Untreated Mental Illness among Veterans in the United States

By Erin Anderson

Published Fall 2021

Special thanks to Lorin Utsch and Jamie LeSueur for editing and research contributions

Summary+

In the United States, less than half of the veteran population have received screening or diagnosis for mental illness or have received mental health counseling and treatment, resulting in many veterans with severe mental health issues living without a proper diagnosis. Many factors contribute to these statistics, including negative social stigmas surrounding mental health, mistrust of mental health professionals, a lack of publicity and communication about veteran benefits, and limited amount of resources available to treat such a large population. Mental illness at this level impacts not only the quality of life of each veteran but also the livelihood of their families. Studies report that untreated illnesses influence the ever-growing suicide rates, substance use disorder (SUD) reports, and intimate partner violence (IPV) declarations among veterans, their partners, or families. Leading practices for combating this social issue include seamless transitioning from active duty to retirement, with accompanying early screening, diagnosis, and referred treatment.

Key Takeaways+

Key Terms+

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—A psychological reaction occurring after experiencing a highly stressing event (such as wartime combat, physical violence, or a natural disaster) that is usually characterized by depression, anxiety, flashbacks, recurrent nightmares, and avoidance of reminders of the event.1

Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF)—Refer to the US–led conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq. Specifically, OEF refers to the war in Afghanistan, while OIF refers to the Iraq War (October 2001 to December 2014 and March 2003 to November 2011).2

Veterans Administration (VA)—The largest nationwide response organization that is devoted to veterans’ post-service life and health. It is responsible for providing vital services to veterans, including health care services, benefits programs, access and regular maintenance to national cemeteries and dignified burials, and a commitment to refined reaction to potential war, terrorism, or emergency consequences.The VHA (Veterans Health Administration) serves as a specified branch under the VA, and focuses exclusively on veteran health. For the purposes of this brief, the abbreviation “VA” will be used as an overarching term for veteran health, services, and benefits, including the VHA health services available.3

Substance use disorder (SUD)—A disease that affects a person's brain and behavior and leads to an inability to control the use of a legal or illegal drug or medication. Substances such as alcohol, marijuana and nicotine also are considered drugs.4

Opioids—A class of drugs used to reduce pain. Common types are oxycodone (OxyContin), hydrocodone (Vicodin), morphine, and methadone.5

Intimate partner violence (IPV)—Physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse.6

Psychotherapy—A general term for treating mental health problems by talking with a psychiatrist, psychologist, or other mental health provider.7

Psychopathology—Refers to the study of psychological and behavioral dysfunction occurring in mental illness or in social disorganization.8

Context

Q: How many US veterans have untreated mental illness?

A: According to a 2016 study, nearly 1.1 million of a total of 19 million veterans were diagnosed with one of five mental illnesses—depression, PTSD, substance use disorder, anxiety, and schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.9, 10 As new research arises in these fields, investigators note that veterans who test positive for these psychiatric disorders typically have had them for several months, or even years, without the use of therapy or treatment-based resources.11 An example of this is apparent in the lack of outpatient care for OEF-OIF veterans; nearly 43% of this group of veterans have been diagnosed with at least one mental illness, while a follow-up national survey reported that only 25% of this group have sought after outpatient services.12 Other research shows that only 50% of veterans returning home receive any mental health treatment.13 It is important to note with these illnesses that there is a difference between untreated and undiagnosed. Undiagnosed veterans are those who either have not been screened for illness or have not been officially diagnosed by a medical professional. Untreated veterans refer to the population that have received some form of official diagnosis and have not sought out or been accepted into a treatment program or plan.

Q: What mental illnesses do veterans commonly experience?

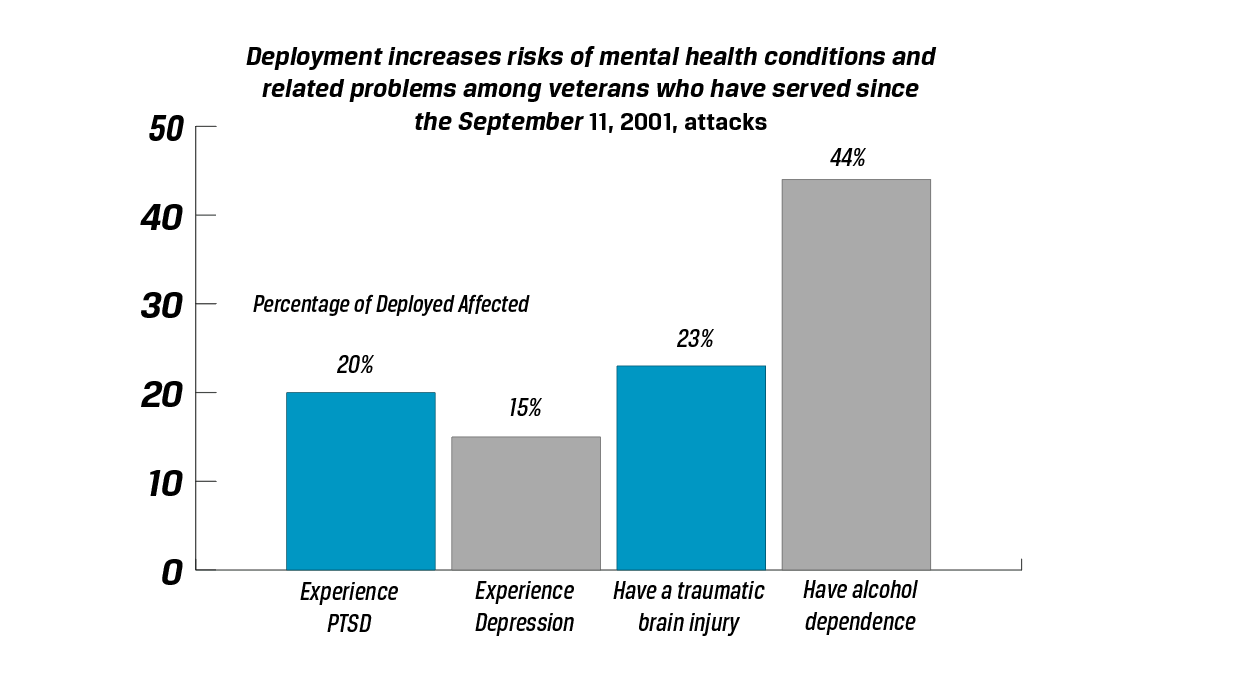

A: Most commonly reported mental illnesses in US veterans often stem from and focus on mood disorders such as depression; psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia; PTSD and other anxiety-based conditions; and substance use disorders, as well as many interrelationships between these types. These mental illnesses all have the potential to escalate into self-harm or suicidal ideation.14 Of these mental issues, 15% experience depression, 20% of veterans who were previously deployed experience PTSD, 23% have some sort of traumatic brain injury that can be a source for mental consequences, and 44% report some kind of alcohol dependence.15 Sampled veterans reported that symptoms of these illnesses often include feeling triggered by things that bring back memories of a traumatic event, having nightmares, vivid memories, or flashbacks, feeling emotionally cut off or numb, having difficulty sleeping, and having trouble concentrating.16, 17 Additionally, veterans express symptoms differently; some tend to exhibit mental illness internally, with acute feelings of sadness or loss, while the majority exhibit mental illness externally, often in forms of addiction or antisocial behaviors.18

Q: Which veteran populations are most likely to develop these illnesses?

A: Veterans who were deployed to a warzone and experienced combat, accounting for 39% of all US veterans, report greater post-war mental health issues than those who served in other capacities.19 In comparing which contemporary American wars leave veterans with greater combative trauma and likeliness to develop mental illness, it was noted that Vietnam veterans typically self-report poorer overall health20 and are about 15% more likely to develop PTSD than OEF, OIF, and Gulf War veterans. 21 A 2018 study determined the frequency of mental illnesses diagnoses from different branches of the military, and found that the Army had the highest number of cases at 17.5%, followed by the Navy with 11.9%, the Marine Corps with 11.7% and the Air Force with 11%. The rate of mental illness diagnoses was also found to be higher among enlisted persons compared to officers.22

Among samples of civilian men and women, there was no difference between psychopathology prevalence in one gender over another.23 This means that both men and women entering the military are equally likely to develop mental illnesses. Nevertheless, there is a gender distinction in the type of illnesses developed: Female veterans are more frequently diagnosed with PTSD and depression-related issues, and male veterans predominately receive substance use disorder (SUD) diagnosis or other compulsive disorder diagnoses.24 Of the female veteran population, young Black veterans are at the greatest risk for developing depression diagnoses. Of the male population, young White veterans are the most likely to develop SUD disorders.25 In addition, veteran population demographics suggest that both male and female veterans that report being divorced, never married, or younger (16 to 29 years) are more at risk to develop mental illness due to lack of social support.26, 27

Interestingly, 58.7% of veterans with post-service mental health conditions had mental illness diagnoses pre-service. Many of these veterans with pre-service conditions report heightened symptoms and effects of their mental illnesses upon return.28, 29 A 2014 interview study found that nearly 1 in 5 soldiers reported having a common mental illness before enlisting in the military.30

Q: What mental health treatment options are afforded to veterans?

A: Veterans can receive healthcare, including mental health treatment, through the US Department of Veteran Affairs. Veterans receive VA benefits for free if their combat-related injuries are substantial enough to render them partially or fully disabled (as scored by the VA on a percentage scale from 0% disabled to 100% disabled), and veterans who do not qualify for free care can pay for VA treatment using private health insurance. A rating of 100% mental illness disability means complete occupational or social impairment.31 Veterans getting VA treatment for mental illness that developed during service will receive more benefits than those being treated for preexisting conditions that worsened during service.32 More than 1.7 million veterans received mental health services through the VA in 2020.33 National data reports that 48% of the total veteran population in the United States have been served on a one-time or repeating basis by some branch of the VA system, and that 19.9% claim the VA as their main source of health care.34, 45 However, about 58% of surveyed veterans seeking help indicated that they would use the VA-accredited resources only if they did not have access to any other health care facility.36 Other resources veterans choose to use through their private health insurance include organizations such as Military OneSource, suidice prevention hotlines, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).37

Q: What populations are most likely to go untreated?

A: Data from a 2019 study suggests that veterans with a history of psychopathology are more likely to use VA services.38 That same study profiles VA users and shows that the veterans who most frequently seek out the VA are Black, younger, female, unmarried, less educated, and have lower household incomes. Veterans seeking treatment from the VA are also more likely to have served longer in combative military positions and report more traumatic experiences.39 Additionally, these veterans were also more likely to meet higher disability rates, and score lower on measures of day-to-day functioning.40 One study found that of veterans who use the VA for healthcare, those with a rating of 100% disability were more likely to use VA health services—including mental health services—as compared to those who scored between 10% to 40% disability. This trend suggests that VA disability ratings are a significant indicator of whether or not a veteran will be treated by the VA.41 Those outside of this profile may be more at risk for untreated illness.

Additionally, a study of the retention capabilities of the VA discovered that early discontinuation of mental health treatment is more common among veterans with PTSD who are of minority race or ethnicity.42 Other research notes that veterans coming from low socioeconomic backgrounds, rural areas, and those that harbor negative personal beliefs about mental health treatment are the least likely to seek out and receive treatment.43

Q: Why are there gaps in the research surrounding untreated mental illness of US veterans?

A: Researchers studying mental health usually rely on individual semi-structured interviews, focus groups, document reviews, participant observation, and research that relies almost exclusively on self-reports and voluntary participation.44 Thus, data on the presence of mental illness in all kinds of populations may be skewed and research is scarce. PTSD and other related mental illnesses were not recognized as diagnosable disorders—and therefore were not treatable or researched—by the VA until 1980.45 Serious observations and interviews on the effects of mental illness began in the early twenty-first century.46 Data is also limited because the United States is exempt from most global veteran reports, based on the given size of its military, the number of conflicts in which it has taken part, its social services, and its overwhelming population of veterans.47

Contributing Factors

Mental Illness Stigmatization

One of the major factors contributing to the prevalence of untreated mental illness among veterans is the historic and deeply rooted social stigma surrounding mental health treatment. Survey data from OEF and OIF veterans reveals that stigmas are felt by veterans and pose barriers to them receiving care, with veterans who test positive for psychiatric disorders and tendencies being twice as likely as veterans who do not screen positive to report these concerns.48 One way mental illness stigmas are created is through written and spoken language that fallaciously categorizes and stereotypes all people with mental illness. This can lead to misconceptions and beliefs about mental illness that alter clinical realities and contribute to rigid stigmas.49 Those who see others with mental illness often assume and perceive that those who have mental illnesses are dangerous, criminal, could be shamed, could be blamed, or are incompetent and lacking discipline.50 These kinds of stigmas result in two different types of social behavior among veterans: severe lack of regular conversations surrounding topics of mental health; or, reported feelings of pride, ignorance, denial, or weakness among veterans refusing care.51, 52

Veteran attitudes and actions toward mental illness are also shaped by a stringent military culture, which promotes a sort of hyper-masculinity paradigm and transcends ethnicity.53 A literature review of military personnel surveys collected from 2001 to 2014 reported that the two most endorsed, self-reported stigma beliefs surrounding mental illness were “My unit leadership might treat me differently” at 44.2 percent, and “I would be seen as weak” at 42.9 percent.54 An older, midwestern veteran further explained how this culture led him to feel ashamed when he couldn’t cope with and solve his PTSD on his own. Dissuaded from receiving proper treatment, he began self-medicating by drinking alcohol excessively for the next 18 years of his life, ultimately leading him to develop a hard-to-break addiction.55 Military culture also classifies soldiers as "combat" or "non-combat", with an accompanying sense of “combat” elitism and hierarchy. This paradigm influences many non-combat veterans to believe they should not seek out care or they are not deserving of care.56 While greater efforts have been made among rising generations to reduce stigmatization, the majority of veterans who suffer often do not acknowledge the issue out of fear of being seen as defective or different.57

Mistrust of Treatment Programs

Many veterans also choose not to receive treatment based on concern surrounding confidence and trust in the programs and systems designed to offer care. In fact, in a study based on determining potential correlations of mistrust in therapeutic programs, 82.5% of diagnosed or at-risk veterans surveyed on the topic of opting into some form of treatment reported a fear of privacy and confidence breaching, or the fear of being disbelieved.58 In a study on this recurrent issue, it was found that among several choice characteristics for a veteran’s ideal counselor, the overwhelming majority preferred a counselor who was also a veteran, or someone who could relate to them.59 Thus, trusting relationships between client and therapist can influence a veteran’s motivation to meet with professionals after service.60 Established relationships between therapist and client may be harmed when transitioning from in-service treatment (with military health care professionals) to post-service treatment (with civilian health care professionals), because of a loss of relatability. Researchers have identified that many veterans believe that treatment may lack proper innovative research or may only provide temporary results.61 For certain minority at-risk veterans who started but then discontinued treatment, the reasons behind discontinuation of treatment were most often related to perceiving their clinicians as not helpful with medication side effects, not caring in demeanor, or the veteran not feeling welcome at VA facilities.62, 63

Barriers to Treatment

Substandard efforts to inform, educate, and support veterans in reaching out to and taking part in accredited healthcare facilities also plays an influential role in the cases of untreated mental illness. In 2018, the US Government Accountability Office found that of the 6.2 million dollars set aside for suicide prevention and mental health media aimed at veteran viewers, less than 1% ($57,000) was actually spent, with the remaining funds to be redistributed from that purpose and reallocated at the end of the year. This was a significantly lower statistic than past expenditures because officials only implemented publicity efforts that were already in place, rather than promoting and financing new ones, suggesting an insufficient amount of advertisement.64

While veterans meet with Department of Defense medical resources during active duty, the complexity and longevity of communicating health records and pertinent information between active duty facilities and those used by veterans after their service in civilian life is enough to discourage continued treatment. The process of transferring medical records is often not explained effectively to discharged servicepeople. Veterans expressed that the difficulty of navigating the instructions for applying and receiving help from various programs available to them, and the fact that program availability changes with veteran service status, is an added barrier to receiving care.65 Among the many challenges associated with returning to civilian life, veterans are also expected to understand eligibility, insurance coverage, and unique exceptions, as well as know which facilities can treat them.66 Of a sample of returned veterans, 66 of 80 selected veterans from both urban and rural areas of the country reported little to no knowledge of the full benefits that their health plans offer or how their involvement in the military ensures or does not ensure their eligibility.67

Other veterans reported their own self-imposed barriers, such as denial to receive treatment based on length of service, military positions, race and culture, or socioeconomic status. In their cases, many believe that these fundamentals disqualify them, when they are in reality still eligible and qualified to receive care.68 Insufficient advertising, vague instructions about accessing treatment, and self-imposed barriers often deter veterans in need. The absence of accessibility and convenience in applying to and following through with mental health treatment greatly influences the number of veterans who remain untreated for mental illness.

Lack of Available Resources within Healthcare Programs

Even if veterans have overcome stigmatization and received information on outreach programs for addressing their mental needs, the amount of available resources within healthcare programs may not be able to support those who have applied, contributing to the cases of untreated mental illness among veterans. Generally speaking, nationwide shortages in medical professionals has contributed to insufficient care for veterans; as fewer individuals pursue clinical schooling, there are not enough institutions to reach certain geographical locations, and the medical professionals that are available must divvy up their schedules to see a large number of patients.69, 70 The VA in particular has reported employing approximately 21,000 mental health employees, with 9,000 licensed as mental health counselors. In 2016, the caseload per each counselor was raised by 50 percent, requiring counselors to see an average of 30-34.5 patients a week, instead of the previously expected load of 20. Recently, 57 counselors, from 45 Vet Centers in 25 states have made remarks that this number is too high, and poses an ethical dilemma in some cases.71

In a review of surveys and commentaries on the workforce and infrastructure of the VA, healthcare professionals signified several factors contributing to a general shortage in providers: widespread national shortages of professionally trained individuals, lengthy and inefficient hiring processes, and high turnover due to excessive workloads healthcare system, paradoxically negatively affecting the mental health of mental health counseling staff. In many cases, 20% of hired clinicians quit within the first two years of being hired, and re-hiring can take anywhere from 60-120 days.72 This implies that the VA must continually dedicate time and resources to find and maintain staff, which takes away from the time and resources that could be spent addressing veteran mental health. Shortage in healthcare providers and overwhelming loads on healthcare facilities, leaving veterans with even more difficulties in obtaining appointments close to their times of submission. Currently, US government officials have not explicitly required community care wait time goals, which has left the average veteran waiting 41.9 days between submitting an application and being seen for an appointment.73 In particular states with higher populations of veterans, visits can potentially be planned months in advance, with little to no flexibility and no guarantee for timeliness.74 This is the case for a seasoned veteran residing in the urban center of Lincoln, Nebraska. After three separate attempts to be seen by local VA facilities for SUD and PTSD-related issues, he did not receive return contact or any opportunity to schedule visits.75

Consequences

Self Harm and Suicide

High suicide rates correlate with untreated mental health among veterans. In a 2015 study on Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, 14% reported a history of self-injury, with an increased scaling towards suicidal ideation and planning.76 According to the Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report, processed and compiled by the VA, nearly 20 veterans commit suicide a day, and nearly three quarters of those are not receiving the most inclusive and primary VA care for mental health treatment.77 In a study conducted on a group of OEF and OIF veterans screened positive for pre-suicidal symptoms or ideation, results indicated that while veterans accepted the need to assess suicide risk, more than half did not honestly report the full extent of their ideations because of shame, privacy, fear of unwanted hospitalization and medication, or offense taken by the types of screening conducted.78 This lack of proper data-gathering and symptom-reporting perpetuates the risk of suicide among veterans with mental illness.

The total number of suicides among service people differs by age group: an average of 69% involve veterans aged 50+, while an average of 39% involve veterans 49 and younger.79 These statistics suggest that a large majority of suicidal veterans in the United States belong to the Vietnam War population because of their general median age group. Recent VA-issued state data sheets also suggest that veterans living in rural western locations in Montana, Utah, Nevada, and New Mexico have higher chances of suicidal ideation, often due to the distance between veterans in remote areas that have to transport farther to reach their preferred VA facility.80 Because of the lack of mental illness assistance for veterans, there is a higher risk of suicide among veteran populations in the United States, comprising 13.5% of the suicide statistics beginning in 2017 to current day.

Substance Use Disorder (SUD)

Another associated implication of veterans not receiving mental health care and treatment is the development of unhealthy coping mechanisms, which may include substance abuse. Substance Use Disorder (SUD) typically includes dependencies on alcohol, or illicit and prescription drugs. These substances act as a provisional replacement for proper medications and therapies especially related to correlational mental illnesses.81 Veterans develop addictions or abuse tendencies to abate physical or potentially chronic injuries, as well as to inhibit mental pains and adverse reactions.82 More than one in ten veterans have been diagnosed with a substance use disorder, slightly higher than the general population, which reports exactly 1 in 10 Americans.83 Veterans, in particular, often form addictions to drugs and substances related to opioids, like prescription medications (painkillers, benzodiazepines, sedatives) and heroin.84 Furthermore, a nationally-representative sample reports that nearly one-third of veterans investigated list not only a current substance use disorder (SUD), but also an increased likelihood of developing lifetime SUD for certain substances – mainly tobacco and alcohol.85

The research fails to determine causation between SUD and mental illness and instead presents just the correlational data. Thus, it’s inconclusive the degree to which untreated mental illness causes SUD compared to SUD causing mental illness; instead, research has indicated that there is a significant relationship between the two. One study also shows that a correlation exists between SUD individuals, veterans, and low mental health, with SUD veterans experiencing the lowest mental health functioning of other veteran populations included.86 When SUD tendencies and addictions do begin with undiagnosed and untreated mental illness, it is primarily through PTSD or depression with associated feelings such as guilt, extreme sadness, or anger. The VA confirms this connection, with an annual report concluding that 1 in every 3 veterans seeking treatment for SUD also have untreated PTSD symptoms that are rated severe.87 Another leading factor for SUD includes exposure to trauma, with several veterans diagnosed with SUD behaviors reporting having experienced interpersonal or public-witness traumas (e.g., history of childhood physical or sexual abuse, or observing trauma first hand).88, 89, 90, 91 While SUDs can be caused by mental health issues, it also continues to contribute to the retrogression of mental health, along with and physical health, work performance, housing status, and social function.92

Mistrust of Treatment Programs

Unresolved mental health also has a lasting impact on home and family life. Intimate partner violence (IPV) commonly includes physical, sexual, or psychological aggression in which one or multiple persons feel uncomfortable or do not consent to the behavior.93 The VA acknowledges that military service has unique psychological, social, and environmental factors that contribute to elevated risk of IPV among active duty service members and veterans.94 While there is correlational significance between PTSD and IPV, veterans with PTSD are not guaranteed to be IPV perpetrators.95 A VA-associated survey reported that 22% of veteran families were experiencing IPV, as a result of their veteran family member perpetrating one or multiple forms of abuse.96 A study on combating military family IPV suggests that untreated mental illness - whether or not it has been diagnosed - increases the risk of violence in the family.97, 98 In a similar study on the prevention of reported IPV, a small group of veterans were selected because of their partner’s IPV reports, and were specified as to whether or not they exhibited signs of PTSD related to their general military service. Of those included in the study, 80% were determined to have PTSD related-symptoms (meaning that they scored higher than 50 points on a self-survey), and were determined to be at “high risk” for continuing IPV perpetration in their relationships as a function of the social and emotional sequelae.99 It was also found that the majority of IPV veteran perpetrators who suffer from PTSD most often apply bi-directional violence, meaning that more than one type of abuse is inflicted.100 An inclusive literature review assembled from reviewed sources found that among both military veterans and current servicemen, intimate partner violence strongly correlates more with veterans than active servicemen and servicewomen, and is most commonly related to symptoms of victim injury, increased or abnormal substance use, depression, and signs of psychiatric dysregulation.101, 102 Brain and personality differences, traumatic psychopathology, and SUD tendencies were listed as a paired prevalent grouping and predictor of IPV occurrences.103

Best Practices

Immediate Treatment and Consistent Follow Up

Immediate treatment involves early screening and diagnosis. A collection of studies suggests that from among the American veteran population those who do not evade screening (by choice or by chance) and receive proper, targeted interventions and diagnoses are better able to sufficiently treat their diagnosis, and in some cases prevent chronic mental illness.104 The VA health services have incorporated postdeployment screening, through the use of the Post Deployment Health Assessment (PDHA) and the Post Deployment Health Reassessment (PDHRA), which involves both mental and physical questionnaires and a face-to-face appointment with a medical provider who determines whether or not to provide referrals based on disability ratings assigned and eligibility for benefits.105 From there, it is decided what benefits and treatments the VA will offer to each individual veteran, active duty personnel, reservist, or guard member.

Immediate treatment plus consistency and follow up provide immense benefits for mentally ill veterans. A study verified that quickly-implemented secondary recovery sources can accelerate treatment processes, eliminate sources and triggers of fear, and consolidate memory and habit building to avoid the onset of other mental illnesses. This study also suggested that PTSD and depressive veterans benefited most from being enrolled rapidly after discharge in different types of secondary intervention, including psychological debriefing, pharmacology resources, and psychosocial interventions.106 Consistent treatment is also critical as shown by one study where after only 5-8 weekly sessions of some sort of behavioral activation, researchers reported a reduction in the veterans’ PTSD and depression-associated symptoms, and the veterans maintained these results in continual 3-month follow ups.107

Yet very few veterans received an adequate dose of psychotherapy following their referrals, from VA professionals, to meet with mental health services. Many mental health treatments, including extensive readjustment-based counseling and therapy sessions, require months, or even years of consistent time commitment and practice, which needs to be monitored and encouraged over time, for each individual patient. In one literature review, it was discovered that longterm EBPs (evidence-based practices) are implemented sparsely and variably. Where EBPs were taking place, it was noted that the VA was mostly reaching populations in which one or more of these factors applied: being white, being female, living less than 30 miles from a facility, having a recent major health event, having three or more medical comorbidities, having greater PTSD symptom severity, having depressive symptoms, having more severe alcohol use disorder comorbid with traumatic brain injury and PTSD, and having low social support.108 This means that veterans not influenced by these factors were not experiencing treatment initiation or adequate retention.

Although the VA offers opportunities for immediate treatment and consistent follow-up, the impact seems to be minimal and poorly documented. The VA reported that more than 1.7 million veterans received treatment in a VA mental health specialty program in 2018, and they had 300 VA Vet Centers and 146 VA hospitals available in 2019.109 While they are detailed in the number of available supplies or number of people enrolled in certain programs for screening, diagnosing, and treatment, there are no statistics on return-visits for mental health counseling, satisfaction surveys from veterans in treatment, or commentary from families caring for mentally-ill veterans, among other needed data.110 In a study on the measurement processes of the VA and its use, researchers concluded that poor measurement quality can affect both the level of care offered and any research done in the future meant to alleviate weaknesses in care.111

Preferred Citation: Erin Anderson. “Untreated Mental Illness Among Veterans in the United States.” Ballard Brief. November 2021. www.ballardbrief.org.

Viewpoints published by Ballard Brief are not necessarily endorsed by BYU or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints