Maternal Mortality among Black Women in the United States

By Joli Hunt

Published Summer 2021

Special thanks to Hannah Pitt for editing and research contributions

Summary+

The chance of a Black woman dying in the US due to complications relating to pregnancy or childbirth is 2 to 3 times more than a White woman in the US—a disparity large enough to cause the national maternal mortality rate to increase at a steady rate. Challenges influencing this problem include implicit racial bias within the healthcare system that causes negligence, a lack of standardized healthcare to provide quality care in all parts of the US, and the stress caused by systemic racism and its effect on Black female bodies. Maternal death has detrimental effects on Black families and children by increasing the premature and infant death rate and the amount of motherless Black families. Practices providing external mental and physical support before, during, and after childbirth are best exemplified by local doula organizations such as the By My Side Birth Support Program in New York. Public health policy is also being researched and supported by organizations such as The National Partnership for Women and Families in Washington D.C. to pass bills in support of reproductive care rights and other familial issues in government. California is an example with its recent hospital protocols to prepare for complications during childbirth.

Key Takeaways+

Key Terms+

Eclampsia—A severe complication of preeclampsia. It is a rare but serious condition where high blood pressure results in seizures during pregnancy.

Hemorrhage—Bleeding or the abnormal flow of blood.

Hypertensive disorder—Hypertensive disorders during pregnancy are caused by high-blood pressure preceding pregnancy. These disorders are classified into 4 categories: 1) chronic hypertension, 2) preeclampsia-eclampsia, 3) preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension, and 4) gestational hypertension.

Implicit Bias—Bias that unconsciously affects actions and understandings and can negatively impact individuals in a variety of situations.

Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR)—The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is defined as the number of maternal deaths during a given time period per 100,000 live births during the same time period. The rate depicts the risk of maternal death relative to the number of live births and essentially captures the risk of death in a single pregnancy or a single live birth.

Maternal Mortality—The death of a woman during pregnancy, at delivery, or within 42 days after pregnancy.

Medicaid—A public health insurance program that provides health care coverage to low-income families and individuals in the United States. The program is jointly funded by the federal government and individual states.

Negligence—A failure to behave with the level of care that someone of ordinary prudence would have exercised under the same circumstances. The behavior usually consists of actions but can also consist of omissions when there is some duty to act.

Obstructed labor—When the infant does not exit the pelvis during childbirth due to being physically blocked, despite the uterus contracting normally. Complications for the baby include not getting enough oxygen, which may result in death. Obstructed labor increases the risk of the mother getting an infection, having uterine rupture, or having postpartum bleeding.

Postpartum—Occurring in or being the period following childbirth.

Pregnancy-Related Death—The death of a woman while pregnant or within 1 year of the end of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy.

Prenatal—Occurring, existing, performed, or used before birth.

Sepsis—A potentially life-threatening condition that occurs when the body's response to an infection damages its own tissues. When the infection-fighting processes turn on the body, they cause organs to function poorly and abnormally.

In this issue brief, the term “Black” is used to refer to an individual of African descent whose race is classified as “Black.” This reference includes both Hispanic and non-Hispanic ethnic backgrounds. The term “White” refers to individuals whose race is classified as “White” and do NOT have Hispanic ethnicity or nationality. Use of these terms corresponds with how terms are used in referenced studies.

Context

Maternal mortality is defined as the death of a woman during pregnancy, at delivery, or up to a year after delivery.1 The most common causes of maternal death include hemorrhage, eclampsia, obstructed labor, and sepsis.2 Maternal mortality is measured by maternal mortality rate (MMR), which represents the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 pregnancies. The ideal MMR rate for a country is 0, meaning no maternal deaths. The countries closest to this ideal are Belarus, Poland, Italy, and Norway, all with an MMR of 2.3 The countries with the highest MMRs are typically lower-income countries where quality healthcare services are limited or inaccessible to those living in poverty.4 In contrast, higher-income countries usually have lower trends of maternal deaths, with the exception of the United States.

The rate at which mothers are dying in the US is quite high, and has notably increased since 1990 while most other high-income countries have seen decreases in their maternal death rates.5 The National Centers for Health Statistics (NCHS) released a national MMR report for the US in 2007, at which time the maternal mortality rate was 12.7 deaths per 100,000 pregnancies.6 Since then, the rate has continued to increase steadily each year.7

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) currently ranks the US 50th for maternal mortality,8 with a higher mortality rate than the majority of European countries as well as Saudi Arabia and Russia.9 With 2018 data revealing an MMR of 17.4 deaths per 100,000 pregnancies, the US has the highest maternal mortality rate of the top 10 developed economies in the world and is also the only newly industrialized country with a rising MMR.10

The study observed increase in MMR in the US is partially due to better surveillance and reporting of maternal deaths over the last several years. The MMR in the United States has always been relatively high compared to other countries; better data gathering methods, such as reviewing and analyzing death records, has simply shed light on the gravity of the maternal death issue. The data collected from this type of surveillance is used to estimate the number of maternal deaths in the United States. Gaps in numbers due to computer data errors were found in early reporting but have improved since then. With recent data, we know that deaths of Black women make up the largest portion of overall maternal deaths, increasing the national MMR and highlighting the depth of systemic racism in the US.11

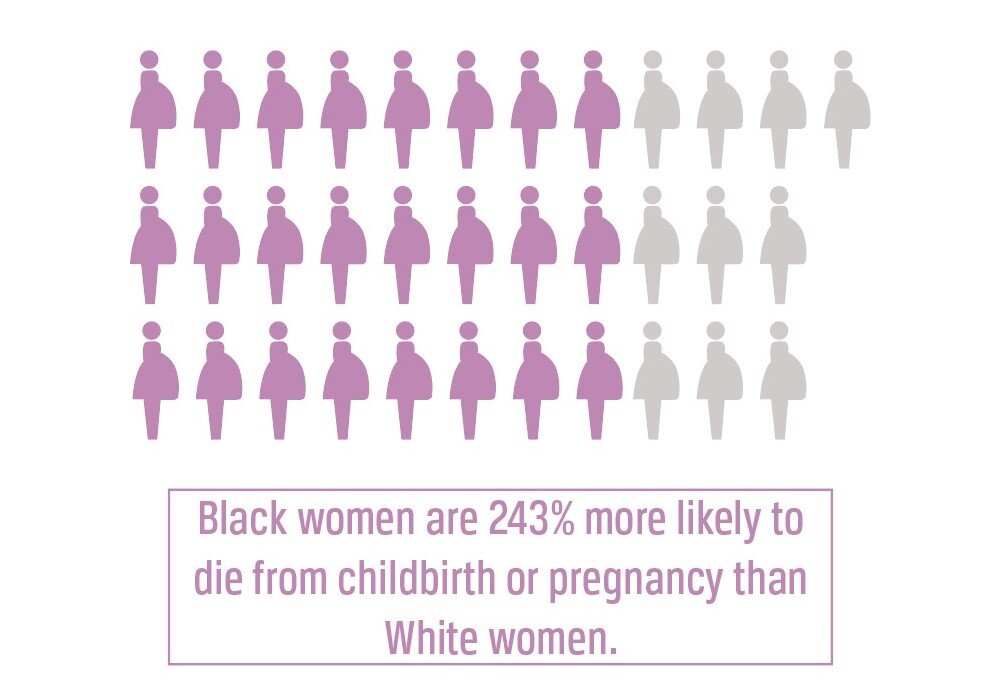

A 2014–2016 national study on pregnancy-related deaths in the US concluded that Black women have an average maternal mortality rate of 41.7 women per 100,000 pregnancies, compared to White women who average 13.4,12 making the maternal death rate for Black women 243% higher than for White women. The MMR is higher among Black women as compared to White women irrespective of age or socioeconomic status, although Black women of low socioeconomic status do have a higher MMR than Black women of high socioeconomic status. The common causes of maternal death among Black women are hemorrhage, infection, and hypertensive disorders such as eclampsia.13

The distribution of maternal deaths across the nation displays the connection between high MMR and Black women. The Southern United States has the highest regional mortality rates, ranging between 34.1 to 58.1 deaths per 100,00 pregnancies, compared to the western US and New England states whose MMR rates are all below 30 deaths per 100,000 women.14 This trend is significant, since 58% of Black people in the US live in the southern region of the country.15 Since there is a higher concentration of Black women in the Southern US and the maternal mortality rate is higher in this region, it can be inferred that the maternal mortality rate among Black women is higher in the Southern US than in other regions of the country.

Although maternal mortality is classified as a top priority by world leaders and policy makers, these statements are often not translated into definitive action.16 Foreign governments and international aid organizations tend to view maternal death as a “normal death” that is not as easily preventable compared to events where mass casualties take place such as HIV/AIDS outbreaks, civil war and ethnic conflict, and other humanitarian crises. Resources are typically diverted to these types of situations first. Many scholars and political leaders struggle to commit equal resources to combating both humanitarian crises and maternal mortality. World leaders find justification in data that suggests peace and security need to be accomplished first before prevention of maternal mortality can be addressed given that reducing mortality requires both peace and security as well as significant investments in health, education, economic development, and women’s rights.17

Contributing Factors

Racial Bias in Health Care

Racial bias in the US healthcare system contributes to disproportionately high maternal mortality rates among Black women. This racial bias is often implicit, meaning it is unconsciously held and affects the behavior of healthcare workers without them being cognizant of it. Negligent treatment is often based on preconceived racist ideas about the biological makeup of Black people’s bodies, such as the ability to be more athletic (the belief that they are stronger and faster than White people), that they have stronger bones, thicker skin, stronger immune systems, and a significantly higher pain tolerance than their counterparts of other races. In health care, racial bias has been found to cause medical negligence in the form of underdiagnosing illnesses, disregarding complaints of pain, and not fully addressing the symptomatology of an illness.18 Researchers postulate that the racial disparities in pain management could be explained by the possibility that physicians recognize pain levels of Black patients but do not treat them, or that they do not recognize pain levels of Black patients and therefore cannot treat the patient properly.19

This inherent bias extends to prenatal and postnatal care for Black mothers. Inherent bias can lead health care providers to disregard the complaints of pain from Black mothers at a higher scale, perpetuating medical inaction at times mothers need focused care and assessment. Additionally, providers may make incorrect judgements about pregnant Black women’s bodies as to how much pain they can handle and which medications to give them during pregnancy, during labor, and postpartum.20 Since the 1980s, the Black/White maternal death disparity has been blamed on Black mothers, their life choices, and their socioeconomic situations, instead of studying underlying causes of disease such as stress and poverty. Black women have shared stories about their experiences when medical providers associated them with “being poor, uneducated, noncompliant and unworthy.”21 With these associations come reluctance to believe what the patient is communicating to the healthcare workers, and therefore treating them incorrectly or not treating them at all. There are many publicized reports of Black mothers being ignored when stating concerns over their health before, during, or after childbirth, including the high-profile case of Serena Williams who developed a pulmonary embolism after the birth of her child and was initially disregarded by the nurse when she asked for help.22 Though this is anecdotal, there are many other reports by Black mothers stating their concerns were not taken seriously when they reported experiencing symptoms that could indicate fatal conditions.23 Erroneous treatment or lack of treatment can result in dangerous pregnancies and childbirths and ultimately death.

Chronic Stress from Systemic Racism

Systemic racism in the United States affects the health of Black women, making them more susceptible to diseases and complications before, during, and after pregnancy. Researchers have linked the stress that Black women endure from chronic, racist experiences with pregnancy complications.24 In a 2017 poll, 92% of African Americans living in the US stated they experience and believe that racial discrimination is still prevalent in the US.25 Because systemic racism is a major and constant stressor in the lives of Black women, they are at a higher risk for stress-related diseases such as hypertension and preeclampsia. Researchers speculate this is due to premature aging caused by traumatic events over the course of a lifetime.26

Researchers use the term “weathering” to describe the negative effects of prolonged stress on the Black female body. Physiologically, prolonged stages of stress can stimulate an overproduction of the primary stress hormone, cortisol.27 High cortisol levels lead to many negative effects, including higher blood glucose levels, weight gain, chronically high blood sugar, rapid heart rate, and immunosuppression. These negative effects are heightened the longer high levels of cortisol are in the body.28 Women who experience weathering already have higher risks of developing health issues, many of which can progress to problems such as gestational diabetes, eclampsia, and infection when the woman is pregnant.29 This weathering contributes to higher MMR among Black women in the United States and explains the reason why maternal death affects Black women in a variety of socioeconomic situations.30 For example, a Black mother who graduated from college and gives birth in a hospital is more likely to die from childbirth than a White woman who did not finish high school. This is in part due to the inescapable stress that the Black woman encounters with racial discrimination.31 Stress from discrimination is experienced by Black women throughout the US, regardless of age, education, or status.

This link between stress caused by racism and maternal mortality is essential to eliminating victim blaming. Understanding the effects of stress on a pregnant woman's body when it comes to disease and death demonstrates how external factors of society are causing disease and death rather than lifestyle choices or controllable factors among Black mothers.

Lack of Access to Health Insurance

The health care system in America is not equally accessible in all regions and among all individuals, which contributes to the lack of maternal care received by Black women. As of 2019, 14% of Black women in the US were uninsured, compared to 8% of White women. Systemic public health inequalities such as poor Medicaid expansion in the Southern states and health care provider shortages make it more difficult for Black women with a low income to have health insurance.32 Black women of reproductive age (15–44) face the biggest coverage disparity, which is especially notable since these women are in highest need of preventative healthcare such as birth control and other family planning methods.33 If a woman of poor health knows that she could not safely undergo a pregnancy, birth control is vital for her to protect herself from an unwanted, potentially dangerous pregnancy. Since Black women have less health insurance coverage and thus less access to birth control and other family planning education and resources, they are more at risk of dangerous pregnancies that can increase their risk of maternal complications and/or death.

Lack of access to affordable insurance also hinders a woman's ability to receive adequate pre- and post-natal health care. Medicaid is used by 25% of Black women in the US and 55% of Black women are provided with insurance through their occupation.34 The alternative to these two resources of insurance is paying individually through insurance markets or with private insurance, where the quality of care is almost directly based on the amount of money you can afford to put towards health insurance.

In 2012, 25.8% of Black pregnant women were covered by private health insurance, compared to 48.1% of White women.35 Private insurance is typically of better quality than public insurance, meaning patients have access to a breadth of medical treatments such as checkups, prescriptions, and surgeries. Public insurance limits access to treatments because it does not cover costs for as much as private insurance does.36 Thus, Black mothers who cannot afford private insurance lose the opportunity to receive the best medical treatment and have a higher risk of maternal death.37

Impoverished Living Conditions

In 2019, about 16.6 million Black women were living in poverty in the US, while the number of White women in poverty was 8.8 million.38 The environmental conditions that women in poverty face contribute to a high MMR among women worldwide and in the US and make it challenging for Black women to have safe, healthy pregnancies.

During the Jim Crow era in the US, lasting from the post-Civil War era until the late 1960s, government resources were distributed unequally on the basis of racial separation, resulting in unequal access to housing, education, healthcare, and other resources.39 Though the Civil Rights Acts attempted to end unequal treatment, this period of history resulted in a disproportionate amount of Black women in poverty with restricted access to the resources necessary to reduce their risk of disease and death during pregnancy and childbirth.40 Racially segregated neighborhoods tend to receive less economic investment, limiting access to higher quality housing, education, and holistic healthcare.41 In 1960, there were 18 hospitals in the predominantly African American neighborhoods in St. Louis housed; however, closures left only 1 in 2010. Similarly in Detroit, 42 hospitals existed in Black neighborhoods in 1960 but in 2010 there were only 4 left. These are examples of a broader trend of fewer hospitals and clinics in Black neighborhoods across the country.42 Additionally, overcrowded bus systems and underfunded transportation systems inhibit access to the few hospitals and clinics that do exist in low-income and Black neighborhoods.43

Given the limited numbers of hospitals and healthcare services in poor neighborhoods, regular doctors appointments are not being scheduled or completed due to under-availability of these appointments in low-income Black communities. As a natural consequence of inconsistent doctors appointments, people in these neighborhoods lack education about healthcare options and resources available to them and their family members. This lack of education can prevent Black mothers from understanding necessary practices during their pregnancy and childbirth. Without knowing the importance of prenatal care, an expecting mother may face serious consequences for herself and her child.44

Another challenge faced by communities of color is restricted access to healthy foods. Studies in the US from several major cities found that predominantly African American neighborhoods had fewer options for healthy eating (such as supermarkets and farmers markets) and that unhealthy fast food was heavily promoted. Even affluent African American neighborhoods showed higher promotion of unhealthy food, relating unhealthy food with race association over socioeconomic status.45 A poor diet can result in obesity, diabetes, and other diseases that heighten the risk of complicated pregnancies and thus maternal mortality.46 Without access to nutritious food in their communities, mothers may struggle to nourish themselves sufficiently, which can cause issues in their pregnancy and childbirth and lead to increased risk for maternal death.

It is important to understand the cyclical consequences of poverty for Black women in the US. For example, a lack of resources for Black mothers heightens the risk of maternal complications, which ultimately results in high medical bills for the family, or in worse cases, funeral costs if the mother dies, pushing the family further into poverty.

Consequences

Increased Infant Mortality and Health Complications

Highest among Black babies, infant mortality parallels maternal mortality trends in the United States.47 In 2018, the Black infant mortality rate in the US was 10.8 for every 1,000 births, more than twice the rate of White infants.48 The CDC defines infant mortality as the “death of an infant before his or her first birthday.” Because Black women die in childbirth at a 243% higher rate than White women, the risk for infant death is significantly higher for Black infants than White infants. "Children whose mothers died during or shortly after childbirth were at approximately 50 times greater risk of dying during the first month of life than babies whose mothers survived."49 These statistics indicate a correlational relationship between maternal mortality rates and infant mortality rates.50

A multinational study on fetal deaths found the risk of infant death and stillbirths was significantly increased by maternal complications.51 The most prevalent complications include infections/sepsis, pre‐eclampsia, eclampsia, and severe anaemia.52 These complications also increase the risk of maternal death, indicating that if a woman is more likely to suffer death from pregnancy complications, the risk of her infant dying is also significantly higher. Early identification of these complications most often occurs during prenatal care.53 The quality of prenatal care received also affects the probability of babies surviving. Lower-quality prenatal care is believed to be a reason why Black women who received prenatal care in the first trimester still had a higher chance of their baby dying than White women who received little to no prenatal care.54 With access to quality prenatal care, the risk of maternal complications would decrease, thus decreasing the risk of maternal death and in turn reducing the risk of infant death.

Preterm births are the leading cause of death among children under the age of 5. A preterm birth occurs when babies are born alive before 37 weeks of pregnancy, resulting in developmental disabilities and complications.55 Premature birth is more common among Black women than among any other race in the US. A case-control study among 104 African American women compared the effect of racial discrimination before and during pregnancy to preterm birth rates and the health of the mothers. Women who reported discrimination in the workplace or while finding a job had the highest probability of having a child with a very low birth weight due to stress-related diseases. The study concluded that the effects of racism on Black women are a chronic stressor that leads to the early delivery of their children at rates significantly higher than White women.56 Stress hormones are already high in full-term labor, but chronic stress can lead to a hormonal spike in pregnant women, causing complications during pregnancy, increased risk of death, and possible preterm delivery (which then increases the risk of infant mortality).57

Adverse Effects on Motherless Black Families

In 2019, there were 472,000 Black families living with a single father in the US. 58 While the percentage of these families who suffered the loss of a mother due to pregnancy-related complications is unknown, the high MMR rates among Black women indicate that a large number of families in the US are vulnerable to the negative effects of such losses.

The consequences of maternal mortality affect fathers, children, and other family members. The death of a mother comes with high medical and funeral costs; without federally paid parental leave, it is difficult to cover these costs.59 In the absence of a mother, a single father must take on the responsibilities of two parents. He must provide financially while also caring for a new infant (if the infant survived) and possibly caring for additional children. Approximately 74% of African American women consider themselves the “breadwinner” of the family, placing significant financial stress on the remaining family members in the case of their death. The death of a mother also distributes new and burdensome responsibilities to siblings and extended family regarding the care of the children, if the family is fortunate to have family members available to help.60 If not, this gap can lead to increased labor for both the siblings and the father to make ends meet for the household.61 The loss of a mother can also result in malnutrition and poor health because caretakers are occupied working and cannot be around to make regular meals nor provide care for injury or illness.62

Losing a family member can also have severe mental and emotional consequences. For young children, it can affect their sense of security as they may not understand how to navigate their feelings about losing a parent.63 Long term effects of parental death are depression, anxiety, and substance abuse.64 Similarly, spouses and other family members can experience depression during and after the grieving process.65

Some children may be left without either parents if their mother dies in childbirth or pregnancy—4.15 million Black families in the United States were single-mother households in 2019.66 If a single mother dies, her children are left parentless and become the responsibility of family members or become wards of the state government.67

Practices

Doulas

A common practice to help decrease the risk of maternal mortality among Black mothers is hiring a doula. A doula is “a trained professional who provides continuous physical, emotional and informational support to a mother before, during, and shortly after childbirth.”68 Doulas assist in childbirth in any location, whether it be at a hospital with doctors and medical staff or at home with a midwife. Doulas do not replace a medical professional; rather, they exist to provide ongoing support and education to the mother outside of the place of birth. They also advocate for women by communicating with doctors, helping women understand their options, and supporting them in their decisions.69

Having a doula present for a birth can reduce labor time, reduce risk for cesarean section surgery, and improve infant health. However, doula services average $800 to $2,500 per birth, and most insurance companies do not cover these costs.70 Access to quality resources like doulas can be scarce among women of color and low-income women, and therefore there is no data supporting the improvement of doula care for Black women specifically.71

There are many programs that focus on providing quality doula care to underserved groups. One example is the By My Side Birth Support Program based in Brownsville, New York City. It has a unique combination of community-based programs and private doula practices to provide free doula support to pregnant women living in low-income neighborhoods. These neighborhoods have disproportionate percentages of obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes that can be linked to inadequate healthcare and unhealthy living conditions.72 The doulas provide prenatal and postpartum services in addition to birth education and support. They help families navigate hospital environments and procedures while communicating with doctors and nurses. They also assess risk factors, give counsel on parenting and child care, and provide other sources of information.73 Doulas can also “reduce the impacts of racism and racial bias in health care on pregnant women of color by providing individually tailored, culturally appropriate, and patient-focused care and advocacy.”74

There is an expressed need for research regarding doula practices and outcomes, specifically in communities of color that have large rates of chronic disease and cesarean births. Because the By My Side Birth Support program is small and has a small budget, there is little room for research between training costs and doula wages.75 Given adequate resources, the program could collect and publish detailed data on maternal and infant health to understand the effects of doula care on each individual.

Other organizations working to close the Black/White maternal mortality gap exist but also have little impact data. The Birthmark Doula Centers in New Orleans is a small group of doulas aimed to provide a variety of birth techniques and support for women of color. The focus of the Birthmark Doula Centers is to create a safe experience for the patient using techniques that they have chosen. They offer childbirth education, a birth doula, postpartum doula services, and lactation support. While they only serve the New Orleans area, their model is a great example of a grass roots collective aiming to reduce Black maternal deaths.76 The National Black Doula’s Association is another organization that works to pair Black birthing families with Black doulas. They provide a directory to aid in that process, and well as doula training and education all for the purpose of reducing Black maternal mortality.77 Both of these organizations are great examples of bottom-up solutions to the high Black MMR rate.

Public Health Policy

Many Black mothers that live in poverty do not have access to affordable, quality health care, which can increase their risk of dying due to pregnancy or childbirth-related factors. Solutions have been pushed by NGOs and nonprofits who lobby for policy change and protection regarding Black women’s reproductive rights and affordable health care.78 Policy is the key to eliminating discrimination and providing opportunities for minorities through government regulation.

The National Partnership for Women and Families is a nonprofit 501(c)3 organization based in Washington, D.C. The partnership works in four main areas: health care, reproductive rights, workplace fairness, and family friendly workplace policies. They focus on building support for and passing bills in Congress related to these areas. They conduct research that provides resources to the public on women and their access to health care entities in order to enact laws such as the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, the Civil Rights Act of 1991, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, the Family and Medical Leave Act, and statewide family leave programs.79

Great research is conducted and recorded by the National Partnership on the environmental, social, and political effects of policy on women of color. They conduct surveys and publish articles that act as persuasive information in support of bills to be passed in Congress.80 However, the National Partnership does not measure how populations are benefited after bills are passed, meaning that the true impact of this organization and of these changes to public policy in decreasing maternal mortality is unknown.

Other projects working to change public policy that affects Black mothers are the Doula Medicaid Project and the Black Mamas Matter Alliance. The Doula Medicaid Project is a branch from the National Health Law Program—a program formed by a group of lawyers working to litigate on a state and federal level for the health care rights of low-income and minority individuals. Direct impact measurement on the Doula Medicaid Project has not been performed, but the project has introduced and is working on over 25 bills in different states regarding the inclusion of doula care for Medicaid enrollees.81

The Black Mamas Matter Alliance, a “Black women-led cross-sectoral alliance,” focuses on researching and implementing ideas to improve the reproductive rights of Black women. They have goals to change policy, provide research to leverage that policy, provide the best care for pregnant Black women, and to be the voice of Black mothers everywhere. Like the Doula Medicaid Project, impact evaluation is not published. However the Black Mamas Matter Alliance provides toolkits for activists in the South who advocate for maternal health, holds events such as “Black Maternal Health Week,” and is continuously doing both quantitative and qualitative research.82

Hospital System Preparation

Reconstructing the way that hospitals approach maternal mortality could save the lives of thousands of black mothers in the US. California has recently become an example for the rest of the nation for their effective approach to reducing maternal deaths in hospitals. From 2006 to 2013, the MMR in California dropped 55% after implementing new protocols to combat preventable deaths by hemorrhage and preeclampsia—two of the most prominent preventable causes of maternal death in California hospitals.83 These protocols are the makings of the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative, a “multi-stakeholder organization committed to ending preventable morbidity, mortality, and racial disparities in California maternity care.” Committees of the collaborative produced special “toolkits” that contained all the supplies necessary in the event of complications during childbirth, as well as written articles and guidelines to educate hospital staff.84 Doctors also began special training for nurses on how to use these toolkits and ran role-play scenarios to prepare for anything that could go wrong in the event of childbirth. Over 88% of California’s hospitals have implemented the use of toolkits to reduce their maternal mortality rate; however, this toolkit is too recent to gain adequate impact data. This practice has much potential but will need to be monitored closely to determine whether the actual impact lives up to the potential impact it could have.

Preferred Citation: Joli Hunt. “Maternal Mortality Among Black Women in the United States.” Ballard Brief. July 2021. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints