Migrant Smuggling Across the Mediterranean Sea

By Lorin Utsch

Published Spring 2021

Special thanks to Hannah Pitt for editing and research contributions

Summary+

Many migrants are making the dangerous crossing of the Mediterranean Sea through the use of migrant smugglers. Though illegal, migrants choose to make this journey due to a combination of push and pull factors, including instability in their homeland and a lack of legal options of emmigration. The smugglers are highly motivated by profit and take advantage of the migrants’ needs, leading to instances of monetary exploitation, sexual abuse, and human trafficking. As a result of the smugglers’ motivation for profit, the lives of the migrants are often placed in hazardous situations, often resulting in death. Because of the illicit nature of migrant smuggling, there is a lack of regulations set in place to protect the migrants on their sea crossings and a lack of infrastructure to meet them once ashore. The current practices in place to alleviate this social issue include search and rescue missions aimed at mitigating short-term dangers for the migrants and international treaties aimed at protecting their rights long-term. The most impact will be made by individual states adopting increased criminalization measures against migrant smugglers and increasing resettlement quotas for the migrants searching for a new home.

Key Takaways+

Key Terms+

Unaccompanied minor—Person who is under the age of 18, unless, under the law applicable to the child, majority is, attained earlier and who is “separated from both parents and is not being cared for by an adult who by law or custom has responsibility to do so.

Refugee—Someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war or violence. A refugee has a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.1

Asylum seeker—Someone whose request for sanctuary has yet to be processed.2

Human smuggling—The procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial gain or other material benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or a permanent resident.3

Irregular migrant—“Movement of persons that takes place outside the laws, regulations, or international agreements governing the entry into or exit from the State of origin, transit or destination.”4

Durable solution—“Any means by which the situation of refugees can be satisfactorily and permanently resolved to enable them to live normal lives.”5

Repatriation—“The act or process of restoring or returning someone or something to the country of origin, allegiance, or citizenship.”6

Local integration—“The settlement of refugees with full legal rights in the country to which they have fled.”7

Resettlement—“The transfer of refugees from an asylum country to another State, that has agreed to admit them and ultimately grant them permanent residence.”8

Arab Spring—“A series of anti-government uprisings affecting Arab countries of North Africa and the Middle East beginning in 2010.”9

European Union (EU)—“International organization comprising 27 European countries and governing common economic, social, and security policies.”10

Search and Rescue Missions (SAR)—“An operation mounted by emergency services, often well-trained volunteers, to find someone believed to be in distress, lost, sick or injured” at sea.11

Context

Q: How many migrants are crossing via the Mediterranean Sea?

A: Since the 1970s, there have been over 2.5 million undocumented migrants who have crossed the Mediterranean Sea.12 The number of migrants taking this trans-Mediterranean route peaked in 2015, with the UN reporting that 1 million migrants had made the journey that year.13 Although the flow of refugees across the Mediterranean has dropped significantly compared to 2015, the number still remains high; in 2018, 139,300 people crossed the Mediterranean14 and in 2019 the number was 110,699.15 As of September 21, 2020, 50,170 people have arrived in Europe via the Mediterranean Sea,16 and the United Nations has reported that the COVID-19 Pandemic will likely not decrease the annual average numbers of migrants smuggled across.17

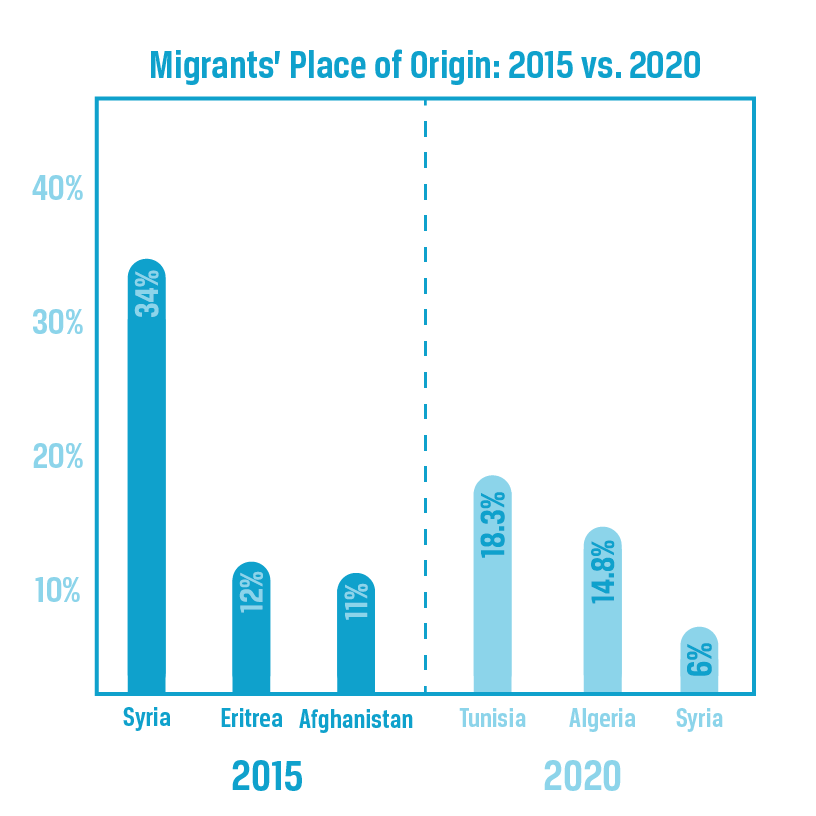

Q: What countries are migrants coming from?

A: At the peak in 2015, the people who were coming across the Mediterranean were mostly from Syria (34%), Eritrea (12%), and Afghanistan (11%).18 Syria remained the top country of origin for the next few years, but recent data has shown a shift in demographics. As of September 2020, Syrians make up 6% of the migrants.19 Tunisia is the top country of origin for recent migrants with 18.3% and Algeria is second highest with 14.8%.20

Q: Who is making these crossings?

A: While there is not specific data on the Mediterranean arrivals in particular, of all the people who have applied for asylum in Europe, most are young males, often unaccompanied minors.21 Of all the asylum applications in 2019, 207,000 of them were under 18, 7% of which were unaccompanied minors.22 While many women and children make this journey, it is often men who cross the Mediterranean Sea in order to find work and eventually reunite their whole family in Europe.23

Q: Are these people considered refugees or are they economic migrants?

A: A refugee is defined by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees as someone who has fled their country and has a “well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.”24 While many people might be able to claim refugee status, before their case is legally accepted they are deemed asylum seekers—“someone whose request for sanctuary has yet to be processed.”25 While it is impossible to know if all the asylum seekers crossing the Mediterranean fit the credentials to obtain refugee status, the risk that each of them has decided to take in attempting the journey alludes to the situations they are fleeing from.

Economic migrants, on the other hand, are crossing not due to push factors such as violence in their country of origin but rather due to pull factors such as job opportunities in European countries. There is a lack of data in regards to just how many trans-Mediterranean migrants fit this description, but it is estimated that this group includes lower than 33%, the other 67% being classified as either “likely refugees” or “undetermined status.” 26 While the distinction between economic migrants and refugees may be a topic of controversy, economic migrants are still facing the same hazardous conditions as refugees are and are knowingly putting themselves in danger in order to secure a future that is better than the one they are leaving behind. Philippe Fargues, published alongside the International Organization for Migration, explained this dilemma: “There is no doubt that any person making the decision to cross the Mediterranean at the risk of his or her life has imperative reasons to do so. Looking at the mix of despair and hope that motivates the move, the distinction between voluntary and forced migration—the first referring to economic causes and the second to political causes—is helpless.”27 Once apprehended on land, economic migrants who do not fit the requirements of refugee status will be sent back to their country of origin. However, they must survive the Mediterranean crossing in order to even get to this point. Because of this, the term “migrant” will be used throughout this brief to refer to economic migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees.

Q: Where are these migrants going?

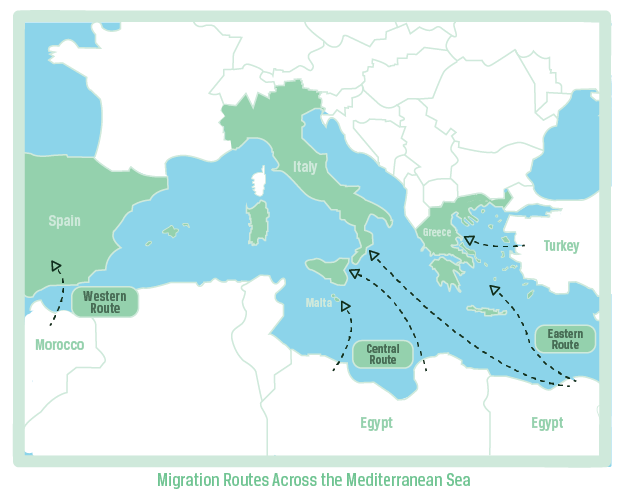

A: There are various routes that can be taken to cross the Mediterranean: the Western route, the Central route, and the Eastern route. Migrants taking the Western Route come from West Africa, Syria, or Morocco and land in Spain.28 The Central route sees migrants smuggled mostly from the Horn of Africa to the coast of Italy, specifically Sicily.29 The Eastern route is used by Afghans, Syrians, Iraqis, and other migrants from Southwest Asia, with Greece being their arrival goal.30

Europe is the frequent destination for migrants in this region due to its close proximity to regions of conflict and due to its stable economy. Data is not available as to the specific reasons migrants crossing the Mediterranean decide to land in Europe, but information gathered from all new residents of the EU cited family, work, asylum, and education as their top reasons for emmigration.31 These pull factors contrast against many of the hardships migrants are facing in their own countries, and the Mediterranean Sea is the most accessible route to both flee persecution and obtain relief in Europe.

Q: How are they crossing?

A: It is estimated that 90% of migrants travel to Europe through the use of a criminal network.32 Migrants likely come to Europe this way since the legal avenues available to them are rigorous and rarely result in resettlement, with only 38% of asylum decisions ending in positive results.33,34 Most, if not all, migrants are being transported on boats manned by smugglers.35 Suspects in this multinational trade of smuggling originate from over 100 countries.36 The boats that carry the refugees are severely overcrowded and not fit for trans-Mediterranean travel.37 The boats used by smugglers are often meant to get the migrants close enough for rescue patrols of the coastal countries to hear their signal and take them to shore. After this, the smugglers abandon the boats.38

Q: What are the legal implications of these crossings?

A: Under international law, migrant smuggling of any kind is illegal.39,40 However, the Model Law against the Smuggling of Migrants emphasizes the differences in rights and repercussions between the smugglers and the migrants being smuggled.41 The principle of non-refoulement42,43 and the United Nations Convention on the Laws of the Sea protect all migrants apprehended in search and rescue missions on the Mediterranean Sea.44 Since there is no way to distinguish between an economic migrant, asylum seeker, or refugee until they undergo the correct legal processes on land, all migrants must be rescued off the sea. While some migrants will face rejected asylum applications and deportation once ashore, the immediate need to bring them to safety must be acknowledged under international maritime and human rights law.45,46

Smugglers are aware of this fact and thus aim to bring the migrants’ boats close enough to territorial waters for rescue parties to reach them. The country responsible for the search and rescue mission depends on the location of the boat in the Mediterranean.47 Though the country is legally bound to provide relief at sea, the country intercepting the boat will be able to decide whether or not to allow the boat to dock on land.48 Boats full of migrants have been denied coming ashore in the past, but the country can then be liable if the boat was found to be in need of urgent humanitarian aid.49 As more migrants are successfully brought to shore, more issues emerge for the coastal countries, with Greece and Italy being particularly overwhelmed. In 2019, Italy would not allow boats to dock on their shore until the load of migrants was distributed to other countries in the EU.50 When migrants are stuck between multiple parties, the migrants are in particularly vulnerable positions, with no group or country wanting to take responsibility for their wellbeing. Because smuggling is an illicit activity, there is no way for the receiving coastal countries to be completely ready to anticipate the migrants’ arrivals or fully supply their needs once ashore, contrasting to migrants who come through legal channels of resettlement.51 If migrant smuggling is not controlled, its effects on the migrants and the receiving countries will also go unchecked.

Contributing Factors

Unstable Situations in Homeland

Excluding economic migrants, asylum seekers are making the journey across the Mediterannean due to conflict and human rights abuses in their countries of origin.52 For instance, of the migrants arriving to the prominent destination of Greece, 85% were from countries experiencing political turmoil, including Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Iraq.53

Syria has been experiencing internal conflict ever since protests against President Assad’s regime escalated into a civil war in 2011.54 With peace talks stalled and casualties reaching over 400,000, many Syrians have sought to flee the conflict.55 As of October 2020, 5.6 million have left Syria and gained refugee status elsewhere.56 While most Syrian refugees are in neighboring countries such as Turkey or Lebanon,57 Europe has resettled about 1 million,58 granting protection to over 96,000 Syrians in 2018.59 While Syria is no longer the highest contributor of refugees crossing the Mediteranean, the country continues to face violence and security threats.60

Tunisia, the current top country of origin for those crossing the Mediterranean, has also been experiencing civil unrest.61 The tensions that peaked in 2011 and resulted in protests, government instability, and violence known as the Arab Spring are still being felt by marginalized groups in many of the interior regions.62 The 200 political movements that came along with Tunisia’s elections in 2019 are evidence of the citizens’ continued dissatisfaction with their current state of government and social imbalances.63,64,65 Tunisia’s financial system has not recovered from the 2011 revolution, and the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these effects, causing their government to default on loans from 4 other nations.66 Emmigration of the unemployed is thought to be one of the only things standing in the way of another social implosion.67

Many migrants did not choose Europe as their first destination after fleeing their country of origin but had instead chosen to embark there after spending years in neighboring countries deciding how to reestablish their lives.68 Many migrants fleeing conflict in Africa had planned to stop their journey in Libya, but civil war and attacks on civilian infrastructure has left 60,000 refugees vulnerable to continued violence.69 Other countries of origin include Afghanistan, Eritrea, and Somalia, all of which have seen a rise in violence and human rights violation since 2014.70 Because of these threats, many are choosing to continue onward towards Europe, embarking across the Mediterannean.71 As one teenager from Gambia described it, “We knew it was dangerous, I knew it was dangerous, but when you have a lion at your back and the sea in front, you take the sea.”72

Smuggling Market

High Profits for Smugglers

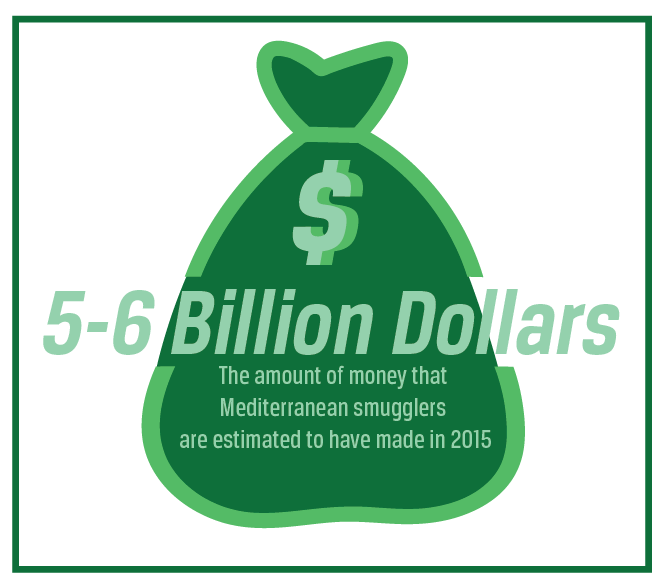

Smugglers obtain high monetary compensation for coordinating Mediterranean crossings. It is estimated that in 2015, smugglers made $5-6 billion,73 and some estimates even project this number to be as high as $35 billion.74,75 Smugglers can gain high profits from relatively few journeys, as one trip from Tunisia to Sicily can earn smugglers €50,000 ($60,712).76 This revenue comes from ticket sales that can be inflated based on demand or risk to the smuggler.77 In 2018, migrants paid €1,800 ($2,185) to cross through the Central Mediterranean Sea.78 In order to ensure safer travel, some migrants have paid up to €100,000 ($121,425) to get from the Middle East to Europe.79 In order to cross the Mediterranean and reach Europe, migrants must often go through many different legs of the trip, and they pay for each one separately.80 Many smugglers, specifically in the Horn of Africa, demand payment before the initial boat crossing, which means the smugglers are guaranteed a profit regardless of whether or not the migrants arrive safely to their destination.81 Increased ticket prices allow for a more sophisticated method of smuggling and is projected to lead to other criminal activities amongst the smuggling rings.82

Lack of Legal Repercussions

While these smugglers are making a profit, they are simultaneously escaping legal repercussions due to the lack of legal coordination between the countries involved.83 While laws exist to hold smugglers accountable, the implementation of such consequences proves difficult to accomplish.84 The network of smuggling around the Mediterranean is made up of multiple smaller rings, and the more centric smugglers possess even more autonomy within the smuggling market.85,86 Between 2002 and 2018, over 3,200 smuggling networks had been found in Morocco alone.87 The multi-layered and competitive nature of the market makes it difficult for authorities to halt their criminal journeys.88 Smuggling by sea allows the smugglers to easily alter their routes in response to any new policing initiatives.89 By using social media such as Facebook or WhatsApp to connect with the migrants, smugglers obtain even more flexibility and are able to market their services through inexpensive and effective means.90,91 In order to correctly apprehend and prosecute these smugglers, the countries involved would have to coordinate their efforts. This coordination is made difficult due to the delineated territories in the Mediterrean and due to the tensions over “disputed” water, particularly between Greece and Italy.92 These two countries are also the top destinations for incoming migrant boats, making the need for their coordinated response even more imperative.

Lack of Alternate Migratory Options

Closure of Land Routes for Migrants

Migrants resort to crossing the Mediterranean when other means of entering Europe are closed. The sea routes provide alternate options for when the land routes are no longer able to be used. As more migrants enter Europe illegally, many countries have responded by closing their borders.93,94 Border closures in Macedonia, Croatia, Slovenia, and Turkey have left migrants with few options for overland travel.95 Over 72,000 migrants (22,500 of which were children) became stranded in Greece, Cyprus, and the Balkans following border closures.96 Hungary, a common entrypoint to Europe for asylum seekers,97 has legalized detaining migrants in detention centers along the country’s border, which dissuades migrants from entering Europe through that route.98

It is important to mention that border closures between European countries remain an issue even after migrants arrive via the Mediterranean Sea. In reaction to the influx of irregular migrants in 2015, many European countries have adopted restrictive border policies that tend to favor domestic security in detriment to migrant mobility.99 Facing the threat of deportation or border closures, migrants are likely to turn to other routes to enter Europe. This propensity for more clandestine and open routes is reflected in the fact that only about 10% of undocumented migrants entered Europe over land in 2020.100

Lowering of Refugee Quotas Worldwide

The low number of migrants who are legally resettled paired with the increased need for resettlement has led to an increase in illegal migration processes across the Mediterranean Sea. Migrants must look to resettlement as their only other long-term solution when repatriation to their home country is not possible due to unsafe circumstances and when local integration is not available in unstable host countries.101 However, less than 1% of refugees who apply are resettled every year,102,103 and the quotas for primary destination countries have fallen to a historical low.

The United States, historically the country to resettle the most refugees per year, has continued to drop its admissions from 85,000 in 2016 to 15,000 in 2021.104,105 Similarly, Canada’s quota for refugee admissions decreased from 46,700 in 2016 to a planned 30,000 in 2020, although there are not easily accessible reports on whether Canada met that cap or not.106 The UNHCR has reported yearly decreases in refugee resettlement departures, from 126,291 in 2016 to 17,628 in 2020.107 With only 4.5% of resettlement needs being met in 2019, and as the need for resettlement increases to 1.44 million for 2021, migrants face low odds of resettling legally.108

Migrants who are trying to obtain resettlement in Europe must undergo a lengthy legal process. Even once migrants’ cases are accepted for resettlement, they may have to wait up to a year to be resettled in a third-party country, leaving them vulnerable to continued persecution in their original situation.109 In 2020, the European Union pledged to resettle 30,000 refugees legally,110 but the need for increased quotas is evident in the additional 94,000 migrants arriving illegally via the Mediterranean Sea.111 Legal resettlement is often not a viable or realistic option for migrants escaping hazardous situations, which means they must turn to illegal means of finding refuge through the use of smugglers.

Consequences

Death and Physical Harm

The smuggling routes across the Mediterranean Sea are infamous for their hazardous conditions, which frequently lead to death and other physical harm.112 Since 2014, over 19,000 migrants have died crossing the Mediterranean Sea.113 However, this number can be prone to large margins of error since almost 12,000 of the 19,000 bodies were never found.114 It is likely that even more bodies were not accounted for and that many missing persons are believed to be dead. While the total number of attempted crossings has gone down since the peak in 2015, these lower numbers of attempts are pointed to as evidence of the increased deadliness of the journey.115A cutback on sea patrols and rescue operations starting in 2018 have exacerbated the danger that being smuggled across the Mediterranean already entails.116 In 2020, 10 migrants would die or go missing each week as they tried to cross the sea.117

While these dangers of drowning are felt by all migrants who take this route, migrants who travel using the help of smugglers often face a higher likelihood of danger. The water in the Mediterranean is known for being rough and choppy, and this hazard is exacerbated when traversed in precarious boats.118 Due to the smugglers’ economic motivations to cut costs, the boats used by smugglers can be rickety, wooden fishing boats that are manned by a crew member who masquerades as a migrant to rescue parties, or the boat could be a rubber dinghy boat, with no crew member onboard.119 These dinghies are meant to hold around 20 people, but there have been reports of officials rescuing these rafts with more than 100 people onboard.120 The wooden boats also pose a threat of capsizing, as they are often overcrowded and easy to tip. In 2015, one of these boats sank due to the 900 people onboard all moving to one side as they tried to reach another boat that had come to bring them to shore.121,122

Smugglers also strive to increase their profit margin by investing in fake life jackets rather than ones with life-saving abilities. These fake life jackets are so widespread along the migration route that the World Health Organization places these fake life jackets as a common health hazard that migrants can face.123 Migrants place trust in the life jackets given to them by the smugglers, but since smuggling is already an unsanctioned behavior, smugglers rarely follow the same safety guidelines that are required of registered boats.124 These life jackets have been reported to be filled with bubble wrap, dense foam, and compressed paper and some migrants have jumped overboard only to stumble ashore under the weight of their fake life jackets, while others drown having put faith in its life-saving capabilities .125

Most deaths occur due to drowning at sea (80%), but many migrants die following their arrival to shore.126 When migrants arrive via smuggling, they are doing so illegally which then tinges their land arrival with hostility and legal challenges that they must face before obtaining true safety. Since most migrants are rescued by countries’ and organizations’ official search and rescue missions, the migrants may find it difficult to remain hidden or escape scrutiny under the legal system.127 Since 1993, over 500 migrants have died in Europe following their experiences with the asylum process, detention centers, refugee camps, and prisons, with suicide being the leading cause of death.128 After illegally arriving in Europe, over 750 more migrants died following their subsequent deportation.129 If migrants were to obtain legal resettlement status rather than having to resort to migrant smuggling, these hardships that face them ashore would be largely bypassed.

See comprehensive list of individual migrant casualties in the Mediterranean Sea in PDF below.

Exploitation

Migrant smugglers often exploit migrants in their journeys crossing the Mediterranean. This exploitation includes extortion for monetary purposes through ransom or inflated prices, as well as exploitation through sexual and physical abuses. While the rate of exploitation varies depending on the sea route taken and the individual demographics of the migrant, exploitation is found in all parts of the crossing.130 When interviewing migrants who traveled via the Mediterranean Sea, the International Organization for Migration found that 37% of migrants have personal experiences that suggest the active presence of human trafficking and exploitation in their journey.131 The rate of exploitation seems to be highest along the Central Mediterranean route, with 73% of migrants reporting at least one instance of exploitation, not including instances of sexual exploitation.132 When sexual violence is included in the research, it is found to be highest along this Central Mediterranean route as well, with sexual violence being “commonplace.”133 Between 2014 and 2017, there has been a 600% increase in potential sex trafficking victims who have arrived to Italy via the Mediterranean.134 Over half of the children interviewed who took this route reported being held against their will at some point in their smuggling journey; the term “held against their will” was used in this survey as a key indicator to the presence of human trafficking.135 Similarly, children who took the Eastern Mediterranean route reported being held against their will at a rate twice as high as adults who took the same route.136

The different types of exploitation that migrants face at the hand of smugglers includes deception, violence, and extortion.137 Migrants are often brought to a destination contrary to the agreed-upon place, with many migrants corroborating this finding with stories of being brought to Turkey rather than Italy or France.138 Physical force including shouting, beating, and prodding is often used against migrants as well. This force creates a power dynamic that borders close to human trafficking, with violence and a lack of consent characterizing these journeys.139 The greatest cause of exploitation centers on smugglers’ desire for monetary gain; migrants pay inflated prices only to be met with hazardous travel conditions.140 When migrants cannot pay the money upfront to obtain a spot across the Mediterranean, they arrive in Europe indebted to smugglers and with no way of paying off the debt.141 This situation can lead to debt bondage or trafficking in persons.142

Vulnerability to exploitation starts even before the boats embark. Migrants waiting to travel from Libya reportedly have the highest potential to be exploited or human trafficked as compared to other transit countries.143 Refugees whose boats had been turned away on the sea (and thus were deported back to Libya) were faced with torture, detention, and monetary extortion at the hands of smugglers.144 Sexual torture is used on migrants in detention in Libya, often for humiliation or extortion purposes.145 While sexual violence tends to disproportionatly affect women, boys are reported to be just as at risk to sexual violence in their journey across the Mediterranean as girls are.146 In 2016, a doctor at the organization Save the Children reported that 50% of the unaccompanied minors he treated had sexually transmitted infections, which infections came as a result of sexual exploitation against the children en route to Italy.147

Overwhelming of Migrant Resources

Overcrowded Refugee Camps

When smugglers bring migrants to the coast of Europe, the system is unable or unwilling to support the newcomers, leading to an increase in anti-immigration sentiment, inadequate resources, full refugee camps, and a backlog on refugee applications. The most notable refugee camps for migrants arriving via the Mediterranean Sea include the Moria and Samos refugee camps in Greece.148 Since most migrants arriving by sea are doing so through illegal channels, those ashore are not ready nor equipped to help them upon their arrival. This has led to Greek refugee camps being 3 to 4 times more full than they were designed to be. The squalid conditions in the camps reflect the lack of resources available to the migrants. (A recent fire in the Moria camp has heightened this problem, leaving 13,000 migrants without shelter.149) The replacement camp that has been built can only house 3,000 migrants and the hope that this new camp would be an improvement from Moria has been dashed. In the replacement camp, food is only given once or twice per day, there is no running water, and the tents lack structural integrity.150 Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, these unsanitary conditions that migrants are arriving to have hazardous potential.

Overwhelmed Asylum System

Migrant smugglers are bringing unexpected newcomers to Europe which overwhelms the resettlement system. Almost 912,000 asylum seeker applications for the EU were still pending at the end of 2019.151 In 2019, applications for asylum rose 11% and the early months of 2020 showed a 16% increase.152 While COVID-19 has dramatically decreased the subsequent rate of applications, the number is projected to continue increasing.153 With more migrants arriving every day and with decreasing yearly resettlement quotas in host countries, backlog on legal resettlement grows. These asylum seeker applications are necessary to address in order to determine which migrants are refugees and thus allowed to stay in the EU, and which migrants are not protected under refugee status and must then be deported.154 Migrant smuggling increases the illegal channels available for entering the EU, thus overwhelming the asylum system and hindering applications by migrants attempting to gain legal resident status.

Increase in Anti-Immigration Sentiment

The increase of migrants entering Europe illegally has added to anti-immigration sentiment. In a survey of 28,000 EU citizens done by the European Commission,155 56% of Europeans agree that immigrants place a burden on the welfare system and 55% of EU citizens think that immigrants increase issues with crime.156 Xenophobia is seen manifest in the fear of cultural replacement by migrants, and 72% of French citizens believe that migrants “threaten their way of life.”157 The European Union has created a €4.7 billion trust for Africa that is supposed to help stimulate jobs and stabilize economies of countries by “addressing the root cause of instability.”158 However, this trust has been criticized as valuing tighter borders and migration control over improving the lives of the people in the countries they are helping.159 Migrant smugglers are heightening this anti-immigration sentiment by circumventing legal systems of resettlement and increasing the number of illegal migrants in the EU. The xenophobia that has previously existed against illegal immigrants is now being exacerbated as the proportion of illegal immigrants has grown due to smugglers. This anti-immigration sentiment that incoming migrants face can lead to long-term effects that prohibit their effective economic integration and social assimilation.160

Practices

Immediate Relief for Migrants En Route to Europe

One of the current best practices aimed at alleviating the issue of migrant smuggling is search and rescue missions. The most drastic consequence of migrant smuggling is death by drowning, and these missions seek to eliminate that hazard and lower the death rate of migrants who are crossing the Mediterranean Sea. However, with anti-immigration sentiment growing in many countries, states have lowered the number of state-sponsored SAR missions and have instead been focusing on surveillance and deterrence of migrants’ boats.161

In order to fill the gap in SAR missions, Medicin Sans Frontiere (also known as MSF or Doctors Without Borders) has started their own SAR missions. MSF patrols international waters off of the coast of Libya, with their focus on the most dangerous Central Mediterranean route.162 In addition to rescuing migrants from drowning, MSF operations also treat migrants for fuel burns, respiratory infections, skin disease, and any other maladies.163 Upon the migrants’ rescue, MSF team members collect the stories of the migrants and work to advocate for them following their journey at sea. Since 2016, MSF has not collected funding from the EU or any of its member states, citing their disagreement with EU immigration policies;164 the organization is now primarily funded through donations made by private individuals. MSF’s search and rescue missions represent 0.14% of their annual budget.165

Since 2015, MSF has executed 686 operations on the Mediterranean Sea, in which they have assisted over 81,000 migrants.166 They have carried out 57 medical evacuations between 2015 and 2020.167 Recent operations have been slowed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but MSF has reemphasized its duty to protect migrants at sea and was able to carry out 13 operations in 2020.168

It is important to note that these practices are effective in mitigating the immediate physical consequences of migrant smuggling. However, they do not solve the root cause of the problem, which is that migrants will continue to make these dangerous journeys if resettlement options are not open to them. No current organizational best practice is working specifically to increase worldwide resettlement quotas. These immigration policy reforms will likely happen in the legislative branches, outside of private or charitable organizations’ immediate control. However, SAR missions are needed as a short-term solution to this social issue.

Increased Legal Repercussions for Smugglers

In order to effectively solve this issue and prevent the negative consequences that follow, smugglers must be stopped upstream and charged with increased legal repercussions. Due to the highly connected nature of smuggling in the Mediterranean, often the journey at sea is only part of the operation.169 Because of this reality, land-based interventions are more effective than intervention at sea.170 Legal intervention harmonized across the Mediterranean and its surrounding countries will provide a strong deterrent to potential smugglers, as well as effectively removing key players in the web of the smuggling industry.171

The most effective legislation set in place to stop migrant smuggling is known as the Migrant Smuggling Protocol.172 This treaty was set forth by the United Nations in 2000 and has been ratified by 150 nations.173 This protocol simultaneously protects migrants from becoming liable for their journey and sets groundwork from which individual states can form their own domestic legislation.174 Because migrant smuggling is transnational, the emphasis on multi-state cooperation within the treaty creates a harmonized goal for all member parties to strive for.

The exact effects of this international legislation are difficult to observe, since no data are effectively tied to its implementation. However, following the ratification of the Migrant Smuggling Protocol, many individual countries have passed laws that follow the guidelines and goals set forth in the treaty. In 2010, Greece enacted Law 3875/2010, Ratification and Application of the UN Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime.175 This law criminalizes migrant smuggling with a penalty of up to ten years in prison.176 Italy has also added measures to fight against migrant smuggling by enacting Law 228 on Measures against Trafficking in Persons in 2003.177 This law is focused on the exploitation and human trafficking aspects of migrant smuggling, and various relief programs have been formed under the framework of this law;178 between 2000 and 2013, over 22,000 victims have been assisted by the programs established under Law 228.179

While examples such as Italy and Greece provide some evidence of the effectiveness of the UN’s Migrant Smuggling Protocol, the continued prevalence of migrant smuggling following its ratification hint at its inability for wholly effective implementation. International law can only be enforced through economic or military sanctions, and there is no plan in place to enact these sanctions against UN member states who do not implement the Migrant Smuggling Policy.180 Even if such sanctions were established, its effect on policy change would be slow, as the burden of the sanctions would fall primarily on the state’s citizens rather than its government.181 While this protocol does not have the ability to force these policy changes or force more efficient policing of smugglers, it does provide the harmonized structure that is needed to address this multinational issue. The true ground-level impact will be made through the individual actions of each member state. As more nations implement the provisions laid out in this international law, the practice of migrant smuggling will be easier to prevent and migrants involved in it will be more easily shielded from its effects.

Preferred Citation: Utsch, Lorin. “Migrant Smuggling Across the Mediterranean Sea.” Ballard Brief. April 2021. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints