Intergenerational Poverty in the United States

By Monica Privette-Black

Published Spring 2021

Special thanks to Lorin Utsch for editing and research contributions

Summary+

Though the United States is one of the highest-income countries in the world, there are still hundreds of thousands of citizens living below the poverty line. More children live below the poverty line than any other age group. The racial demographic and distribution of modern-day poverty can be traced back, in part, to policies such as gentrification and redlining. School system failures and a lack of access to social capital also contribute to the prevalence of intergenerational poverty. The consequences of intergenerational poverty include food insecurity, birth and developmental issues, unsafe living conditions, and increased risk of violence, incarceration, and victimization. Every consequence of growing up in poverty acts as another barrier for someone to rise above the poverty line. Programs that focus on developing connections, social skills, and a mentor relationship with a trusted adult can enable youth to overcome such barriers.

Key Takeaways+

Key Terms+

Poverty line—“set minimum amount of income that a family needs for food, clothing, transportation, shelter, and other necessities.”1

High-poverty—refers to an area in which 20% or more of the population lives in poverty.2

Persistently poor child—a child who lives in poverty for half (at least 9 years) or more of their childhood (until the age of 18).3

Poverty rate—the percent of the population living below the poverty line.

Redlining—“a process by which banks and other institutions refuse[d] to offer mortgages or offer worse rates to customers in certain neighborhoods based on their racial and ethnic composition.”4

Gentrification—“a process in which a poor area (as of a city) experiences an influx of middle-class or wealthy people who renovate and rebuild homes and businesses and which often results in an increase in property values and the displacement of earlier, usually poorer residents.”5

Human capital—“the economic value of a worker's [or person’s] experience and skills. This includes assets like education, training, intelligence, skills, health, and other things employers value such as loyalty and punctuality.”6

High-income country—a nation that has a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita above a set global threshold. In recent years, this threshold is ~12,300 USD.7

OECD—the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. “An international organisation [whose] goal is to shape policies that foster prosperity, equality, [and] opportunity” that is composed of 37 high-income countries.8

Context

Q: What is intergenerational poverty?

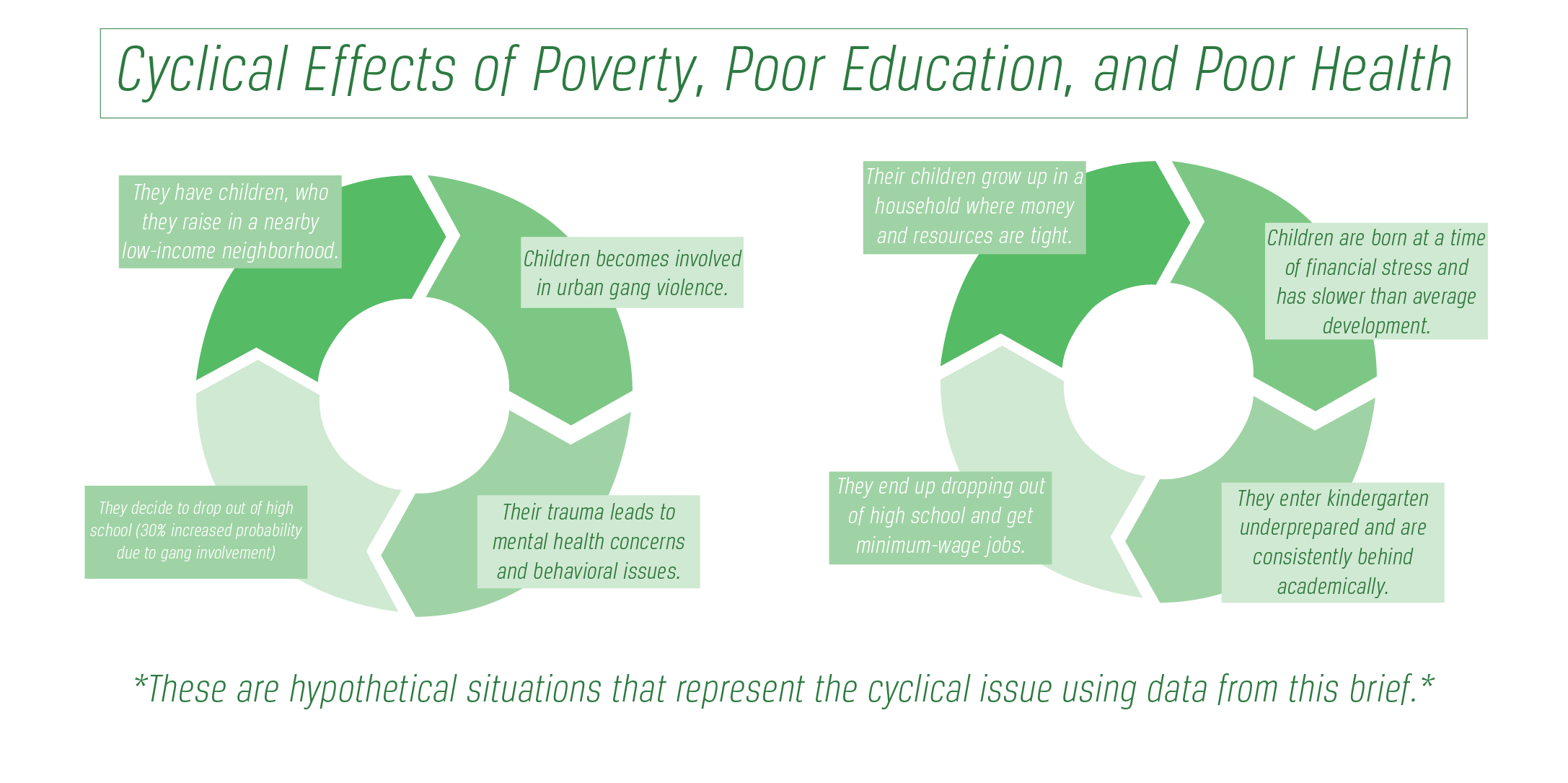

A: Poverty is the chronic occurrence of not having enough money to pay for one’s expenses, including rent, adequate healthcare, food, or even hygiene products.9 It is often measured by what needs exist (e.g., estimated food cost for a family of 410) and how much of that resource is available for a household.11 Intergenerational poverty is the cyclical occurrence in which a child goes from being born in poverty to raising his or her own children in poverty. The United Nations considers poverty to be a “violation of human dignity” and claims that chronic poverty is an infringement of human rights.12 Thus, the poverty cycle would be considered a violation of human rights, especially for the children who are born into such circumstances.

According to a 2009 study, 10.7% of the population that was born into poverty between the years of 1970 and 1990 in the United States will live over half of their lives in poverty,13 which comes out to approximately 38–40.5 years in poverty. Additionally, studies show that 90.9% of women give birth to their first five children before the age of 34,14 so most women in this generation born in poverty who have children are more than 90% likely to have children in poverty. Given the trends of intergenerational poverty, an estimated 6.4% of children born in poverty spend all of their lives in poverty,15 which consequently perpetuates the poverty cycle further. Chronic, intergenerational poverty is not a result of a one-time financial crisis but of larger factors passed from generation to generation.

Q: How does the United States compare globally in regard to poverty?

A: In a 2019 study, the United States was reported to have a poverty rate of 17.8%, the 3rd highest rate of the other 36 OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) nations.16 Additionally, the United States’ poverty rate was 6% higher than Canada’s, a nation with economically similar make-up.17

Many professionals in the field have considered the United States to be an outlier among other high-income countries (such as Canada, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Sweden, and Norway) due to the fact that in 1979, the US child poverty rate was above 50% and has remained higher than other similar countries since.18 A 2018 study found that 38% of the world’s most poor population among high-income countries lived in the United States.19 Nearly all other high-income countries do not struggle with poverty to the same extent as the United States.20 Additionally, compared to a similar set of countries, the United States has the smallest public expenditure (welfare and in-kind donations) when accounting for overall GDP.21

Q: What are the current poverty trends in the US?

A: Poverty rates in the United States shift frequently. In 1993, the United States saw a peak rate of 18% of children living in poverty and then rates fell.22 However, since the first decade of the 21st century, the rate of child poverty has had a continual increase23 while the overall poverty rate in the United States has decreased annually since 2010.24 This trend has continued, with the overall national poverty rate decreasing while the national child poverty rate rises. In fact, in recent years a larger percentage of children live in poverty than the overall population.25

Child poverty is a problem in all types of communities. Historically, urban areas have had the highest poverty density.26 Over time the influence of gentrification has shifted the concentration of poverty from the cities to rural areas.27 These attempts to add infrastructure and new, higher-quality buildings to a city often results in torn-down affordable housing and, in turn, a demographic shift in urban areas. This shift adversely affects minority communities by shrinking options for the disadvantaged people who live there while increasing options for the more financially stable.28

From the early 1990s to 2013, the rural and suburban child poverty rates increased,29 a likely result of years of gentrification. By 2018, nearly 80% of counties with the greatest poverty were rural.30 These counties have also had high poverty rates for at least the past 30 years.31 Thus, intergenerational poverty is a trend that occurs in both large cities and in rural areas.

Q: What is child poverty?

A: Child poverty is when a child is born into a household that has an income that is less than half the median national income, given the family size.32 Since the decisions of a child do not determine socioeconomic status, the child poverty rate is the most precise indicator for the percent of the population impacted by intergenerational poverty.

In 2020, of the 74 million children living in the United States,33 an estimated 1 in 6 children lived in poverty.34 There were more children in poverty than individuals of any other age group.35 This data suggest that perhaps intergenerational poverty is the leading factor of poverty across the nation.

Thirty-two percent of persistently poor children spend half of early adult life in poverty, while only 1% of never-poor children do.36 In addition, only 16% of persistently poor children are able to escape poverty between the ages of 25 and 30.37 Due to one or a number of factors, these individuals are unable to climb above the poverty line and must subsequently raise their own children in poverty.

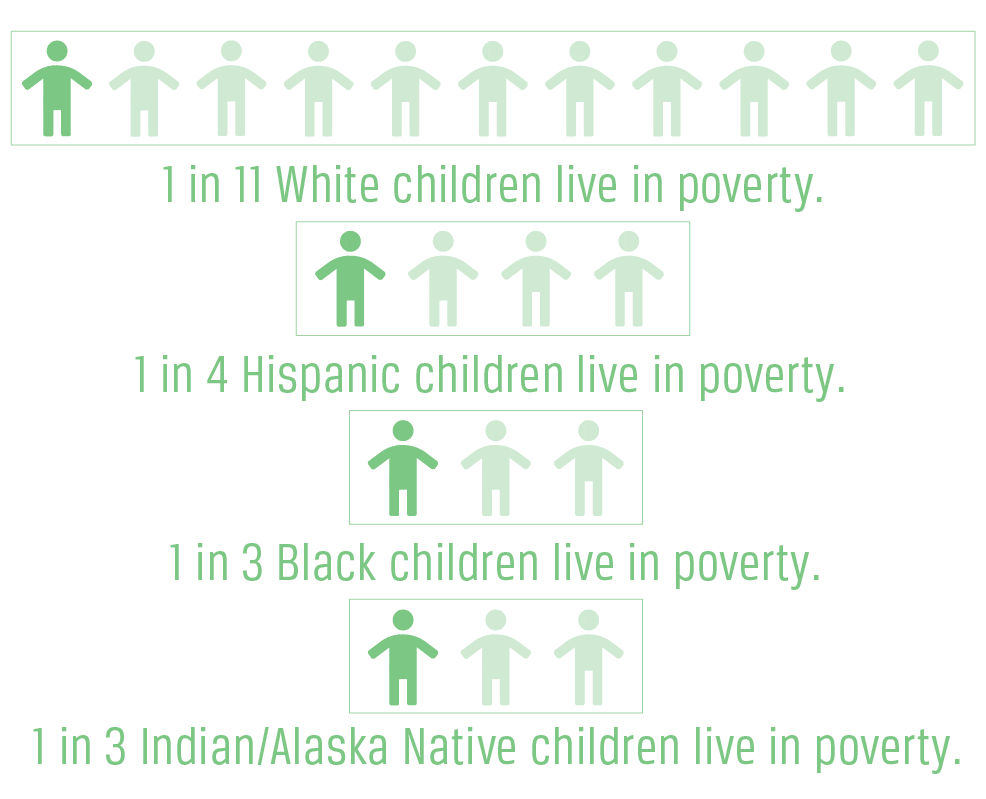

Q: How are child poverty rates different by race?

A: Of the 1 in 6 children that lived in poverty in 2020, 73% of those were children of color.38 One in 11 White children are impoverished compared to 1 in 3 Black or American Indian/Alaska Native children and 1 in 4 Hispanic children.39 One study found that a Black child is around 4 times more likely to live his or her entire life in poverty than a child of any other race.40 Moreover, 77% of all Black children live in poverty before adolescence, and of those, 69% live in poverty for 9 or more years.41 In short, children of color are statistically more likely than White children to live in poverty, with Black children being the most susceptible.

Q: What will this brief focus on?

A: There are many individual factors that contribute to poverty, such as an unsustainable minimum wage, and many methods of leaving poverty, such as job bonuses, trades, certificates, and higher education. However, cyclical and systemic variables often inhibit someone in poverty from accomplishing any of the prerequisites required to obtain these advantages, such as completing their high school education. As such, this brief focuses on and more fully examines these cyclical and systemic factors. Additionally, poverty and intergenerational child poverty are not the result of an individual’s actions or failure to act. Instead, existing systemic barriers hinder people from socioeconomic mobility.42

Contributing Factors

Redlining

The United States created a new wave of poverty when in 1930 the Federal Home Administration divided cities into categories, labeled minority-dominant regions unfit or unsafe for mortgages,43 and refused to allow minorities to live in any other type of city. As a result, low-income White people and many minorities were forced to grow up in areas with low equity, less infrastructure, and virtually no home ownership.44 Since economists consider home ownership to be the most consequential method for building both personal and intergenerational wealth,45 redlining is still playing a role in modern-day intergenerational poverty in the United States.46 Those who were refused mortgages from 1930 to 1968 were not able to pass that estate on to the next generation, which increases the wealth gap and perpetuates poverty.

Even though the practice of redlining and discriminatory gentrification was officially banned in 1968, its results from previous generations continue to negatively impact minorities today.47 Just over 66% of the metropolitan areas that were ranked as high-poverty in 1980 held the same ranking 30 years later, such as Montgomery, Alabama; Flint, Michigan; and Denver, Colorado.48 In 2020, 1 in 4 Black Americans and 1 in 6 Hispanic/Latinx Americans still lived in high-poverty neighborhoods,49 neighborhoods they were forced into 90 years prior. Additionally, zip codes have been shown to directly correlate to a person’s future income. Recent trends in tax records suggest that a child’s expected annual income can be determined by where he or she lived until the age of 23.50 More specifically, an adult’s income is expected to approximate the median of the county he or she lived in growing up.51 The longer a child lives in a county, the higher the likelihood that the county will impact their future income.52 It is evident that minority children who grow up in previously redlined areas are at a significant disadvantage, since the majority of these areas are still classified as low-income areas. This disadvantage is also due to a lack of inherited wealth, lack of access to close resources, and a variety of barriers keeping the family from relocating.53 Any combination of these obstacles often results in an inability for families to escape poverty and leads them to raise their own children in similarly impoverished circumstances.

School System Failures

Receiving a quality education provides skills and experiences that are necessary to have greater future financial opportunities, which in turn enable people to escape poverty. One of the factors that acts as a barrier to children getting the needed education to escape poverty is a lack of early-childhood intervention on the part of the school system. Many children who grow up in poverty experience delayed brain development due to poor nutrition and less mental stimulation, among other factors.54 This delayed development can contribute to less than half of impoverished kids being ready for kindergarten.55 Studies show that additional resources or attention to the students who are in need can often ameliorate the problem.56 A study found that even a $1,000 raise in a household’s annual income could result in a 6% increase in math and reading scores.57 However, most low-income households cannot afford to pay for extra educational support for their children. Since this early-childhood education intervention is largely unattainable for those in poverty, a gap in literacy levels and test scores begins to be observable in kindergarten for many students.58 In cases where this problem is not addressed, the child may continue to fall behind his or her peers and fail to complete his or her education. For instance, research demonstrates that if a child is not a proficient reader by the time he or she is in third grade, the child is 4 times more likely to drop out of high school.59 Without having a mentor or the special attention given to a student in need before he or she is 8 or 9 years old, the student is not likely to stay in school, with many students feeling as though the school system failed them.60 In fact, 1 in 10 students from low-income families drop out of high school, but only 1 in 100 students from higher-income families do the same.61 This trend is significant because graduating from high school or obtaining a GED is one of three factors that has a 98% success rate for helping an individual to attain middle-class status or at least move out of poverty.62

This problem is not unique to secondary education, as there have also been similar trends throughout postsecondary education. Only 11 percent of low-income, first-generation college students who enroll in a 4-year institution earn their degrees within 6 years, while 55 percent of their higher-income peers do.63 This trend reveals that even after overcoming initial barriers to attending college, a student who comes from poverty is 5 times more likely to drop out of college due to financial, social, or other personal reasons.64

A postsecondary degree is a powerful way to get out of poverty because it increases one’s earning potential. As a reference, those who only have a high school diploma make 62% of what someone with a bachelor’s degree earns.65 People who do not have the opportunity or means to go to college, or those who end up dropping out of college, may face extreme difficulty when trying to make a comfortable living, as they must compete against others who hold college degrees. Therefore, the problem of cyclical poverty starts the first day of kindergarten and has the potential to affect a child’s entire life, since a child who is struggling academically is statistically more likely to drop out of high school and even less likely to attain a college degree.

Lack of Social Capital

One powerful tool to help an individual rise out of extreme poverty is social capital; therefore the lack of social capital is one of the contributing factors of poverty. This brief and other academic articles emphasize social capital as an asset—not just having more connections but having connections that benefit a person.66 These connections often enhance the financial, social, and even emotional aspects of an individual’s life. Having a large number of deep and lasting connections actually increases fulfilment and overall happiness.67 Social capital allows an individual to utilize other’s skills and resources, such as asking a relative or neighbor to help with one's taxes free of charge.68

A study conducted in low-income New York suburbs found that the characteristics of an area, instead of individual factors, act as a barrier to different types of social capital.69 This study reviewed three types of social capital: bonding (strong relationship ties with family or friends), bridging (exchange of material or emotional resource from outside one’s immediate group), and linking capital (valuable connections to organizations and formal networks, such as nonprofit, outside of one’s neighborhood).70 The study found that although some residents in lower-income areas have connections, these connections are not dense; furthermore, overall linking capital to an organization that can provide prolonged assistance is the weakest of all types.71

In order to combat the limited beneficial social capital that is available to those living in poverty, many lower-income students and even adults need extra support to manage the complexities of their situations.72 However, there is a negative correlation between level of poverty and social capital; those with the highest poverty rates have less social capital and those with no poverty often have much more social capital.73 Therefore, in areas of high poverty, social capital is often low and people from those communities are at a larger social disadvantage.74 Even though a small amount of social capital is a result of intergenerational inheritance, living in poverty or in a poor neighborhood contributes to overall low social capital.

A key aspect of social capital is having a mentor or a professional network. A study that created a networking group for low-income students and alumni mentors while they were attending a boarding school found that the students were able to achieve social mobility, increase their number of meaningful connections, and later rely on those experiences and learned skills as preparation for a college education.75 A relationship with a mentor from a different socioeconomic background often helps students find motivation for long-term career goals, trust, and helpful advice that they might not be comfortable asking for elsewhere.76 In other instances, a mentor may be a coach or teacher who devotes specific time or attention to the individual. Sports coaches have proven to reduce delinquency and crime among low-income youth since they act as a positive role model and often a “social father” figure.77 In situations where family members might not have the ability to act as a mentor or guide, any trustworthy adult mentor can provide an invaluable connection.

A prime example of a benefit of social capital is learning about or being referred to a job by a mentor, friend, or family member. In fact, a LinkedIn study discovered that 70% of people end up getting a job at a company where they already have a connection.78 Even more so, around 66% of referrals are hired.79 Companies have also found that referrals have lower turn-over rates and are likely to stay with the company longer.80 Therefore, having more connections eliminates some barriers to escaping poverty, such as struggles with attaining employment or general job instability. Being able to get out of poverty on an individual level increases the likelihood of raising a family out of poverty as well, since children are more likely to be born in higher-income households. Therefore, because impoverished individuals have less access to social capital, they face additional barriers to accessing resources that could help them to escape poverty and thus end the cycle of intergenerational poverty.

Consequences

Due to the cyclical nature of intergenerational poverty, many of the consequences discussed in this brief are also contributors to keeping a family in poverty.

Health

Food Insecurity

Major consequences of intergenerational child poverty include health and development concerns. Since many impoverished families do not have the financial means to provide for the basic needs of the family, many children are affected by not getting the nutrients they need for development.81 A study of other OECD and high-income nations demonstrated that low-income children in Spain and France (nations with a lower child poverty rate per capita than the United States, indicating that similar or more exacerbated results would likely be found in the US) are three times less likely to eat fruit, vegetable, or protein every day as compared to non-poor children.82 There is also a prevalence of iron-deficiency anemia, in children from lower-income homes in the US.83

Child food insecurity has also been linked to an increased likelihood of eating disorders and/or obesity in adulthood.84 Low-income children are 21% more likely to be obese compared to their peers.85 This likelihood is often the result of unhealthy eating habits and relationships with food, especially unhealthy food. A longitudinal study also found that a recurrently poor child is 1.5 times more likely to become obese than a never-poor child86 and 17% of that population has an eating disorder of some kind as adults.87 Additionally a Canadian study found that homes with any level of food insecurity in turn pay 16% to 76% more for healthcare and medicine than other households.88

An upbringing in a home without adequate food, as is the experience of most children in chronic poverty, leads to negative physical, emotional, and behavioral effects.89 Many of these children do not have habits of eating a balanced diet, do not get the appropriate nutrition intake, and may even develop an eating order later in life.

Birth and Developmental Issues

In New York City, the largest city in the United States, counties in previously redlined areas still demonstrate high rates of high risk and preterm births.90 A California study also found a correlation between those living in previously redlined areas and preterm birth and low birth weight.91 High risk birth or preterm births increase the risk of infant and mother mortality and are likely to cause persistent health issues for the infant and mother. These data are crucial to understanding the long-term nature of intergenerational poverty, since children in these areas even today are still experiencing and living with the long-term effects.

Additionally, mothers who experience financial stress (as is the case for most impoverished parents) experience an increase in cortisol secretion, which can have negative health effects on her child during and following pregnancy.92 More specifically, due to brain development impediments in the womb, children born to mother experiencing chronic stress often have an IQ score of five points lower than average and are almost twice as likely to have chronic health conditions as their higher income peers or even their siblings born during a more financially-stable period for the family.93 This familial and parental stress is also evident in the children who are twice as likely to struggle with stress as a mental health concern than their peers.94

Another disadvantage of growing up in poverty is the deterioration of a child’s working memory during the first 13 years of life.95 This memory loss is a side effect of the heightened physiological stress that often accompanies poverty.96 The stress and physical burden that poverty has on mothers and children starts in the womb and has lifelong effects on the health of the child.

Living Conditions

An additional consequence of intergenerational poverty on children is the increased likelihood of living in a dangerous space. A 2016 report showed that a household below the poverty line is more likely to lack a functioning smoke detector or a safe roof or stairs.97 The children living in these households are more likely to be involved in accidents such as falls, burn, or other unsafe events.98

Many impoverished families are forced to live in affordable housing areas because the rent prices have been decreased to an amount that they can afford to pay. Characteristics of affordable housing areas include less-desirable locations, air pollution, and structural health concerns. Asbestos, black mold, and lead have been found in many lower-income areas, especially in older housing units.99 People living below the poverty line also face a 20% increase in exposure to vanadium and 18% to elemental carbon.100 These elements were found to be associated with cardiovascular and lung disease.101

Problems such as lead runoff also largely disadvantage communities in poverty. One prime example was the Flint Water Crisis that occurred in 2015, when the water in Flint, Michigan, a city whose population is 40% below the poverty line,102 was discovered to be unsafe and have high levels of toxins.103 Doctors found that the blood lead levels had doubled in many children104 and appropriate precautions were taken. While lead poisoning is dangerous for all populations, children are the most affected as it can lead to brain developmental issues, anemia, and hypertension, among other problems.105 Recent findings have shown that some of the younger children (around 3 years old) at the time of the poisoning now struggle with hand-eye coordination, are not developing as quickly, and have lapses in their long-term memory.106 However, in other cases the long-term effects may not be manifest until these children reach adulthood that the long-term effects become manifested, so continued longitudinal data is not yet available.107

Not having the means to afford housing has caused some people to experience homelessness. Although homelessness happens mostly in single parent households108 as well as instances of domestic abuse,109 children and families can end up homeless given other circumstances. In 2017, 21% of all homeless people in the United States were children110 and 90% of homeless children end up staying at a shelter.111 However, 90% of the typical families who fall homeless experience severe trauma,112 increasing stress that impedes children’s long-term mental stability. Living in an area of high poverty and being homeless can have detrimental effects on the safety of a child.

Violence, Incarceration, and Victimization

Adolescents growing up in low-income urban areas are at an increased risk of joining a gang or becoming involved in gang violence113 due to exposure in the community and the social capital (often negative) gang affiliation offers to provide. One study even found that 89% of low-income children interviewed had been involved in a gang sometime in their life.114 Some see this affiliation as a way to rise to a higher socioeconomic status,115 and others feel as if they have no better option to stay safe in their community. Those involved in gangs or those just exposed secondhand to community gang violence from a young age experience similar mental consequences as children soldiers in other countries.116 These mentally and emotionally damaging impacts can lead to behavioral issues at school and increased violence within the home.

Other adverse effects of gang involvement include drug and alcohol use and dropping out of school.117 Once an adolescent is in a gang, they are 30% more likely to drop out of high school.118 Children in poverty are already at risk of dropping out of high school and gang activity only amplifies this potential risk.119 As a result of gang participation and dropping out of a high school, these youth are put at a higher risk of ending up in prison120 or getting involved in the juvenile correction system.121 Many gang members end up serving jail time, although ambiguous prison records fail to provide specific data. Mass incarceration, a direct consequence of gang violence, adversely affects low-income communities of color and is a major hindrance for low-income mobility.122 (For more information on this issue, read the Ballard Brief on Mass Incarceration in the United States).

High rates of incarceration of low-income people, including gang members and even children, may be due to the fact that those living in a high-poverty, violent area are more likely to have more police surveillance and more likely to be convicted of a crime they did or did not do.123 Around 75% of police misconduct happens in neighborhoods under the poverty line, which puts all members of low-income communities at risk of incarceration, regardless of gang affiliation.124

Impoverished children and families are adversely affected by the issue of mass incarceration and false imprisonment. One in 25 low-income children has a parent in prison,125 and these children are more likely to undergo mental health struggles and have behavioral issues.126 Additionally, while one parent is in prison, family income is likely to be less and the household is at a higher risk for exacerbated poverty.127

Violence in communities, gangs, and crime affect children in many ways: These circumstances are detrimental to their mental health and can lead to a life of incarceration or continuous run-ins with the criminal justice system for children or parents. All of these also have potential long-term consequences, including not completing high school or having a felony record, which exacerbates the existing barriers to rising out of poverty.

General Economic Drag

Intergenerational poverty has severe effects not only on individuals and their families but also on the nation as a whole. For example, the estimated costs of child poverty in the US are just over $1 trillion annually128 with welfare costs accounting for around $500 billion. In recent years, the combined expense of all federal welfare programs came to make up the largest item in federal spending.129 Therefore, if there were resources equipped to address child poverty, the United States would save trillions of dollars over time.

The United States is also affected by a loss of human capital, since human capital and potential can be a cost of children growing up in poverty.130 As previously discussed, there are many factors that lead up to 10% of low-income students131 dropping out of high school. Many of the children who drop out are less able to contribute to the national economy because they hold lower-paying and low-skill jobs. This loss of human capital results in a deficit of up to $2 billion less in federal tax revenue annually,132 since individuals who dropped out of high school are likely to make significantly less than individuals who graduated high school.

Practices

The United States has many systems in place to provide temporary shelter, food donations, and monthly living stipends to those in poverty.133 However, these efforts have not proven effective in eradicating poverty or stopping its continuation for the next generation. Government policy and nonprofits must focus on funding programs that directly improve the social environments of families and children in order to tackle intergenerational poverty.134

Friends of the Children

Mentorship is a proven method to overcoming barriers as it helps children to establish a connection outside of their direct community, which increases social capital. Likewise, data from mentor-based programs show positive results for students who have a constant, reliable adult mentor.135 Many well-known programs such as Big Brother Big Sisters have found that this type of mentoring has profound impacts on a child’s life.136 Mentors also give emotional support to a child who otherwise may not have constant housing, such as those who may not have consistent adult influence or those in the foster care program, since 13 percent of children in the US foster care program previously lived below the poverty line.137 Effective mentorship programs in postsecondary institutions that support first-generation students with services such as extra academic support, study skills workshops, peer tutoring, and regular meetings with an advisor to track performance and address concerns have also proven effective to increase retention and graduation rates.138

Often the presence of a dependable adult figure helps teach youth or young adults emotional maturity, communication skills, and other skills to overcome barriers to escaping poverty.139 This increased social capital and experience with social skills provides tools for children that statistically lessens the effects of intergenerational poverty.

Friends of the Children is a nonprofit based out of Portland, Oregon, and operates in surrounding cities of Oregon and Washington. This organization pairs a “salaried professional mentor” to a child, from the end of kindergarten until his or her high school graduation.140 While this model is similar to that of Big Brothers Big Sisters, the time commitment of 12.5 years that each Friend (mentor) gives to each youth (referred to as Friend Youth) is unprecedented. The organization works with teachers and monitors students in low-income school districts during kindergarten. At the end of that school year, the organization chooses which kids seem to have the greatest need to join the program. Over the next 12.5 years, Friends follow a set curriculum that helps Youth develop key traits and focus on advocating for their healthcare, education, and whatever else is determined by the Friend and the child’s caregiver.141

Impact

The outcomes of the Friends of the Children mentor program are optimistic. The program has grown to 4 branches, currently has 45 Friends,142 and has served a total of 510 youth as of 2019.143 The program focuses on improving 3 long-term outcomes: increased high school graduation rates, decreased involvement with the criminal justice system, and decreased early parenting.144 While 60% of youth in the program have a parent who has been involved with the US criminal justice system, 93% of the kids in this program avoid the criminal justice system altogether.145 Likewise, 83% of the Friends Youth graduate high school,146 which is consistent with national average rates.147 Without a Friend mentor, however, a low-income child is more than twice as likely to drop out of high school.148 Since not having a GED and incarceration are barriers to escaping poverty, Friends of the Children is statistically enabling children to escape intergenerational poverty. Although the sample size is relatively small, the outcomes are substantial and encouraging.

Additionally, intensive research has discovered that for every 1 dollar put into this program, 7 dollars are released back into the community.149 This statistic is calculated using verified estimates of expenses that will be avoided since the graduated Friend Youth is avoiding the justice system and has lower healthcare costs among other factors.150 It also measures the financial outcome of their children and grandchildren avoiding poverty.151 Along with the economic return, the social return on investment for the program is 24.6 times more than the initial cost, as this also includes immediate family members, friends, and future generations who are positively impacted by the youth involved.152 A program whose effects continue for generations is a powerful tool to impact the children of the next generation, who would otherwise fall victim to intergenerational poverty.

Gaps

While Friends of the Children is an impactful organization, there are gaps in its practices. One gap is that there is no way to ensure that the children with the greatest need are being helped. Even after a due diligence process, there may still be another child who was struggling quietly or whose parents did not accept this service that might not be admitted into the program. Also, children are only introduced to the mentor program before their second year of elementary school. For students who were not inducted into the program at that time, they would not benefit from any of the services and would not have another chance to have a Friend mentor in their life.

Additionally, there is a lack of data demonstrating the true impact of Friends of the Children on the Friend Youth. While the data on the Friend Youth are indicative of the program’s success, in order to ensure this organization is working to eradicate generational poverty, supporting evidence on long-term effects is necessary. Since the organization has been open since 1993, in coming years a study on the second generation impacted by the program must demonstrate the longitudinal impact on this program. Only with statistics of the second generation’s (children born roughly 2008 to present) poverty rates, incarceration, high school graduation, and teenage birth rates would one be able to confirm whether or not this program has been effective in breaking the cycle of intergenerational poverty and eradicating its negative effects.

Preferred Citation: Monica Privette-Black. “Intergenerational Poverty in the United States.” Ballard Brief. May 2021. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints