Mistreatment of Wild Animals in Captivity

By Madison Coleman

Published Spring 2021

Special thanks to Erica Bassett for editing and research contributions

Summary+

Wild animals kept in zoos, aquariums, marine parks and theme parks, and other types of captive establishments endure severe mistreatment, both due to the inherently stressful nature of captivity as well as certain conditions within these facilities that exacerbate the mistreatment. The general views that society holds of animals, the ability for humans to profit from captive animals, inadequate monitoring of animal treatment, and inadequate worker training are all causes of this animal mistreatment. When animals suffer this mistreatment, they endure severe psychological harm (evidenced by chronic stress, stereotypic behavior, hyper-aggressive behavior, and maternal neglect) and physical harm (such as health issues and self-harm). They are also at risk of dying prematurely and harming or even killing humans. Environmental enrichment, captive release programs, and animal sanctuaries are practices currently being employed in an attempt to mitigate or solve the issue of animal mistreatment.

Key Takeaways+

Key Terms+

Cetaceans—Marine mammals such as whales and dolphins.1

APHIS—Animal Plant and Health Inspection Services; a federal body under the US Department of Agriculture that sets regulatory standards for facilities, operations, health, husbandry, sanitation, and transportation of zoo animals.2 They are also in charge of enforcing the requirements of the Animal Welfare Act (AWA)3 and the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA).4

WAZA—World Association of Zoos and Aquariums; an international body that creates guidelines for optimal wild animal care in zoos and aquariums. WAZA cannot enforce these guidelines; zoos and aquariums voluntarily join WAZA and choose to follow its guidelines.5

AZA—American Zoo and Aquarium Association; a federal body that sets voluntary standards for animal care in zoos and aquariums and accredits organizations if they meet the credentials.6

AWA—Animal Welfare Act; a federal law that protects captive animal welfare by establishing standards for care. These standards are enforced by the Animal Plant and Health Inspection Services (APHIS).7

MMPA—Marine Mammal Protection Act; a federal law that limits the taking or importing of marine mammals except in the case of government-approved permits. The Animal Plant and Health Inspection Services (APHIS) is in charge of issuing these permits and enforcing the MMPA’s regulations.8

Stereotypies or stereotypic behavior—“Repetitive behaviors induced by frustration, repeated attempts to cope, and/or CNS dysfunction.” These behaviors have no apparent goal or function, and are uncommon in non-captive wild animals.9

Zoochosis—A condition in which a zoo animal frequently exhibits stereotypic behavior.10

Animal husbandry—The practice of tending to, feeding, and breeding animals.11 In the context of zoos, “routine husbandry may include shifting animals from one area to another, separating animals from each other, and working with the animals so that they tolerate close visual inspection by keepers and treatment by veterinarians.”12

Inbreeding depression—When a population’s ability to survive and reproduce is decreased due to frequent mating between relatives.13

Environmental enrichment—“An animal husbandry principle that seeks to enhance the quality of captive animal care by providing the environmental stimuli necessary for optimal psychological and physiological well-being.’’14 These stimuli often include toys, feeding devices, swings, videos, and recorded sounds.15

Allostatic load—“The cumulative adverse effect on the body when allostasis occurs too frequently (as when the body is subjected to repeated stressors) or is inadequate.”16

Conspecifics—Animals belonging to the same species.17

Learned helplessness—“A mental state in which an organism forced to bear aversive stimuli, or stimuli that are painful or otherwise unpleasant, becomes unable or unwilling to avoid subsequent encounters with those stimuli, even if they are ‘escapable,’ presumably because it has learned that it cannot control the situation.”18

Logging—Listlessness and immobility, such as when cetaceans will float on the surface of the water without moving for hours at a time.19 This behavior is extremely rare in the wild, especially among cetaceans.20

Zoothanasia—The practice of killing a healthy captive animal because the management of the establishment has defined the animal as “surplus” or “unneeded.”21

Context

Q: What animals are considered wild animals?

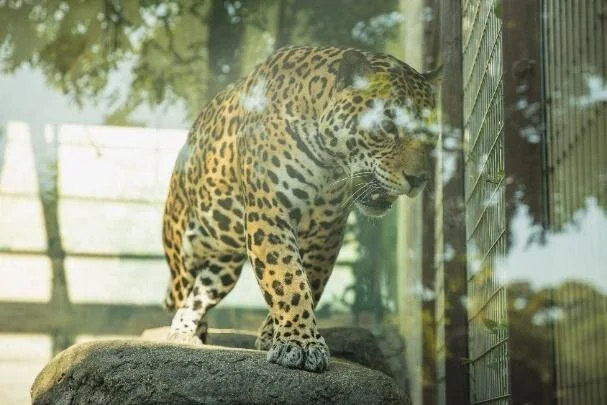

A: Wild animals are those who belong to a species that is adapted to live outside of captivity, whether or not they were born in captivity. In contrast, domesticated animals, such as pets and farm animals, have been selectively bred over a very long period of time for milder temperaments and for the ease of human handling.22, 23 Research shows that even after generations spent living and breeding in captivity, wild animals still do not adapt to captivity and do not demonstrate characteristics of domestication; much longer periods of time and artificial selection are required for domestication.24

Q: In what kinds of facilities are captive animals held and how did they get there?

A: Captive facilities that keep wild animals include zoos, aquariums, marine parks and theme parks, circuses and travelling shows, scientific research labs, rehabilitation centers and sanctuaries, and private homes where wild animals are kept as pets.25 Animals may come to live in these facilities after being captured from the wild, or by being born in captivity. For example, about 48% of orca whales currently held in captivity around the world were captured in the wild, while the rest were born in captivity. At least 166 orcas have been taken from the wild since 1961, and 26% of these were captured at a young age.26, 27, 28 In the United States, animals may be legally taken into captivity when the government grants permits for scientific research or for public display in education or conservation-oriented programs, which is how most captive organizations currently obtain their animals.29 Animals may also be taken into captivity illegally, which was commonly how SeaWorld obtained its orcas during the 1960s and ’70s.30

Q: In what ways are wild animals mistreated in captivity?

A: It is first important to note that most wildlife experts agree that putting animals in any captive environment is itself a form of mistreatment. This is because captivity enforces conditions upon wild animals in which they are not adapted to thrive. Neuroscientist and animal behavior expert Lori Marino stated: “All wild animals in captivity are subjected to (a) restrictions and loss of control, (b) forced interspecies interaction and intrusion either through performances or by being put on display, and (c) monotony, all while held in artificial settings that have little resemblance to habitats that support their evolutionary heritage and adaptations.”31 However, the mistreatment that animals face within captivity can be further exacerbated depending on the conditions within the facility and the extent of the mismatch between the captive situation and the animal’s adaptations.32 As such, this brief will discuss the harm of captivity as a whole as well as the specific conditions of captivity that further decrease animal well-being.

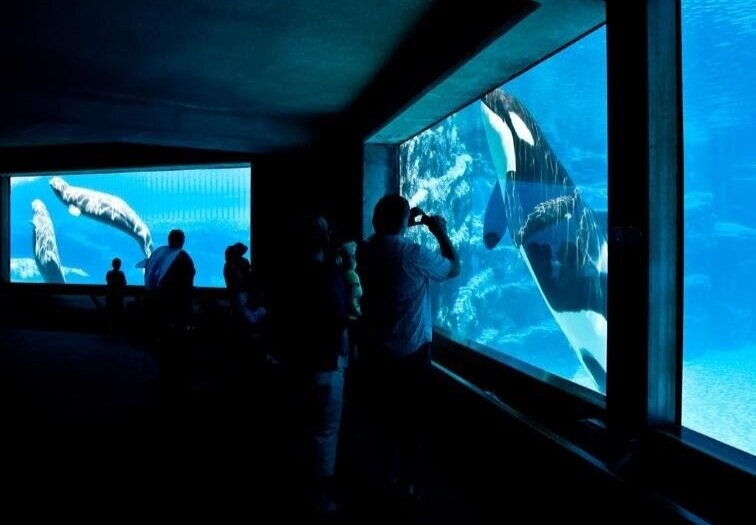

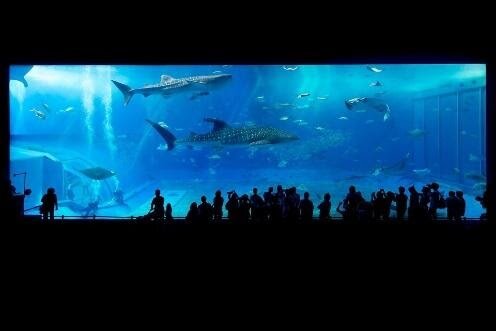

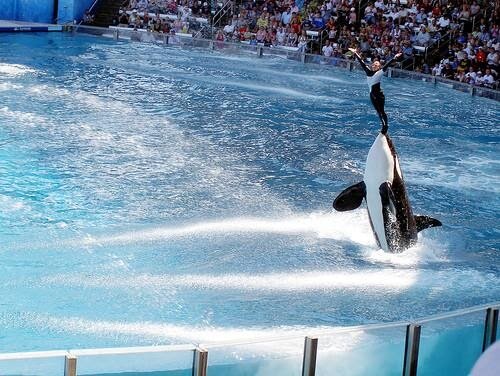

Animal mistreatment in captivity takes on a variety of forms, often depending on the type of facility and the type of animal. Blatant physical abuse such as beating or kicking, though not unheard of, is much less common (or at least much less reported) than mistreatment in subtler, more hidden forms.33, 34, 35 One of the most common forms of mistreatment is inadequate and limited living conditions. For example, tigers and lions have about 18,000 times less space in their captive enclosures than what they would have in the wild, and polar bears have one million times less space.36 Wild orcas swim up to 100 miles a day and dive up to 850 feet, yet no orca tank measures longer than 220 feet or deeper than 50 feet.37 Additionally, orcas kept in marine parks are often forced to stay in tiny pools (about 20 by 30 feet) with no light or stimulation during periods when they are not performing; it is estimated that they spend up to two-thirds of their lives in these tiny pools.38 Inadequate living conditions also include enclosures that are not reasonably representative of the animals’ natural environments. For example, most enclosures for callitrichid monkeys do not provide dense tangles of vegetation even though this is where this species would spend 89% of their time in the wild.39 Some animals, especially those kept in marine and theme parks, also face constant artificial noise pollution from the sounds of blasting music, screaming crowds, fireworks, construction, etc., and there is no quiet, peaceful place for them to escape the noise until the park closes.40

Another common type of animal mistreatment is separating the animal from their family or other animal companions and forcing them into artificial social groups. For species who are highly social and are adapted to spend most of their lives with their family members (such as CetaceansMarine mammals such as whales and dolphins.1), this can be incredibly stressful and emotionally devastating.41, 42, 43 This is evidenced by instances of distress vocalizations, escape attempts, and increased heart rate and stress hormone secretion among animals who are separated from their companions.44

Additionally, establishments that allow for close interaction between the visitors and the animals are enforcing additional mistreatment on the animals because these interactions are inherently stressful for the animal. A 2019 worldwide study found that 75% of zoos and aquariums offered at least one type of animal-visitor interaction experience that went against the guidelines established by the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZAWorld Association of Zoos and Aquariums; an international body that creates guidelines for optimal wild animal care in zoos and aquariums. WAZA cannot enforce these guidelines; zoos and aquariums voluntarily join WAZA and choose to follow its guidelines.5).45 See graphic for examples of these types of interactions and results from this study.

Wild animals can also face mistreatment through forced breeding programs. The training process for artificial ejaculation can often be degrading to the animal by training the male to present his penis for manual stimulation or even conditioning him to become aroused by animals of other species.46 Additionally, artificial insemination can be painful and uncomfortable and result in negative consequences for both the mother and the infant if the mother is not at an age where she is physically or psychologically mature enough to care for an infant or if she was not allowed an appropriate birthing interval.47, 48, 49

Other types of animal mistreatment in captivity include some feeding and training practices. For example, many wild animals spend most of their day hunting or foraging for food, but in some captive facilities, food is just given to them, causing boredom and psychological distress because they are adapted to forage or hunt. Moreover, the food provided may be inadequate; orcas are often fed frozen fish, which have a lower water content than fresh fish and can thus lead to chronic dehydration.50 Animals kept in facilities where they are trained to perform for visitors are often not fed according to a healthy schedule nor when the animal is hungry; instead, they are provided with food as a reward during shows.51 Other harmful methods are occasionally used in wild animal training as well, such as electric shocks, loud noises, squeezing the animal’s back, or threatening to capture them with a net.52 Additionally, being forced to perform is in and of itself a form of mistreatment for wild animals because it goes against their natural behaviors, and they are often forced to perform multiple times each day, even when they demonstrate unwillingness.53

Q: Who is mistreating captive animals?

A: Those who are in charge of running captive establishments are the ones who make decisions about how the animals will be treated, what training and feeding techniques will be used, what the enclosures will look like, and what breeding programs are employed. Therefore, even though individual workers may often be the ones carrying out the mistreatment since they are interacting closely with the animals, those in executive roles at captive establishments are primarily responsible for the mistreatment of wild animals.54, 55, 56

Q: What kinds of animals are most commonly mistreated?

A: No studies have been conducted to find which animals and species are most commonly mistreated. However, research does demonstrate that large, wide-ranging, highly intelligent, socially complex, and self-aware animals are most likely to suffer a decrease in well-being from captivity.57 This includes cetaceansMarine mammals such as whales and dolphins.1, primates, elephants, bears, and big cats.58,59 These animals are more likely to suffer because they have more complex needs that cannot be met, or even approximated, in captive establishments. Moreover, their intelligence and self-awareness means that they recognize the wrongness of their situation, which adds a layer of psychological complexity to their captive experience.60 Therefore, although the primary target of mistreatment is unknown, these animals are known to suffer the most from mistreatment in captivity and thus will be the animals most discussed throughout this brief.

Q: Is the issue of animal mistreatment improving?

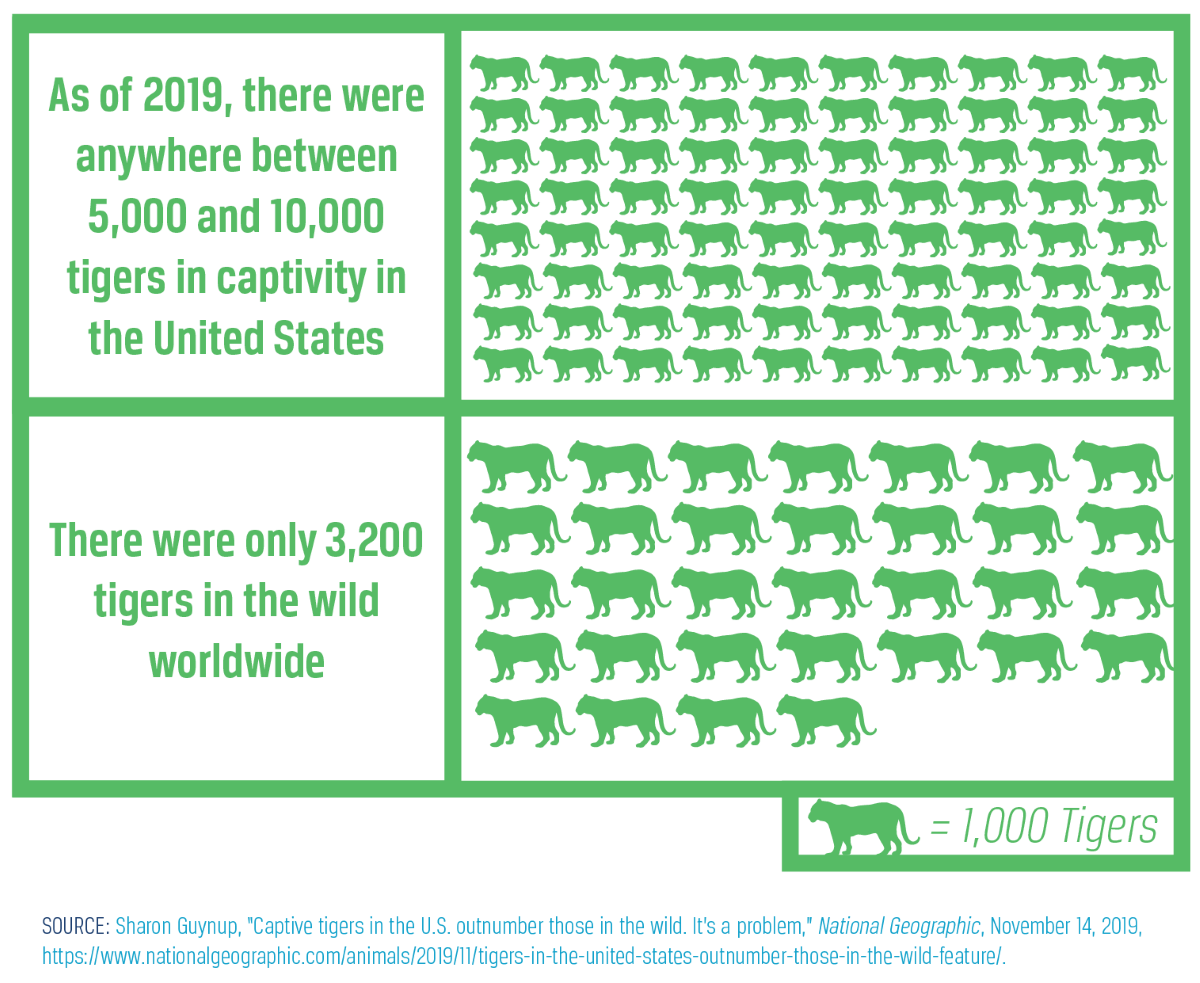

A: Although there have been great improvements made to captive animal welfare in recent years, animal mistreatment continues to be a major issue.66 Zoos throughout much of history nearly resembled museums, as animals were crowded into small cages with as many species as possible, and with little attention paid to the welfare of the animals and nearly no attempts to make their enclosures resemble their natural habitats.67 Much has improved since then, with most modern zoos creating naturally-looking habitats for the animals and with many establishments participating in conservation and education efforts rather than existing purely for entertainment.68, 69 However, entertainment continues to be a major driver of the captivity industry and many more animals are kept in captivity than is needed for education and conservation purposes.70 For instance, as of 2019, there were between 1.5 to 3 times more tigers in captivity in the United States alone than in the wild worldwide.71

Throughout the 2010s, captive animal mistreatment has been brought to the public’s attention more than ever before.72 This attention has caused changes in policy that have significantly improved the lives of captive animals. For example, the backlash that SeaWorld received following the release of the highly successful documentary Blackfish in 2013, which addressed SeaWorld’s mistreatment of orcas, pushed the company to modify its orca shows so that they were more educational and trainers interacted less with the whales.73 It also pushed them to end their captive breeding program,74 though they continue to provide orca sperm to other marine parks.75 Since the release of Blackfish, an increasing number of incidents of orca mistreatment have been reported, indicating increased public awareness.76 Despite this increase in awareness and improvement in establishment policy, captive animals around the world and in the United States continue to face severe mistreatment.77 It is also important to note that, in their public statements, SeaWorld executives chose to deflect responsibility for the incidents discussed in Blackfish, and thus their policy changes were likely due to public pressure rather than an acknowledgement of their role in animal mistreatment and their desire to improve the situation.78

Q: How does the United States compare to other countries in regards to animal mistreatment?

A: Due to inadequate record-keeping of instances of animal mistreatment, there are no statistics that demonstrate the extent of mistreatment in the United States as compared to other countries. However, most reports and studies indicate that animal mistreatment is about as severe and widespread in the United States as any other high-income country, such as Canada and many of the Western European nations.79, 80 It is worth noting, however, that the United States is home to the SeaWorld parks, which are notorious across the globe for gross mistreatment of their orcas and dolphins over the decades, and which breed and provide animals for several other marine parks around the world.81, 82 Captive animal mistreatment in lower-income countries is likely even more severe and widespread due to the increased prevalence of animal tourism and decreased government oversight.83, 84, 85

Q: Who monitors and reports on animal mistreatment in captivity, and what policies protect captive animals?

A: Policies and organizations operate on the international, federal, state, and local levels to protect captive wild animals. There is currently no global body that regulates all wildlife tourism, but the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) provides guidelines for optimal animal care. However, joining WAZAWorld Association of Zoos and Aquariums; an international body that creates guidelines for optimal wild animal care in zoos and aquariums. WAZA cannot enforce these guidelines; zoos and aquariums voluntarily join WAZA and choose to follow its guidelines.5 is optional for all captive organizations, so they are not required to follow these guidelines.86 The same is true for the American Zoo and Aquarium Association (AZAAmerican Zoo and Aquarium Association; a federal body that sets voluntary standards for animal care in zoos and aquariums and accredits organizations if they meet the credentials.6) and the Alliance of Marine Mammal Parks and Aquariums (AMMPA), the two prominent animal welfare regulatory organizations in the United States.87 On the federal level, the Animal Welfare Act (AWAAnimal Welfare Act; a federal law that protects captive animal welfare by establishing standards for care. These standards are enforced by the Animal Plant and Health Inspection Services (APHIS).7) protects zoo animals88 and the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPAMarine Mammal Protection Act; a federal law that limits the taking or importing of marine mammals except in the case of government-approved permits. The Animal Plant and Health Inspection Services (APHIS) is in charge of issuing these permits and enforcing the MMPA’s regulations.8) limits the taking and importing of marine mammals.89 The Animal Plant and Health Inspection Services (APHISAnimal Plant and Health Inspection Services; a federal body under the US Department of Agriculture that sets regulatory standards for facilities, operations, health, husbandry, sanitation, and transportation of zoo animals.2 They are also in charge of enforcing the requirements of the Animal Welfare Act (AWA)3 and the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA).4) is the federal body charged with inspecting captive facilities and ensuring their adherence to the AWA and the MMPA.90, 91 The limitations and efficacy of these policies and organizations will be discussed later in this brief.

Partially due to the lack of accurate and regular record-keeping by governments and institutions—and partially due to the negative stigma that surrounds establishments known to mistreat animals and the secretive nature of many forms of animal mistreatment—there is a dearth of large-scale, quantitative research regarding animal mistreatment in captivity. As such, this brief will utilize a variety of qualitative and small-scale studies as well as reports from animal activist organizations in order to provide evidence for the occurrence of animal mistreatment and its causes and consequences, with the acknowledgement that the information in these reports may be biased.

Contributing Factors

Societal Views on Animals

A significant contributor to the widespread mistreatment of wild animals in captivity is how human society as a whole has historically viewed and continues to view animals as largely existing for human benefit and entertainment. Animals have been kept in captivity in zoo-like establishments, such as menageries, as far back as Ancient Egypt,92 and for much of human history were kept to demonstrate the power and status of kingdoms or leaders.93 Although much has changed since then, this history of animals being objects of status or entertainment has established a precedent for the continuing captivity and mistreatment of animals. It has created a culture wherein the public cannot imagine not having access to viewing animals in captivity as a recreational activity and accept captivity as normal and acceptable.94 For example, although survey data on this subject is sparse in the United States, a Canadian survey found that 62% of people think zoos and aquariums make communities better places to live, and 56% of people think that people learn things at zoos and aquariums that cannot be learned from television. Moreover, 40% of people say it is acceptable to keep non-endangered and non-injured animals in captivity.95 These positive attitudes of captive establishments, even when there is no clear reason for keeping the animals in captivity besides human entertainment, perpetuate the issue of captivity and animal mistreatment because they drive the public to continue to support the captive industry.

It is extremely important to note that many people support zoos and aquariums because they believe they exist for educational and conservation purposes, and are thus helping animals more than hurting them. One online poll found that 52% of responders agreed that zoos help to protect species and educate the public on poaching, habitat loss, and preservation.96 However, the impact that captive establishments have on education and conservation is significantly less than the public believes. One study found that children better understood and appreciated animal adaptation, ecosystem significance, and threats to animal survival when looking at museum exhibits than visiting zoos.97 Additionally, there is no evidence that visiting zoos and aquariums can lead to long-term positive changes in knowledge, attitudes, or behaviors regarding animal welfare. If anything, they can have a negative effect by sending the message that animals exist for the purpose of human commoditization and exploitation.98 Moreover, only about a third of zoo visitors go to learn about the animals, and even less go to learn about conservation; the grand majority visit purely for entertainment.99 Aware of this public appreciation for entertainment, zoos often set aside conservation efforts in order to focus on the entertainment aspects that will attract visitors, yet are worse for the animals.100 In fact, fewer than 5-10% of zoos and aquariums are involved in wildlife conservation programs, and those that are spend only a miniscule fraction (estimated to be less than 3%101) of their income on these programs.102

Although some captive establishments certainly do dedicate more of their time and resources to conservation and education,103 the impact of the captive industry as a whole is extremely minimal because its main purpose is entertainment. Societal views on animals have led to the prioritization of entertainment by the public and thus the captive industry, which causes a perpetuation of animal captivity and mistreatment and significantly decreases any positive effects that the industry could have on animal welfare.

Profitability of Animals

One of the most significant reasons that animals continue to be held in captivity is that this practice is monetarily profitable for the captivity industry. While animals in the wild do not bring any profit to organizations, those in captivity can be held in enclosures so that people will pay to see or even breed them. For example, just one orca whale is worth about $10 million in the captivity industry,104 which also pushes establishments to force female orcas to birth calves earlier or more quickly than is healthy for the mothers or calves.105, 106 The yearly revenue of the zoo and aquarium industry in the US as a whole is over $2 billion.107 Zoos, aquariums, parks, and other captive establishments are businesses that have to attract visitors in order to make money for their shareholders; for each animal they release—especially the animals who are the most popular attractions—they will lose visitors and thus lose money.108

The profitability of animals is also a contributor to the mistreatment of animals within captive establishments. One of the reasons that animal enclosures are not sufficiently large for the animals is because the establishment would have to pay more money to expand the enclosures; although no specific statistics are available on this topic, it is safe to assume that it is more cost efficient to keep the enclosures small even though it is detrimental to the animal.109 Additionally, many marine park pools contain no objects for mental stimulation, leading to boredom and stereotypies“Repetitive behaviors induced by frustration, repeated attempts to cope, and/or CNS dysfunction.” These behaviors have no apparent goal or function, and are uncommon in non-captive wild animals.9 for many dolphins and whales. Adding more stimulating objects (even something as simple as rocks), would be more difficult and time-consuming for the workers to clean, suggesting that cost efficiency takes precedence over animal welfare.110

The profits that animals produce for establishments can also lead to mistreatment because people are willing to pay more for exhibits that are more entertaining, but these more entertaining exhibits are worse for the animals.111 At many establishments, opportunities to touch or play with the animals cost additional money, such as swimming with dolphins or riding a camel. Visitors are often willing to pay high prices for these attractions because they are more enjoyable than just watching the animals, and thus establishments continue to provide these experiences because it is profitable for them.112 However, these experiences are inherently stressful for the animals and are thus considered mistreatment. Additionally, people are willing to pay more to watch the animals perform in shows or do tricks than just watch them walk around or lie in their enclosure. This is exemplified by the ticket price differences between zoos and establishments where they train animals to perform, such as marine parks and circuses. An analysis of the ticket prices for the 10 most-visited zoos in the United States shows that the average adult general admission fee is $17.29, with 4 out of these 10 charging no fee.113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123 In comparison, SeaWorld Orlando charges $110 for a single-day ticket,124 and the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus charged about $43 per show before closing in 2017.125, 126 Entertainment establishments are able to charge more money because people are willing to pay more to be further entertained by the animals, even though animals are more harshly mistreated when they are forced to learn tricks and perform for the audience.127

Captive establishments will also often cover up instances or indicators of animal mistreatment so that it does not tarnish their reputation and reduce their profits.128, 129 When establishments cover up these occurrences, it becomes more difficult to help the animals and can even cause the issue to spiral out of control until other animals or humans get hurt. For example, when an animal is acting aggressively, the institution could identify the triggers for this aggressive behavior and take precautions to reduce the animal’s stress and prevent further acts of aggression. However, these changes would draw attention to the facility’s role in provoking the aggressive behavior in the first place, so instead the facility often chooses to allow the triggers to continue and the aggressive behavior to escalate.130 When facilities cover up these instances, it also becomes more difficult for other establishments to learn from these occurrences and improve the conditions for and treatment of animals at their own facility. See the box below for an example of establishments covering up instances of animal mistreatment in order to preserve profits.

Inadequate Monitoring of Animal Treatment

Another significant contributor to the mistreatment of wild animals in captivity is the inadequate policies and implementation of policies regarding animal treatment. APHISAnimal Plant and Health Inspection Services; a federal body under the US Department of Agriculture that sets regulatory standards for facilities, operations, health, husbandry, sanitation, and transportation of zoo animals.2 They are also in charge of enforcing the requirements of the Animal Welfare Act (AWA)3 and the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA).4 has been shown to be ineffective at ensuring that facilities are complying with the regulations outlined in the AWA and the MMPAMarine Mammal Protection Act; a federal law that limits the taking or importing of marine mammals except in the case of government-approved permits. The Animal Plant and Health Inspection Services (APHIS) is in charge of issuing these permits and enforcing the MMPA’s regulations.8, allowing animals to die from the negligence of their captive facilities.131 This inefficiency is likely due to the fact that APHIS is an extremely overwhelmed government body in charge of regulating a multitude of environmental issues.132 As of 2004, APHIS employed only 104 inspectors, but was in charge of inspecting over 2,000 facilities. The organization simply does not have the resources needed to adequately monitor animal treatment.133 When animal mistreatment goes unnoticed by those who have the power to enforce regulations, this allows mistreatment to continue because the establishments responsible are not facing the necessary consequences. Other organizations that set guidelines for animal mistreatment, such as the WAZAWorld Association of Zoos and Aquariums; an international body that creates guidelines for optimal wild animal care in zoos and aquariums. WAZA cannot enforce these guidelines; zoos and aquariums voluntarily join WAZA and choose to follow its guidelines.5 and the AZA, lack the power to enforce these guidelines, and gaining membership into these organizations is voluntary, meaning no captive establishment is forced to abide by these guidelines.134, 135 Moreover, less than 10% of American zoos are accredited by the AZAAmerican Zoo and Aquarium Association; a federal body that sets voluntary standards for animal care in zoos and aquariums and accredits organizations if they meet the credentials.6, meaning over 90% of zoos face very little oversight and do not have stringent guidelines to abide by.136

Not only are federal regulatory bodies and policies inadequate, but many state laws fail to protect animals from mistreatment. Six US states have created policies that exempt the exhibition of animals from the scope of cruelty, meaning even the worst means and conditions of exhibition cannot be considered animal cruelty.137 Additionally, laws between states vary dramatically in their coverage and sentencing provisions, and local law enforcement bodies with inadequate resources are often put in charge of enforcing state animal welfare policies.138

Inadequate Worker Training

While most forms of mistreatment come from the animal trainers and caretakers, as they are the ones working closely with the animals, this mistreatment is often unintentional and perpetuated due to the actions and policies of the managers of the facility. Much of the time, trainers and caretakers who use harmful training or feeding methods have not been adequately educated to realize that these practices are detrimental to the well-being of the animals.139 Mistreatment, then, is commonly a result of a lack of knowledge and adequate training for those who work closely with the animals—training that should be provided by the captive establishments or required before workers are hired. This cause of mistreatment is much more common in commercial entertainment facilities, such as marine and theme parks, than zoos and aquariums.140, 141 However, inadequate worker training in zoos and aquariums has led to forms of mistreatment such as incorrect animal diets or ineffective environmental enrichment devices“An animal husbandry principle that seeks to enhance the quality of captive animal care by providing the environmental stimuli necessary for optimal psychological and physiological well-being.’’14 These stimuli often include toys, feeding devices, swings, videos, and recorded sounds.15,142, 143 since workers with more extensive training on animals’ needs and behavior would have been able to identify these issues. For example, in 2015, a zoo in Chicago lost its entire stingray population (54 stingrays) because the workers allowed the oxygen levels in the tank to drop too low.144

In many marine parks, trainers are not required to obtain any kind of educational degree relating to animal behavior; the necessary credentials for being a trainer have more to do with personality and swimming ability.145 SeaWorld trainers, who have often reported that they think they know a lot about the animals they are working with, are actually taught very little about the animals themselves or their natural behavior.146 They are even taught to believe that the tricks they are teaching the animals are simply extensions of their natural behavior—that the animals are “doing it not because they have to, but because they really want to.” The trainers, then, pass on this same narrative to the visitors.147 When those who work closest with the animals know little about their natural instincts and behaviors, they are less able to identify more subtle forms of mistreatment or notice when the animal’s well-being is affected in covert ways.

Consequences

Psychological Harm

The mistreatment that animals undergo in captivity most often results in harm to their psychological health. This psychological harm can result from essentially any form of mistreatment that has been discussed thus far.

Chronic Stress

One of the most common manifestations of psychological harm in captive animals is chronic stress. Research demonstrates that many animals in captivity experience a build-up of repetitive acute stressors from the different forms of mistreatment, which then creates a consistently high allostatic load“The cumulative adverse effect on the body when allostasis occurs too frequently (as when the body is subjected to repeated stressors) or is inadequate.”16. For example, 42% of studies in a meta-analysis found increased GC concentrations in wild animals in captivity—an indicator of long-term exposure to stress.148 Evidence of this chronic stress is also seen in increased levels of anxiety, cognitive impairment, mood dysregulation, and even symptoms of posttraumatic stress.149 One source of this stress is sensory overloads from excessive, abnormal sounds.150 Captive animals also suffer from social stressors when they are placed in the same enclosures with animals with whom they have not built close relationships, and when they are deprived from the strong social networks needed to psychologically thrive.151

Another source of stress for many wild animals is the frequent handling by and proximity to humans. One study of captive wombats showed that wombats who were handled regularly demonstrated increased cortisol secretion, defecation, and stereotypic behavior (all indicators of high stress levels) as compared to wombats who were handled only for regular animal husbandryThe practice of tending to, feeding, and breeding animals.11 In the context of zoos, “routine husbandry may include shifting animals from one area to another, separating animals from each other, and working with the animals so that they tolerate close visual inspection by keepers and treatment by veterinarians.”12 purposes.152 These interactions often lead to learned helplessness“A mental state in which an organism forced to bear aversive stimuli, or stimuli that are painful or otherwise unpleasant, becomes unable or unwilling to avoid subsequent encounters with those stimuli, even if they are ‘escapable,’ presumably because it has learned that it cannot control the situation.”18, wherein the animals seem to “get used to” human interaction because they decrease their resistance to them over time, but in reality the animals have given up resisting because they learn that they have no control over these unpredictable and unpleasant experiences. Learned helplessness is a significant indicator of high levels of stress and low psychological well-being because it can lead to depression, anorexia, immune system dysfunction, and loggingListlessness and immobility, such as when cetaceans will float on the surface of the water without moving for hours at a time.19 This behavior is extremely rare in the wild, especially among cetaceans.20.153

Stereotypic Behavior

Stereotypic behavior“Repetitive behaviors induced by frustration, repeated attempts to cope, and/or CNS dysfunction.” These behaviors have no apparent goal or function, and are uncommon in non-captive wild animals.9, also referred to as zoochosisA condition in which a zoo animal frequently exhibits stereotypic behavior.10, is very common among captive animals and though these behaviors may not always be harmful in and of themselves, they are indicators of low psychological well-being.154 Frequent examples of stereotypies“Repetitive behaviors induced by frustration, repeated attempts to cope, and/or CNS dysfunction.” These behaviors have no apparent goal or function, and are uncommon in non-captive wild animals.9 include pacing, chewing on the edges of tanks or enclosures, regurgitating food (with no identifiable physiological motive), and even self-mutilative behaviors such as self-biting or hair-plucking.155, 156 These behaviors arise when the animals are deprived of adequate mental stimulation and when they are overloaded by stressful stimuli; they become so bored or so stressed to the point that their brain development is affected and triggers abnormal behaviors as a coping mechanism.157, 158 Though the frequency of stereotypic behavior ranges widely depending on the species and the individual animal, a range of studies show that it is common among most animals, especially more intelligent and self-aware animals.159 For example, a meta-analysis found documentation of stereotypies in over 85 million farm, lab, and zoo animals,160 and all elephants, cetaceansMarine mammals such as whales and dolphins.1, and primates in captivity exhibit some form of abnormal behavior (which is classified as either stereotypies or hyper-aggression, as discussed below).161 Additionally, stereotypies are more common among animals who were separated from their mothers early in life and who are kept in smaller, simpler enclosures or with fewer companions.162 About 68% of situations that have been found to cause or increase stereotypies have also been found to decrease welfare in other areas of the animals’ lives, further demonstrating how stereotypies are indicators of negative well-being.163

Hyper-Aggressive Behavior

Many captive animals express hyper-aggressive behavior, both toward conspecificsAnimals belonging to the same species.17 and toward humans. It should be noted that many wild animals are aggressive whether in captivity or in their natural environments due to their behavioral adaptations; hyper-aggression, however, indicates behavior that is more aggressive than what is normal for that species’ wild counterparts, and thus is an indication that their mistreatment and the stress of their captive situations has exacerbated their aggression.164 For example, in a survey of 35 zoos, at least 28% of elephants were found to have been injured by other elephants, which significantly exceeds the level of aggression exhibited by wild elephants.165

One cause of this hyper-aggression can be forcing animals with no social connection to live in close quarters with one another. For example, orcas are highly social animals who form deep connections with their pods in the wild; different pods even have different “dialects,” making it difficult or impossible for orcas from pods located far away from one another to communicate. Nevertheless, marine parks will often force orcas from different pods and ecotypes to live in close quarters with one another; the stress of not being able to communicate with or form a social bond with these conspecificsAnimals belonging to the same species.17 often results in hyper-aggression, which includes teeth-raking, ramming, or tail-slapping.166, 167 Although orcas in the wild do occasionally display these behaviors, it is infrequent, short-lived, and results in no serious harm since there are social rules that prohibit serious violence and they have space to flee the conflict. In captivity, the lack of areas to flee to coupled with the stressful social conditions result in more serious bursts of hyper-aggression and thus more serious injuries.168 One ex-SeaWorld employee reported that it was not uncommon to find long strips of orca skin at the bottom of tanks from the whales peeling it off one another.169 Teeth rake marks have even been found on orca calves, which has not ever been documented in the wild.170

Maternal Neglect

Another indicator of psychological harm to captive animals is when mothers are neglectful or aggressive toward their infants due to improper breeding practices. For example, 83% of captive orcas are forced to give birth at an age younger than the average age of first birth in the wild, which means the mothers have often not yet reached sexual and social maturity. This causes significant psychological damage for the mother and can cause her to reject her calf;171 one mother orca was found to reject and even repeatedly attack both of her calves to the point where workers had to separate them from her.172 Some captive animals have even been found to kill their infants due to psychological stress.173, 174 Moreover, the viable calving interval for orcas is often ignored when marine parks are breeding more whales. This natural calving interval allows the mother to devote her attention to the calf and ensure that it has acquired adequate social and behavioral skills before turning her attention to the next calf. When breeders shorten the calving interval, this causes mothers to neglect their calves and thus the calves grow up without the necessary social and behavioral skills. This can then lead to serious psychological harm as well as other issues for the calf.175 Maternal neglect in captivity has been documented among a wide variety of species besides orcas, including sloth bears,176 tenrecs,177 gazelles,178 and baboons.179

Physical Harm

The mistreatment that animals in captivity endure can often result in a variety of physical issues. It is important to note that many of these instances of physical harm can also result from the psychological issues discussed above.

Health Issues

Animals in captivity can experience a variety of health problems as a result of mistreatment in their captive situations. These health issues vary greatly depending on the species and on the captive situation. For example, since elephants do not have large enough enclosures and the floors of their enclosures are made from inappropriate surfaces, such as concrete, they often suffer from musculoskeletal disorders such as arthritis or are made lame from foot disorders. Arthritis and foot disease are the leading causes of euthanasia in captive elephants.180 Additionally, many apes suffer from cardiovascular diseases (one of the major causes of mortality for captive great apes) due to their sedentary lifestyle and inadequate diet.181 Captive, but not wild, black rhinos have been found to suffer from inflammation and insulin resistance, likely due to metabolic problems that come from their diet and lack of exercise.182 CetaceansMarine mammals such as whales and dolphins.1 and seals often suffer from cataracts, eye lesions, and other eye diseases—which can develop into visual impairment or blindness—due to poor water quality or prolonged sun exposure and inadequate shade provided by the captive establishment.183, 184, 185

Many animals also suffer from physiological issues due to prolonged stress from captivity. Sixty-four percent of studies in a meta-analysis found a documented decrease in weight associated with captivity after an animal’s initial capture, which these studies attribute to chronic stress. In 61% of these cases, the animals never gained back the lost weight, indicating that they never adapted to the stress of captivity.186 In 17% of these 36 studies, animals gained weight after their capture, often due to excess availability to food and limited exercise; for some animals, this later resulted in DNA damage.187 In addition to changes in weight, the stress of captivity can result in immune system dysfunction, which leaves animals vulnerable to other diseases.188 Fatal diseases such as ulcerative gastritis, perforating ulcers, and cardiogenic shock in cetaceansMarine mammals such as whales and dolphins.1, as well as tuberculosis in elephants, have been found to be tied to immunodeficiency-based infections.189 Inadequate conditions in captivity have also been tied to reduced reproductive capacity, anatomical changes (such as reduced hippocampal volume), kidney lesions, and DNA damage in red blood cells.190 It is important to note that many of these health issues have been found to persist even after animals have been released back into the wild, indicating severe, permanent physiological damage.191

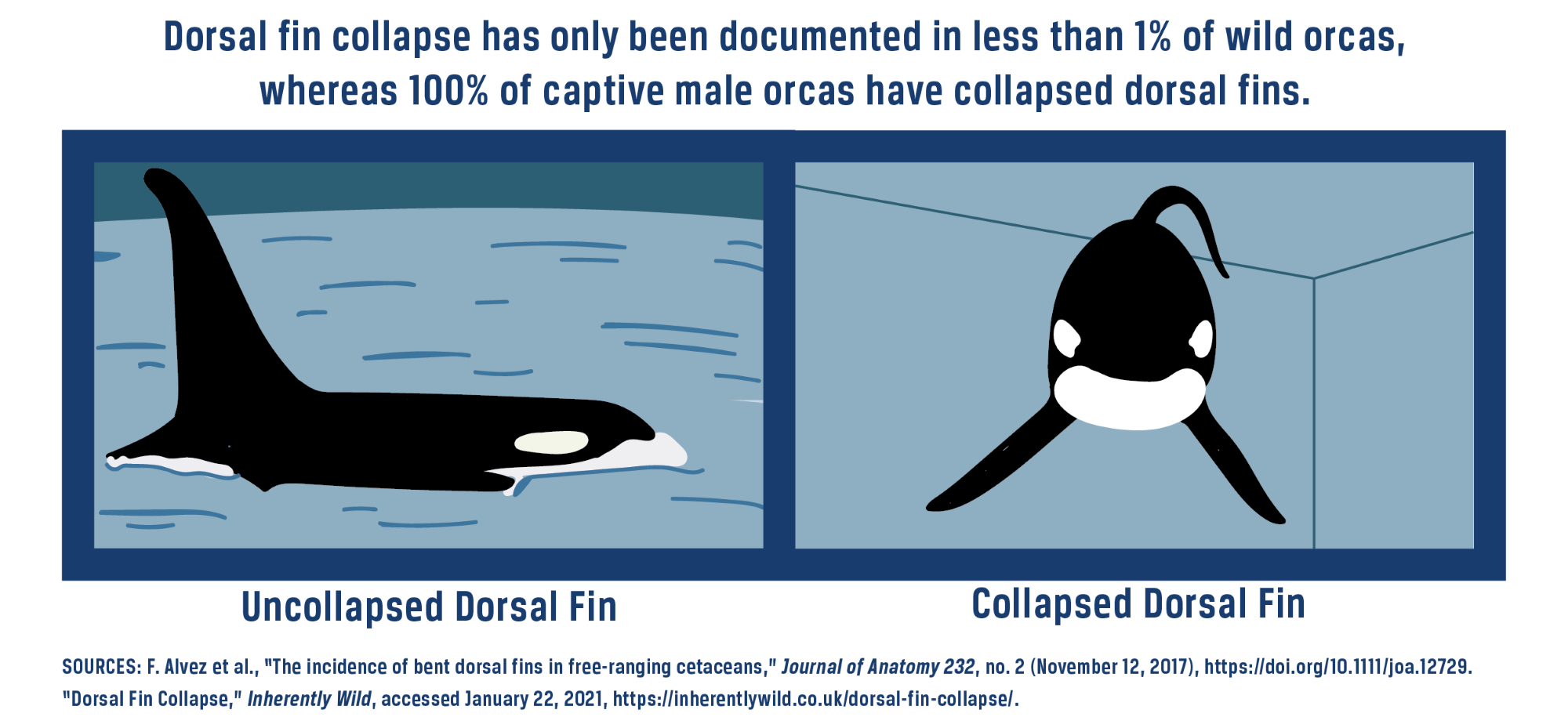

Another indicator of poor physical health in captive animals is physical abnormalities. For example, the dorsal fins on orcas are made of fibrous tissue that is held upright by the deep water pressure and fast speeds at which wild orcas swim. Because of the inadequate tank sizes and depths, however, this tissue can wear down and cause the dorsal fin to collapse. This occasionally happens in wild orcas due to injuries, exposure to oil spills, or stress and old age; however, it has only been documented in less than 1% of wild orcas,192 whereas 100% of captive male orcas have collapsed dorsal fins.193 Another example of a physical abnormality is a crease that is commonly seen in the neck of captive dolphins; this is caused by dolphins having to unnaturally lift their heads above the water for much of their lives and remain vertical to perform tricks, when they would spend most of their lives horizontal and under the water in the wild.194 Both dolphins and orcas often experience oral degradation, which means that their teeth have been worn down from the stereotypic behavior“Repetitive behaviors induced by frustration, repeated attempts to cope, and/or CNS dysfunction.” These behaviors have no apparent goal or function, and are uncommon in non-captive wild animals.9 of chewing on the concrete; over 60% of captive orcas in the US and Spain have fractured teeth and 24% have teeth worn down to the gingiva.195 This oral degradation puts the cetaceansMarine mammals such as whales and dolphins.1 at risk for infections and often means they have to undergo an extremely painful pulpotomy procedure as well as face routine treatment with antiseptics and antibiotics that can alter their immune system functioning.196, 197

Self-Harm

Another form of physical harm that many captive animals suffer from is self-harm. As previously mentioned, many captive animals display self-mutilative behavior—classified as zoochosisA condition in which a zoo animal frequently exhibits stereotypic behavior.10—as coping mechanisms. This self-harming behavior can come in the form of refusing to eat, biting or chewing on the tail or leg, and over-grooming to the point where they are pulling out hair and feathers and causing bald patches or irritated and broken skin.198, 199 Another example of self-harm is that whales have been found to ram their head or body into the walls or gates of their tank. One orca at Miami Seaquarium was recorded ramming his head into the wall on two separate occasions, sustaining a serious injury the first time, and killing himself the second time due to a brain aneurysm from the force. Dolphins at the Miami Seaquarium have also been observed repeatedly hitting their heads on the bottom of the tank floor.200

Additionally, some cetaceansMarine mammals such as whales and dolphins.1 have been observed self-stranding, wherein they jump up onto the show platform located out of the water and stay there for prolonged periods of time—sometimes up to 30 minutes. This can be life-threatening as their internal organs are crushed and muscles are damaged from staying out of the water for so long, or they could die from dehydration or heat exhaustion. Due to repetitive self-stranding despite these adverse health effects—and due to the fact that self-stranding is virtually unheard of in the wild—some researchers classify this as suicidal behavior driven by the constant stress that these animals face in captivity.201 Similarly, dolphins at Gulf World Marine Park in Florida were found to frequently jump outside of their tanks; it became so common for trainers to come to the park in the morning and see beached dolphins on the concrete pathways around the tanks that the park ended up having to build metal rails over the tops of the show tanks.202

Premature Deaths

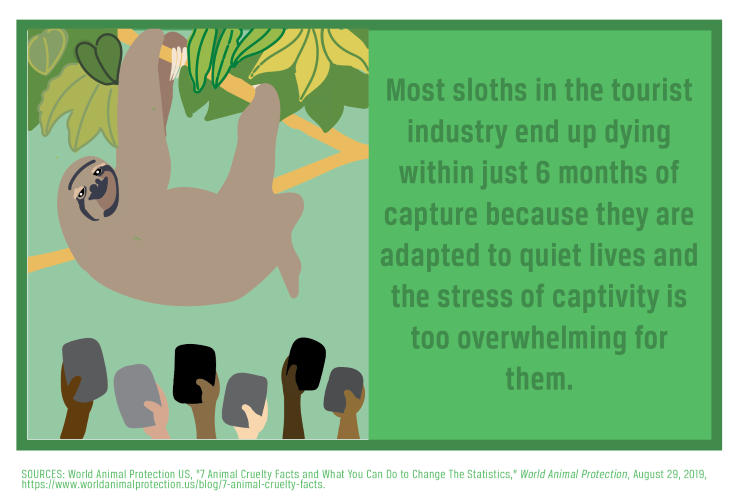

Due to the mistreatment that many wild animals face in captivity, they are often more likely to die before their natural average lifespan. For example, most captive orca deaths can be attributed to opportunistic infections and diseases, meaning the pathogens would normally be harmless but caused fatal diseases because of the unhealthy conditions that the whales were living in. As a result, over 160 captive orcas have died prematurely,203 and 85% of SeaWorld’s female orcas have died before age 25, which is just half the lifespan for wild female orcas.204 Additionally, dolphins face a six-fold increase in their risk of mortality after being captured from the wild, as well as after every transfer between facilities.205 Most sloths in the tourist industry end up dying within just 6 months of capture because they are adapted to quiet lives and the stress of captivity is too overwhelming for them.206

Instances of animal infant mortality are also much higher in captivity than in the wild. Research finds that the infant mortality rate for captive animals is as high as 65%,207 and this rate is especially high for elephants, cetaceansMarine mammals such as whales and dolphins.1, and great apes.208 Although some species demonstrate high infant mortality rates in the wild as well, these rates should not be reflected in captivity where there are no predators and where the animals receive first-class veterinary care. High mortality rates in captivity, then, are partly attributable to maternal neglect as previously mentioned (or even infanticide),209, 210 but researchers have also found that captive conditions are often simply too alien and artificial for infants to thrive. The artificial social grouping, lack of social networks for the mother and infant, and constant presence of humans handling the infants is unnatural and alarming for the mother and infant and can lead to trauma and infant death.211

Many captive animals also die early due to health issues that are a byproduct of inbreeding depressionWhen a population’s ability to survive and reproduce is decreased due to frequent mating between relatives.13. Inbreeding is a common practice in captivity due to the small populations of certain species, and this inbreeding reduces the chances of survival of the offspring because it results in unhealthy genetic mutations and a lack of healthy genetic diversity. One study found that inbreeding depression had a significant effect on neonatal survival in over 119 captive populations of mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians.212 Another study demonstrated that in 15 out of the 16 captive primate colonies that the researchers observed, infant mortality was higher among the inbred primates than the non-inbred.213 Thus, inbreeding is a form of captive animal mistreatment that can lead to premature death.

Occasionally, zoos will euthanize healthy captive animals simply because they do not have the resources or space to continue to care for the animal, or because it would be more profitable for them to use that space and those resources to keep an animal that is more “useful” to them (i.e. it can breed or belongs to a species that is more popular with the public).214 This practice is referred to as “zoothanasiaThe practice of killing a healthy captive animal because the management of the establishment has defined the animal as “surplus” or “unneeded.”21.”215 Most reports of zoothanasia come from European zoos, with an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 healthy animals put down each year across Europe.216 Although inaccurate record-keeping makes it difficult to know the extent to which this occurs in the United States, there have been reports of it occurring.217

Captive animals may also face premature death if they are killed by zookeepers in an attempt to save a human. Accredited zoos have protocols in place for handling animals that threaten the safety of staff or visitors when they act out aggressively; often, these protocols involve the use of lethal force to kill the animal if it is deemed the only way to save the life of the human. For example, in the infamous 2016 case of the gorilla Harambe at the Cincinnati Zoo, workers fatally shot Harambe to save the toddler who had fallen into the enclosure. As Ed Hansen, CEO of AZAAmerican Zoo and Aquarium Association; a federal body that sets voluntary standards for animal care in zoos and aquariums and accredits organizations if they meet the credentials.6, said, “Unfortunately for the gorilla, the only really positive way to ensure the safety of the child was to dispatch the lethal force.”218 Harambe’s case was not an isolated incident; since 1990, 42 animals in AZA-accredited zoos have died during escapes or attacks.219 Taking animals into captivity and then creating protocols to protect the humans who come to see them often results in premature deaths for the animals.

Human Injuries and Deaths

Coupled with the negative consequences of animal mistreatment on animals is the harm that can come to humans who are in proximity with these animals. A 2008 survey by the Marine Mammal Commision found that more than half of marine mammal workers had been injured by the animals, and more than a third of these injuries were classified as severe (such as deep wounds and fractures).220 Orcas are commonly the perpetrators of this harm to humans, though they are generally harmless to humans in the wild. There are a total of only 6 recorded instances of orca aggression toward humans in the wild, and only 1 that resulted in a human injury.221, 222 Captive orcas, however, have been responsible for hundreds of attacks and a total of four human deaths.223, 224 Researchers have dubbed these aggressive attacks as indicators of the animals’ poor psychological health and constant stress and frustration in their captive situations.225 In addition to orcas, there have been approximately 300 people injured by primates being kept as “exotic pets” since 1990.226 In the same time frame, there have been 15 incidents at zoos that have resulted in a human death, and 110 that have resulted in human injury.227, 228 These incidents are evidence that mistreatment of animals has serious consequences for humans as well as the animals.

Practices

Environmental Enrichment

Many captive establishments, especially zoos and aquariums, provide animals with environmental enrichment“An animal husbandry principle that seeks to enhance the quality of captive animal care by providing the environmental stimuli necessary for optimal psychological and physiological well-being.’’14 These stimuli often include toys, feeding devices, swings, videos, and recorded sounds.15 devices in order to help decrease boredom and stress, thus decreasing stereotypic behavior“Repetitive behaviors induced by frustration, repeated attempts to cope, and/or CNS dysfunction.” These behaviors have no apparent goal or function, and are uncommon in non-captive wild animals.9 and increasing psychological well-being. Examples of enrichment devices include toys, feeding devices, swings, videos, and recorded sounds.229 Although there is evidence that these devices can help reduce stereotypic behavior to some degree and are certainly better than barren enclosures,230 other studies show that many animals ignore the devices or do not engage with them in meaningful ways.231 One study among primates found that many of them stop using the device after a few days or even a few hours, and that stereotypic behaviors were rarely reduced when they had access to enrichment devices.232

Additionally, practices such as diversifying feeding schedules to make the animals’ routine less predictable has been shown to decrease stereotypies“Repetitive behaviors induced by frustration, repeated attempts to cope, and/or CNS dysfunction.” These behaviors have no apparent goal or function, and are uncommon in non-captive wild animals.9 in some animals, though it cannot solve the issue altogether.233 This indicates that even the best captive establishments that take great strides to help animals thrive psychologically cannot account for all of the needs of wild animals.

Captive Release Programs

Even in accredited captive facilities, wild animals still often fail to thrive due to the limiting and artificial conditions to which they are not adapted.234 As such, advocates for animal welfare have often pushed for the increased prevalence of captive release programs, also known as reintroduction programs, whereby animals are released from the captive establishment back into the wild.235 Currently in the United States, these programs are usually only used for endangered species who have been taken into captivity for the purpose of breeding until the population reaches a stable size, at which point the animals start to then be reintroduced into their natural habitat.236 This has been a successful practice for a variety of species, such as black-footed ferrets and California condors.237

However, there are significant limitations to this practice as a sustainable way to free all wild animals from the mistreatment of captivity. First, these reintroduction programs have rarely been used for animals that are not endangered and were not cared for and bred with the intention of re-releasing them.238 This suggests that the animals who were not bred and cared for for this specific purpose—which is the vast majority of captive animals—may not be able to successfully survive in the wild. Evidence shows that inbreeds cannot survive in the wild, so all the inbred animals living in captivity would not be able to be released.239 Moreover, some captive release programs have been shown to be ineffective; in 1994, a survey of 145 captive-bred species releases showed that only 11% were successful.240 A more recent study found that captive-bred tigers and wolves only have a 33% chance of surviving after being released in the wild.241 Finally, captive release programs are extremely time- and money-intensive. Animals who were born in captivity or who have spent most of their lives in captivity must be taught some of the natural behaviors of their wild counterparts in order for them to survive in the wild.242 See the box to the side for an example.

Animal Sanctuaries

A more sustainable solution to free a greater number of animals from the mistreatment of captivity is placing animals in sanctuaries. These sanctuaries are for the purpose of animal rehabilitation—a place where animals are not used for entertainment but instead allowed to live in wild-like conditions since they cannot yet survive in the wild. Authentic animal sanctuaries do not force animals to engage in any sort of performance or display, do not allow visitors to interact closely with the animals, do not allow breeding, and have the well-being of the animals as the highest priority. Visitors are allowed to tour the establishment, and these visitors help to offset the cost of the sanctuary, but must keep a respectful distance from the animals.243, 244

It is important to note that animal sanctuaries are still a form of captivity. The animals are kept inside a limited space by gates, walls, or nets; however, this is for the purpose of being able to provide food and veterinary care for the animal, and because these animals have not been trained to survive in the wild. Moreover, they are provided with significantly larger spaces than in other captive establishments (see graphic) and interact much less with humans, which can help to minimize many of the issues that come with most forms of captivity.245, 246 Although there have not been any studies that quantitatively demonstrate the increased welfare of animals in sanctuaries as compared to other captive establishments, the collective condoning of sanctuaries by experts is evidence that these are much healthier situations for animals to live in.247, 248

Additionally, some establishments will call themselves animal sanctuaries while still offering human-animal interaction opportunities or perpetuating other forms of animal mistreatment.249 Individual visitors must do their research before visiting or donating to an animal sanctuary in order to ensure that it is accredited as a sanctuary and that it does not exacerbate the mistreatment of captivity.250

Preferred Citation: Coleman, Madison. “Mistreatment of Wild Animals in Captivity” Ballard Brief. April 2021. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints