Sex Trafficking of Youth in the United States

By Rachel Brown

Published Fall 2021

Special thanks to Jamie LeSueur for editing and research contributions

Summary+

Sex trafficking is a growing yet inconspicious issue in the United States, and youth are especially vulnerable to exploitation. Commercial sexual exploitation entails forcing or coercing a person into engaging in sexual acts for the profit of those who run the industry (i.e., the traffickers). This industry is driven by a demand for child sex and fueled by its lucrative nature. Along with the inherent vulnerability of being young and not yet fully developed, youth have a variety of risk factors which make them especially susceptible to victimization, including experience with child abuse, homelessness, and online exposure. Children and adolescents who are targeted and sexually exploited can suffer damaging short- and long-term physical and sexual trauma to their bodies, as well as adverse mental and emotional trauma that can make it difficult to cope with the maltreatment they have been subjected to. Although trafficking of youth is a multifaceted issue, organizations such as Love146 and the National Human Trafficking Hotline are working to combat specific aspects of child sex trafficking by employing practices that address the prevention and identification of trafficking in the United States.

Key Takeaways+

Key Terms+

Sex trafficking—“A form of modern-day slavery in which individuals perform commercial sex through the use of force, fraud, or coercion.”1

Youth—Minors under the age of 18.2

Victim—An individual currently experiencing trafficking.3

Survivor—An individual in the process of recovering from the trauma of trafficking.4

Trafficker/Pimp—“A person who controls and financially benefits from the commercial sexual exploitation of another person.”5

Survival sex—Engaging in sexual intercourse to secure basic human needs (e.g., food, clothing, or shelter).6

Grooming—“A preparatory process in which a predator gradually gains a person’s trust with the intent to exploit them.”7

Seasoning—“A combination of psychological manipulation, intimidation, gang rape, sodomy, beatings, deprivation of food or sleep, isolation from friends or family and other sources of support, and threatening or holding hostage of a victim’s children. Seasoning is designed to break down a victim’s resistance and ensure compliance.”8

Hematoma—“A collection of blood outside of blood vessels. Most commonly, hematomas are caused by an injury to the wall of a blood vessel, prompting blood to seep out of the blood vessel into the surrounding tissues.”9

Therapeutic abortion—An abortion that is brought about intentionally.10

Context

Human trafficking is defined as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring, or receipt of people through force, fraud or deception, with the aim of exploiting them for profit.”11 Human trafficking is a rapidly growing, highly profitable criminal industry, second only in lucrativeness to drug trafficking.12 There are several different forms of human trafficking; one of the most prevalent in the United States is sex trafficking, which is characterized by the exploitation of a person for sexual services. Perpetrators of the crime are known as sex traffickers—people who coerce their victims into commiting commercial sexual acts in order to earn profits.

Source: “The Traffickers.” National Human Trafficking Hotline, September 26, 2014. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/what-human-trafficking/human-trafficking/traffickers. Swaner, Rachel, Melissa Labriola, Michael Rempel, Allyson Walker, and Joseph Spadafore. "Youth involvement in the sex trade: A national study." (2016).

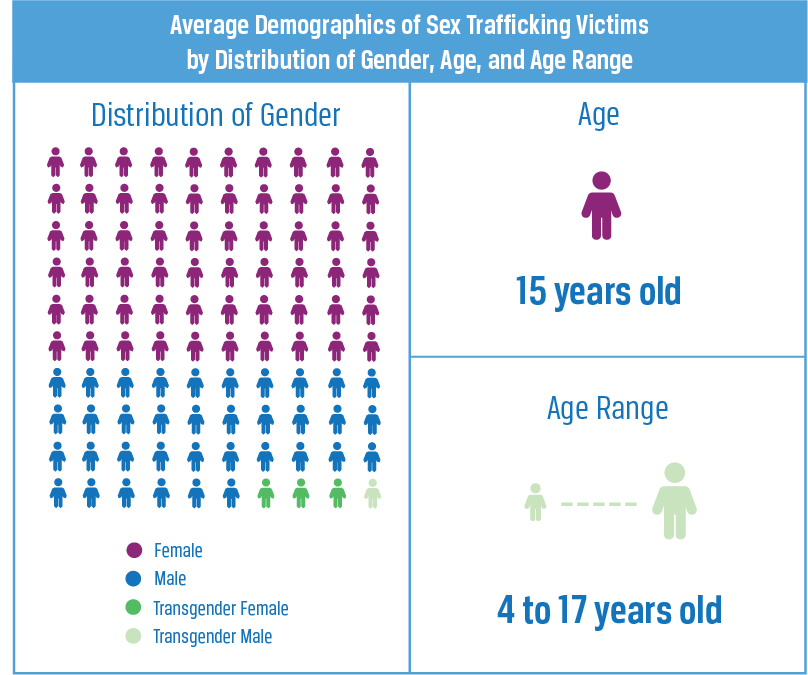

Although sex trafficking victims include both children and adults, children are among the most vulnerable populations in the United States, making them ideal targets for traffickers.13 One study involving 941 victims determined the average age of first exploitation to be approximately 15 years old, with ages ranging from 4 to 17.14 Although the commercial sex industry is predominantly skewed towards the victimization of women and girls, men and boys are also exploited. In a study that interviewed nearly 1000 sex trade–involved youth in 6 areas of the US, 60% of participants were girls, 36% were boys, 4% were transgender females, and less than 1% were transgender males.15 Due to the inconspicuous nature of the problem itself, coupled with a lack of large-scale studies and data, it is difficult to estimate the number of youth in the United States who are at risk or who are currently being exploited in the commercial sex industry. However, most existing estimates place this number in the hundreds of thousands.16 Because children are not yet fully developed emotionally, physically, and mentally, they are easier to manipulate and deceive, and their innate vulnerability is exacerbated by other circumstances that can increase children’s chances of being targeted and persuaded to enter the commercial sex industry. Furthermore, many children who enter the industry during childhood will continue to participate in commercial sex throughout adolescence and adulthood.17

It is widely perceived that child sex trafficking is primarily initiated through kidnapping and transporting to different states or countries. This assumption is not the most common narrative of trafficking in the United States.18 A study analyzing 115 cases of child sex trafficking over a nine year period (2000 to 2009) involving 153 minor victims found that less than 10% of these cases were facilitated through kidnapping.19 In most cases, minors become victimized through processes of targeting, grooming, and recruitment within their own community and sometimes within their own family. Traffickers form relationships with victims and earn their trust through various means, including buying them gifts, posing as a caring confidant (as a friend or romantic partner), or making false promises such as the promise of a career in modeling or similar opportunity.20 Traffickers themselves can work as an individual or operate within a network of traffickers, all with the common goal of gaining profit. Perpetrators can be male or female. A cross-sectional study analyzing 1,416 child sex traffickers arrested in the United States between 2010 and 2015 found that the average age of female traffickers was 26.34 and the average age of male traffickers was 29.2 years.21, 22 The same study identified that 75.4% of the traffickers were male and, of those whose race was identified (731), 71.7% were African American, 20.5% were Caucasian, 3.7% were Hispanic, and the remaining classified as Pacific Islander/Asian and other.23

The geographical scope of child sex trafficking in the United States is difficult to accurately present due to lack of reliable data and research; despite this lack, there have been cases of child sex trafficking found in all 50 states.24 According to the National Human Trafficking Hotline, an organization that receives tips about sex and labor trafficking, in 2019 the most reported cases of human trafficking came from the highest populated states: California (1507), Texas (1080), Florida (896), and New York (454), with the vast majority of these cases being sex trafficking (8,248 of 11,500 cases).25 This find demonstrates that higher populations lead to an increased number of consumers, thereby illustrating that child sex trafficking is driven by demand and is not a geography-specific crime.26 Worldwide, there are many reported cases of child sex trafficking in Central America, the Caribbean, and East Asia; however, statistics on the distribution of child sex trafficking throughout the world are skewed, since in many higher income countries the crime goes undetected.27

The turn of the century brought the first law specifically enacted to combat human trafficking, including sexual exploitation of children, known as the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA).28 Prior to enactment of the TVPA, US laws did not comprehensively prosecute traffickers and protect victims.29 The TVPA buoyed the US government’s ability to prosecute traffickers by expanding the definitions of human and sex trafficking, deeming attempts to participate in such operations illegal, mandating restitution for victims (paid by convicted traffickers), and increasing penalties for violations of existing trafficking laws.30 Cases of sex trafficking from 2010 to 2015 showed that, upon being charged with an average of 3.8 crimes, sex trafficker’s average prison sentence was 13.5 years.31 In addition to increasing prosecution efforts, the TVPA also addresses prevention and protection, allowing for the establishment of more prevention initiatives and efforts (both domestically and internationally) and providing increased services for victims, including foreign victims.32, 33 Since its initial ratification in 2000, the TVPA has undergone 4 subsequent reauthorizations (2003, 2005, 2008, 2013, and 2018), each working to further hinder and indict traffickers and increase protection of victims.34

Contributing Factors

Demand for Child Sex

In accordance with basic economic principles, at the root of the existence of the commercial child sex industry is the demand for the market.35 Child sex trafficking continues to be a profitable venture due to the buyers who solicit sexual acts from underage victims, either directly or through third-party suppliers (i.e., the traffickers).36 Buyers come from a variety of different backgrounds and walks of life, and, although the demographic primarily constitutes men, both men and women have been found to be consumers.37, 38 As an expanding number of consumers fuel the demand, traffickers respond by increasing “supply,” thus enslaving more children in the industry. As a result of the increased demand and consequent increase in supply, traffickers are able to charge less per child or per service, thereby making it easier for buyers to participate in the industry. This process is how the cycle persists and the commercial sex industry continues to grow.39

Source: Erika R. George; Scarlet R. Smith, "In Good Company: How Corporate Social Responsibility Can Protect Rights and Aid Efforts to End Child Sex Trafficking and Modern Slavery," New York University Journal of International Law and Politics 46, no. 1 (Fall 2013): 55-114

Data also suggests that there is a demand for sex with minors. Research conducted in Atlanta, Georgia illustrated this through a survey of 218 men who were responding to online advertisements for commercial sex. The survey gave the interested parties 3 alerts which indicated that the females being advertised were minors, and the results showed that 47% of the men wished to follow through with the transaction despite the information given regarding the age of the girls.40 This research also found that in Georgia 7,200 men engage in 8,700 commercial sex acts with underage girls each month, and among this group, 10% have the specific intent of doing so with girls who are minors.41 Although national research on this subject is lacking, the demand assessed through this study in Georgia provides an idea of the nature of demand for child sex throughout the country.42

High Profit for Traffickers

The high profits available to sex traffickers compel active perpetrators to continue trafficking and entice new traffickers to enter the industry. As previously mentioned, human trafficking is an industry which operates upon the principles of supply and demand; the demand drives the profit. According to the International Labor Office (ILO), the global annual revenue for child trafficking and forced labor in 2012 was approximately $39 billion, and sexual exploitation specifically accounted for approximately 22% of this amount.43 Two years later, the ILO released an updated estimation of the global annual revenue at $150 billion, with $99 billion coming from commercial sex trafficking.44 For comparison, the 2018 global annual revenue for the video game industry was $131 billion.45 The original underestimation and updated information conveys the inconspicuous nature of sex trafficking and the difficulty in assessing the true economic scope of the industry.

One reason for the extremely high profit margins for the commercial sex industry was described by Rebecca Posey, regional director of Not for Sale (a nonprofit aimed at combatting modern day slavery and exploitation), at the Global Peace Convention in 2012: “You can sell a bag of drugs once, but you can sell a person multiple times.”46 This fact is one of the main factors that influences high profitability for child sex traffickers; once they have at least one child to exploit, they have a “product” that provides seemingly limitless transactions and opportunity for financial gain.47

Risk Factors for Victims

Child Abuse

Child abuse is a leading risk factor of sex trafficking for multiple reasons. In the United States, almost 700,000 children are abused each year.48 This number includes physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, and other forms of abuse. In a sample of young people who had been sex trafficked, 65% reported a history of physical abuse, 82% experienced emotional abuse, and approximately half of them reported victimization through some kind of sexual abuse.49 Abuse experienced by a child in the home can also escalate to sexual exploitation at the hand of a parent or other family member.50 A study found that 60% of all minor victims were found to be related to their trafficker, demonstrating the significance of familial trafficking as an excessive form of child abuse. The same study, which assessed risk factors of male child sex trafficking victims, found that compromised parenting and unstable homes had a significant impact on the vulnerability of the child.51 In a separate study specifically researching cases of familial trafficking, the mother was found to be the primary trafficker in 64.5% of the cases, the father in 32.3%, and another family member in the remaining 3.2% of cases. Furthermore, in 100% of cases the child and trafficker lived under the same roof, and the familial trafficking was typically found to be drug motivated.52 Thus, research reveals a correlation between child abuse in the home and child sex trafficking.

Child abuse is also a risk factor for sex trafficking because of the physical and psycological consequences that come from the abuse. Both the short- and long-term negative effects of child abuse can lead minors into the hands of those who would take advantage of their physical and psychological vulnerability, thus placing them in a cycle of victimization.53 This is especially true for children whose abusive situations drive them to the streets as they seek safety from their abusers, often thinking that “street life” could offer some kind of refuge or relief.54

Homelessness

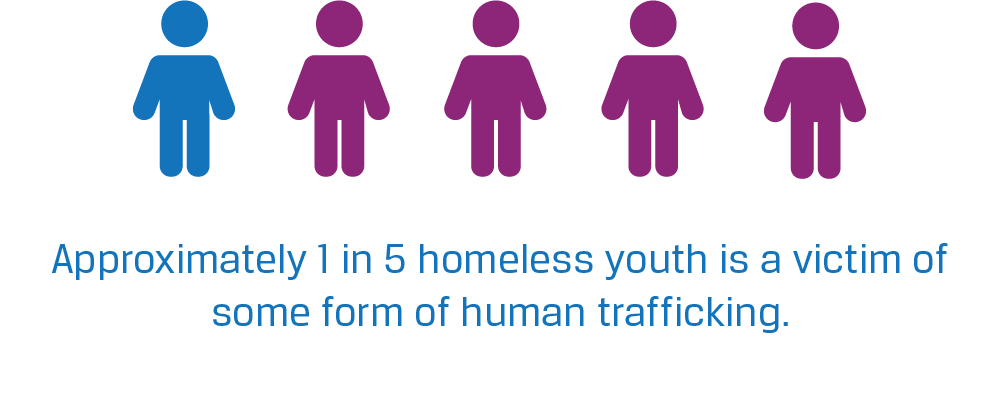

Homelessness is a major risk factor for sex trafficking of youth. In the United States, it is estimated that over 3 million youth experience a period of homelessness each year, and data shows that approximately 1 in 5 homeless youth are a victim of some form of human trafficking.,55, 56 Research done on homeless youth in Philadelphia, Washington DC, and Phoenix indicated that 17% of those surveyed had experienced sex trafficking, and 41% of those who had been trafficked reported being targeted on their first night of homelessness.57 This risk factor is one of the main pathways that leads children and teenagers into the commercial sex industry, making homeless and runaway youth one of the main groups researched in relation to sex trafficking risk factors.58 Part of this risk can be attributed to the fact that lack of a home physically exposes youth to the dangers of “street life,” which includes sex traffickers themselves.59 Pimps can easily prey upon young, homeless individuals because the absence of a permanent residence, adult care, and supervision leaves them physically and emotionally exposed.60 Youth are also at greater risk of being exposed to dangerous situations and individuals who could manipulate and exploit them when they participate in survival sex, which involves engaging in sexual acts purely out of desperation to provide for basic needs such as food, shelter, and clothing.61, 62 Homeless youth are vulnerable, desperate, and more easily taken advantage of, making them conspicuous targets to those who wish to exploit them.

Source: “Human Trafficking.” National Network for Youth. Accessed July 7, 2021. https://nn4youth.org/learn/human-trafficking/.

Online Exposure

Internet use is an avenue that can expose youth to the grooming techniques of sex traffickers. There is evidence that social media is used by sex traffickers to select and groom minors for commercial sex trafficking, and research indicates that this method typically targets victims who are 15 or younger.63 A case study from 2015 to 2017 analyzed victims targeted through social media; the study found that of 845 victims, 250 were recruited on Facebook, 120 on a dating site, 78 on Instagram, and 489 on other types of Internet platforms.64 Thus, participation on social media platforms like those mentioned in the study, as well as Snapchat, Twitter, Kik, Meetme.com, WhatsApp, and more, can expose youth to the victimizing tactics of traffickers.65 The ability to connect with anyone and maintain anonymity through such websites and applications is what allows minors to come in contact with these sex traffickers.66 Traffickers were found to utilize youth’s published personal information on social media sites to identify those who would be most vulnerable to their grooming and recruitment techniques and subsequent exploitation.67 One study evaluated the elements of internet technology used in trafficking and outlined a perpetrator’s strategy as explained in a court case; the trafficker manipulated victims through the use of two fake internet profiles—one for sending abusive messages and one for providing comfort and understanding. This method allowed the trafficker to easily build a relationship with the young people he was targeting.68

The Internet as a Marketplace

Beyond the targeting, contacting, and forming of relationships between minors and sex traffickers, the Internet is also used within the sex trafficking industry to advertise and to complete transactions. Among the most common markets utilized for advertising of victims are Backpage, Craigslist, Myspace, and Facebook.69 Because of the increased access minors have to the Internet, more recent instances of trafficking have involved traffickers advertising the minor on the previously mentioned platforms, as well as traffickers forcing their victims to post their own ads, sometimes several times a day.70 A survey of survivors showed that 26% of them suffered exploitation at the hand of their trafficker through their own personal social media accounts.71 Internet use on behalf of traffickers also includes employing online currency services that conceal commercial sex transactions, making it easier for them to continue to carry out sexual exploitation of young people.72 According to data collected by Chainanalysis, a company that analyzes cryptocurrency databases, the amount of cryptocurrency (specifically Bitcoin and Ethereum) involved in transactions related to child sexual abuse was approximately $930,000 in 2019, which represents a nearly 300% increase since 2017.73 Although this staggering leap is largely attributed to increased utilization of cryptocurrencies rather than rapid increase in demand, it is evident that the Internet is an important factor in the perpetuation of the child commercial sex industry, in relation to both advertising and carrying out transactions in an inconspicuous manner.74

The Internet is also the vehicle for the rapidly growing online industry of child pornography, which fuels the sexualization of children in today’s society and thereby contributes to demand for child sex trafficking.75 The extensive online child pornography market allows traffickers to advertise sexual services and to advertise the children themselves for sexual exploitation.76 Analysis of Google and Dogpile data has shown that the frequency of child pornography-related searches is approximately one out of every 200 to 500 searches.77 Statistics from 2004 to 2013 show that 72% of all federal prosecution cases of commercial sexual exploitation of children were for possessing and circulating child pornography, 18% were for child sex trafficking, and 10% were for the production of child pornography.78 The Internet has made child pornography more accessible than ever, and child pornography is a driving force behind the continual and rapid growth of the child sex trafficking industry, including its influence in leading people to participate in the industry as consumers (increasing demand) as well as leading pimps and traffickers to further exploit their victims through production of pornography.79, 80 Pornography has also been found to be utilized by pimps and traffickers as a grooming and “teaching” tool to prepare child victims for sexual acts.81

Negative Consequences

Physical Trauma

Due to the loss of autonomy that youth experience with sex trafficking as well as the increased probability of experiencing sex-related violence in the sex industry, sexually exploited children are at risk for a variety of physical injuries and conditions.82 Physical injuries include those caused by general violence like bruises, abrasions, and scratches, as well as more serious injuries including hematomas and skeletal fractures. It is evident that physical consequences that children suffer when sexually exploited are consistent with those seen in victims of beating and rape.83 Sexual and physical violence can be initiated by clients, in addition to the violence frequently inflicted by traffickers.84 Pimp violence is typically used as a seasoning technique to increase victim compliance. For example, some victims who are under the control of pimps are expected to meet a certain “quota” each night (often falling between $300 and $2000), and failure to do so can result in harsh beating and the expectation that they will go back out to reach the quota imposed by their trafficker.85 Other health conditions experienced by victims include chronic pain (headaches, pelvic and abdominal pain) and even asthma.86 It is also common to see weight loss due to malnourishment in victims of commercial sex trading. A study done by interviewing 107 adolescent and adult female sex trafficking survivors found that 43% of them had suffered significant weight loss during their exploitation.87 This weight loss is because traffickers will often withhold food in order to coerce victims and compel them to be compliant—starvation being one of the other seasoning techniques utilized by traffickers.88, 89

Sexual Trauma

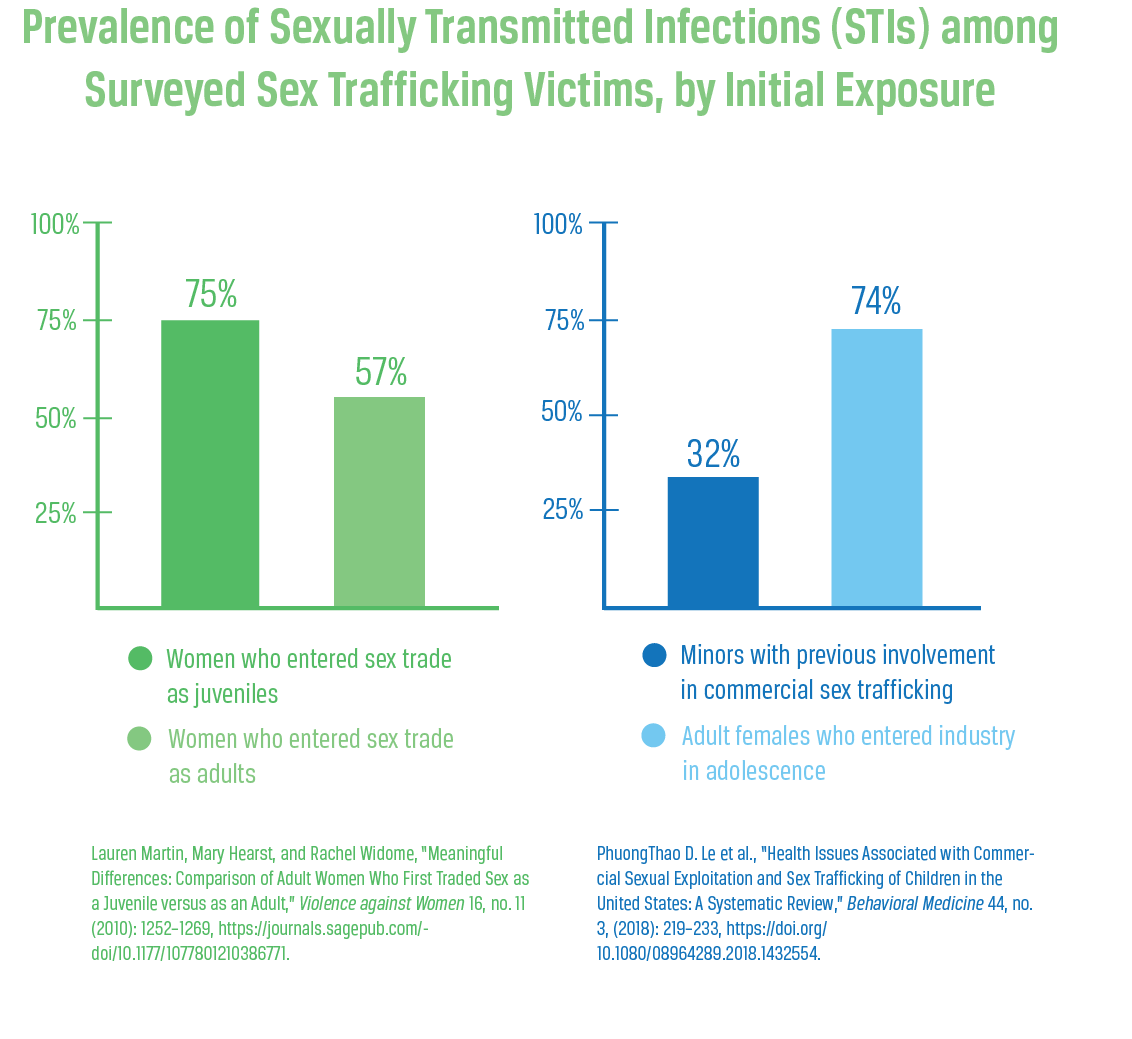

Studies have shown that those who are forced or deceived into some kind of sex work before adulthood will exhibit poorer sexual health outcomes compared to those who are exploited at an older age.90 Such poor health outcomes include sexually transmitted infections (STIs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia), pelvic inflammatory disease, and HIV/AIDS.91 STIs are especially more prevalent in children who are part of the commercial sex trafficking industry versus adults because, anatomically, they are not yet sexually mature. A survey of sex-trading women in Minneapolis found that women who became part of the sex trade as juveniles had higher rates of STI history (75%) versus women who began trading sex as adults (57%).92 Another study showed incidence of STIs in 32% of minors who had previously been involved in commercial sex trafficking and in 74% of adult females who first became part of the industry during their adolescence.93 Other factors that determine transmission of STIs include the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the geographic location the trafficking is taking place (for example, the South is disproportionately affected by new diagnoses of HIV) and the use of contraceptives.94, 95 Studies regarding contraception use interviewed commercially sexually exploited girls and found that, because of the control imposed on them by their trafficker, they were often not allowed to use condoms or felt unsafe trying to use them (safety was also a concern in relation to potential sexual violence from clients).96 Some also expressed that it was “not a priority” since they were more worried about surviving than preserving their reproductive health and preventing pregnancy.97

Pregnancy and Abortion

Girls who are victimized through the commercial sex industry are also at risk for unplanned pregnancies and abortions.98 A study measuring the pregnancy rates and outcomes of 360 girls exposed to commercial sexual exploitation found that 31% reported ever being pregnant, and, among those girls, 18% had experienced more than one pregnancy.99 Of the 130 reported pregnancies, it was revealed that 76% resulted in live births, 13% were terminated through therapeutic abortions, 5% had an outcome of miscarriage or still birth, and 6% were current pregnancies.100 Compared to the US national teen pregnancy birth rate of 2 live births per 100 adolescent girls (as of 2020), this study reporting 99 live births out of 360 girls suggests that the teen birth rate among girls impacted by sex trafficking far surpasses the national rate.101 Another study of adolescent girls who had experience with prostitution and/or survival sex found a high incidence of maternal and infant complications, with 30% experiencing pregnancy-induced hypertension, 22% having preterm births, 15% undergoing precipitous delivery, and 15% of infants being small for gestational age.102

Mental Health Challenges

Negative psychological conditions are some of the main repercussions that plague youth who have been exploited through sex trafficking (while also being a contributing factor, thus leading to potential cycles of victimization). These typically are not transitory consequences; rather, poor mental health associated with trauma can persist and torment survivors for years after the trafficking has ended or even throughout their lifetime.103 Such mental health conditions include low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, suicidality, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).104 Furthermore, victims of child sex trafficking have also been identified as being at greater risk of developing a condition called complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). CPTSD includes all the normal aspects of PTSD (reliving the traumatic experience, avoidance, and hyperarousal), in addition to lack of emotional regulation, dissociation, negative self-perception, difficulty in interpersonal relationships, and loss of systems of meaning (e.g., belief system or view of the world).105 Rather than being traced back to a single event, those who develop CPTSD have usually sustained some form of long-term trauma, over months or years, which explains why it is common among survivors of commercial sexual exploitation.106 Individuals who have been victimized through sex trafficking may feel that they are at fault, leading to unwarranted humiliation and self-disgust, and these intense feelings of guilt can prevent them from disclosing their experiences to those who can help them.107 Concerning the way traffickers’ actions can affect victims, the US Department of State explained that as a result of the dehumanization and objectification traffickers inflict, the “victims’ innate sense of power, visibility, and dignity often become obscured” and “victims can lose their sense of identity and security.”108

The resulting poor mental health that victims can experience as a result of their exploitation can also lead to increased rates of harmful behaviors, including suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts.109 A study assessing certain outcomes of 62 sexually exploited runaway youth found that “most” of them reported self-harming through cutting or burning, 75% reported suicidal ideation, and 57% of the males and 47% of the females reported attempting suicide in the past year.110 Comparatively, nationwide statistics from a school-based survey (grades 9 to 12) found that 18.8% of students reported serious consideration of attempting suicide, 15.7% of students reported devising a plan of how they would attempt suicide, and 2.5% of students had attempted suicide and subsequently required medical attention.111 When considering these statistics, it is important to note that many youth involved in commercial sexual exploitation experienced mental health challenges, including suicidal thoughts and attempts, prior to being trafficked, implying that the elevated statistics for sex trafficking victims are not solely a result of the trauma from their victimization in the sex industry.112 Although it is difficult to gauge the extent to which negative mental health outcomes are a direct result of sex trafficking, it is clear that sex trafficking victims are more likely to suffer mental health problems.

Substance Abuse Disorders

Survivors also exhibit a higher probability of suffering from substance abuse disorders as they attempt to find alternate methods of coping with the trauma they have experienced.113 In a study conducted using data from a Los Angeles juvenile court specifically for children involved in the commercial sex industry, of 364 youth, 88% reported substance use, with the most common substances being marijuana (87%), alcohol (54%), and methamphetamine (33%).114 The same study concluded that youth with previous involvement in commercial sexual exploitation who had been diagnosed with a general mood disorder as a result of their victimization exhibited a probability of reporting substance abuse 5 times greater than their counterparts lacking the diagnosis of a general mood disorder.115 One of the many dangers of substance abuse as a coping mechanism is that drug and substance abuse has also been identified as a risk factor for sex trafficking.Thus, this form of “self-medication” has the potential to lead victims back to the exploitation they once escaped, especially within 2 years of the original trafficking, seeing that some research suggests that youth are more vulnerable to revictimization within 2 years after their period of exploitation.116, 117

Source: Bath, Eraka, Elizabeth Barnert, Sarah Godoy, Ivy Hammond, Sangeeta Mondals, David Farabee, and Christine Grella. "Substance use, mental health, and child welfare profiles of juvenile justice-involved commercially sexually exploited youth." Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology30, no. 6 (2020): 389-397

Social Deficits

The experiences that victims of child sex trafficking experience with traffickers and/or clients can cause obstacles to interpersonal communication and relationships due, in large part, to difficulties with trust and attachment.118 Research done with victim service providers found that victims may exhibit one of two relationship deficits: instinctive mistrust of others or excessive attachment to others. Instinctive mistrust and a decreased ability to build and maintain relationships is typically due to past grooming and manipulation by traffickers.119 Furthermore, if the needs of youth who have escaped sex trafficking are not taken seriously, this can reinforce a lack of trust in those who have the power and resources to provide services.120 Conversely, research also shows that other victims readily form attachments to others in an effort to increase their own personal sense of security and comfort.121 Both of these outcomes can have negative social implications for those afflicted, the former potentially leading to social seclusion and the latter placing victims at greater risk of revictimization.122 Some survivors also may feel shame or embarrassment that leads to behaviors of isolation from family as well as difficulty forming new relationships and integrating into various social settings.123, 124, 125 The combination of these factors, coupled with the stigma associated with the sex trafficking industry, can make reintegration into social circles and settings fraught with challenges.

Victims of sex trafficking may experience gaps in or absence of education leading to decreased further education and job opportunities. A study interviewing nearly 1000 homeless youth across 13 US cities found that victims of sex trafficking were 72% more likely to have dropped out of high school than the youth who had not experienced sexual exploitation.126 Of those who reported experiences in the commercial sex industry, only 22% had a high school diploma.127 Because the age range of exploited youth is so broad, with the average age falling in the early teenage years, many victims of exploitation have not had the opportunity to receive a full formal education.128 Furthermore, the physical, mental, and emotional trauma suffered by survivors can greatly impact their future learning experiences, manifesting in educationally harmful behaviors such as anxiety, truancy, learning difficulties, difficulty participating in recovery programs such as those involving job-skills training, and more.129, 130

Practices

US Prevention Education

While the actions of survivor care and apprehending of traffickers are both extremely important in the fight against human trafficking, there is significant value in preventative measures, especially preventative education. Love146, an accredited non-profit organization, teaches a trafficking prevention curriculum called Not a Number to children in the United States and employs other preventative measures in areas of Africa and Asia. The curriculum is typically implemented in schools, child welfare agencies, and other youth organizations that work with at-risk youth, and it can be taught in 4 to 6 hour-long sessions.Their curriculum was developed through working with experts in the fields of human trafficking and sexual exploitation, in addition to extensive research, assessment, and working personally with survivors. As the title Not a Number suggests, the class is based on the idea that no child has a price tag, and the aim of the curriculum is to “provide youth with information and skills in a manner that inspires them to make safe choices.”131 It includes 5 modules designed to give youth the information they need to keep themselves safe: An Introduction to Human Trafficking and Exploitation; Society and Culture; Red Flags and Relationships; Vulnerability and Resilience; and Reducing Risky Behavior and Getting Help. Educating youth about what can make them vulnerable, what behaviors are risky, and what strategies traffickers employ to manipulate young people has the power to empower and equip youth with the tools they need to be aware and protect themselves.

Impact

As of July 2021, 62,326 children have been reached by Love146’s prevention education measures, with 29,698 of those being youth in the United States. This is a 0.14% increase compared to the statistic released in 2020 (62,240 children) and a 19% increase compared to the statistic released in 2019 (52,518 children). Additionally, 1,091 facilitators have been trained and certified to administer the curriculum, and 337 agencies have been licensed with Not a Number as of 2021.132 Often it is difficult to measure the impact of preventative measures like those employed by Love146, but their website attempts to combat this difficulty by providing various testimonials from children whose participation in the program changed their lives and helped them escape trafficking. One such anonymous youth featured on their website shared an experience they had where they “’managed to get away.’” The youth explains, “’I made an excuse and got out of there as fast as I could . . . Because of what we’ve talked about at Not a Number, I paid closer attention and knew to trust my gut . . .’”133 The information they have provided shows that this practice of providing preventative education is continuing to reach youth in the United States.

Gaps

One of the obstacles to the effectiveness of this practice is that it requires that people know of its existence. The curriculum itself is very well organized and based off of the most current research and experiences of survivors themselves; however, with only 337 agencies licensed to teach the curriculum, the organization could work to widen their reach. Another aspect of the practice that could be improved would be to find ways to assess its effectiveness in the lives of those it “reaches.” The Love146 website offers information about how many children the prevention education reaches, but this information only details how many young people have taken the course rather than how many young people utilize or value the prevention education. It could be beneficial to wait a certain amount of time after they have taken the course, and then offer a survey or questionnaire asking specific questions about how or if they feel the curriculum has helped them be more aware and protect themselves. This approach would aid in evaluating the practice based off of responses from those who have experienced the practice first-hand.

National Human Trafficking Hotline

The National Human Trafficking Hotline is a communication platform dedicated to aiding victims and survivors of sex and labor trafficking by connecting them to resources and services to ensure their needs are met and by involving law enforcement when necessary. The hotline features a toll-free phone and SMS text messaging service as well as a live online chat feature, all of which are available every day of the year. While the National Human Trafficking Hotline does not directly provide services to victims and survivors, it connects them with necessary services like anti-trafficking services, local social and legal services, and providers of emergency assistance. In addition to leading those who contact them to the help they need, the hotline also receives and reports tips of potential sex and labor trafficking.134 (Suspected cases of child trafficking are reported to the proper authorities. In cases where danger is not imminent and the law does not require it, action is not taken without the consent of those who contact the hotline.135) The hotline serves any person who seeks help, and it respects victims’ rights to dictate what steps are taken once they begin their process of involvement. The hotline is managed and operated by Polaris, a nonprofit organizaiton dedicated to fighting modern slavery and supporting victims of human trafficking.

Impact

According to the National Human Trafficking Hotline’s 2019 Data Report, there were 22,326 victims and survivors of human trafficking identified, with 14,597 of those being identified as victims of sex trafficking specifically. There were also 4,384 traffickers identified. In addition to measuring the number of individual victims and survivors, the hotline also reports the number of cases, each case representing a “distinct situation” of trafficking that may involve one or more potential victims.136 In 2019, there were 11,500 cases of human trafficking identified (sex trafficking accounting for 8,248 of those), which is the culmination of a steady increase since 2015 when the total number of sex trafficking sitations identified was 5,713. The number of victims and survivors who contact the hotline themselves has also grown steadily and exhibited a 19% increase from 2018 to 2019. In 2013, the hotline diversified its methods of communication by expanding to include texting among its forms of contact, thereby allowing for increased opportunity and accessibility for victims, survivors, and those who provide tips of suspected trafficking situations. The ability to utilize texting is especially significant for underage victims, as illustrated by the 42% of minor victims and survivors who reached out to the hotline via text in 2019 versus the 17% of adult victims and survivors who used texting.

Gaps

In order for the National Human Trafficking Hotline to be an effective platform for receiving tips and aiding victims and survivors, it is important that people are aware of their services and how they can contact them. The hotline does not appear to have an effective way of determining how most of their contacts learn of them, made apparent by insufficient data and poor presentation of data on their website. In 2019, the leading way that people discovered the hotline was through the Internet, and, while this is a way for many individuals to come across the hotline, not everyone has access to the Internet.137 For victims who may not be able to access the Internet, it would be of benefit for the hotline to determine alternative ways of promoting awareness. According to data from 2019, victims are the second most common individuals who contact the hotline, constituting 10,490 contacts out of 48,326, with the most common being community members (13,210 contacts).138 This data suggests that there may be barriers to victim outreach, thus highlighting a potential for more research to be done in order to assess how victims can become aware of and more easily reach the hotline. Furthermore, most (7,749) of the 11,500 trafficking cases in 2019 were identified through the reporting of a trafficking tip, and only 2,918 were identified by requests from victims to access service referrals.139 This finding indicates that the time and energy dedicated by the organization to connecting victims to helpful services and resources may be secondary to the amount dedicated to receiving and following the designated protocol for tips. Although tips are a very important aspect in the efforts against human trafficking, once a tip is reported to the relevant law enforcement or investigative agency, the hotline is no longer directly involved.140 Therefore, it is difficult to assess the direct impact the National Human Trafficking Hotline has in relation to these investigations.

Preferred Citation: Rachel Brown. “Sex Trafficking of Youth in the United States.” Ballard Brief. November 2021. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints