses and certifications in the US due to the messy network of differing state regulations and requirements that they must complete.99 Although 25% of skilled immigrants are either underemployed or unemployed, it is not yet known how many of these immigrants must go through re-credentialing.100

Lack of Employer Recognition

A lack of employer recognition contributes to skill underutilization because employers are unwilling to help immigrants to know or complete the requirements to continue their careers in the US, and some employers choose not to recognize any credentials from immigrants. Often, employers do not know the rules or regulations for their state licensing process and may find it appropriate to refuse foreign credentials. A survey of over 4,000 skilled immigrants found that 40% of immigrants said their employers did not recognize foreign work experience, and 35% of skilled immigrants said that their employers did not recognize foreign credentials.101 For employers to accurately accept or reject credentials, they must have access to international systems and have the ability to compare foreign credentials with American credentials.102 There is currently no relationship between US employers and foreign credential systems, and the US has never attempted to create one in the past.103 Because of this lack of relationship, employers often do not know how to recognize credentials and instead employ a third party for credential evaluations. Even when employers do have the ability to recognize foreign credentials, they will often hire native-born workers because the standards for recognizing foreign credentials are confusing. A study found that 83% of employed skilled immigrants had employer-recognized credentials, showing that recognized credentials are an important part of the hiring process.104

Photo by Sora Shimazaki

Acceptance of foreign credentials and degrees is regulated by states or employers. Many employer and state approaches assume that foreign education is inferior to US education.106 Many times, employers will not interview immigrants who received an education in a foreign country. A meta-analysis of 97 studies found significant discrimination against nonwhite people across 9 countries in North America and Europe.107 Specifically, in Canada, a study found that recent immigrants and refugees were unaware of their rights at work.108 In a cross-national field experiment, employers were individually interviewed and completed surveys. The interview and survey data showed that employers are often willing to pay their employees more if they are native-born and white.109 It has been found that in the US, prospective employers often stereotyped immigrants who are unemployed and viewed them as lacking motivation.110 Another study found that individuals who are unemployed for 8 months or longer had a 45% lower callback rate from prospective employers.111 Skilled immigrants in the US are at a greater risk of facing lower callback rates because they experience higher levels of brain wasteWhen highly-skilled immigrants can not utilize their skills in the workplace, despite their qualifications. Brain waste results in underemployment and unemployment.1 and, thus, long periods of time unemployed.

Cultural Literacy

A lack of cultural literacy makes it difficult for skilled immigrants to continue their careers in the US because immigrants struggle to network, apply for jobs, build resumes and cover letters, and comply with US verbal and nonverbal norms. Skilled immigrants arriving from foreign countries go through a dramatic change in culture. The cross-cultural adjustment and culture shock is a hindrance in the life transition to the US.112 Three similar studies have found that among immigrants in the US, acculturation, the process of learning and adapting to a new culture, was correlated with success in immigrants’ careers and education.113, 114, 115

Networking is a major factor in job searching in the US, and immigrants who are not aware of the US cultural norms cannot become involved in networking and gain social capitalSocial capital is the networks of relationships and shared values among people in a society.5 skills.116 A study of highly-skilled immigrantsImmigrants with a foreign college degree or higher, typically possessing special skills or knowledge for a certain profession.3 found a strong correlation between immigrants’ career success and their social capital.117 Multiple other studies have shown a relationship between immigrants’ social capital and increased likelihood of employment and higher executive positions.118, 119, 120 Although there is also a correlation between social capitalSocial capital is the networks of relationships and shared values among people in a society.5 and career success for US natives, skilled immigrants face this barrier more because they are not as familiar with the US work culture and norms.121, 122, 123

While immigrants may have formal skills needed for their line of work, they often lack the soft skills—job searching, interviewing, understanding the US workplace, and so on.124 The US job market is complex, with many networks to navigate. One process that may seem simple to Americans but that is very complex to foreigners is the job-application process. Building a resume is a challenge for skilled immigrant workers, as they are not aware of the cultural elements that go into building a strong and credible resume.125 Interviews are a challenge to immigrants who are not aware of US norms. Social conduct like eye contact, smiling, handshakes, and the volume of one’s voice greatly impact the impression made in an interview. Failure to comply with these social customs may come across as incompetent or unable to perform.126 Thus, immigrants are often disadvantaged in the hiring process.127

Photo by Alex Green

A large-scale randomized control trial, which was conducted in 28 cities, found that immigrant workers who were unaware of social norms were less likely to obtain and retain jobs.128 Other studies have found that immigrants who had greater social networks and who were more familiar with social norms were more likely to retain their jobs.129, 130, 131 Many skilled immigrants have the technological skills that accompany the job application process. Immigrants are unaware of the sources that are available to find work, making it incredibly difficult to identify career opportunities.132

Language Barrier

The language barrier contributes to skill underutilization because low English speakers are less likely to obtain jobs, skilled immigrants struggle to learn advanced English for skilled jobs, some courses and certification classes are only offered in English, and many immigrants experience language discrimination in the workplace. Low English speaking competency is one of the most significant factors for immigrant unemploymentDescribes immigrants seeking employment but being unable to find work.7>.133 Workers who speak English fluently are twice as likely to work in a high-skilled job, regardless of if they are native or foreign-born.134 Highly-skilled immigrantsImmigrants with a foreign college degree or higher, typically possessing special skills or knowledge for a certain profession.3 in the US who report speaking English “not well” are five times more likely to end up in a low-skilled job than those who are fluent in English.135 A study found that 6% of immigrant graduates in the US considered themselves low proficiency in English, while 18% reported medium proficiency.136

While many immigrants may be proficient in English, the technical vocabulary required for highly-skilled jobs make it difficult for immigrants to pass exams or classes.137 English classes offered for immigrants are not offered at advanced enough levels, leaving immigrants struggling to achieve their credentials.138 Highly-skilled fields, like medicine, require knowledge of advanced and technical terms. High levels of English proficiency are a “distinct characteristic of underutilized immigrant healthcare professionals.”139 Lack of English proficiency greatly hinders oral and verbal communication, thus impacting the chances of being hired. One study found that the English barrier was the most common barrier to work experience.140 Skilled immigrants with limited English proficiency earn 25–40% less than their English-proficient coworkers, and they are three times more likely to experience brain wasteWhen highly-skilled immigrants can not utilize their skills in the workplace, despite their qualifications. Brain waste results in underemployment and unemployment.1.141, 142 Research shows that immigrants who receive a degree from courses not taught in English are a high predictor of not passing licensure exams.143, 144, 145 Several US states require that all legal documents must be written in English.146 Foreign-born workers making their transition into the United States often struggle to translate their documents into English.147

Non-English-speaking foreign doctors meet the US standards for doctors and thus cannot qualify to practice medicine in the US. Foreign doctors often find work in the medical field, but not as doctors.148 Approximately 65,000 out of 247,000 (26.32%) of foreign-trained doctors in the US are not practicing.149, 150, 151 There are some fields that do not offer certifications in certain languages, and this barrier can prevent immigrants who speak certain languages from continuing their careers in the US. Manicure licensing is often offered in Vietnamese, leading many skilled Vietnamese immigrants to work at nail salons because the certification is offered in their language.152

A study found that US employers were more likely to hire people who have an American accent and less likely to hire people with a foreign accent.153 In another study, 70% of 2,000 immigrants said that they experienced discrimination in the workplace due to their skin color or accent.154 Many employers may require employees to speak English to the level required by a particular job, but they must avoid broad “English-only” rules.155 English-only rules are illegal in the workplace, as they go against Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.156 This act made it illegal to discriminate against an employee because of their national origin (including language).157 It has been argued that English-only rules empower English-speaking workers in the workplace and limit the empowerment of non-English-speaking workers.158 According to the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), 10.1% of the complaints they received (out of 6,213 cases) for employment discrimination in 2021 involved national origin, which often correlates to language discrimination.159

Consequences

Federal and State Level Money Loss

Skill underutilization leads to federal and state money loss because if skilled immigrants were able to continue their careers in the US, more jobs would be created, and thus, more money would be contributed to the US economy. The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) is a nonprofit organization in Washington, DC that conducts research and analysis on immigration and integration policies in the US. The MPI was the first institution to produce a numerical estimation for the amount of money lost each year due to skill underutilization for college-educated immigrants.160 “Total earnings losses due to low-skilled employment” is the amount of federal money lost annually due to 2 million skilled immigrants working low-skilled jobs.161 In other words, this calculation is the amount of money that the US loses due to underutilized skilled immigrants working low-skilled jobs rather than making more money in high-skilled jobsFor the purpose of this brief: jobs that require a bachelor’s degree or higher.2. The MPI quantified the number of total earnings made by the 2 million underemployed immigrants in the US, as well as the amount of money that these immigrants would be making if they were working high-skilled jobs. It is estimated that underemployed college-educated immigrants resulted in a loss of approximately $39.4 billion in annual wages per year.162 The US loses this money because immigrants who experience skill underutilization work survival jobsJobs that require workers to have no more than a high school education and no more than 1 year of work experience.4 rather than working high-skilled jobsFor the purpose of this brief: jobs that require a bachelor’s degree or higher.2 that the US could create for them if they were able to work in their careers.

Researchers with the International Test of English Proficiency (ITEP) used their analysis of the state tax systems to estimate the effective tax rates (ETR) that the US loses each year due to immigrant skill underutilization. The ETR is an estimate of the federal and state taxes that skilled immigrants would have paid if they were working high-skilled jobsFor the purpose of this brief: jobs that require a bachelor’s degree or higher.2. The ITEP estimates that the US loses $10.2 billion in taxes each year ($7.2 billion in federal taxes and $3 billion in state taxes). Based on “college-educated adults working in jobs that require lower levels of formal qualifications,”163 the calculations only include underemployed skilled immigrants and do not account for unemployed skilled immigrants. 37% of women with foreign degrees and 18% of men with foreign degrees were unemployed from 2009–2013.164 As skill underutilization among US immigrants increases each year, the number of skilled immigrants working low-skilled jobs increases. Consequently, the amount of federal and state earnings losses due to low-skilled employment will also increase.165

These economic costs vary by state, depending on the level of underemploymentDescribes highly-skilled immigrants who are working in low-skilled jobs.6 and the number of skilled immigrants in each state. Below is a graph of the top 7 states with revenue loss due to underutilization of immigrant skills from 2009–2013. The leading state is California, with an estimated $9.4 billion lost in annual earnings and $694 million lost in taxes.166

Poor Mental Health

Underutilized skilled immigrants suffer from poor mental health as a result of difficult career advancement.167 While there is a lack of overall statistics on the mental health of immigrants in the US, many studies and surveys have been conducted on this matter, revealing the hardships of career advancement for skilled immigrants and the impact that has on mental health. Employment difficulties are one of the biggest leading factors in mental health for skilled immigrants in the US.168 Securing employment, economic hardship, and low-skill job demands were all found to be major stressors for underutilized skilled immigrants.169 Skilled immigrants who come to the US with preexisting mental health conditions are especially vulnerable to a decrease in mental health.170 UnderemploymentDescribes highly-skilled immigrants who are working in low-skilled jobs.6 and unemploymentDescribes immigrants seeking employment but being unable to find work.7> are consistent factors linked with mental health across various studies.171, 172, 173, 174, 175 Job satisfaction is a major contributor to mental health.176, 177, 178, 179 Skilled immigrants often experience employment difficulties, economic hardship, and job satisfaction, which can result in a decrease in mental health.

A study found that advancement opportunities was a key factor for skilled immigrants’ mental health, and skilled immigrants were often dissatisfied with their career opportunities.180 A meta-analysis combining over 500 studies and 250,000 underemployed skilled immigrants found that job satisfaction was correlated with burnout, self-esteem, anxiety, and depression.181 Compared with US natives, immigrants working low-skilled jobs were found to experience greater disparities in their mental health.182, 183, 184

One study conducted in-depth interviews with 22 skilled immigrants and found that lack of income and loss of employment-related skills were the biggest contributors to the immigrants’ mental health.185 Most of the participants were concerned about the loss of their employment skills while working survival jobsJobs that require workers to have no more than a high school education and no more than 1 year of work experience.4. Anxiety, depression, worry, tension, irritation, and frustration were results of skill underutilization.186 Lack of income caused fear and worry about providing for family and dependents.187, 188, 189

Another factor for mental health was the loss of social status and increased feelings of loneliness and alienation as a result of working low-skilled jobs.190 Loss of social status because of underemploymentDescribes highly-skilled immigrants who are working in low-skilled jobs.6 was correlated with unhappiness, frustration, and anxiety. A study found that immigrants with at least 16 years of education in low-skilled jobs had lower self-rated mental health compared to US natives.191 Employment frustration was the primary reason that the skilled immigrants in the study reported having lower mental health.192

Struggle to Support Families Financially

Immigrant skill underutilization results in skilled immigrants earning a lower income, which often means that skilled immigrants struggle to support their families financially. UnderemploymentDescribes highly-skilled immigrants who are working in low-skilled jobs.6 and unemploymentDescribes immigrants seeking employment but being unable to find work.7> of skilled immigrants in the US cause financial strain and worry for many families. The average annual salary of underutilized skilled immigrants in the US was $35,000.00, which was $45,000.00 less than the average annual salary of skilled immigrants who are able to continue their careers in the US ($80,000.00).193, 194 In comparison, the average salary of skilled native-born US citizens was $67,870.00.195 A study found that US immigrants were, on average, more skilled than the global population.196

While working toward a professional job can be better in the long run, it is not realistic for many immigrants due to the time-consuming and costly nature of this process.197 The time and cost of certification often prevent immigrants from continuing their careers in the US and thus working survival jobsJobs that require workers to have no more than a high school education and no more than 1 year of work experience.4. The survival jobs that the immigrants take are not enough to financially provide for many families and keep immigrants trapped in low-paid positions with little room for economic advancement.198 Low-skilled employment makes it far less likely that immigrants can support their families, and working survival jobs due to skill underutilization causes financial stress, fear, and worry for immigrants supporting families. For families who can afford basic living expenses, underemploymentDescribes highly-skilled immigrants who are working in low-skilled jobs.6 limits family spending power, making it hard for immigrant families to participate in recreational activities or extracurricular activities that cost money.199

Many skilled immigrants must complete an internship or conduct volunteer work to become recertified for their careers.200 Volunteer work and often internships do not pay, which makes re-certification out of reach for skilled immigrants who need to support their families because the time and cost of re-certification are too much to handle while supporting a family.201 Other immigrants have family members outside of the US, and working low-skilled jobs limits the amount of money that they can send to their families in foreign countries.202 The United Nations found that approximately 1 in 9 (11.11%) people globally were supported by migrant workers who send money to them.203, 204 Foreign workers send between $200.00–300.00 to their families per month.205 Not having the money to send to family due to skill underutilization causes distress for immigrant families. Often, skilled and highly educated immigrants will become employed in work without telling family because they are desperate for the money and are often embarrassed about their new working conditions.206 While skilled immigrants have the opportunity to eventually become recertified and re-educated for their careers, immediate financial and family matters make it extremely difficult to do.

Best Practices

Career Counseling for Skilled Immigrants

Skilled immigrants often know the resources that they have for training, licensing, transferring credentials, and other crucial factors in their professional career path in the US. Career counseling for skilled immigrants provides resources, knowledge, and information needed to continue their work in the US.207 Career counseling provides skilled immigrants with individualized assistance with career counseling, allowing them to gain specific and reliable resources to help with their career struggles.208 This resource is extremely valuable because immigrants in the US come from diverse backgrounds. This cultural and career diversity creates a need for small-scale assistance.209

Photo by EVG Kowalievska

In 1999, Jan Leu, a refugee resettlement caseworker, started Upwardly Global. Upwardly Global is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization whose mission is to eliminate employment barriers for skilled immigrants in the US. The organization is funded mainly through donations and grants.

Upwardly Global provides career counseling and services to skilled immigrants who are struggling to continue their careers in the US. They have offices in 4 cities in the US, and they reach skilled immigrants throughout the entire US through remote career counseling. Upwardly Global develops professional licensing guidelines that help immigrants understand all the options that they have, whether it be continuing their career or choosing a new career path.210 This understanding helps skilled immigrants to know all their options and confidently choose what would be best for their situation.

Career professionals at Upwardly Global have in-depth knowledge of professions and state-specific requirements for each profession. Explanations of licensing processes and alternate careers are discussed. Skilled immigrants can identify potential setbacks that they may encounter, with the time and cost estimated with each setback. Immigrants who receive career counseling from Upwardly Global are given enough resources to evaluate for themselves.211 Immigrants who receive career counseling from Upwardly Global are able to decide the path they want to take and estimate the consequences and successes of each path. Those who wish to continue their careers in the US are connected to additional resources for improving skills and potential employers. Upwardly Global has partnered with over 350 businesses and employment centers to help immigrants network and find employers.212 One example of a business partner with Upwardly Global is the Colorado Welcome Back Center, which helps foreign-trained physicians match with a residency. Several immigrants have been connected to this program and were matched with a residency program.213 Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (LARA) has also partnered with Upwardly Global. LARA has created a hotline for skilled immigrants in Michigan seeking assistance for career advancement in the US.214

Impact

Before coming to Upwardly Global, most of the alumni worked in survival jobsJobs that require workers to have no more than a high school education and no more than 1 year of work experience.4, 37% of them lived below the federal poverty line, and 61% of them were vulnerable to public charge, which means they were likely to become dependent on the government for financial assistance.215 Career counseling from Upwardly Global has made an impact by assisting over 7,500 skilled immigrants in finding a job in their respective careers.216 After 1 year in the Upwardly Global career counseling program, immigrants from Upwardly Global make an average salary of $49,899.00 per year.217 Alumni from Upwardly Global make an average of $55,000.00 per year, and they contribute $252 million in tax revenue and consumer spending money each year. More than half of the alumni from Upwardly Global work in STEM positions that are normally hard to fill and even harder to get as an immigrant.218 This impact measurement is evidence of the change that Upwardly Global has made with its programs.

Gaps

While Upwardly Global has measured the impact of its career counseling, no impact has been measured for general career counseling for skilled immigrants. Part of this reason is that career counseling is individualized and difficult to replicate due to the diverse needs of immigrants. Upwardly Global is one of the only large-scale organizations that provides career counseling to skilled immigrants in the US.219 There is a lack of large-scale organizations because varying state qualifications makes it difficult for organizations to serve immigrants from different states. Individualization for career counseling is difficult to make large scale, with needs that change with each immigrant.220 Upwardly Global’s custom guides and resources for various immigrant situations can be useful to other organizations and expound the amount of impact career counseling provides to skilled immigrants.

Accessible and Cheaper Training or Retraining for Skilled Immigrants

Accessible and cheap training is hard to find for skilled immigrants in the US and is one of the most significant barriers to immigrants continuing their career path.221 The requirements for training and transferring of credentials vary by state. Various organizations have connected with states to create training services for skilled immigrants. These organizations are specialized for the diversity that accompanies skilled immigrants.

In 1970, Anne O’Callaghan founded the Welcoming Center for New Pennsylvanians. Funded primarily by donors and partners, The Welcoming Center is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) whose mission is to reduce brain wasteWhen highly-skilled immigrants can not utilize their skills in the workplace, despite their qualifications. Brain waste results in underemployment and unemployment.1 in Pennsylvania, and its focus is on high-growth industries, including auditing, accounting, engineering, and teaching.222 The Welcoming Center develops resources addressing the needs of skilled immigrants in Pennsylvania. They provide 12 weeks of full-time paid work experience for immigrants with foreign degrees. During these 12 weeks, the Welcoming Center provides coaching and support, educating the immigrants and providing resources and information on their careers.223 This new program, launched in 2017, supports a cohort of about 15 skilled immigrants for 12 weeks. This small number of immigrants helps the coaches spend adequate time with each immigrant and personalize their experience to their needs.224

In 1987, Bnai Zion initiated the Cooper Union Retraining Program for Immigrant Engineers. This program is run through Cooper Union college in New York City. Their mission is to support immigrant, refugee, and asylee engineers as they work toward advancing their careers in the US. This program provides coursework for engineers to update the skills and experience needed for engineering in New York.225 The goal of the program is to help engineers increase their technical knowledge and to gain a stronger understanding of the soft and hard skills employers require. The organization offers free training in the evenings, making it accessible and cheap for skilled immigrants to receive training and support.226 The evening training sessions have different courses, focusing on potential skill gaps that engineers may need to know for working in the US.227 This training helps members of the program to prepare for certification exams.

Impact

Though impact has not been measured on a large-scale, various organizations have measured their impact on assisting skilled immigrants to continue their careers through accessible and cheap training.228 The Welcoming Center for New Pennsylvanians has hosted several cohorts since its launch in 2017.229 Every member of their various cohorts has used their 12-week training experience to find employment in various fields.230 Additionally, 40% of their alumni have found positions within the city they live, which brings diversity to cities that have hard-to-fill positions.231, 232

The Cooper Union Retraining Program for Immigrant Engineers in NYC serves over 225 students a year. They have found that 65% of the people that they serve found a position where they can support themselves in their engineering careers.233 The Chicago Bilingual Nurse Consortium has helped over 800 nurses from over 60 countries to become a nurse in Illinois.234

Gaps

The large-scale impact is hard to measure for accessible and cheaper training for skilled immigrants because most current organizations are smaller and focused on specific populations or professions.235 It is difficult to serve large populations in situations that require specific guidance and training. Varying state requirements for skilled immigrants make it harder to use the same program in different states. Replication is, therefore, difficult, and no measurements have been done to determine how accessible and cheaper training for skilled immigrants affects the consequences mentioned in this brief.

Preferred Citation: Arnita, Cassie. “Barriers to Career Advancement Among Skilled Immigrants in the United States.” Ballard Brief. December 2022. www.ballardbrief.byu.edu.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints