Lack of Access to Quality Healthcare in Peru

By Spencer Hart

Published Winter 2021

Special thanks to Kaytee Johnson for editing and research contributions

Summary+

The current healthcare systems in Peru leave millions without easy access to medical attention, many of whom are also living in poverty.1, 2 It is difficult for the governing bodies to include everyone in healthcare coverage plans and make the necessary medical resources accessible.3, 4 The lack of qualified medical professionals, in part due to a migration of doctors out of the country to seek better opportunities elsewhere, also contributes to the problem.5 As can be expected, these and other factors lead to greater amounts of illness and deaths than other countries that have more developed healthcare.6 These problems have also caused a decrease in the confidence Peruvians have in healthcare professionals and modern medical systems, with many often turning to less effective traditional practices instead.7 Several organizations are working to help solve this social problem, with the best of them working on administering healthcare to the vulnerable, building connections between modern and traditional medicine, and providing much needed medical supplies.

Key Takeaways+

Key Terms+

EsSalud—EsSalud is Peru’s equivalent of a social security health program funded by payroll taxes paid by the employers of sector workers.8, 9 Although not free, the cost of EsSalud is much cheaper than private healthcare options.10

Seguro Integral de Salud (SIS)—Translated as Comprehensive Health Insurance, this is a government program that provides free health insurance to those living in poverty and extreme poverty.11

Rural—All populations, housing, and territories not included within an urban area.12

Urban—A place that comprises a city or town and also the suburban fringe or thickly settled territory lying outside.13

Primary care—The provision of health services, including diagnosis and treatment of a health condition, and support in managing long-term healthcare.14

COVID-19—A highly contagious respiratory disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.15

Traditional medicine—The sum total of the knowledge, skill, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness.16

AIDESEP—The Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest is a Peruvian national indigenous rights organization, presided over by a decentralized National Council.

Context

While more and more Peruvians have gained access to healthcare since the turn of the century, millions still lack basic healthcare.17 The current healthcare systems in place lead to a significant disparity in quantity and quality of medical coverage and access to life-saving healthcare. The percentage of Peruvians with healthcare coverage ranges greatly in its different provinces, the lowest being the Tacna province at 66% and the highest being 93.4% in the Amazonas province.18

Healthcare in Peru is divided into several subsets. First, some companies provide private care and facilities. These resources, most similar to private insurance companies many in the US are familiar with, are not highly utilized in Peru and will not be the focus of this brief. Public healthcare, on the other hand, is provided through 2 different programs. Salary workers gain access to the public healthcare system EsSalud through their employment. However, according to the World Bank, only 45% of Peruvian workers are salaried.19 The other 55% of the population can either pay for coverage themselves through EsSalud or private companies, or they can qualify for the public healthcare provided by the government specifically for the impoverished.20 This government program is called Seguro Integral de Salud (SIS), which means Comprehensive Health Insurance, and is focused on providing healthcare access to the impoverished population and charges a quota (copay) for the treatment received.21 Recently, the number of people relying on SIS has grown significantly; in 2008, 18% of the Peruvian population was covered by SIS, while in 2017 it was reported that 44% of the population was insured through SIS.22 Even with these increases in coverage, 10–20% of the Peruvian population remains excluded from basic healthcare access without public or private coverage.23

Because the government is rapidly seeking to expand to universal coverage, the quality of provided healthcare in Peru is often lacking. Physicians and facilities often do not have adequate resources for all the individuals they are trying to provide for. The number of available hospital beds has a substantial impact on mortality rates and can indicate the strength of a country's medical infrastructure.24 In 2014, Peru reported roughly 16 hospital beds for every 10,000 people compared to the 29 in the United States and 22 in neighboring Chile.25 The number of licensed physicians per 1,000 people were nearly the same as the number of hospital beds in each of these countries according to 2016 data.26 These various ways that healthcare is falling behind result in one of the most obvious indicators that the healthcare system is struggling—wait times to receive critical care that can be so long that they put patients’ lives in danger.27

To better understand the healthcare struggles within Peru, it is important to be familiar with the situation of those living there. There were an estimated 32.5 million people living in the country of Peru at the end of the year 2019.28 Peru is divided both culturally and socioeconomically into two regions: rural and urban. According to a recent census report, approximately 75.9% of the total population lived in urban centers, while the remaining 24.1% lived in rural areas.29 There are large economic inequalities in Peru, with 20% of the population controlling over 54% of the country’s income.30 Roughly 50% of the population lives in poverty, subsisting on about USD $3.10 daily,31 and 20% live well below the poverty line, living on roughly USD $1.90 a day.32

While urban areas have greater access to quality healthcare than rural areas, both rates remain low—16% of Peruvians living in urban areas had access to high-complexity medical centers while 5% of Peruvians in rural areas had access to medical facilities of the same quality.33 Both rural and urban areas experience a lack of high-quality healthcare with the most extreme differences in the poorer sectors of the nation. The data produced by the Peruvian Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (National Institution of Statistics and Information) show that far fewer women in the poorest sectors of the country are being assisted by health centers while giving birth.34 In a recent Census of Indigenous People, “59.1 percent of rural communities did not have any health facilities, 45.4 percent had only a first aid post, 42.3 had only a basic healthcare facility and 10.9 percent had a health center (handles more than a basic health facility).” Existing problems are worse in these extremely poor areas and impoverished women who face complications with pregnancy are at an increased level of risk, and face little to no chance of survival due to the distance of adequate care.35

Contributing Factors

Insufficient Health Coverage

As the government seeks to rapidly expand to universal healthcare coverage with limited resources, access to healthcare in Peru is restricted due to problems acquiring health coverage as well as insufficient services for those who are covered. Due to a variety of limitations within the healthcare system’s infrastructure, between 10–20% of the Peruvian population is completely excluded from the services and facilities of the Peruvian healthcare system.36 In Peru, some of the limitations the healthcare system faces include producing trained human resources in sufficient numbers, managing financial resources, improving governance, quality of care and communication, and expanding coverage of the public health system.37 There is much more that could be said about each of the challenges the Peruvian healthcare system is facing, but their combined consequences are limiting the population’s access to quality healthcare.

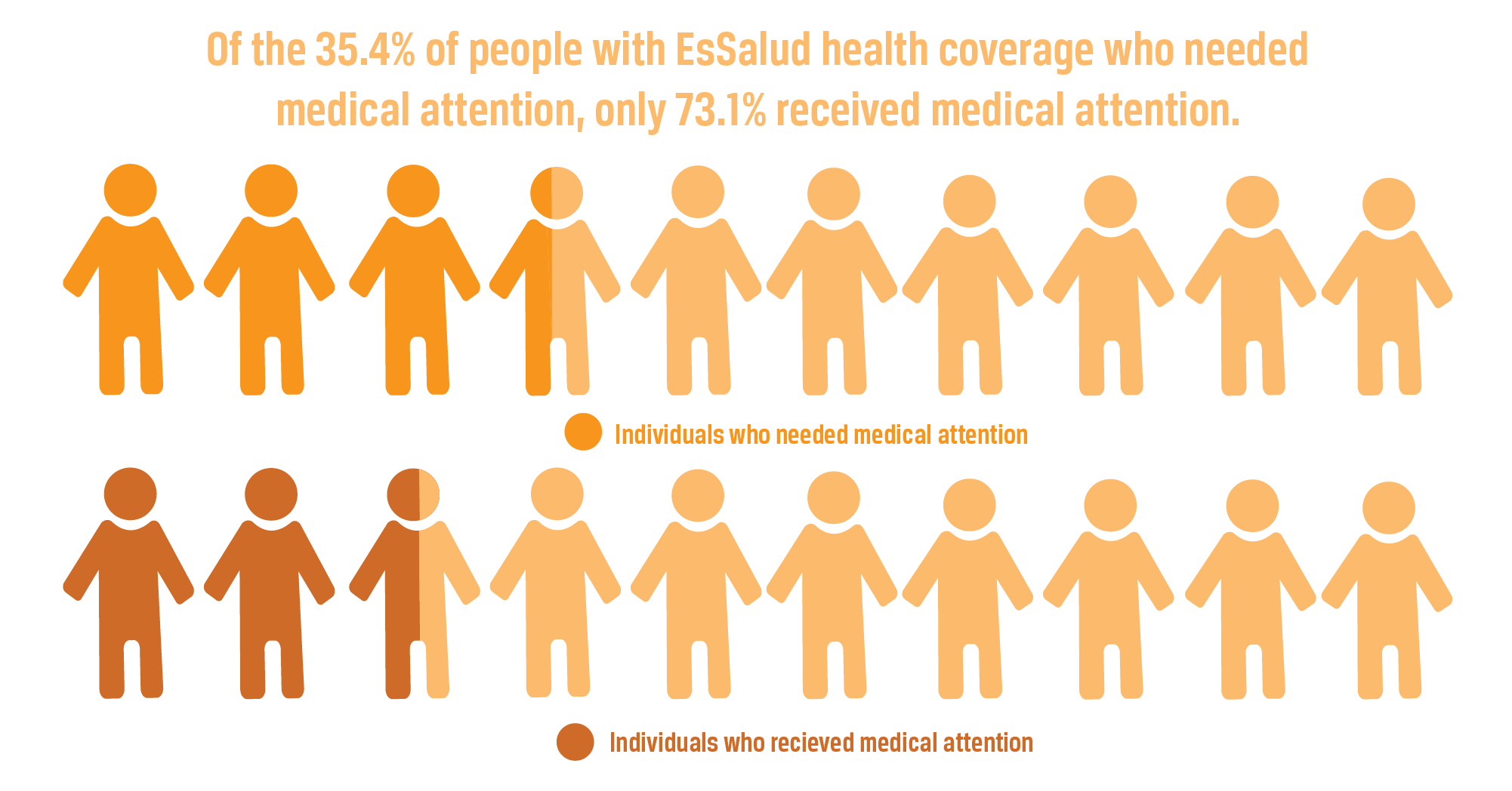

The percentage of Peruvians who do have access to healthcare is growing, which is placing a strain on the current healthcare system. In 2008, EsSalud was providing coverage for 20% of Peruvian citizens. In a recent survey of those insured by EsSalud, it was reported that in the last 3 months, 35.4% of the EsSalud members needed medical attention. Of these, only 73.1% received healthcare.38 Principle Responsibility for providing healthcare is slowly transitioning to be a government responsibility, and currently there are many individuals who are not receiving adequate healthcare as a result. While the government seeks to eventually provide universal coverage, in the meantime overloaded healthcare facilities and workers fail to address the medical needs of many, even some with health coverage.

SIS aims to protect the health of Peruvians without health coverage, prioritizing the vulnerable population that is in a situation of poverty or extreme poverty. SIS is 94% funded by the Peruvian government, which allocates USD $332 annually per capita for healthcare. This is much lower than countries in the same region; for example, Chile and Argentina allocate roughly $1,300 per capita for healthcare.39 The governing body that directs the use of these funds is weak and doesn’t regulate or inspect health establishments regularly.40 Families and individuals qualify for SIS based on their economic level. With so many families in poverty, SIS lacks funding to cover all families in extreme poverty.41

Accessibility of Physical Resources

Contributing greatly to Peru’s healthcare challenges is the extreme deficiency of physical medical resources such as medical facilities, hospital beds, medicine, tools, and equipment. In a country of 31 million people, there is only one pediatric hospital, which is found in Lima.42 In the United States there are 29 hospital beds per 10,000 people. In Peru there are 16.43 In countries with even better infrastructure, such as Japan, there are as many as 130 hospital beds per 10,000 people.44

Because the national health system is stretched so thin, doctors at primary health facilities in rural Peru have limited access to diagnostic tools and adequate funding. This causes doctors to face challenges in diagnosing patients accurately.45 To illustrate this, during a leptospirosis outbreak in 2013, 90% of the patients were incorrectly diagnosed and treated for dengue because of their similar symptomatology. A month went by before the test results came back from Lima and medical professionals could react.46 In the United States, these test results come back anywhere between 4 days and 2 weeks after being tested.

The lack of control over the distribution and sale of medicine in Peru makes acquiring needed medication difficult and sometimes impossible. It is estimated that 50% of Latin America has little to no access to medicines and 66% of the medicine purchased is paid for entirely out of pocket by the patients.47 In Peru, 43.3% of those in moderate to extreme poverty reported that money was a barrier to accessing medical care.48 For example, almost half a month’s salary would be needed to treat a urinary tract infection with originator brand medicine.49 Even though there are likely more affordable generic options available, this example is simply meant to highlight how unreasonable medication prices can be. To prevent the exploitation of distressed patients and their families, the government has established a price list for common medicines and fixed a 25% profit for the vendors, although it has proven difficult to supervise and ensure this profit margin is not exceeded.50

Those in poverty qualify for government-funded healthcare and also qualify to receive medicine at no cost, but hospitals in Peru are so underfunded, and the process is so lengthy and bureaucratic, that many patients opt to pay large out-of-pocket expenses to avoid wading through the system for needed medicine.51

Lack of Trained Healthcare Providers

Lack of Medical Training

Medical training in Peru is not standardized and is often insufficient, making it difficult for Peruvians to receive quality care. Many physicians have a negative perception of the medical training they received.52 Of the physicians who received their residency training in Peru, 77% reported that the research opportunities, areas of tutoring, and academic activities on average were deficient.53 Furthermore, 82.5% believed that residency should last at least four years, although less than a third of the respondents were actually residents of a four-year program.54

Health professionals at the training/graduate stage lack preparation to work at the primary care level; specifically, they often lack skills related to prevention, health promotion, and health management.55 Of the 298 credits required to graduate from medical school, on average only 4–11 of the credits are related to primary care, which is what most of the medical students will specialize in.56 In 2013, Peru had 21 medical schools and 35 nursing programs, 70% of which were privately owned and not accredited.57 Lack of standardized vocational training and inadequate financial incentives lead to an inconsistency in the quality of care a patient is provided, as well as increased possibility of malpractice.

Lack of Healthcare Providers

Peruvian healthcare is further hindered by the fact that there are simply not enough trained healthcare professionals per capita in Peru. At the national level, the availability of health professionals was 12.2 physicians and 12.8 nurses per 10,000 people. Urbanized areas had 33.1 professionals per 10,000 population, while rural areas had only 17.6.58 In comparison, there are 26 physicians and 140 nurses per 10,000 people in the United States and 26 physicians and 133 nurses per 10,000 in neighboring Chile.59

This shortage only continues to worsen as doctors in Peru are migrating to find better salaries. A 2007 survey showed that interns in the National University in San Marcos, Lima on average expected a monthly salary of $2,600. The average monthly salary for a doctor in Lima at the time was only 25% of that.60 In 2014, 30% of the physicians surveyed reported plans of migrating to another country, exacerbating the shortage problem.61 Because of this shortage of healthcare providers, hospitals become overcrowded, day-long lines are formed at clinics, and wait times to receive treatment become critically long.62

In urban areas, patients may have to wait up to 40 days in order to consult with a physician and when surgery is required waiting times for the operation can be up to 60 days.63 With such a high demand for healthcare and limited availability, many Peruvians are unable to receive treatment for urgent conditions. According to a study in Chiclayo, “When the waiting time to receive the required medical care exceeds the established limits . . . the costs of the [procedure] increase, the risk of complications increase, the disease is prolonged or worsened, and the recovery of the patient is delayed.”64 Longer than acceptable wait times put a strain on the patient, often both financially and in their health.

Consequences

Lack of Confidence in Healthcare

Families in Peru are increasingly distrustful of healthcare. From experiences with extreme wait times in overcrowded healthcare facilities to malpractice, many believe that doctors do not have their best interests in mind. After gathering data on the experiences of many Peruvians, researchers created an example of what a typical Peruvian seeking treatment for diabetes may go through.65 They found that the experience would likely involve travel times of 2 hours via public transportation to a facility with the proper diagnosis equipment to schedule an appointment for 10 days later. Upon return to the medical facility, wait times of around 2 hours would be expected before a 15-minute consultation with a physician. Most of that time is used to fill out forms which allows very little time to ask questions and be heard. A return appointment would be scheduled for 3 months in the future, a prescription for anti-diabetic drugs would be given along with a list of required laboratory tests. After the physician consultation, the patient would go to the laboratory and be told to return in 2 days for their tests. Now home and discouraged, the patient would seek counsel from their local community health center and receive contradictory recommendations by the staff untrained in diabetes management. Eventually the patient would stop taking the prescribed medication and return to their previous lifestyle, worsening their condition and damaging their confidence in the healthcare system’s ability to properly manage their health.66

With extreme wait times and the danger of malpractice, many Peruvians decide to forego medical attention in hospitals and use culturally traditional medicinal practices. Peru has more native plant species with known properties utilized by the population than any other country in the world, and this has had a great impact on how they treat illnesses, even today.67 Traditional practices go beyond the use of herbal medicine; roughly 20% of Peruvians undergo particular practices such as pasada de huevo y pasada de cuy, a ritual involving moving an egg or guinea pig around the body which is believed to extract illness or show where illness is concentrated in the body rather than pursuing western medical care.68 Others visit hueseros, or bone doctors, rather than waiting for postponed surgical operations. These practices are common in both rural and urban areas. The 45% of the population who are indigenous are often not accustomed to modern medical practices, and the modern medicine they do interact with in Peruvian facilities is often less than adequate.69 It is difficult to enable these citizens with an ability to understand the importance of implementing new techniques while balancing their reliance on sometimes inaccessible modern pharmaceuticals, and they are often left with, overall, insufficient care. Although there are varying opinions on the effectiveness of both traditional and Western medicine in Peru, the danger of confidence lost in the medical system is that patients are often left without medical treatment.

Public Illness

The lack of adequate healthcare in Peru causes an increase in public illness. In the rural areas of the nation, treatment for serious tropical diseases such as dengue and malaria are postponed or neglected. A study that was conducted in the Amazon city of Iquitos confirmed that due to lack of proper medical attention individuals who received subpar treatment for dengue—a mosquito-borne illness that can spread quickly—were faced with educational and financial challenges as they missed extra time away from school and work,70 whereas the prevalence of non-communicable diseases in populations in poorer urban areas is disproportionately high.71

The Peruvian Ministry of Health (MINSA) lacks focus on the prevention and management of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and cancer. Under MINSA’s standards, nurses are only required to treat patients with communicable diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS, and all the responsibility of preventing and treating non-communicable diseases falls on the shoulders of physicians.72 Nationally, 66% of the population is suffering from a noncommunicable disease.73 As of 2015, roughly 5% of the Peruvian population used tobacco and 20% were obese. In America that same year, 20% used tobacco and 37% were obese, yet the mortality rates of diseases related to these co-morbidities were similar.74 This means that noncommunicable diseases are killing people in Peru at a higher rate than elsewhere, likely due to the weaknesses in the healthcare system.

COVID-19

The 2020 global COVID-19 pandemic gives us comparable data of how well countries around the world can handle a communicable disease crisis. Peru is one of only two countries that finds itself in the top 10 in both total cases of and deaths from COVID-19. As of October 2020, 1 in 27 people in Peru had contracted the disease.75 John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center studied the 20 countries most affected by the pandemic and found that Peru ranked number 5 in case to fatality ratio at 3.9%. More astonishingly, as of October 2020, they found that in deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, Peru ranked first at 111; the second ranking country, Iran, was in the low 70s with many of the countries studied not surpassing 50.76 This aligns with historical data in that 20% of the deaths in Peru are attributed to communicable diseases compared to 8% and 10% in Chile and Colombia, respectively.

High Death Rates

The most serious consequence of the lack of access to quality care is death. In Peru, doctors issue a high percentage of the country’s death certificates, yet the quality of data about cause of death is poor, demonstrating a lack of adequate training and understanding of the patient’s conditions. Rural health facilities received higher error scores regarding medical-related death data when compared to urban facilities.77

Although, as mentioned, records are often flawed—the leading causes of death in Peru seem to be mostly treatable diseases and conditions that were either not treated properly or not treated at all. These include many infectious diseases, diarrheal diseases, parasitic diseases, and sexually transmitted diseases.78

Mortality rates among mothers and infants also further demonstrate the insufficient healthcare services in Peru. The data produced by the INEI show that of women in the poorest sectors of Peru who had their most recent birth between 2002 and 2007, 36.1% were attended to in a healthcare facility. This is compared to 98.4% of women in the richest sectors who gave birth in a health facility.79 This disparity in medical attention during childbirth contributes to Peru having one of the highest maternal mortality rates in South America at 68 deaths per 100,000 births,80 and the lack of medical attention in general is linked to the majority of deaths in Peru.

Practices

Improving Healthcare Among Vulnerable Communities

There are many organizations that work to deliver the benefits of quality medical care to those who couldn’t otherwise afford it. Partners in Health is one such organization that fights to make no disease too expensive or too complicated to treat. They work with local governments and smaller sister programs to coordinate and implement health programs focused on the most vulnerable communities. Partners in Health is a worldwide organization, and Peru is one of the countries in which the program currently operates. They partner with The Ministry of Health to find healthcare solutions in Lima urban centers, focusing on maternal and child health, noncommunicable diseases, and tuberculosis. They provide social support, run clinics, and do in-home visits to educate families about and treat these common health issues.

Impact

The Partners in Health organization doesn’t provide any impact data for their programs even though their theory of change states that they collect data to measure their impact.81 They do provide some outputs of their work in Peru; for example, they screened over 70,000 people for TB and had an 83% cure rate of those with positive TB tests.82 Furthermore, they reported that 94% of pregnant women attended more than 6 prenatal visits, though they did not explain who they included in their sample or what qualifies as a prenatal visit. Globally they report 1.6 million outpatient visits in their clinics and 800,000 in-home visits.83 These efforts appear to be part of their nutritional counseling approach, and although they have not reported any reliable impact data, other people who have used similar practices have reported on their success.84, 85 For example, a randomized control trial performed on a program promoting exclusive breastfeeding in Mexico City reported that at 3 months postpartum, 67% of the mothers who received 6 in-home visits and 50% of those who received 3 visits practiced exclusive breastfeeding, with the control group reported at 12%.86

Gaps

There is no aggregated data on the outcome of the practices employed by Partners in Health.87 The organization does not provide enough outcome or impact data to see what the real effects of their intervention are. In order to better demonstrate their impact on the issue, they would need to implement a randomized control trial investigating their in-home visits, social support programs, and clinics. There is also no easily accessible information as to how they qualify local organizations they partner with and help fund, which makes it difficult to determine how well their funds are being used.

Connecting Modern Medicine and Traditional Medicine

As Western medicine has entered Peru, there have been conflicts among indigenous peoples regarding whether they should place their trust in modern medical practices they know little about or rely on familiar traditional practices. This can be challenging as modern medicine often rejects their seemingly effective traditional practices only to replace them with poorly administered Western medicine. The ideal balance between effective traditional practices and newer Western practices is difficult to reach. There are groups that are now attempting to create a better dialogue between Western-trained medical professionals and the traditional medicine workers in rural and Amazonian Peru. They do so by sending diverse teams of experts in both traditional and modern medicine to create permanent intercultural health councils in indigenous villages to promote the proper use of medicine. They train community leaders on the importance of maintaining and promoting traditional treatments to provide the most inclusive and effective treatments for indegenous people. The Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peru (AIDESEP), which means the Inter-Ethnic Association for the Development of the Jungle in Peru, is a leading organization in breaking down the cultural and language barriers that bar so many indigenous people from clinics where modern medicine is practiced and creating these inter-ethnic councils.88 They help traditional medical knowledge be passed down from the older generations to the rising ones and support a community center stocked with medicine and medical equipment.89

Impact

Due to the nature of their work, it has been difficult for AIDESEP to release numerical data of their impact. They do have a list of their main achievements, including developing systems of constant training for their health promoters and the training of indigenous youth as technical nurses in intercultural health, involving signing contracts with higher technological education institutes in Atalaya, Bagua, and Nauta.90 They have also influenced policy makers in the Regional Government of Amazonas in passing Ordinance No. 388, which now requires training in intercultural health and mastery of the local language as hiring criteria for medical professionals and technicians.91 AIDESEP is present in 6 decentralised bodies in the Amazon, encompassing 48 second level federations and territorial organizations that represent 1,340 communities of Indigenous Peoples.92 This influence throughout the Amazon can be considered the output of AIDESEP’s efforts.

Gaps

The obvious gap in AIDESEP’s methods is the lack of reporting tangible outputs, outcomes, and impact. There is little information on how the organization determines which communities to involve in its practices. It may be difficult to judge just how ethical their practices are in intervening with centuries-old indigenous groups and if the help that they can provide them outweighs the potential negative outcomes of getting involved in these isolated communities. The question as to whether it would be ethical to interfere with these indigenous peoples, such as conduct randomized control trials to have more accurate impact data, is one that is highly controversial because of the desire to preserve their culture as much as possible.

Providing Medical Supplies and Equipment

Due to a lack of access to quality equipment and drugs, many people living in resource-poor communities cannot receive proper medical treatment. One practice being implemented is supplying medical professionals in these communities with the resources they need. The purpose of this practice is to help provide communities with materials that they would not otherwise have access to because of socioeconomic or geographic factors. Direct Relief is an international organization carrying out this practice and, specifically, operating in Peru.93 They send packages to such communities and allow the local healthcare professionals to use them as they best see fit. These packages include basic medical supplies such as masks and syringes as well as prescription drugs, vaccines, and personal items.94 They also work to increase the availability of resources for hospitals such as necessary training materials and technological support. Direct Relief has a unique process of using health and crisis mapping powered by advanced analytical tools to track health challenges and related interventions across the globe. This aids them in being accurate and open throughout all of their interventions.95

Impact

Although Direct Relief operates all over the world, they track their outcomes by country. In Peru, they have given over $65 million in medical aid to deliver 885,000 pounds of medical supplies and 34 million doses of medicine distributed between 27 different healthcare providers.96 They also report on many specific successes in improving healthcare through providing supplies in Peru. For example, Direct Relief partnered with a local organization in Peru and was able to provide cervical cancer prevention, screening, and treatment to thousands of women in mountain regions of Peru who could never access it before. This specific intervention involved sending staff, in addition to supplies and equipment, to ensure that necessary training accompanied any products provided.97 Direct Relief reports many positive general outputs such as these through partnerships with various organizations, such as donations of sanitary kits for girls in Peru, shipments of oral antibiotics and eye medicines to treat concerns specific to Peruvians, and other similar aid.98, 99 Further information about the outcomes and impact of these interventions, however, is lacking.

Gaps

Direct Relief’s reports only include outputs, without reporting the outcomes or impact of the organization’s interventions, which makes it difficult to assess the true efficacy of this practice. There may also be adverse consequences to providing medical supplies to healthcare professionals at no charge.100 This could be putting local producers out of business and creating a dependency on their program. Overall, though, Direct Relief seems to be a very efficiently-run organization using analytical programs to guide their relief efforts.

Preferred Citation: Hart, Spencer. “Lack of Access to Quality Healthcare in Peru.” Ballard Brief. February 2021. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints