Linguistic Neglect of Deaf Children in the United States

By Mishonne Marks

Published Spring 2020

Special thanks to Courtney Scott for editing and research contributions

+ Summary

Most deaf children in the United States are born to hearing parents who are not familiar with Deaf culture or American Sign Language (ASL). As a result, deaf children are in danger of experiencing linguistic neglect, meaning they do not receive sufficient language input. This linguistic neglect is typically unintentional and can be a result of deaf history, institutionalized oppression, current stigmas, and educational inequality. Linguistic neglect can result in deaf children experiencing decreased mental health, stunted cognitive development, poor academic performance, and employment difficulties. Several organizations are currently working to address and prevent linguistic neglect by spreading deaf awareness, educating professionals on linguistic neglect, and increasing the prevalence of deaf advocacy groups and support organizations.

+ Key Takeaways

+ Key Terms

Linguistic neglect - A biological state that interferes with the development of neurolinguistic structures in the brain and the necessary developmental processes of early childhood.1

Critical period of language acquisition - A period between birth and age 3 when there is an elevated neurological sensitivity for language development.2

Deaf/deaf - When capitalized, Deaf refers to the Deaf community or culture or to a Deaf individual, if that is the individual’s preference. When not capitalized, it is an adjective used to refer to hearing loss.3 Deaf is a range that includes those with profound deafness (no residual hearing) to those that have enough residual hearing to have a phone conversation. Typically, deaf or hard of hearing people involved in the Deaf community refer to themselves as deaf despite their individual hearing levels.

Functionally deaf - A state of being completely deaf, not able to hear anything, or having profound deafness.

Deaf or Hard of Hearing (DHH) - This term is the one preferred by the Deaf community. The hearing community often uses the term “hearing impaired,” which is believed to be politically incorrect due to its implication that people who are deaf are lacking.

Accessible language - Language that can be clearly understood and acquired.

Linguistic deprivation - A chronic lack of full access to a natural language during the critical period of language acquisition.4

Language input - The exposure learners have to accessible language.5

Language modality - A method of communication. There are many types used with deaf children, the most common of which are auditory-oral, ASL, and sign supported speech.6

Auditory-Oral - This approach is focused on developing competency in spoken language. Spoken and auditory language are the primary, if not sole, modes of communication in this approach.

American Sign Language (ASL) - As a three-dimensional visual language, ASL relies heavily on spatial organization and locations (the three-dimensional space in front of a person) to hold and communicate information.7 ASL is its own manual language, separate from English, with its own grammar and linguistic rules.

Sign Supported Speech (SSS) - A broad category of visual forms of manual English using primarily English syntax and grammar intended to help deaf children learn English.

Institutionalized Oppression - Attitudes taught covertly or overtly in schools, media, homes, and churches that result in the denigration of a minority group’s language, culture, or personhood. Members of the minority group have no power in the institutions that impact their lives and no opportunities for self-determination.

Underemployment - A state of not having enough paid work. This can include situations like working less than full time when one wants to be working full time or doing work that doesn’t fully utilize one’s skills.

Cochlear implant (CI) - A surgically implanted neuroprosthetic device to provide a person with moderate to profound sensorineural hearing loss with a modified sense of sound. A CI bypasses the normal acoustic hearing process to replace it with electric signals which directly stimulate the auditory nerve. A person with a cochlear implant who receives intensive auditory training may learn to interpret those signals as sound and speech.8

Intakes - Reports that are filed then assessed and considered for further action such as legislation towards a policy.9

Context

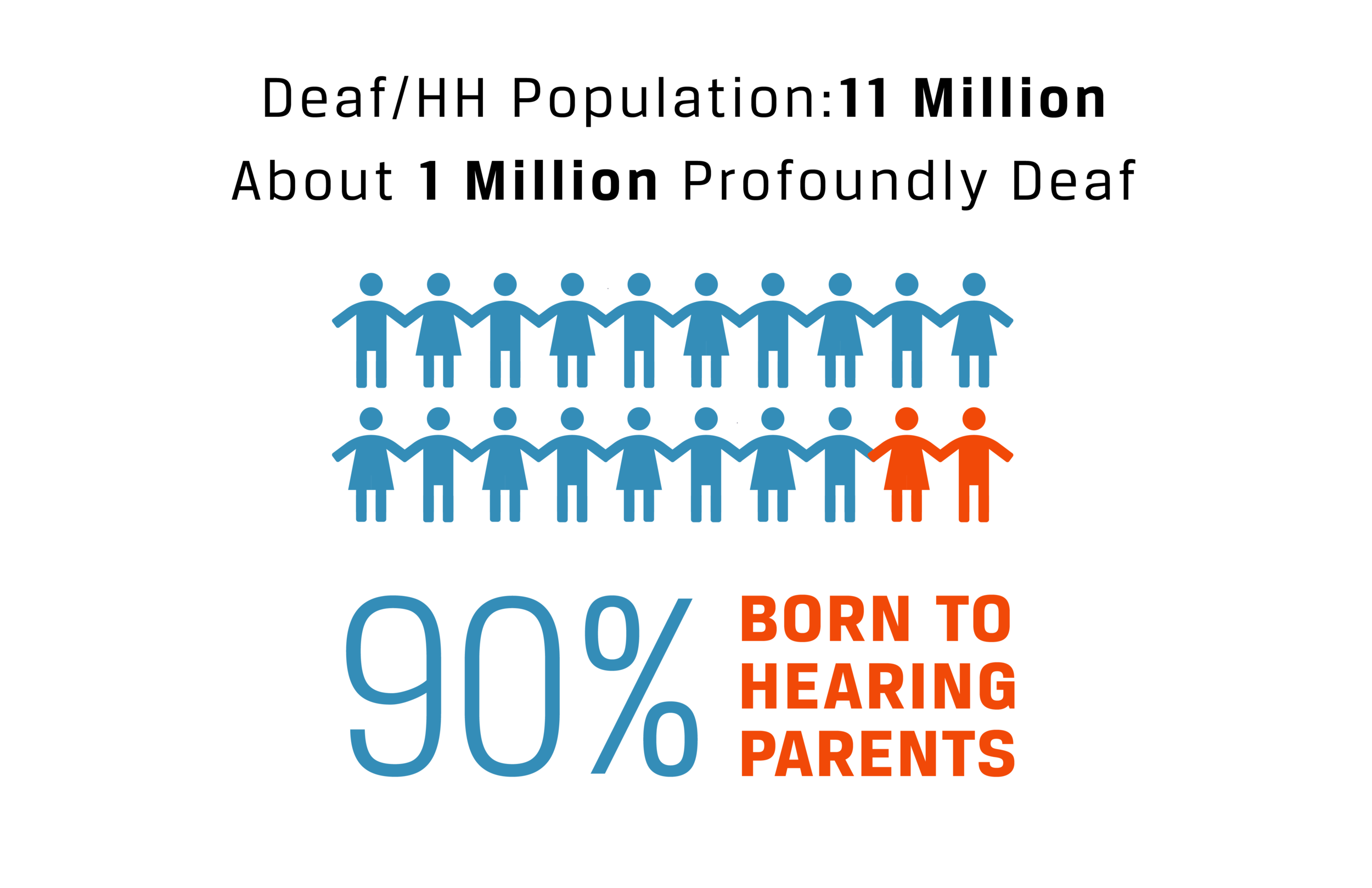

As of 2006, about 11 million people over age 5 in the United States were deaf or hard of hearing (DHH)—roughly 4% of the population. Of those, around 1 million were functionally deaf.10 Out of the nearly 4 million infants born in the United States each year,11 about 2 per 1,000 are born with detectable hearing loss.12 Globally, it is estimated that up to 5 infants per 1,000 born have hearing loss.13 Ninety percent of children born to deaf parents are born hearing, while 90% of deaf children are born to hearing parents.14

Many of these deaf children who are school-aged are sent to hearing schools rather than schools for the deaf; while attending schools specifically for the Deaf used to be a common practice, in 2013 nearly 75% of the 80,000 deaf school children in the United States had been mainstreamed into public hearing schools.15 There are many additional modern practices that minimize Deaf culture and values. For example, an increasing number of deaf children undergo surgeries and are subjected to different physiologically-altering technology that is meant to provide alternative means of hearing. One such practice is the use of cochlear implants (CIs). Roughly 40% of deaf children born between 2012 and 2016 received CIs16—a 25% increase from 2009.17

All children have certain basic physical, emotional, and social needs that must be fulfilled in order to facilitate growth and development. Extra measures must be taken by parents and institutions to provide these basic needs for the many children born deaf each year who do not have the innate capability to learn spoken language. When these needs are not met, the children are considered neglected. A common type of neglect in deaf children is linguistic neglect, which occurs when a child does not receive the adequate language input necessary to promote language development. Some organizations estimate that up to 70% of deaf children experience linguistic neglect.18 All children need regular access to language in their first 3 years of life, which is their critical language development period.19 If linguistic neglect occurs during these critical language acquisition years, it can lead to a chronic form of linguistic neglect called linguistic deprivation>. Linguistic deprivation interferes with the development of neurolinguistic structures in the brain and may stunt a child’s cognitive development,20 perpetuating mental health disorders later in life.21

American Sign Language (ASL) is a significant method of linguistic input for deaf individuals in the United States and thus is important for understanding linguistic neglect. For most of history, ASL was viewed as a set of unorganized gestures that deaf individuals communicated with if they were unable to learn English. It was not declared an official language until 1960, when the linguist William Stokoe confirmed that ASL has linguistic equality with spoken languages.22 23 Historically, language has been equated with speech, but studies prove that language development occurs independent of modality. Further, both manual and oral communications allow people to fully express themselves and should be classified as languages.24 Experts say that learning ASL in the critical period helps prevent linguistic deprivation in deaf children by ensuring a solid language foundation.25 Sign language is an easily accessible language for deaf children because they can learn it naturally if exposed to it regularly.26 ASL overcomes the biological constraints of spoken language to the Deaf community and is a developmentally appropriate way to promote language acquisition for DHH children. Consequently, the decision to withhold sign language from a deaf child can prevent that child from accessing language. It is estimated that only 22% of hearing parents who have deaf children learn sign language themselves, yet there is not sufficient data to report a confirmed percentage.27

As a result of cultural circumstances regarding deafness, there are significant gaps in the literature. Deafness itself is difficult to classify, partially because the US Census does not record the number of deaf individuals but instead groups them under the broad category of disabled.28 Additionally, there is minimal research on linguistic neglect in deaf children since academics only recently began to address it. This makes it difficult to assess the exact number of deaf children who experience linguistic neglect and deprivation. Some of the research that does exist tends to be biased because of the sensitive and highly debated nature of the topic. Much of the information on this topic comes from deaf adults who experienced linguistic deprivation during their own childhood years, creating an abundance of anecdotal evidence of linguistic neglect but a lack of generalizable studies to demonstrate how many deaf children experience linguistic neglect and what their experiences are. Researchers are creating new methods to test for language ability in deaf children, which will eventually allow for an accurate collection of quantifiable data on the topic.29

Contributing Factors

Insufficient Language Input

Linguistic neglect is a direct result of insufficient language input. Deaf children experience natural language development if they receive proper language input, but the way these children receive input is different than the way hearing children do. When deaf children learn reference words for objects, they must be looking directly at the parent or teacher because when they look away they cut off all possible communication. Often, without early childhood deaf intervention, hearing parents are not aware of their child’s visual needs for attention-switching and alternative communication.30 As long as parents are able to effectively work on attention-switching with their deaf infants so they can continue to provide input, the children’s language skills do not fall behind those of hearing children.31 On the other hand, children whose parents are unable to achieve these strategies may experience a lag in their language input.

Attention to visual communication needs seems to be more important than learning sign language alone.32 Extensive gestures combined with spoken language can still foster communication between parents and deaf children. Hearing parents often do not implement these strategies without assistance from early childhood DHH intervention specialists or members of the Deaf community.33 As a result, linguistic neglect is most common in deaf children of hearing families and almost never occurs in hearing children.34 Language skills of deaf children with hearing parents are far behind those of deaf children with deaf parents because of incomplete language models and insufficient parent-child interactions.35 The first competent language model for many deaf children may not be encountered until they begin school, but linguistic neglect often continues throughout and beyond school years.36

Language and culture are inseparably tied, so issues with proper acculturation result in delays in language.37 Most deaf children experience a lack of acculturation to Deaf culture at birth and are not socialized into the Deaf community until enrollment in a residential deaf school or graduation from high school.38 Being distanced from Deaf culture and language leaves the majority of deaf children suffering unnecessarily from linguistic neglect until they become adults.

Deaf History

Linguistic neglect in deaf children in the United States is often a result of the historical interactions between the Deaf and hearing communities that have led to current paradigms about deafness. For years, members of the Deaf community have fought to have their concerns acknowledged because their language was repeatedly stifled through systematic paternalism, which labeled deaf people as a foreign culture to be civilized and assimilated into the majority culture and language.39 Many of the misunderstandings and struggles between deaf and hearing people today stem from a long history of this ignorance and paternalistic mistreatment.

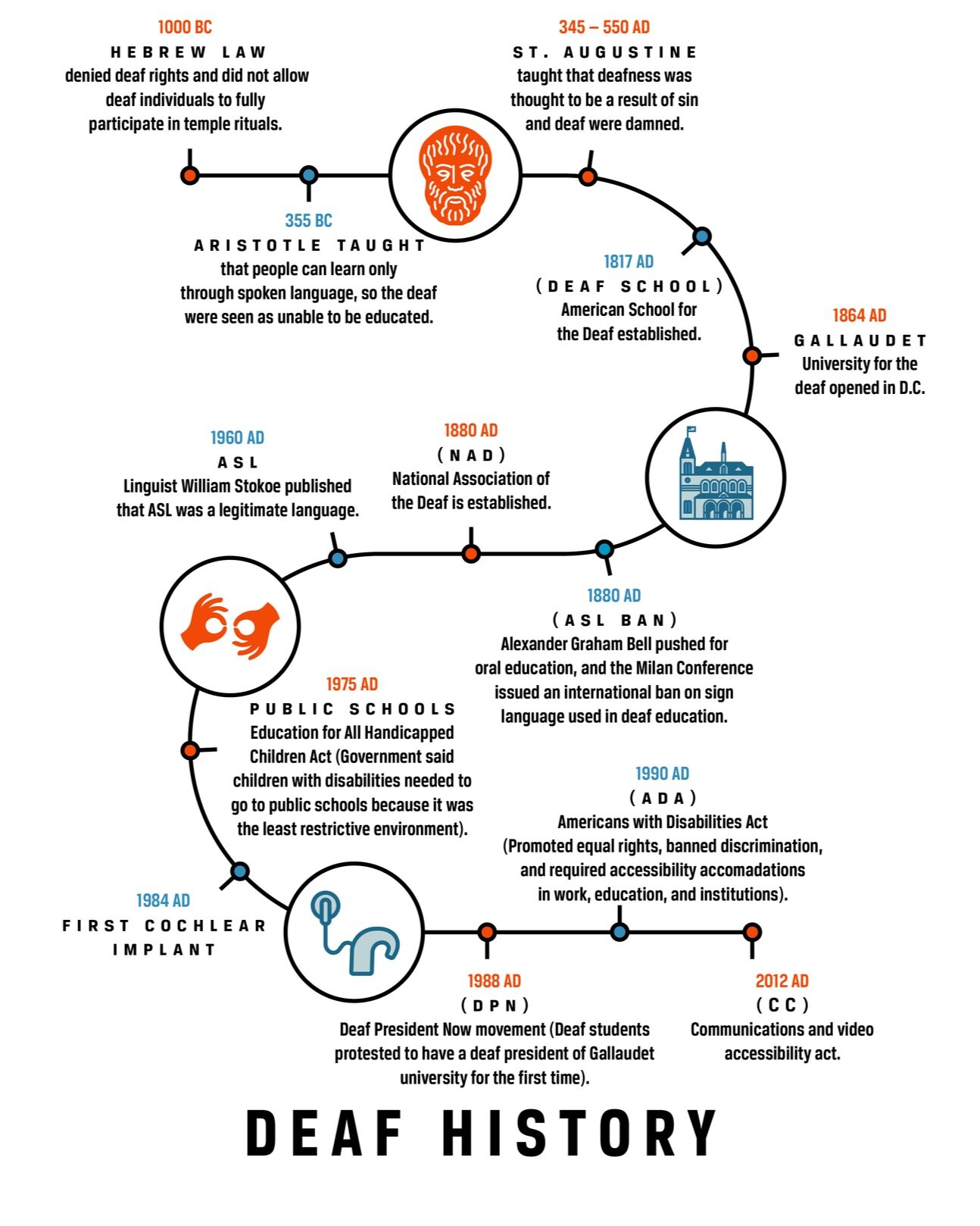

The earliest records of attitudes toward the Deaf community show that hearing individuals had an aversion to deaf individuals. Historically, deafness was seen as a result of sin.40 Those who were deaf were not allowed to participate in religious rituals due to their inability to hear or speak, which led to the assumption that they were damned. For hundreds of years, it was believed that deaf people could not be educated, which perpetuated hearing individuals’ low expectations for deaf individuals.41 During the 19th century, major medical breakthroughs led to the revival of attempts to cure deafness, but these attempts were not always safe, well regulated, or medically sound.42 Around this time, the American School for the Deaf was established in 1817 as the first school for deaf children in the United States.43 Gallaudet University was subsequently established in 1864 to provide those in the Deaf community the opportunity for higher education; this university remains the only completely deaf-focused college in the world.44 Deaf education continued to develop until Alexander Graham Bell, an influential American scientist and inventor, pushed for oral education during the 1880 International Milan Conference.45 The representatives at this conference voted to ban sign language from deaf education because of the belief that all deaf individuals should learn to speak. Of the 164 delegates at this conference, only 1 was deaf.46 This was the catalyst for what the Deaf community now refers to as the Dark Ages of Deaf history.47

The biases against deaf individuals are apparent in the ways they have been treated historically, and the same biases remain prevalent today. Hearing individuals have long been part of a majority population; as the longstanding majority, they have been able to control what occurs in the Deaf community through laws and systems put in place without the input of the Deaf community.48 Throughout history, deaf individuals have fought to have the same rights and quality of life as hearing people. Those rights include being recognized as a minority culture with a complete language, receiving an education, having access to job opportunities, and being able to access information. Today, hearing parents are still devastated when they find out their child is deaf and typically turn to medical professionals for ways to cure their child and help him or her function like a hearing person.49 This often harms the child’s language development and can result in linguistic neglect.

Some major events in Deaf history that relate to the issue of linguistic neglect are outlined below.50

Educational Inequality

Deaf education is a relatively recent practice and, as a result of paternalistic institutions, still hinders adequate education and language development among deaf children. Prior to 1880, many deaf children were instructed by deaf teachers, which gave them a place to develop fluent language, cultural awareness, and understanding of school materials.51 The ban on sign language meant most of the deaf instructors were fired and deaf children no longer had the means to learn sign language in school at a young age.52 These events heavily influenced the current deaf education system. Instead of core subject instruction, hours a day were spent teaching deaf children English through oralism, which was only acquired fluently by a few pupils—and well past the critical language acquisition age. Many deaf students are currently enrolled in oral programs, a rise correlated to the increase in cochlear implants.53

Sign language is slowly resurfacing in some areas of deaf education, yet other, less beneficial, methods of manual language remain in use. One such method is sign supported speech (SSS), which was created by hearing instructors in order to teach deaf students spoken English.54 It employs English structure and grammar mixed with signs from ASL. Methods such as this do not necessarily close the gap between English and ASL. Instead, they have the potential to confuse deaf students, and students may only partially understand what is taught.55 The poor comprehension of these methods perpetuates language learning challenges for deaf students, which can lead to linguistic deficits and neglect in the classroom.

Mediated Education

A shift away from direct education leaves many deaf students with low amounts of information and language input. The majority of deaf students now learn through mediated or interpreted education, meaning students receive instruction secondhand through either a sign language, oral, or cued speech interpreter.56 Mediation also includes instruction received through text, such as transcription of the teacher’s lessons.57 This began in 1975 when the Education for All Handicapped Children Act was passed, stating that all students with disabilities should be taught in the least restrictive environment.58 This caused a majority of deaf children to be transferred out of residential deaf schools, where they experienced direct instruction, to be mainstreamed into public schools, where they were surrounded by almost exclusively hearing peers who learned in spoken English. This made it significantly more difficult for deaf children to learn the information being taught in the classroom.59 Since only 25% of deaf children are currently enrolled in deaf schools, that leaves 75% of deaf children who most likely do not get socialized into Deaf culture or language until after their adolescence.60

Law requires that interpreters be provided to K–12 deaf students that request them. Interpreters make information transfer more accessible, but this process still yields significant deficits. When instruction has to pass through a third party, especially in public school settings, information is lost. One study suggests that deaf students using educational interpreters only comprehend approximately 60%–75% of the content from lectures, as compared to hearing students who comprehend 85%–95% of the content.61 Many factors may influence student comprehension, including the competency of the interpreters. Though developers recommended to state departments that students’ interpreters have at least a 4.0 on the Educational Interpreter Performance Assessment (which measures competency on a 5 point scale), most highly qualified interpreters do not end up working for schools.62 As a result of high demand, many underqualified school interpreters are hired; a 2006 study revealed that only 38% of those working as educational interpreters achieved the minimum proficiency level for most states.63 Even “good” interpreters were reported to incorrectly communicate deaf students’ answers, leaving students feeling embarrassed and frustrated.64 K–12 interpreters are often spread thin and have to fill the roles of friend, teacher, parent, and interpreter.65 Poor education of deaf students and mutual confusion between teachers leaves deaf students with a lingering lack of language communication skills.

Current Stigmas

Many deaf children, especially those born to hearing families, suffer language deprivation as a result of their families’ and societies’ insufficient knowledge of the Deaf world. With Deaf and hearing worlds being separated historically, a spectrum of differing views on deafness have emerged. On the ends of the spectrum exist two models of deafness: the sociocultural model and the audiological model. The sociocultural model, typically supported by members and allies of the Deaf community,66 recognizes sign language as a healthy means of communication for the Deaf community. The audiological model, typically the view of medical institutions and hearing parents,67 views deafness as a medical defect that needs to be fixed or cured.68

When hearing parents grow up with the stigma that deafness is a tragic disability, it often results in high stress for hearing parents of deaf children.69 In contrast, when a deaf child is born to deaf parents, they are often celebrated. In this scenario, there is no grief about the child being disabled or worry about how parents and child will communicate. Deaf parents teach their children sign language and socialize them into the Deaf community with the full belief that their children can be successful in society. Deaf advocates argue that deaf children are not inherently disabled, but they can be disabled by oppression.70 Viewing deafness as a disability may result in grief among hearing parents; if deaf children and their hearing families do not receive adequate support, negative views of deafness accompanied by grief can lead to further issues of linguistic neglect.71

Studies have shown that deaf children develop language most successfully if their parents determine a language mode in the first 6 months of the deaf children’s lives.72 However, many grieving parents do not have time to thoroughly study their options and make a decision about the best language mode for their child early on; instead, during the initial period of shock and grieving, hearing parents are often being referred to many doctors and professionals such as audiologists. During these appointments, the parents receive a large amount of new information to process and may feel pressured to immediately decide what intervention to put in place. As a result of the negative stigma against deafness, parents are asked to make the major decision about what form of communication will most benefit their deaf child at a time when they are feeling overwhelmed and grieving.73 Decisions that delay language input for deaf children are usually made by parents who believe that it is the best option for their child in the long run.

Stigmas Against ASL

Many in the hearing community view ASL as a practice that prevents the growth and integration of deaf children into society—this stigma against ASL deprives deaf children of necessary social and cultural development.74 Professionals often tell parents that, because visual and manual modes of communication come more easily to deaf children, allowing deaf children to learn signs will slow down their development of spoken language. As a result, some parents make great efforts to teach their deaf children spoken English without the use of ASL. Despite this negative view of sign language, evidence reveals that manual language is actually inherent and cognitively beneficial. Further, manual communication and language acquisition come naturally to children.75 76

Full and continual exposure to sign language allows for the same pattern of language development in deaf children as exposure to spoken language does in hearing children.77 Inversely, lack of exposure to sign language may contribute to some deaf children’s inability to fully develop language skills. Deaf children raised orally must go through specialized programs where they are taught to lip read and have hours of speech therapy each day. Some deaf children in oral programs have cochlear implants (CIs) and hearing aids that have varying levels of success.78 Some deaf children are still unable to acquire spoken language after years of oral programs;79 even with cochlear implants, speech fluency is not guaranteed. Implant surgery typically occurs at 12 months of age and the speech processor and access to quality sound do not occur until 14 to 15 months of age.80 Therefore, even if the children do develop sufficient auditory and oral skills after years of daily speech therapy, they miss that initial year of critical language.81 Thirty percent of children with cochlear implants still do not fully develop language without the help of ASL.82 Even for deaf children who do eventually learn to speak, it typically takes over 5 years to reach a proficient level of oral English. Until these children reach proficiency, they are experiencing linguistic neglect. By this time, the child has passed the critical language acquisition window and is at risk of never developing a language fully, which results in linguistic deprivation.

Institutionalized Oppression

The public view on deafness often stems from institutions’ portrayal of hearing as the ideal. When the majority of people view deafness as less-than-ideal, the issue of linguistic neglect is perpetuated because resources and energy are allocated to “curing” deafness rather than to providing children with adequate language input.83 Though some generalized laws in the United States perpetuate this issue, the two main groups at the root of the linguistic neglect issue are Child Welfare Services and medical establishments.84

Child Welfare Services is a government sanctioned program in charge of ensuring the well-being of children in the United States. They protect against the abuse and neglect of children, including inadequate supervision, drug exposure, and physical, emotional, and medical neglect, but they do not include linguistic neglect in their framework.85 Once deaf infants leave the hospital, child welfare workers do not follow up with the child to screen for linguistic neglect.

The influence of medical establishments often comes into play because many hearing parents have never met a deaf person or been exposed in depth to sign language or Deaf culture before they have a deaf child.86 Without personal experiences, parents must rely on the suggestions of professionals, such as audiologists and primary care doctors, to know what is best for their deaf child. Most medical schools and Continuing Medical Education (CME) programs do not teach material involving the biological foundation of language acquisition, the cognitive harm of linguistic deprivation, or the ability of sign language to meet the same cognitive needs as spoken language.87 As a result of historical events, stigmas, and general lack of Deaf awareness, professionals are often not familiar with ASL as a bona fide language nor are they familiar with Deaf culture. Most audiologists and other influential clinicians involved with deaf children adhere to the pathological view of deafness, meaning they view it as a disease that needs to be cured.88 Often, actions are taken to make the deaf child as “normal” as possible, usually trying to employ interventions that will make the child as similar to a hearing child as possible. This typically includes raising the child in oral English, denying the child the opportunity to learn sign language, and ensuring full inclusion in the hearing world (and, therefore, isolation from the Deaf world) by placing the deaf child in a public school.89

Medical institutions are also a primary contributor to linguistic neglect because medical professionals often do not communicate that hearing parents teaching their deaf children ASL is the most reliable safeguard against linguistic neglect, regardless of whether they implement the “ideal” oral methods or not. This may be due to the fact that deaf language acquisition is not something commonly discussed during medical training and class instruction.90 When parents then express concern about the delayed linguistic development of their child, the medical professionals explain that oral methods inevitably yield delayed results because their child is deaf. However, deaf children that learn ASL acquire language at the same rate as hearing children and can even produce signs before they produce words.91 Deafness does not affect a child’s ability to learn a language, just the ability to hear and speak one.92

American law labels deafness as a disability,93 and hearing culture often treats it as a hindrance. Since major institutions such as the government and the US healthcare system are predominantely run by hearing people, this view of deafness as a disability, or a lack of capability, is perpetuated and eventually becomes group discrimination. Even though the Disability Act, which ensures rights such as equal access, has been in effect for over 25 years, many deaf people are still denied rights. Many deaf individuals, for example, report trying to file lawsuits but being turned away because firms would have to employ an interpreter for communication.94 Despite laws protecting against deaf discrimination, a single American law firm has litigated over 100 deaf discrimination cases.95

Consequences

Stunted Cognitive Development

When deaf children experience linguistic neglect, their cognitive development is stunted. Development of neurolinguistic structures in the brain rely on a strong language foundation.96 All children need full access to language in their first 3 to 4 years—the critical period for language development and acquisition—in order to achieve natural language fluency and develop all cognitive structures properly.97 Without natural language acquisition, deaf children are inhibited from forming a strong neurological foundation for developing further social and cognitive skills that are necessary to progress in education and society.

Many deaf children raised with only oral communication do not receive enough auditory information to develop a language. Deaf children who are able to learn sign language naturally from an early age are found to have developed strong cognitive structures, including social communication and sustained attention.98 Some deaf children learn to speak and lip read, but ASL is shown to be the most reliable way to prevent linguistic neglect and ensure language acquisition.99 Without effective language modality within the family, deaf children can feel excluded from family communication and receive minimal social and linguistic input. If parents are unable to communicate with their deaf child, the child cannot develop a sense of identity or interpret social structures.100

Because language and culture are inseparable, fluency in a language is necessary for the child to develop a sense of self and culture. Linguistic neglect prevents the development of empathy and theory of mind, or the ability to interpret and understand other people’s perspectives.101 Empathy and social awareness aid in the development of resilience in dealing with adversity, making it more difficult for deaf children to cope with difficulties.102 Theory of mind deficits mean deaf children suffering from linguistic neglect will not be able to understand that others have their own mental states, therefore making social communication very difficult. Without social communication, children cannot develop cognitive and social skills required for education and a productive life.

Mental Health Issues

Linguistic neglect significantly increases the risk of deaf children suffering from mental health issues. Linguistic neglect prevents deaf children from communicating effectively, or at all, with people around them. Research shows that family communication is crucial to child development103 and that deaf children who have trouble communicating with their family are 4 times more likely to experience mental health problems.104 One of the repeatedly listed risk factors for depression is challenging communication in the home, something that is prevalent in homes with deaf individuals. Deaf adults who reported feeling a lack of inclusion and communication within the home showed evidence of greater depression severity.105 Without effective language modality within the family, deaf children feel left out from family communication and receive minimal social and linguistic input. This social rejection and neglect is correlated with depression and sensitivity to stress.106 Language socialization theory states that people learn language and culture simultaneously, so language delays result in isolation from culture and vice versa.107

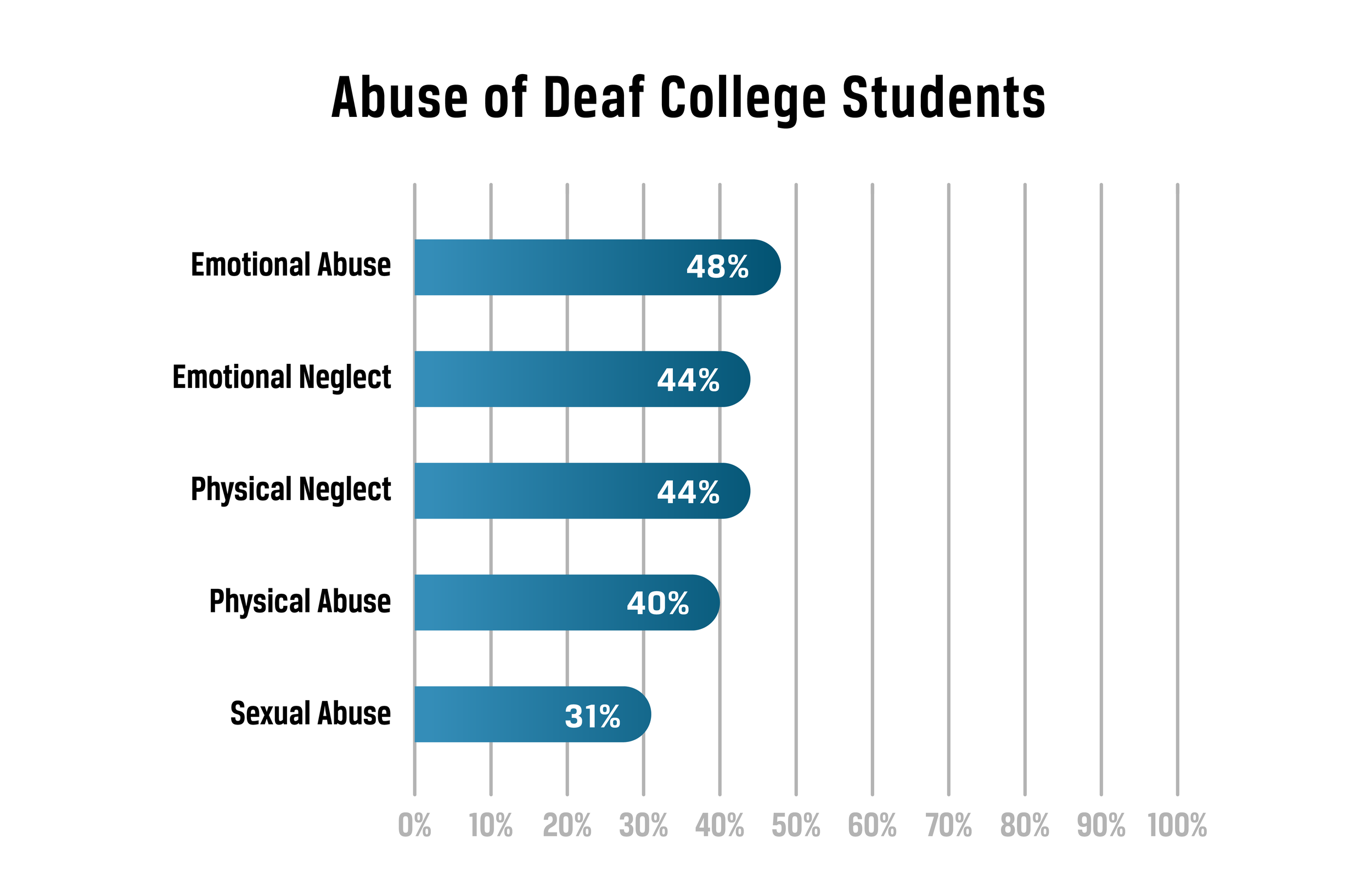

Any form of abuse or neglect will increase mental health risks, and linguistic deprivation specifically further increases the likelihood of other types of neglect occurring. Children with language deficiencies struggle to understand what abuse is and often do not have the tools to report it until later in life. The self-reported numbers of deaf college students who have experienced abuse or neglect before the age of 16 are as follows: 48% report emotional abuse, 44% report emotional neglect, 44% report physical neglect, 40% report physical abuse, and 31% report sexual abuse—with some reporting multiple types of abuse.108 In contrast, only an estimated 12.5% of all children in the United States have experienced maltreatment, such as abuse or neglect.109 Deaf children experience a high rate of neglect, generally, which indicates a high likelihood of linguistic neglect, specifically, and resultant mental health challenges.

Academic Performance

Academic performance is negatively impacted by linguistic neglect. Because access to consistent and frequent communication is necessary for language development, deaf children of hearing parents often begin language learning later than hearing children or deaf children of deaf parents. This is often tied to poor language skills that may inhibit learning in a classroom setting.110 If deaf students enter school with poor language skills, instruction is compromised because attention and time must be devoted to learning language rather than material. These students also struggle with sustained attention, which is crucial to education and adequate academic performance.111 This puts deaf children 1–4 grade levels behind their hearing peers in school and often causes deaf students to fall behind hearing peers on number concepts, language skills, and problem solving skills.112 113

Though all deaf children who lack foundational language can struggle with sustained attention, signing deaf children do better academically than non-signing deaf children.114 Deaf children’s speaking abilities are not correlated with reading achievements; however, trends indicate that higher ASL proficiency is tied with higher English literacy rates.115 English performance is found to improve with even moderate-level ASL skills, and those with the highest ASL abilities achieve significantly higher English scores and literacy skills than those with minimal ASL abilities.116

Another issue occurs when teachers ask deaf children to lip read rather than providing them with proper linguistic input. When deaf students lip read, they can understand 40% of the information at most. When teachers speak while facing a whiteboard or moving around the classroom, or other students speak out of line of sight, deaf students cannot gather information through lip reading.117 These challenges have a negative effect on deaf students’ ability to learn effectively. The average 16 year old deaf student has an 8 year old reading level and is 4 grades behind in math skills, exemplifying the impact linguistic neglect has on ability to learn.118 119

There are significant gaps between graduation rates for hearing and deaf students. Deaf students graduate high school at a 6% lower rate than hearing students. Further, 12% fewer deaf students go on to attend a college or university than hearing students.120 Finally, 18% of deaf college students obtain a bachelor’s degree while 33% of their hearing peers obtain a bachelor’s degree.121 Without the proper academic resources and accommodations, deaf children struggle to progress through collegiate and doctoral education and to become productive in the workforce.

Unemployment and Underemployment

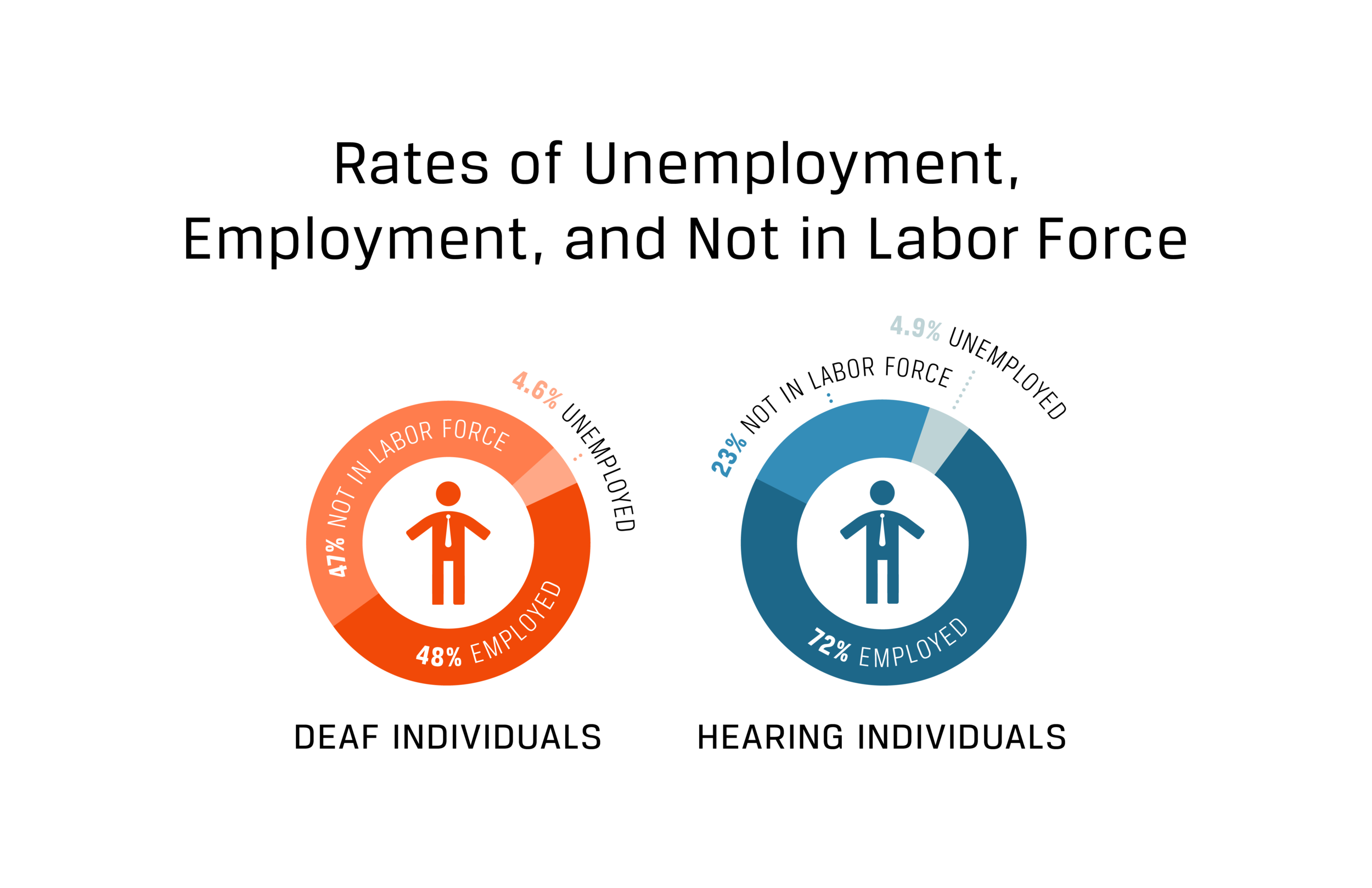

Strong communication skills are a critical part of acquiring and maintaining a job. Therefore, as a result of linguistic neglect and the stigmas surrounding it, underemployment and unemployment are common among the deaf population.122 As a result of language barriers, minimal opportunities, and limited resources, many deaf individuals are not able to reach their maximum employment potential. The average income for deaf individuals is $52,650.123 The total median income in the United States is $61,937.124 The unemployment rate in the United States is 8.8% for people with no disabilities, but 16.1% for disabled persons.125 In 2014, 52% of deaf people were not employed compared to 28% of hearing people.126 Very similar amounts of deaf and hearing people were actively looking for work (4.6% and 4.9% respectively), so the main labor-related difference between these groups was that 47% of the deaf population voluntarily did not participate in the labor force, compared to 23% of the hearing population.127

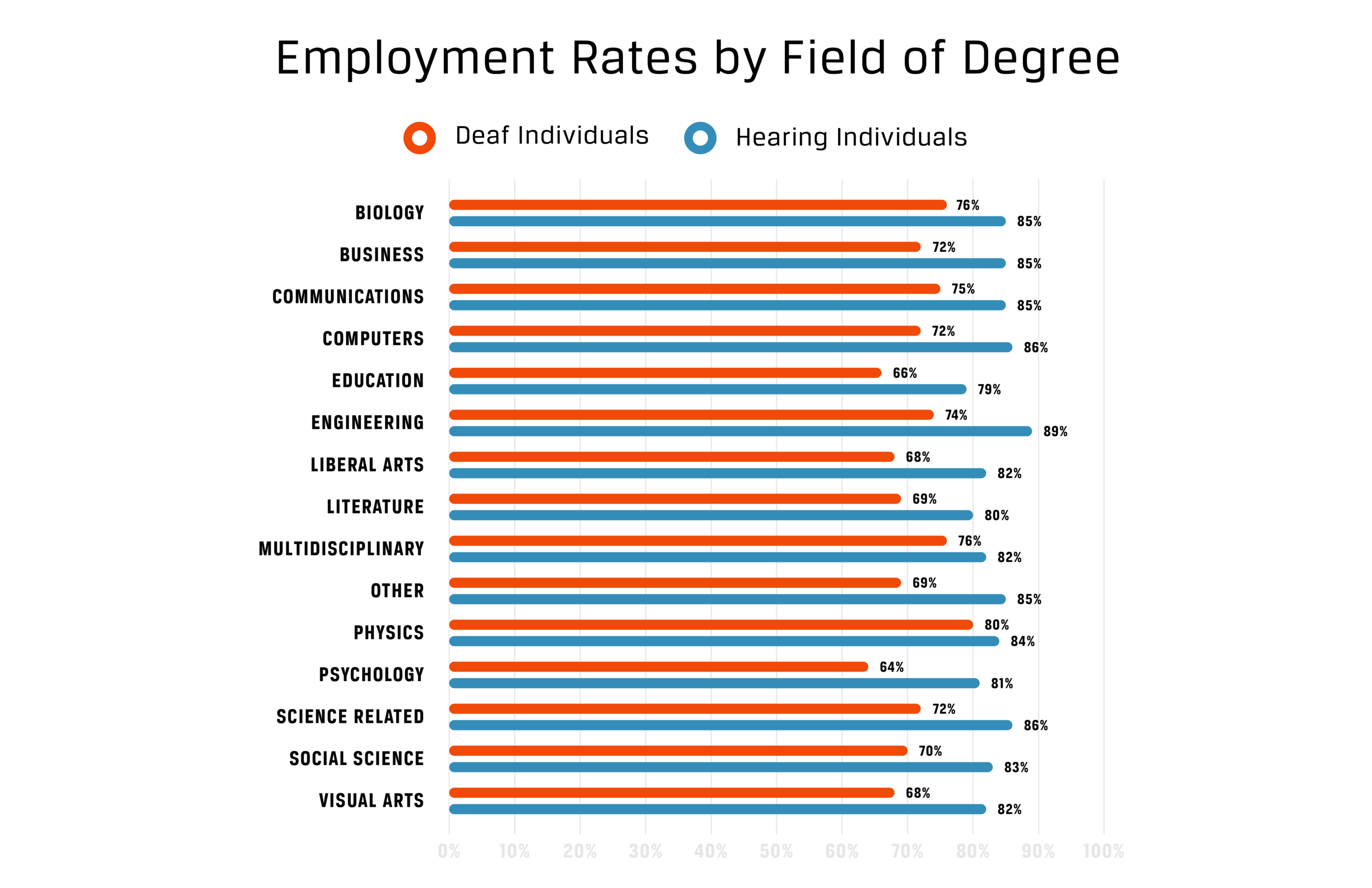

Academic success plays a large role in employment success, but even when accounting for educational attainment, there are more hearing individuals employed than deaf individuals. For example, the same 2014 survey referenced earlier recorded 53.3% of the hearing population with less than a high school diploma as employed, while only 27.8% of deaf individuals with the same level of education were employed. The overall employment rate, regardless of level of education, was 72.1% in the hearing population and 48.3% in the deaf population.128 In every field of study, a higher percentage of hearing graduates are offered a job than their deaf peers.129

As a result of linguistic neglect, which makes job acquisition and retention difficult, deaf individuals are not able to have the same employment opportunities as hearing people.

Practices

Educating Medical Institutions

In order to combat the tendency to accept linguistic neglect as an inevitable side effect of deafness, organizations that educate institutions on deafness seek to help them understand the causes, prevention strategies, and consequences of linguistic neglect in deaf children. Many institutions are not well informed about the Deaf community or ASL. Several organizations have conducted training with medical students and staff to help them be culturally competent about the Deaf world as well as to provide them with information about ASL and its importance in the Deaf community. This helps equip professionals to provide parents of deaf children with a full range of options and give culturally knowledgeable responses and advice to families about how to best help their deaf children.

The Deaf Strong Hospital Program (DSH) focuses on holding a one day training with first year medical students to improve cultural competence. Members of the Deaf/deaf community participate in role plays to help the students learn to address relevant cultural, linguistic, and communication needs of deaf patients. DSH aims to improve the quality of health care for deaf people.130 DSH was started in 2000 after a study found that deaf individuals had fewer physician visits and were less likely to see a physician than majority groups due to difficulty communicating feelings of fear, mistrust, and frustration.

The Deaf Community Training (DCT) program teamed with Medical Student and Cancer Control with the intent of training physicians about Deaf culture to improve the way they care for deaf patients.131 This was a 2-year program that sought to eliminate cultural stigmas surrounding deafness and linguistic barriers between physicians and patients. Part of achieving these aims involved teaching physicians ASL; when physicians can sign, deaf patients are more likely to follow health recommendations and visit physicians regularly.132 The DCT program involved performing research projects about the Deaf community, taking 6 quarters of ASL classes, and completing a summer immersion program at Gallaudet University.133

Impact

DSH tracked the effects of the program through a satisfaction survey of its participants. Of participants that completed the program since 2006, 90% reported that they agree or strongly agree that participation in the program helped them realize the importance of cultural, linguistic, and communication issues in healthcare with deaf patients. In 2012, past participants who had moved on to the clinical portion of their training were contacted and 97% said that the program was a valuable experience. Some of these past participants also reported that they apply lessons they learned from DSH in their clinical practices now.134

DCT gave a survey assessing knowledge of Deaf culture to students who had completed the DCT program, students who had not, and current faculty teaching these students. Out of the 28 questions in the test, DCT students scored a mean of 26.90, faculty scored a mean of 17.07, and non-DCT students scored a mean of 13.79. This demonstrates that students had gained cultural competence from the DCT program that would aid them in treating deaf patients. They were more able to give medical advice with cultural sensitivity and to respect the linguistic importance of manual language.135

Gaps

The statistics reported by these organizations demonstrate the effectiveness of the program in improving the cultural competency of physicians, but no data was reported to determine the effect over time on overall medical treatment for deaf individuals. Additionally, there is no evidence that cultural competency training has helped mitigate the effects of linguistic neglect. The DSH program is praised for its effective implementation at the University of Rochester, yet it is only accessible for medical students who are enrolled in this specific university.136 Furthermore, these programs target medical students only, while there are still gaps in cultural competency among many current medical professionals. The impact of programs like this may be magnified by integrating them into continuous education programs in hospitals throughout the United States.137

Early Intervention Programs

In the United States, hearing loss is the most common congenital condition; about 3 out of every 1,000 infants are born with moderate to profound hearing loss. Since child development relies so heavily on language, DHH infants are considered to be in danger of a potential developmental emergency. Their condition needs to be identified as soon after birth as possible. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) mandated Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EDHI) programs in each state in order to try to prevent developmental delays. These programs were put in place because, in the past, it often took months or years for hearing parents to learn that their child was deaf. There are many different programs branching from the federal mandate under the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). The goals of the AAP EHDI program are to ensure every child with hearing loss is diagnosed and receives intervention in a timely manner, enhance pediatricians’ and other physicians’ and clinicians’ knowledge of the EDHI guidelines, ensure each state’s newborn hearing screening regulations are communicated to parents, and incorporate EDHI into a medical home approach for child health.138

After proper screening, the next step is intervention. Linguistic neglect often occurs in deaf children born to hearing parents who are then not acculturated into the Deaf world. Intervention allows a trained professional to show strategies of effective communication and language development between the parent and child.

Impact

EDHI’s purpose is to detect infant hearing loss early and start intervention right away. There are laws in all 50 states providing screening and necessary intervention.139 The enactment of the EDHI program has shown a large increase in the number of DHH infants detected early on. In 2017, 65.1% of the 6,537 children with detected hearing loss were enrolled in early childhood intervention programs.140 In 2000, only 855 infants were identified as DHH, but as of 2016 the number has increased to over 6,000 infants a year.141

Gaps

Though the EDHI greatly improved the efficiency of hearing loss screening in infants, no additional tracking or data collection occurred after enrollment in an intervention course. General statistics show that intervention within the first 6 months is crucial, but because of gaps in data collection, there is no specific information on how linguistic neglect has been affected by EDHI.142 It is difficult to identify with the lack of data, but further research may prove this practice to be extremely effective in addressing linguistic neglect, as it modifies behaviors and provides immediate intervention.

Promoting Deaf Rights

Many policies and institutions have stifled the use of sign language and perpetuated linguistic neglect. The purpose of deaf rights organizations is to fight against unfair laws and opportunities that put deaf individuals, including children, at a disadvantage. This includes advocating for state and federal laws and policies to protect human rights for deaf individuals. As mentioned previously, paternalistic problems arise because most governmental organizations, like the National Board for Education, are run by hearing people. When laws are passed that affect the deaf population, there is not a fair representation of deaf individuals to weigh in on the decision. These organizations seek to facilitate a strong movement of Deaf pride—a movement that rejects the idea that deafness is a disability and promotes the belief that deaf individuals are complete, functioning humans.

The National Association of the Deaf (NAD) is the largest civil rights organization created by and for the Deaf community in the United States. Their purpose is to ensure civil, human, linguistic, and cultural rights for the deaf population. One of their main focuses is preserving, protecting, and promoting ASL so that deaf individuals do not experience linguistic neglect. The NAD carries out federal advocacy work to improve deaf lives in areas such as early intervention, education, and employment.143 They hold conferences and advocate for public policy that will maintain deaf individuals’ rights. Deaf organizations like the NAD involve deaf individuals in legislative and policy work. This allows experienced deaf people to work to make sign language and deaf education more readily accessible and accepted.

Impact

The 2017–2018 Annual Report for NAD shows the diverse outputs of the organization. In total, the organization has worked on 5 federal bills: the EHDI, the IDEA Amendment Bill, the Signing is Language Bill, the LEAD-K bill, and the Deaf Children Bill of Rights. They ran several major initiatives including the Gift of Language Campaign, the Parent Advocacy App, and the National Deaf Education Conference with 151 attendees and international presenters from 10 countries. The NAD ran 6 state-level trainings on education advocacy and had 198 education advocacy intakes. In preparing for legislation, they accumulated 44 training hours. The Law and Advocacy center had 1372 intakes. Out of the 275 policy intakes, 39 resulted in policy filings—the majority of which were with the Federal Communications Commission.144

The organization redesigned the Described and Captioned Media Program website (dcmp.org), which allows deaf people to consume online material. The program added 911 new items, gained 9,053 new members, and had 6.2 million views of their webpage. The NAD was able to promote the development of deaf youth through the Youth Leadership camp of 63 campers and the 26th Biennial Junior NAD Conference of 82 delegates, 38 advisors, and 23 chapters.145

Gaps

Much of the NAD's work is in political advocacy, making it difficult to report solid outcomes or impact. Furthermore, it is difficult to see exactly how linguistic neglect has been affected. The NAD’s goal is long term change of deaf rights, which will trickle down to each individual. With much of this advocacy happening currently, before and after comparisons will not be able to be reported on until the bills have been implemented and had time to take effect.

Preferred Citation: Marks, Mishonne. “Linguistic Neglect of Deaf Children in the United States.” Ballard Brief. June 2020. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints